The Dublin Lockout and its Effects on Leixlip

advertisement

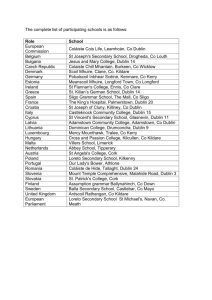

Template cover sheet which must be included at the front of all projects Title of project: The Dublin Lockout:It’s Effects on Leixlip and the Surrounding Area. Name(s) of class / Rian Errity, Jack Murray Hill, Tom McGory, Dan Ryan, Ben group of students / Maloney, Cian O’Sullivan Coffey, Cathal Markey, Anthony individual student O’ Neil, Christopher Udusalu Marcos O’Rourke and Jack submitting the project: Hanley (Captain). School roll number (this should be provided if possible): School address (this must be provided even 18552N Scoil Na Mainistreach Primary School, ` for projects submitted by a Oldtown Road, Celbridge, Co. Kildare group of pupils or an individual pupil): Class teacher’s name Mrs. Catherine Fleming this must be provided even for projects submitted by a group of pupils or an individual pupil): Contact phone number: 0879006578 Contact email address: catherine.fleming@hotmail.com 1 The Dublin Lockout: Its effect on Leixlip and the surrounding area. Introduction. In this essay, we will learn more about the past; what living conditions were like at the time and what effect the huge event of the Lockout of 1913-14 had on Co. Kildare. We are interested in History and chose our topic because it is the 100th anniversary this year of the 1913 Dublin Lockout. Our studies will show us our mistakes in the past, so we can learn from them. As President Michael D. Higgins said, ‘knowledge of history is intrinsic to citizenship’, in other words, if we do not learn from history, it will repeat itself. Conditions in early 20th century Ireland. In the first twenty years of the twentieth century, Dublin was a brutal place to be if you were poor or if you were an unskilled worker on a low wage. The city was populated by many thousands of factory workers, without qualifications, who were competing against each other every day for employment.The owners of the factories were very rich and in the last years of the nineteenth century, Irish workers had nobody to defend or look after them. The conditions many working class people were living in were atrocious. According to a report made to the House of Commons Parliament in London in 1913, about 135,000 people lived in Dublin tenements in areas called ‘slums’. Children from Summerhill Slums circa 1913 2 A witness in this report said that she‘Had never seen in London the utter poverty that was in Dublin.’The 1911 census shows us that infant deaths in Dublin for the years 1901-05 were the highest death rates for babies in Europe. On average, 160 babies died out of every 1,000 that were born in Dublin, compared to London’s 140 out of every 1,000. The tenements were usually large houses in which up to twelve families lived. There was no running water, no electricity and you would have to go outside to a toilet which many of other people in your building used. People living here, in Dublin tenements, were more likely to die or get a serious illness than those living in England or Scotland. T.B. - tuberculosis was everywhere and killed 12,000 people every year in Ireland. The factory workers finally found a man willing to fight for better hours for them, better conditions for them to work in and fair wages. His name was Jim Larkin. He started organising workers into unions. His union was called the I.T.G.W.U. which means the ‘Irish Transport and General Workers Union’ and it started in 1909.His slogan was, ‘A fair day’s work for a fair day’s pay.’ James Connolly, who was born in Scotland of Irish parents, returned to Ireland in 1911 and became a leader in the trade union movement with Jim Larkin. James Connolly also founded the Irish Citizens Army. This group was formed, and armed to protect the workers. The main employer who stood against the trade unions was a man called William Martin Murphy. He owned the Irish Independent and Evening Herald newspapers, the Tramway Company and The Imperial Hotel. Jim Larkin by Ben Moloney, Jan. 2014 Dublin Tram by Jack Hanley Jan.2014 The Dublin Lockout In 1913, William Murphy called a meeting with other employers and an agreement was made that if a worker joined the union he would be sacked. Trouble between Murphy and the ITGWU began in the summer of 1913. He refused to hire members of the ITGWU in July 3 and forbade staff in the Tramways Company from joining the union. On August 21 st Murphy sacked about 100 workers. This was a direct challenge to the ITGWU. Larkin, with the support of his other directors, started a total withdrawal of workers from their employment on 26th August which was the day of the Dublin Horse Show. From August 1913, workers were ‘locked out’ from their jobs. The factory owners employed non union men and women who broke the picket lines. During the lockout, it often became violent between police and strikers and a number of people were killed. The lockout and its effectspread and reachedour locality of Celbridge, Maynooth, Lucan and Leixlip. William Martin Murphy, by Cathal Markey. Jan.2014 The Lockout spreads to our area Of all the small villages mentioned above, Leixlip in the early 20 th century had the most factories with two mills. The large paper mill in Celbridge closed in 1906 leaving many people unemployed. Many of these millworkers travelled to Leixlip to work in the mills there. Tony Maher, a local historian who was born and reared in Leixlip spoke at lengthto our history group in November 2013 about the effect of the lockout on the workers of Wookeys Mill in Leixlip. His own Grandfather Edward Maher, who owned a general store in the Main Street, would also find himself in dire straits due to the effect of the strikes at the local mill. Frederick Wookey was the founder and owner of Wookey’s Flock and Linen Mill. The Wookeys were a wealthy family. The rag and bone man would go from place to place collecting old clothes for a couple of pence or a toy and then would sell the clothing to 4 Wookey’s Mill. Blades were used in the Mill to tear the cotton up into ‘flock’ that was used to stuff mattresses. Workers worked from 6am to 6pm each Monday to Friday with three quarters of an hour break for lunch. The workers also worked on Saturdays from 6am to 2pm. Boys and girls aged 14-16 were paid 3 to 5 shillings per week; women, 4-7 shillings and men 12-16 shillings per week. Edward Maher outside his Leixlip shop circa 1914 One Sunday, in August 1913, Mr. Wookey was walking past the Mall in Leixlip when he saw one of his workers wearing the red hand badge of the I.T.G.W.on his jacket. He ordered the man to remove the badge or he ‘would let him go.’ The worker replied that he would not wear the badge to work but as it was a Sunday he would not remove it. The following day, the same man walked out of the Mill along with thirty five other men who refused to leave the union. Mr. Wookey then told twelve women employees, who were not in any union, that he would have no more work for them if they could not persuade the men to leave the I.T.G.W.U. This was a form of blackmail.At this time, in Leixlip, there were two tenements and the people there used to bring their waste down to the Liffey in metal buckets, in the evenings. They were very poor. According to Tony Maher, parents would not allow their children to swim in the Liffey at Leixlip in case they would get ill with gastroenteritis.People who lost their jobs at the Mill would have been evicted from the tenements. T.B. was in the area and Peamount Sanitorium had opened in 1912. No one wanted the hospital in the area and a mob tried to pull down the scaffolding. The problems with workers at Wookey’s Mill continued. On December 6, The Kildare Observer reported 5 that a number of men and women living in Celbridge and working at Wookeys’ Mill had to be escorted to and from their work by the Celbridge and Leixlip police. Wookey’s Mill in Leixlip circa 1900 When Frederick Wookey sacked the union men at Leixlip, it had an effect on Tony Maher’s Grandfather Edward and his small shop in Leixlip. The men from the mill were out of work and had no money. Their women went to Edward’s grocery shop and were given credit. Mr. Maher gave them food on credit and they promised to give him the money when they were able. More and more people were asking for credit as they were in debt. Many poor people could not pay their bill at Edward Maher’s and so the shop went out of business. This was a result of the Lockout and its effect on Leixlip. The lockout started on the 26 th August and ended on the 18th January 1914. In early January 1914, nearly a thousand dockers went back to work. These members of the union had no money and needed food. This began the end of the lockout. Two days later about 3,000 men signed a document promising never to rejoin the union. In Leixlip eighteen men returned to work at Wookey’s Mill. Some men remained loyal to the union and Frederick Wookey said in the Irish Times that he had no work for them. Immediately after the lockout ended, it looked like the employers had won the battle. The ITGWU may have lost this battle but their ideas and hopes of better conditions for workers passed throughout Ireland. In the long run, the Union really won the battle because Larkin’s idea of unions became popular across Ireland and gradually, more and more unions started to form Conclusion One of the main effects of the Lockout was that it raised awareness of the need to change housing conditions in Dublin. A civic exhibition was held in July 1914. One of the most important things to be discussed was a section on town planning and a competition for a ‘Dublin Development Scheme’. The huge sacrifice of the workers who went on strike finally 6 began to pay off. More attention was now being paid to improving housing, health and sanitary conditions. While doing this essay we learned many things. Ireland is a much richer country now than it was back then with thousands of people living in tenements. During the time of the lockout TB was spreading like wildfire through these tenements with people living so close to each other. With the help of Peamount Hospital, conditions were getting better and the Government began to take a positive interest in the welfare of the Irish people. The Red Hand Badge of the ITGWU by Jack Murray Hill. Jan 2014 We did not know much about the 1913 Lockout before we started. With the coming of World War One and then World War Two, parts of Irish History, like the Lockout, can become forgotten. This was a huge event because of the amount of people that lost their jobs and the families that suffered. It is amazing to think that at the very time we are writing this essay one hundred years ago the Lockout was in action! Now that we have studied about this period in the history of Ireland we hope that as a nation we have learned from our mistakes and this episode of history will not repeat itself. Written by: Rian Errity, Jack Murray Hill, Tom McGrory, Dan Ryan, Ben Moloney, Cian O’Sullivan Coffey, Cathal Markey, Anthony O’Neill, Christopher Udusalu Marcos O’Rourke and Jack Hanley (Captain). Teacher: Mrs. Catherine Fleming. Scoil Na Mainistreach, Oldtown Rd. Celbridge, Co. Kildare. 7 BibLiography Primary Sources. Printed Census of Ireland 1911. www.nationalarchives.ie Newspapers The Kildare Observer 1913. The Irish Times Feb. 1914. Parliamentary Papers. 1913 [Cd 6 909] 42th annual report the local Government Board 1912-1913 H.C. containing a second report on infant and child mortality by the medical officer. Visual and Oral Transcript of interview with Mr. Tony Maher. November 2013 Transcript of interview with Mrs. Ellen Rubotham. January 2014. Internet Sources 1 Co. Kildare Online Electronic History Journal: Lockout 1913. The effect of the great lockout on Co. Kildare by James Durney 2 http://multitext.ucc.ie/d/Dublin_1913Strike_and_Lockout 3 Shackleton Mill/Irish Architectural Archivewww.iarc.ie/exhibitions/Shackleton-mill 4 Shackleton Mills/1913 Dublin Lockout 1913lockout.wordpress.com/shackleton-mill 5 www.Olddublintown.com 6 www.Dublincity.ie 7 Dublin Lockout facts for kids 8 Secondary Sources Newspapers The Irish TimesWednesday,September 11, 2013. ‘Locked Out ’. General Abbott, Maureen. The Story of Celbridge Mill 1712-2010 (Celbridge Community Centre 2010). Cody, Seamus, O’Dowd, John, and Rigney, Peter. The Parliament of Labour, 100 years of the Dublin Council of Trade Unions (Dublin, 1986). Doohan, Tony.A History of Celbridge(Celbridge, 1984). Lyons, F.S. Ireland since the Famine ( London,1977). Monaghan, Lucy. Welcome to Celbridge, Historic Town (Celbridge, 2003). Morrison, George. Revolutionary Ireland, a photographic record (Dublin,2013). Yeates, Pádraig. Lockout Dublin 1913(Dublin,2000). 9