Page - MVHSAParthistory

advertisement

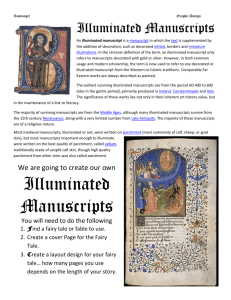

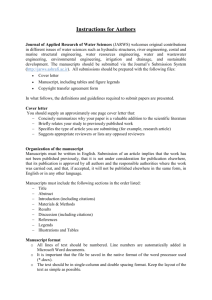

Making Egg Tempera AP Art History Instructor: Erica Ness Making the Binder: 1. Take the Tempera Pigment and add a small amount of water to make a paste in your container. 2. Break open an egg save the yolk. 3. Carefully break open the yolk and pour the contents into your container. 4. Add a teaspoon of water. 5. Stir the mixture with a brush. Assignment: 1. Create an illuminated letter for your name on the 4x6 cardstock. 2. Add interlace designs or try to create an anamorphic design. 3. Paint the design using black, green, and red pigments only. 4. Add gold foil to the surface after it has completely dried. (Next class period) Why use Egg Tempera? Egg tempera is a very long lasting method of painting, in which the color stays very true to its pigment. Why create illuminated Manuscripts? The word manuscript is derived from the Latin words manus (hand) and scriptus, from the verb scribere (to write). Today the term is used to describe any handwritten text. The word illumination comes from the Latin verb illuminare (to light up), which, in this context, describes the glow created by the radiant colors of the illustrations, especially gold and silver. Illumination took the form of decorated letters, borders, and independent painted scenes, called miniatures. Manuscripts were most often written on parchment, a high quality writing support made from the specially prepared skins of calves, sheep, or goats. Although paper could be found in Europe as early as the 14th century, parchment continued to be used for several hundred years in spite of the greater cost involved. Its beautiful texture and translucency, its ability to withstand the wear and tear of daily handling, and its resistance to the dissolving action of acidic inks were among the qualities that made parchment so appealing. The miniatures were painted with a variety of colors, including vermilion and ultramarine blue, and were often decorated with gold leaf. The pigments used in illumination consisted of vegetable, mineral, and animal extracts, which were ground up or soaked out. Vermilion was made from mercury and sulfur, while ultramarine blue, a pigment as expensive as gold, was created by crushing lapis lazuli. Gold leaf was applied to luxury manuscripts in thin sheets; in the later Middle Ages, however, artists substituted gold paint. Makers and Materials The most elaborate and beautiful illumination was devoted to religious works, which, until the rise of universities in the 12th century, were produced in monasteries. European intellectual life in the early Middle Ages was focused mostly in monasteries, many of which made copies of important books and writings (both Christian and classical) and formed their own libraries. In a monastery, the scriptorium was the center for both scholarly activity and the copying of texts. Later, lay artists were often hired to collaborate with monastic scribes. Monastic scriptoria survived throughout the Middle Ages, but by the 12th century, scribes and illuminators were increasingly laymen who made their living by supplying fine manuscripts to noblemen, the new middle class, and the emerging universities in cities such as Paris, Bologna, and Oxford. Some religious communities also began copying manuscripts on a commercial basis. By the 12th century, the production of a luxurious illuminated manuscript had been divided among four distinct craftsmen: the parchment maker, the scribe, the illuminator, and the bookbinder. Each was required to belong to a guild that had specific rules governing both the quality of work and the rights of its membership. The guilds also set standards and procedures for training apprentices. Frequently Page 1 the guild maintained a monopoly over the rights of manufacture as well as the sale and price of goods. An independent middleman, usually an individual illuminator or a scribe, was responsible for coordinating the efforts of the four workshops involved in each commission. The parchment maker prepared the animal skins used to make the leaves of a manuscript. The skins were soaked in a bath of lime to remove the hair. They were then stretched, scraped down, and rubbed with pumice. The final steps were to whiten the skins with chalk and cut them to size. The scribe wrote the manuscript's text by hand. Scribes usually made their own quills and ink, just as illuminators prepared their pigments. To make the text appear in a consistent format throughout the manuscript, the scribe drew ruling lines on each page to establish the margins and the spaces between the lines. The illuminator provided the manuscript's painted decoration. Illuminators and painters of large, freestanding panels were often members of the same guild and equally respected as artists. The number and variety of illumination in a single luxury manuscript often required the collaboration of several craftsmen, and the master of a workshop would often assign some miniatures, borders, and initials to assistants. The bookbinder provided a binding to protect the manuscript, which held the leaves together and kept them from curling. Metal clasps or ties of leather or fabric were used to keep the manuscript closed. Bindings were sometimes embellished with paint or enamel or with designs stamped with metal tools; the most precious manuscripts were adorned with metalwork and jewels. Brief History of Illuminated Manuscripts The artistic aims of medieval painters often found their purest expression in manuscript illumination, one of the primary media of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Illuminated manuscripts contain most of the finest surviving examples of medieval painting and therefore constitute the most complete record of its development. The art of illumination flourished in the early centuries of Christianity when the manuscript codex, or book, gradually replaced the papyrus roll of antiquity as the vehicle for the written word. Because of the close connection of medieval Catholicism with the handwritten book, the texts of many manuscripts were embellished to enrich public or private religious experience. By the end of the medieval era, as Europe became wealthier and more worldly, a great variety of texts, both religious and secular, came to be illuminated. Insular Manuscripts (seventh to eighth century) The origins of Western European illumination was the Christian British Isles. The Insular miniatures of seventhcentury Ireland developed the late antique practice of enlarging the first letter or initial at the beginning of a text into an entire page—known as a carpet page—which was covered with abstract designs. The tradition of using elaborately decorated text pages in books of Gospels and other liturgical manuscripts flourished into the Ottonian and Romanesque periods. Byzantine Manuscripts (sixth to 15th century) In the Byzantine Empire, another tradition of manuscript illumination emerged. The most influential characteristics of Byzantine manuscript painting were the abundant use of precious metals, especially gold; the choice of bright colors; and the use of empty space, often filled with gold leaf, as background. Byzantine illumination was frequently devoted to narrating biblical stories. Styles of depicting the human figure varied in Byzantine art over the centuries. Carolingian Manuscripts (eighth to ninth century) The Emperor Charlemagne (reigned 800–814), whose empire extended from northern Germany to Italy, encouraged artists to emulate the naturalism of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Using Byzantine models that reflected classical art, Carolingian illuminators combined this naturalism with an exhilarating, nervous brushwork. Ottonian Manuscripts (10th to 11th century) In the mid-10th century, a line of German kings including Otto I, Otto II, and Otto III began to commission manuscripts that, as in the Carolingian tradition, were to be a visual manifestation of imperial power. The Ottonians also borrowed heavily from Byzantine art, using a narrative style that expresses the gravity and simplicity of Byzantine icons. The Making Egg Tempera AP Art History Instructor: Erica Ness volumes of the figures and the spatial relationships are reduced to luminously colored patterns. The figures have large, expressive eyes and long, gesturing hands—motifs that are also derived from Byzantine art. Romanesque Manuscripts (11th to 12th century) Romanesque art was international in character, borrowing from both Insular and Byzantine art. The Insular focus on initials became the central element in Romanesque illumination, and the historiated initial, which contains an illustrative scene, was derived from the Byzantine interest in narrative. Patterned backgrounds along with abstract drapery were extremely popular. Gothic Manuscripts (13th to 15th century) By the end of the 12th century, Parisian artisans had developed a new style of illumination characterized by sinuous figures, vivid narratives, and the lavish use of gold leaf. During the 13th century the English and German schools developed Gothic styles as well. French illuminators occasionally adopted the visual conventions of other art forms, such as stained glass windows, in order to narrate stories and teach church doctrine visually. International Style (first half of the 15th century) The International Style reached its height in the early 15th century at the ducal courts of Europe. At this time Jean, duc de Berry, one of the great patrons of this period, commissioned the famous Très Riches Heures. His illuminators, the Limbourg brothers, were among the great exemplars of a new naturalism, elegance, and fascination with landscape that quickly spread throughout Europe. The courtly manner of this style circa 1400–1420, is reflected in its bright colors, soft modeling, and delicate contours. The Renaissance (15th to 16th century) The Renaissance in both Northern and Southern Europe was the last great era of the handwritten and illuminated book. Expanding literacy provided a stimulus for affluent middle-class patrons both to commission manuscripts and to purchase those made for the open market in towns and cities all over the continent. An illuminated private devotional prayer book, for example, became a symbol of its owner's status and taste. Renaissance illuminators also produced many secular works. The study of antiquity in Italy gave rise to beautifully illuminated humanistic texts. Although Gutenberg's invention of the printing press in 1452 was not immediately successful, soon he and other printers throughout Europe were vying with scribes to meet the increased demand for books. Imitating the manuscript tradition, early printed books were often illuminated, and occasionally achieved the decorative splendor of luxury books. Eventually, however, the use of woodcuts and metal engravings replaced illuminated decoration in printed books. Within the next hundred years, the advent of the illustrated printed book led to the demise of a glorious tradition that had flourished in Europe for 10 centuries. Page 3