Mayan Religion

advertisement

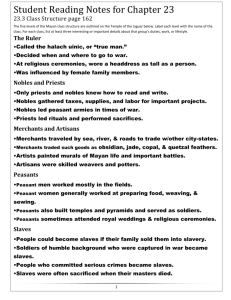

What was the Maya Religion? The Maya are a native Mesoamerican people who developed one of the most sophisticated cultures in the Western Hemisphere before the arrival of the Spanish. Mayan religion was characterized by the worship of nature gods (especially the gods of sun, rain and corn), a priestly class, the importance of astronomy and astrology, rituals of human sacrifice, and the building of elaborate pyramidical temples. The Maya worshipped a pantheon of nature gods, each of which had both a benevolent side and a malevolent side. The most important deity was the supreme god Itzamná, the creator god, the god of the fire and god of the hearth. Another important Mayan god was Kukulcán, the Feathered Serpent, who appears on many temples and was later adopted by the Toltecs and Aztecs as Quetzalcoatl. Also important was Chac, a hooked-nose god of rain and lightning. A third god that frequently appears in Mayan art is Bolon Tzacab, who is depicted with a branching nose and is often held like a scepter in rulers' hands. He is thought to have functioned as a god of royal descent. The Maya were obsessed with time; to understand and predict various cycles of time allowed them to adapt to and best make use of their natural world. Mayan cosmology had it that the world had been created five times and destroyed four times. On a more temporal scale, the various days of the year were considered appropriate to specific activities, while some were entirely unlucky. Practices The Maya practiced a form of divination that centered on their elaborate calendar system and extensive knowledge of astronomy. It was the job of the priests to discern lucky days from unlucky ones, and advising the rulers on the best days to plant, harvest, wage war, etc. They were especially interested in the movements of the planet Venus — the Maya rulers scheduled wars to coordinate with its rise in the heavens. The Mayan calendar was very advanced, and consisted of a solar year of 365 days. It was divided into 18 months of 20 days each, followed by a five-day period that was highly unlucky. There was also a 260-day sacred year (tzolkin), divided into days named by the combination of 13 numbers and 20 names. For longer periods, the Maya identified an elaborate system of periods and cycles of various lengths. In ascending order, these were: kin (day); uinal (20 days); tun (18 uinals/360 days); katun (20 tuns/7,200 days); baktunbaktun (20 katuns/144,000 days), and so on, with the highest cycle being the alautun (23,040,000,000 days). These units were used in the Maya Long Count, which calculated the time elapsed from a zero date set at 3114 BC. In the Postclassical Period, the method of notation was somewhat simplified, and the Long Count katuns end with the name Ahau (Lord), combined with one of 13 numerals; and their names form a Katun Round of 13 katuns. Until the mid-20th century, scholars believed the Maya to be a peaceful, stargazing people, fully absorbed in their religion and astronomy and not violent like their neighboring civilizations to the north. This was based on the Maya's impressive culture and scientific discoveries and a very limited translation of their written texts. But since then, nearly all of the Mayan hieroglyphic writings have been deciphered, and a much different picture has emerged. The texts record that the Mayan rulers waged war on rival Mayan cities, took their rulers captive, then tortured them and ritually sacrificed them to the gods. In fact, human sacrifice seems to have been a central Mayan religious practice. It was believed to encourage fertility, demonstrate piety, and propitiate the gods. The Mayan gods were thought to be nourished by human blood, and ritual bloodletting was seen as the only means of making contact with them. The Maya believed that if they neglected these rituals, cosmic disorder and chaos would result. At important ceremonies, the sacrificial victim was held down at the top of a pyramid or raised platform while a priest made an incision below the rib cage and ripped out the heart with his hands. The heart was then burned in order to nourish the gods. It was not only the captives who suffered for the sake of the gods: the Mayan aristocracy themselves, as mediators between the gods and their people, underwent ritual bloodletting and self-torture. The higher one's position, the more blood was expected. Blood was drawn by jabbing spines through the ear or penis, or by drawing a thorn-studded cord through the tongue; it was then spattered on paper or otherwise collected as an offering to the gods. Other Mayan religious rituals included dancing, competition, ball games, dramatic performances, and prayer. From: http://www.religionfacts.com/mayan_religion/index.htm