“Mattered”: A Quantitative Economic History of the Republic of Ragusa

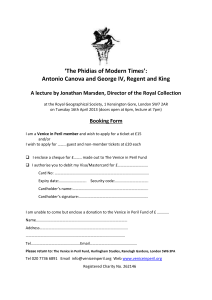

advertisement

INSTITUTIONS ALWAYS “MATTERED”

Quantitative Evidence of Favorable Institutions in

The (forgotten) Republic of Ragusa ,1000-1800

Oleh Havrylyshyn and Nora Srzentic.

1

Draft.1. CPE (17,700 words)

INSTITUTIONS ALWAYS “MATTERED”

Quantitative Evidence of Favorable Institutions in

The (forgotten) Republic of Ragusa ,1000-1800

{Author deleted}

“Among permanent state institutions [activities? au.}

the primary is a responsibility to preserve justice and

order among wholesale and retail merchants , and

customers, irrespective of whether they are foreigners

or citizens”

Filip de Diversis, Ragusa : 1440 1

1

As cited by Stipetic (2000); he translates t the Latin ???? as institutions which may be a stretch , though the spirit

is right. Filip de Diveris was an Italian teacher in Ragusa’s gymnasium who wrote in 1440 the book Situs

Aedificiorum,Poilitiae et Laudabilim Consuetudinum Inclytae Civitatiis Ragusii.

2

I.

INTRODUCTION AND MOTIVATION

The vast literature of the New Institutional Economics (NIE) relies mostly on historical

examples of Western Europe and its colonies, with only a few references to Venice and

other Northern Italian City-states. But an excellent historical example of good

institutions, the tiny Republic of Ragusa has been overlooked by economists.. Over the

period 1300-1800, Ragusa (today Dubrovnik), despite its small population never

exceeding 90,000 , with a mere 1,100 sq.km of very small infertile territory that was

difficult to defend, achieved a remarkable degree of economic prosperity and

disproportionate importance in Mediterranean trade. Lane’s (1972 ) history of Venice

frequently notes Ragusa was considered its main rival in maritime trade.Fernand

Braudel in several places refers to this ‘jewel of the Adriatic.” Shakespeare and others

glorify it implicitly by the frequent use of the term “Argosy “ , a fast ship with rich cargo.. 2

Most historians attribute its success not to mere luck of location, but good governance,

an atypically benevolent rule providing many basic needs of commoners, institutions

favorable to commerce, upward mobility, and meaningful rule-of-law.3

This work on Ragusa is motivated by three considerations. First , most historical

evidence of the NIE paradigm ,that “institutions matter for growth “ , is based on 1719th c. Europe and its colonies , with surprisingly little attention to the earlier economic

growth spurts in Northern Italy, despite its being known as “the Cradle of Capitalism .”

While some work on Venice exists , we wish to add to the NIE literature an example of

a very small but highly successful economy , Ragusa. Secondly, while both Croatian4

and other historians have produced a considerable literature on Dubrovnik , very few

economists have written about it, and the analysis is sorely lacking in quantitative

evidence . We thus propose to compile as much data as possible to retell its story.

Finally, the economic histories that do analyse the role of institutions in earlier periods,

are not yet linked to the most recent developments of the Institutional Paradigm and the

various categories used for quantifying institutional quality as in the many indicators or

scores reported in the World Bank’s two main publications : The World Governance

.Both Oxford and Webster’s clearly define Shakespeare’s “argosies with portly sails” in The merchant of Venice

as ships of Ragusa.,Though he used poetic license to imply they were Venetian.,contemporaries knew better.

3

This paper might be considered a mirror-image of the approach in Kuran (2011) on the Ottoman empire. He starts

with the same principle we do -”when communities differ in their economic accomplishments, the reason often lies

in the legal regimes under which they conduct business”- though his purpose is to show that inadequate institutions

explain why the Ottoman-Muslim Empire fell behind in the Middle Ages.

4

Indeed , Yugoslav writers earlier as well.

2

3

Indicators (WGI ) and the Doing Business Report (EDB). We present data on Ragusan

institutions that are analogous to now-common categories.

Our aims in this paper is to make three contributions to the literature. . First we will

briefly test and confirm the conventional histroian’s views on the prosperity and

importance of Ragusa with quantitative proxies of economic activity . Second, using the

concepts of today’s NIE, we will provide some quantitative measures of highquality institutions of governance, Rule-of –Law (ROL),contract enforcement,, and social

measures. Based on these we then conclude Ragusa provides a very early historical

example of how institutions “ matter “ for growth. We do not claim Ragusa was unique

in that regard, as several Northern Italian city-states followed similar development

models,5 but it is nevertheless an excellent example of how good institutions contribute

to growth

. The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Sec. II summarizes the aspects of the

NIE relevant to this paper., while Sec. III briefly reviews the history of the republic of

Ragusa., including a quantification of its economic evolution and high degree of

prosperity in its “Golden years “6 , the 15th -17th centuries. Next, Sec. IV discusses

argues that the main explanation of its success was good institutions, with several

quantitative measures of the high quality of its institutions supplemented with more

traditional qualitative assessments. Sec. V draws the main conclusions and points to

potential future research.

Two clarifications are in order. First, we generally use the Latin name Ragusa, as

Dubrovnik was then known. Second, we do not claim Ragusa was the only example of a

prosperous city-state with sensible economic policies and good institutions ;indeed we

accept the view of some scholars that a lot of Ragusa’s wise policy emulated –but

perhaps Improved upon – those of its main overlord and rival , Venice.. This paper begs

the question “ how exactly was Ragusa better than Venice or other Dalmatian portcities”, a more difficult analysis left to future research.

II.

RELEVANCE OF THE NEW INSTITUTIONAL ECONOMICS (NIE)7

Perhaps the best definition of economic institutions remains that of North (1994, pp359360) : “Institutions form the incentive structure of a society, and the political and

economic institutions, in consequence, are the underlying determinants of economic

performance. Time as it relates to economic and societal change is the dimension in

which the learning process of human beings shapes the way institutions evolve.”.

Indeed this definition also states succinctly the central thesis of the NIE, that institutions

matter for growth. While North and Weingast pioneered this paradigm as early as

their 1973 book, it did not permeate into standard growth and development economics

until 20 years later when numerous econometric studies of growth began to include

Venice is given some attention here , as Ragusa’s model, nemesis, and main competitor in trade.

Sec.III is based on the extensive analysis in (2013 ) publication by author –to be given)

7

This section is based on an extensive survey of the NIE in Ch. 2 of a forthcoming book by the authors .

5

6

4

variables “measuring “ the quality of institutions.. Doing so was facilitated by the vast

efforts to develop numerical indicators of institutions: those of the World Bank stand out

but many others now exist –indeed some writers consider there is a surfeit of

measures.. many are altogether skeptical of such measures. As often happens in a

paradigm’s evolution,theory comes first, they are applied empirically, and the literature

then returns to revisit the theories, A key contributions to the latter is the survey of

Acemoglu , Johnson and Robinson (2005 ), a central finding of which is that despite the

uncertainty about measurement and many econometric disputes, on balance the

literature shows that “institutions matter”. Our paper’s title and content is launched

from this , arguing that institutions always “mattered”, even much farther back in history

than the literatures’ general coverage from about 18th c. Europe and its colonies.

Today one might summarize the NIE literature under five main issue or debates:

1. is there a metric for measuring institutions quantitatively ?

2. do institutions truly play a significant role in explaining growth?

3. how large is this effect compared to traditional neo-classical determinants?

4. are some institutions more important than other

5. how do institutions come about ?endogenously as per the Coase theorem of

efficient-markets , or by the exogenous actions of state authorities?

Before addressing these we give a short sketch of the main theoretical tenets of the

NIE, that is how institutions affect growth .As already noted the argument is first laid out

in the pioneering works of Douglass North, his co-authors Thomas, and Weingast,

and somewhat independently those of Oliver Williamson( 1985 ). These pioneers pay

tribute to earlier theoretical building blocks for the NIE ,like Coase (1937 , 1960 ) on

efficient marketswhich develop endogenously institutions protecting property rights, and

Olson (1965,1993) ), on state authorities maximizing their “income “ (=taxes ) byt

protecting such rights and motivating economic growth.. Somewhat forgotten ,North

also relied on the American ( the “old ? “ )School of Institutionalism ( Veblen,

5

Commons, Berle ) which saw institutions-qua-entities ,-i.e. public and private agencieswhose rules and actions affected the behavior of economic agents.. North’s wove all

this into a whole-cloth comprising

theoretical thesis:

a new paradigm with a focused and clear

: to understand economic prosperity one needs to study which

institutions best promote it.

The NIE focuses on the mechanisms that support and enforce property rights in a way

which facilitates rather than hinder the pursuit of economic activity. Unlike the earlier

American Institutionalism of the late 19th , early 20th century , NIE is not a critique of

orthodox neo-classical economics or its utility and profit maximization axioms. Indeed

institutions are considered a hand-maiden to the market -a view nicely reflected in the

now-common term “ market –enhancing- institutions .”i Compared to the earlier

Institutionalism a first insight of North was to define institutions not as entities ,as

organizations of society like governments, courts, enterprises - but as the rules-of-the

game by which actors in the market must play. Good institutions were those that

allowed free enterprise, secured property rights, and enforced contracts, but also put

constraints on monopolistic, non-competitive activity, His second important insight

was to distinguish formal institutions ( laws , regulations , judicial procedures, diktats )

from informal ones ( habits, mores, ethical norms). The reason for such a distinction

was that laws can be subverted or unequally implemented , and what determines the

quality of institutions in the end is how the informal implementation of formal laws

affects the quality of the entire structure of institutions. This is not to say formal laws are

irrelevant, rather that in the notional basic equation of the North model with the

dependent variable “economic performance” , the independent variable “institutions “

6

has to be properly defined as the combined effect of both formal and informal

components. This is far from easy to do in practice and has spawned the first key

debate of the NIE: can institutions be measured .

Some early but very broad measures like Polity IV with its democracy scores were

used by analysts at first. More concrete economic-institutions began to be given

numerical value

by The Heritage Foundation , The World Bank, Transparency

International and so on. These were based on a combination of “expert” judgments

and surveys of economic agents’ views on such things as : how easy is it to deal with

tax-authorities; how easy is it to open , conduct , or close a business; how effective, is

governance; how much corruption is there; how quick and fair was the rule-of-law.

Most such measure’s were criticized as being subjective unlike the objective metrics of

other economic variables such as quantity of items, value of production, sales , exports.

The counter-argument noted North’s warnings that it was not formal laws that mattered ,

but their practical application, and who better to judge this than the objects of

implementation of rules?

We cannot of course obtain for Ragusa t systematic historical judgments of this sort,

but often a consensus exists in historical writings , contemporaneous and recent , about

the nature of governance in a state. Surprisingly, we are able to get specific , albeit

limited , objective measures analogous to todays’ “Ease of Doing Business “ measures

( World Bank, Doing Business Annual Reports ), like the amount of time to settle

bankruptcy /contract disputes; these are reported in Sec. IV..

7

Debates 2

and 3 have been addressed by numerous empirical studies using the

above quantitative indicators. Both Williamson (2000) and AJR 2005 ) conclude that

there exists a wide consensus : institutions do matter. There is also agreement the

effect of institutions is important enough that traditional factor input variables alone do

not tell the full story. Indeed , some like Rodrik , Subramanian and Trebbi ( 2004)

contend that in the long-run institutions “rule “, that is they are the sole explanation of

success needed.. It is beyond our scope to go into this debate, but our analysis of

Ragusa , though necessarily not done as econometrics, strongly suggests that even in

the long run, fiscal and monetary prudence

sum, the

view

that

were important contributors to growth.In

market-enhancing quality of institutions matters for growth has

become widely accepted, almost to the point of an axiomatic status.

The fourth debate , on the relative importance of different institutions is very much open

and the subject of current research.. Haggard and Tiede(2011), show that for

developing countries in particular, institutions underpinning political and social stability

are m opre importan than those protecting property rights. Havrylyshyn ( 2008)

suggests that for transition economies , the most important institutions for early

recovery were basic price , market , and external liberalization were initialy more

important than good legal or financial institutions.. Understandably , soft historical

data from the 15th c. are hardly good enough to compare the importance of different

institutions, so we do not address this debate.

8

On the fifth debates, how institutions develop, .AJR (2005 ) end their review by

suggesting future work needs to concentrate on asking what determines the quality of

institutions , and why they are ”better “ in some countries and some periods than in

others. At the start, North and colleagues posited a Coasian efficient-markets view

that demand by merchants rather than exogenous provision of good laws by mostlymonarchical governments were the source of good institutions AJR (2005) take a

somewhat more eclectic view, that both exogenous actions of governments, and

endogenous developments by merchants, business people do create institutions—a

view held by many “ liberal” ( in the American sense ) economists . Of equal interest is

the debate with historians, many of whom increasingly question North’s interpretation

that mediaeval kingdoms and courts were too rapacious, too little developed, too biased

to provide market –friendly institutions and ROL. Thus Ogilvie (2011) provides

extensive evidence of governments in fact being the main developers of commercial

courts, and clear evidence that merchants, guild-members, citizens and foreigners,

relied heavily on government courts. Our finding s for Ragusa are that the bulk of

rules and legal procedures did indeed come from governments. However, given

Ragusa’s very small size and the fact that it ruling class of “nobles” were almost

universally involved in some commerce, this leaves open the question whether the

genesis of institutions was exogenous or endogenous.

III.

REVIEW OF RAGUSA’S HISTORY 1100-1800

III.1. Timeline of Historical-Political Development

9

The first “records [of] Dubrovnik’s arsenals (shipyards) date from the year 782,”8 which

is broadly consistent with the popular founding story/myth

as a significant settlement

by Greek-Roman

9

that Ragusa was founded

denizens fleeing from the 639 Avar

invasions of ancient Epidaurus (Cavtat)..Its rise was quick: even informal views such

as Wikipedia’s , that “from the 11th century Ragusa emerged as an important maritime

and mercantile city”,10 are widely shared by contemporary and modern writers. In 1153

Andalusian geographer Idrisi wrote: “Ragusa was a large maritime town whose

population were hard-working craftsmen and [it ] possessed a large fleet which traveled

to different parts.” (Carter, 1972, p.74). In 1553 .Giustiniani noted its nobles had

fortunes far in excess of other Dalmatian cities, and comparable to the Venetian elite,

with “many individuals having [wealth] of 100.000 ducats and more“11.

While most historians describe Ragusa an independent Republic with relatively

democratic procedures, relatively benevolent attitudes to commoners,,12 in fact de jure

it was usually in a suzerainty, tributary, or protectorate status under one or another of

the larger powers. Nevertheless de facto it was

quite autonomous in its internal

governance and external commerce for the better part of a millennium, justifying its

motto LIBERTAS13. Just how much more democratic and benevolent it was than others

is debatable, and we elaborate on this in Sec, IV.. Historians vary slightly in classifying

the main periods of Ragusa’s history a broad consensus gives the following:

8 Nicetic (2002, p.11)

9

As all early history, there is a mixture of myth and fact, which Carter (1972), and Stuard (1992). inter alia try to

sort out. Note Epidaurus was a mere 15-20 km. south of Ragusa.

10

http://en.wikipedia .org/wiki/Maritime_Republics; accessed 8/1/2011

11 Krekic (1997, p.193) Well-paid sailors could earn a few hundred ducats yearly, captains 3-4 times.

12 Author’s (2013) publication discusses these claims.

13 .Kuncevic (2010) elaborates on the reality and myth of LIBERTAS.

10

The Byzantine period about 8th/9th century to 1204: Ragusa was mostly under

Constantinople’s suzerainty, with periods of submission to Venice, Hungarian

kings, Normans in Naples, and even some years of independence. But it enjoyed

considerable autonomy and enough neutrality to have trading rights with all sides.

The Venetian period, 1204 to 1358: Ragusa accepts formal submission to Venice,

a Republic at least 10 times larger, with a vastly more powerful naval fleet.

Venetian Counts were appointed formal heads of state, tribute was paid and in

war it contributed one vessel per thirty Venetian ones In return it retained internal

autonomy and importantly, with Venetian “protection “ was allowed the valuable

privilege of trade intermediation between the Balkans and Venice. Paradoxically

during this period Ragusa begins to develop a maritime prowess which eventually

leads to its becoming a major rival of Venice in Mediterranean trade.

Hungarian suzerainty, 1358-1526: Under the 1358 Treaty of Zadar Ragusa

becomes a dependency of Ludovik I after he drives Venetians from most of the

Dalmatian coast. But the Hungarian kings were content with inland superiority over

Venice and not interested in Mediterranean trade, allowing full trading rights to

Ragusa-under its “protection” allowing it to sign separate treaties.

The Ottoman period: 1526-1684. The Hungarian defeat at Mohacs formally puts

Ragusa in a protectorate status under The Porte., though given the preceding

loose control of Hungary, relations with the Ottomans began much earlier. The

first treaty was in 1392, with expansion of its terms in 1397 to fully free-trade in

Ottoman regions, and yet another treaty in 1459 after Turkish occupation of

Serbia. The well-remembered defeat of Serb forces at Kosovo Polje in 1389, and

Ottoman’s crowning achievement with the fall of Constantinople in 1453, clearly

signaled the need of Ragusa to deal directly with the Porte despite its formal

dependency on Hungary.

The Austrian period, 1684-1806 was a faint echo of the earlier periods. Ragusa

retained considerable autonomy particularly for Balkan trade ,however its relative

( but not absolute ! ) economic importance began to decline in the 17 th c. With its

economic strength sapped by the overall decline of the eastern Mediterranean..

diplomacy was decreasingly effective. Indeed some interpretations suggest

Austrians did not seek firmer authority over Ragusa ,now generally called

Dubrovnik, precisely because its relative commercial importance was much

reduced.14,

French occupation in 1806 ends independence of Dubrovnik, not just de facto, but

de jure. During the Austrian-French wars too weak to use its earlier diplomatic

efforts to retain neutrality, surrendered to overwhelming French forces and lost

Republic status. With Napoleon’s defeat the 1815 Congress of Vienna returned

14 “Relative” is the operative word here: In Sec III we show data suggesting absolute level of economic activity might have been still very large .

11

Austrian control over Dalmatia, but not Dubrovnik’s city-state privileges15. It becme

merely a city in the Dalmatian province. By 1900 railroads had further undermined

Dubrovnik’s advantages.

The Modern Pariod : 1918-present. As the Versailles Trety created the SouthSlav ( Yugoslav) Kingdom , Dubrovnik’s importance continued to fall , with Rujkeka

and Split becoming industrial and poert cities of far greater importance and size.Its

former maritime fame disappeared , but it gradually grew into an important tourist

destination,> the crowning achievement was a designation as a UNESCO World

Heritage site in 1979.After the Yugoslav wars ended and calm returned by the late

nineties, a new worldwide fame took over: Dubrovnik becomes a standard stop in

Eastern Mediterranean cruises. While few people , even erudite ones, know the

name “Ragusa”, .the ubiquitous photo of its majestic city-walls in brochures and

TV commercials now means almost everyone will say “ sure I heard of

Dubrovnik”!

III.2. Economic Periodicity

Virtually all histories of Ragusa are structured on historical political models, with period

classifications dependent on key events: wars, victories, treaties, regime changes.

Given this paper’s focus on economic evolution we propose a new classification based

on the nature of the economic development. This is shown in Table 1 with approximate

dates. And a brief description of the main economic activity driving growth. 16 The paper

will focus on the Silver and Golden-Years period , the apogee of Ragusa’s economic

achievements since for the preceding Foundation Period quantitative indicators are

virtually non-existent, while the later periods are of much less analytical interest. As by-t

hen-Dubrovnik becomes a minor entity in the region.

TABLE 1. CLASSIFICATION OF ECONOMIC PERIODS

15This lends truth to the assertion by Luetic (1969, p107) : “the French occupation…overthrew the 1,000 year historical thread of Dubrovnik’s sea-based livelihood, and destroyed

the significance of Dubrovnik as a world-class maritime power.”

16

This is explained in fuller detail in Author (2012)

12

Economic period

Years

(approx.)

Foundational Period

To 1250

Subsistence agric, fishing, short-distance maritime

trade,small-ship building , Balkan trade(-including slaves)

Silver Period

1250-1400

All above continues; plus with strong growth in hinterland

trade of Balkan raw materials . This period saw a boom in

trade of silver and other minerals, to Northern Italy,as well

as gradual increase in long-distance entrepot trade

beyond Adriatic

Golden Years

1400—

1575/1600

All above plus : significant increase of long-distance

Maritime trade between Levant and Europe , initially

through Venice , Ancona, later direct.. Some historians

suggest maritime trade more important than Balkan trade.

1575/1600

Levant trade gradually lost to new West European

to- 1750

Competitors( Portugal. Spain, Netherlands , Englandreact with efforts to trade more directly in West

Mediterranean and even Atlantic

Cape Hope Route:

Gradual Decline of

Ragusa

Revival Interlude

Post-Independence

Nature of Economic Activity

1750-1806

Balkan trade continues, maritime trade to Ponent and

Atlantic expands. As new naval powers in West dominate ,

Ragusa turns to new activity: building or hiring-out ships

and sailors to Spain, Netherlands England., etc.

1806-1900

Decline sharpens, maritime advantages undermined by

railroad sin late-19th.c. However small beginning of

tourism-economy, the eventual new source of prosperity.

Source: Authors’ classification

It is nevertheless useful to give some idea of the relative economic dynamism of

different periods; we do this in Figure 1, which shows for each period the absolute

numbers of monumental building constructed in that period, the share of the total in the

13

millennium , and a crude index of “building intensity” (=number of buildings per 100

years) as a proxy of economic dynamism17.

Figure 1: Principal buildings in Ragusa by period 9th-19th century

Sources: Authors’ calculation using Chart XIII Carter (1972).

Taking this at face value the numbers

seem to confirm the conventional view that the

Golden Years ( about 1450-1600) were indeed the peak period of economic prosperity

and growth., with the largest number of buildings, the highest share by period and the

highest per century intensity. The foundational period shows a start but still very

modest. However, perhaps most interesting in this table is how large a share of the

major structures were put in place in the Silver period, with an intensity of building far

greater than the late periods and second only to the Golden Years. This is interesting

because it is largely ignored and unrecognized by historians—with the possible

exception of Stuard ( 1975-76). Admittedly this is a very crude proxy for economic

17 This may underestimate the number in later periods since it shows only buildings within the city walls, and territorial expansion over time likely meant more major building

projects outside as well.

14

dynamism “ it does not adjust for size or complexity, elegance of monumental buildings,

and perhaps underestimates

numbers in later centuries as

Carter’s list excludes

buildings outside the old city walls. But with the exception of the new conclusion about

the Silver period , it is very consistent with the conventional history of Ragusa. We go

on to provide some quantitative evidence on the degree of Ragusan prosperity and

comparison with Venice and others states.

III.3. Quantitative Evidence of Economic Growth

Before the11th. c .the economy was very simple, largely self-sufficient, based on

fishing, some agriculture, building of small craft. This was nevertheless an important

period in building the foundations of future prosperity and dominance in Dalmatia. One

sees a gradual movement into nearby coastal entrepot trade, as well as intermediation

between the Balkan hinterland and thriving Italian cities like Venice, Florence, Bari,

Ancona. With the first shipyard already in 782 -within a century of its founding- Ragusa

was clearly already moving into maritime activities. Early evidence

of its shipping

prowess notes that in 783 Charlemagne hired Ragusean ships to transport Croatian and

Serbian mercenaries across the Adriatic in his campaign to drive Saracens out of

Apulia18.Another indicator of an early economic development was its ability to withstand

for 15 months the 866 Saracen siege until Byzantine ships lifted it -indirect but strong

evidence that: 1) Ragusa was worth seizing, and 2) defenses were already quite

strong. The literature also contains accounts of caravan trade between Balkans and

Italy through Ragusa involving

cattle, leather, wood/lumber, honey, wax, traded for

textiles, household goods, metal products, and various luxuries .

18Carter (1972, p.53), based on writing of the Byzantine Porphyrogenitos-though Carter warns in many places such early writings probably had many confusions.

15

In subsequent periods , both Balkan trade and maritime trade increased over time,

though the relative importance varied. In the “Silver period, starting gradually about

1250 minerals trade surged as old Roman mines in the hinterland re-opened ( and new

ones opened ):Srebrenica, Novo Brdo, Rudnik. The main item was silver, but gold, lead,

iron, also played a role.19 Stuard (1975-76) describes how Ragusa quickly became a

principal conduit meeting the high demand for silver in Europe; Stipetic (2000, p.26)

states Balkan silver production about 1400 was almost one-third of European totals, and

of this almost one half (i.e about 16% of European total) was exported through Ragusa.

Required sales to the Ragusa mint generated considerable seigniorage profits for the

state treasury. Significantly, the earlier Balkan trade in raw materials also continued.

.An important parallel development was a rapid expansion of ship ping capacity as

Ragusean elites recognized that greater benefit would come from Balkan-Italian trade

of the goods were transported in their ships. Already in the 14th. century one finds

discussion of

a burgeoning maritime trade rivalry with Venice, Ragusa’s nominal

suzerainty. We show in Figs. 2,3,, some quantitative evidence of growth in the two

central economic periods. Fig. 2 shows for the period 1300-1500 the first surge in

population as well as the expansion of territory – the latter largely based on purchases

from neighboring Bosnian or Serbian rulers. True, for population, Vekaric (1998) argues

much of the expansion prior to 1500 was due to the push of Balkan-Slavic refugees

fleeing the advance of Ottomans. However, economic attraction pull factors

also

played a role:. There is little doubt the level, of per capita income in Ragusa was well

above that of the immediate Croatian hinterland (Stipetic 2004). There is also a steady

19 Often the location names define the mineral: e.g. Srebrenica for silver, Olovo for lead, but Rudnik simply mine.

16

increase in the commercial fleet size, with a probable doubling from about 22 longdistance ships in 1300 to 40 by 1325 and even larger increase in Tonnage ( Fig. 3.).

.20

Figure 2: Population and area: Ragusa 1300-1800

Source: Appendix tables in :Author (2013

The data confirm the dynamism of the Silver Period., but also

traditional view of scholars that

Ragusean

make clear that the

the Golden Years were indeed the apogee of

prosperity: population reaches its maximum in 1500 of about 90,000,

though tonnage continues to expand until 1575. The main basis of prosperity in this

period becomes maritime trade intermediation, not only throughout the Adriatic but

increasingly with the Levant territories under Ottoman rule bringing goods from the Far

East such as spices, silk, oriental perfumes, grains, and other raw materials. But the

20

The charts are taken from -----authors (2013) to be provided -. It is not unusual to use shipping tonnage as a

proxy for economic activity and most certainly justified for a tiny state whose major activity may have been

shipping. In the cited paper , the correlation coefficient between tonnage and GDP for the years the later is available

is 0.53—with population it is 0.88

17

structure of trade with the Balkans remained the same, and there is little doubt that the

strong

preceding

experience

as

well

as

the

extensive

Ragusa/Dubrovnik, provided a critical comparative advantage.

slavicization

of

It is a tribute to the

governing elites of Ragusa- both nobility and merchants- that early on they leveraged

their economy on this comparative advantage which provided the capital, skills and

experience to capture so much new maritime trade in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Figure 3 : Ship capacity (in 000 tons): Ragusa and Venice 1300-1600

Source: As for Figure 2

A prominent American historian of Venice, Lane (1973, p.379, p.381) notes this was

also the period in which Ragusa became “Venice’s most damaging competitor, bidding

cargoes away from the Venetians on all seas, even in the Adriatic…[as] their ships were

18

increasing in number and size”21. Other accolades include claims of Ragusean equality

with Venice, based on fleet size and tonnage about 1575. ( Luetic 1969). Fig. 3 may

seem to confirm this “patriotic hypothesis” as indeed in some years the two are very

close. However this is misleading and exaggerated as equivalence only occurred when

Venice had lost numerous ships during wars, as both in defeat and victory many ships

were destroyed, then the fleet was rebuilt to even higher levels. But at other times it was

significantly larger than Ragusa’s –and this is excluding the naval fleet which could be

used for commerce in peaceful times. Nevertheless that Ragusa’s merchant fleet could

even approach that of much larger Venice is strikingly impressive .given its much

smaller size and infertile

territory. The large maritime role it played is further

emphasized in a comparison with mighty England: about 1575-1600 the latter’s fleet

was about equal to Ragusa’s, approximately 50,000 Tons. OF course immediately after

that it expanded rapidly and outpaced both Ragusa and Venice by multiples.

Historians vary in dating the beginning of the decline, from early 1500’s to about 1600.

We use 1575 as the end–date based on the peak value of shipping tonnage (Fig.3).

Population began to decline even earlier (Fig. 2) , but Vekaric 1998)

attributes this

the plague and the “correction “ of excess population of refugees from Ottoman

advances, rather than the economic situation.

. If indeed shipping capacity is a good

proxy for otherwise unavailable economic activity data, one must tentatively conclude

that Ragusa’s

aggregate GDP continued to grow, population decline cannot be

attributed to economic decline., and of course GDP per capita continued to increase-a

question for future research.

21 This is also reflected in the work of Fernand Braudel who writes of Ragusa’s ability to “snatch away goods from under the eyes of Venetian merchants” as cited in Stuard

(1992)

19

There is a broad consensus on the reasons for the decline if not its timing:

the

discovery of the Cape of Good Hope eastern route by Vasco da Gama with the first

Portuguese colony in India in 1503. The far lower shipping costs compared to the

previous Levant route with onward land-transport, made Venice, Genoa , Ragusa and

other traders in the region overwhelmingly non –competitive. True , as the shipping

data suggest , and detailed studies of the spice trade show ( Carter , 1972 nd Lane

1973 elaborate ) , these traders continued to find new advantages ( including prior

monopolies, established networks with suppliers and buyers contacts) to offset the

higher costs ,maintaining their absolute if not relative position for a century or so.22 But

in the end the new route and enormous expansion of the Western fleets –Netherlands

and England came to dominate this trade Furthermore , this century was the beginning

of an economic growth surge in western Europe making these markets -already much

larger in

population - vastly more important than

Northern Italy. The center of

economic gravity simply shifted west. . In Venice this is remembered as ‘The Collapse”,

which eventually became

n ot just a relative but an absolute decline of its trade,

economy, naval might , and wealth.. So too for Ragusa.

After the decline from 1575-1750, a short revival occurred, not in population, but in the

size of the fleet (Figure 4), though the average capacity probably fell23. This revival does

not seem to be given much attention by historians, either because it is not clearly

understood, or perhaps because by this time the uniqueness of Ragusa /Dubrovnik has

22

This long period of continued competitiveness hints at another hypothesis common in modern studies of global

shocks : that small , open , and institutionally flexible economies have great resilience, and are bet at mitigating

external demand shocks.

23 Luetic (1969 m) and other fleet estimates generally agree on this.

20

long passed and academic interest in the later periods is not as great. The decline and

growing irrelevance of Dubrovnik continues in 19th c. as modern shipping and railroads

destroy all of its mediaeval advantages and other Adriatic cities dominate : Split , Rijeka

,Trieste. But the seeds of its 2oth c. fame are laid , as it becomes a popular summerretreat area for the wealthy in Austria Italy, and Northern Croatia. . Mass tourism would

come much , but bring fame and new fortunes.

IV ASSESSING THE QUALITY OF INSTITUTIONS

IV.1. Overview: Ragusa’s Main Institutional Strengths

Innumerable authors over the centuries have attributed Ragusa’s success to effective

governance based on a political regime of republicanism that may not have been

democratic but relatively fair and benevolent providing pioneering social provisions like

education, health care, quarantine systems, and provision of grain reserves for times of

shortage. To this was coupled a generally liberal, open economy, with prudent state

finances, limited market intervention, and encouragement of private enterprise. The

Croatian economic historian Vladimir Stipetic ( 2000, p.24): captures this nicely in a

recent article “Dubrovnik traded like Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan …but did so some

five hundred years before ..[and like these countries] became prosperous ..because of

their adopted economic policy .” In short , he suggests Ragusa was the Adriatic Tiger of

Mediaeval period, While this section focuses on institutions for which data could be

found -fiscal prudence; business contract enforcement, and fair and effective legal

procedures. given the widespread accolades for its effective republicanism , benevolent

21

social policies,

and diplomat skills

par excellence , we provide some qualitative

evidence of these too. Thus IV.2 summarizes the nature of republican governance, IV.3

looks at fiscal history, IV. 4 presents data on “ease of doing business”, IV. 5 shows data

on speed, and efficiency of courts. Social programs are considered in IV.6, and the

trade-off between military and diplomatic expenditures is discussed in IV. 7.

But first we address the main competing explanatory hypothesis in the literature:

Ragusa’s economic success was due to luck of location.

Many

historians

emphasize Ragusa’s location at the edge of the Christian and Muslim worlds, noting

that by sea it was close to thriving Italian cities and kingdoms, but by land immediately

adjacent to Balkan territories occupied by the Ottomans from the 14th c.

Filip de

Diversis (1440 ) devoted a full chapter to this, “De bono situ Ragusii” (The Good

Location

of Ragusa} noting

both

its politically favourable geographical location

between Christian and Muslim world , on the edge of Balkan hinterland , also on the

sea routes eastward ,and its allegedly

ample water resources. This last

is most

doubtful; indeed huge expense was put to provide water by viaduct from the Ombla

River-then a considerable distance over ten kilometers.

The “luck” explanation is further put into question by the fact that Ragusa was far from

the only possible intermediary on the Adriatic Coast, and in fact had much poorer

“natural’ advantages in terms of productive lands, easy water supplies, sheltered

harbours. Indeed many coastal cities like Kotor or Ulcinj to the south, and Split, Zadar

to the north had similar location , generally better natural resources, even larger quiet

harbors .All were also entrepot

traders

competing with

but never attaining the

prosperity of Ragusa. Geographically they too were “on the edge of Christian and

22

Muslim worlds”, but the Ottomans gave preference to Ragusa.. Why ? We have not

studied this explicitly and merely suggest two points: they recognized Ragusans were

far better entrepreneurs and traders ; and

Ragusa amplified these skills with very

effective diplomacy.

In short it is entirely logical to say that without the luck of such a location, Ragusa may

not have prospered, but it prospered more than other Dalmatian sites due to other

factors , primarily wiser policies to leverage the location into greater prosperity than

local competitors. This accords well with the view of Machiavelli (1966 translation ,

p.8) who briefly points to Ragusa as an example of his thesis on the ideal site for a city

: “it is better to choose sterile places for the building of cities so that men , constrained

to be industrious and less seized by idleness, live more united, having less cause for

discord, because of the poverty of the site , as happened in Ragusa.” In sum one

could accept that location was at most a necessary , but far from a sufficient condition.

IV.2. Effective Governance

Ragusa was by no means a democracy , government roles being almost entirely in the

hands of a hereditary nobility mythically based on the “original” settler families from

Epidaurus, though in fact in early centuries many rich merchants and Balkan nobles

‘were often quietly “ennobled” in return for financial

benefits they could bring the

state..24 Following the 1272 Venetian “Serratta” or closure of membership in the nobility

Ragusa did the same in the early 14th.c. But Ragusa differed in two critical ways. First

24

Vekaric (11) , Vol.1 shows in Table 7 the roots of the noble families; it is clear that a large proportion were not

from Epidaurus. Illustratively, and indicative of name roots is the case of one of the most powerful , the Sorgo

(Sorgocevic). They were rich merchants from Cattaro in Albania, “ rewarded by the Grand Counci lfor bringing

large amounts of sorghum and other victuals to Ragusa, at the time of the great shoratges in the year 1292” ( see

p.68 for Italian original text. )

23

while it also had the Senate elect a head of state -Rector after 1358 “independence”

from Venice- he served ffor one month at at ime, essentially a titular head with some

managerial responsibilities. Thus, Ragusa avoided the Venetian evolution of informal

dynasties which came as a result of Doges serving for very long periods , able to

impose their personal or family interests into state affairs.

Second and more important Ragusa did not follow Venice’s “Serratta “ which imposed

a monopoly of commerce for those in the new list of nobles25 Ragusa did not create this

monopoly, and

allowed new commoner

entrepreneurs to

enter commerce.. To

understand the importance of this, one need only think of how much emphasis is put

by modern development thinking on promoting new entrepreneurs, small and medium

enterprise

with

such reforms as simplifying procedures for opening and running

business By itself this is already strong evidence of institutions favorable to commerce.

It follows this open environment probably contributed to the economic prosperity of the

Silver and Golden periods--

though we leave to future research testing of this

hypothesis.

This crucial orientation to promote commerce by avoiding monopolization not only

explains the good institutions we discuss later , but also the relatively benevolent

position towards commoners , whose “voice” while

was heard in two ways:

not manifested in voting rights,

some rich merchants and skilled professionals were given

positions in government26 ; and the poor were not ignored in noble’s deliberations for

provision of many social programs. It is widely agreed by historians contemporaneous

25

True, the list was in 1272 greatly enlarged to co-opt then existing major merchants,but new ones were not allowed

, or at a minimum highly constrained.

26

Many writers note that in very early years before about 1200 , in fact “Agora democracy” did exist with

assemblies of all citizens (The Laudo Populii)-making key decisions. E.g. Carter 972-p.500)

24

and modern, that compared to most other states/nations in this period the nobility

ruled with a relatively soft hand and provided considerable support to meet the needs

of the populace. Thus Grubisa (2011) shows Ragusa was perhaps less open than the

Florentine system of “democratic republicanism:” (and

thereby more stable, he

contends), but it was far more concerned that the basic needs of the populace were

met, than was the case in most regimes of that period such as the very narrowly-based

republicanism of Venice.

The Ragusan political regime

might thus

be most

appropriately characterized as a benevolent oligarchy rather than a rapacious one.

From the early 14th. c. movement by rich merchants into the nobility was indeed rare ,

but real upward mobility did not cease. That non-noble merchants

had great indirect

influence –indeed increasing influence -is made clear in the literature , for example in

Krekic (1980, Ch. XIX) , who characterizes the regime rather nicely albeit somewhat

sardonically

as a “ government of the merchants , by the merchants, for the

merchants.” Most importantly as we elaborate below ,the governing class generally

meted out justice not arbitrarily in a feudal fashion, but on the basis of laws , legislation,

judicial process- in today’s jargon ROL. The start is in legislation , best symbolized by

having a very early a constitutional document –the 1272 “Liber Statutorum Civitas

Ragusii” -

which codified earlier laws

and informal practices . While many

shortcomings in practice are noted by historians , numerous instances of well-applied

justice in the law in practice are also found in the literature.27 reflecting the nobility’s

admittedly self-serving but nevertheless “reasonable” treatment of commoners , rich or

poor. .SIsak (2010) typifies the literature’s consensus when he argues this rules-based

27

We note on example using a quantitative review of 2,440 court cases, Lonza(02). She concludes large numbers of

cases were settled out of court, a practice authorities encouraged.

25

treatment of the populace helped contribute to the long-term stability of the Republic,

with virtually no significant peasant uprisings as seen frequently elsewhere, and far

fewer internecine revolts within the elite.28

The legitimacy of the nobility was to a large extent a myth but the other side of this coin

was that it was not nearly as rigid in practice as in the law. Vekaric (2011) and earlier

others –Krekic (several works) Kedar (1976),

Carter(1972)- document the shifts of

noble lineage, the impoverishment of many noble families, and the rapid growth of

wealth of non-noble merchants who before 1400 were gradually and volens-nolens

“absorbed ‘ into the nobility29, or at least into

the ruling elites

and

government

officialdom.

A quantitative indicator of informal upward mobility is the increase over time in the

share of credit issued by commoners, which ,Krekic(1980) estimates for the years 12801440 was already about one third- Zlatar (2007-p.139) gives a higher value of 42%. An

imperfect but striking statistic suggesting continued upward mobility is in Luetic(1969p.101): by the mid-18th.century, of 380 registered ship-owners , only 80 were of noble

class..30 Indeed it is from the non-noble ship owners category that perhaps “the richest

man in Dubrovnik “ in the 16th c. arose, one Miho Pracatovic from the island of Lopud

( Tadic ,1948, p.143). He is recognized by most historians not only for his great wealth.

But also

for his

tremendous informal influence, symbolized by the fact that a

monument to him was erected in the “sanctum sanctorum “ of the nobility, the courtyard

28

The failed efforts of a revolt about 1402 and the short-lived and futile one by Lastovo island nobles being two

major exceptions ),

29

As noted the closure made this rare , but not impossible.

30

This is not the actual share of the value just the number of people , hence it may overstate the role of commoners.

In the Zlatar data, the size of holdings was higher for nobles; we have not found evidence for later years.

26

of the Sponza Palace ( Krekic ,1997, Ch.I, p.p.253-255). Another ship-captain from the

island of Sipan , Stjepovic-Skocibuha is considered in the same category, who allegedly

refused an offer to become a noble. Krekic dismisses this as unlikely, but a motivation

for such a refusal existed: it is often written by historians –Krekic first among them – that

many nobles fell into poverty because “noblesse oblige “ required so much time in

various government duties as consuls, judges , treasury officials , that they did not pay

enough attention to their commercial ventures. It is not impossible Skocibuha thought

twice whether nobility was worth more than wealth and the “:eminence grise “ influence

the later permitted. In conclusion it is clear that upward mobility continued , a factor of

great relevance to the central argument of Sec. IV..4 that Ragusa provided a good

business climate.

IV.3.Evidence on fiscal prudence

Ragusa is thought to have practiced a very prudent policy with respect to state

finances, debt, expenditures , as well as minting of currency. .Quantitative evidence

under this rubric in is available for only one very late period, about 1800, but not for

earlier. But indirectly it points to prudence in earlier periods : interest expenditures are

unusually low, and a strong positive asset position is evident in very large dividends

earned. Furthermore, numerous qualitative references in the literature point to

the

same conclusion. Consider first the available fiscal data.

Figure 4 summarizes the percentage structure of revenues and expenditures in about

the year 1800 ( not further specified) based on a later report to the new Austrian

27

Governor after 1815 , by a financial expert named Bara Bettere, later translated into

Croatina by Krizman (1952). The absolute data , not shown , point to the first important

conclusion : the budget has a surplus of about 10% of Revenues., fully consistent with

the prudence hypothesis. There is unfortunately no such data to confirm this prudence

in earlier years, though the richness of the Dubrovnik Archives with myriad financial

documents might make this feasible with considerable research effort. But the Bettere

numbers on interest payments and dividends received by the state point to as trong

fiscal position in preceding decades at least. Tab. 4 shows very low interest share of

1.7% of the budget far below what was common in the region for those centuries. Thus

Lane (1973) estimates that at this time Venice paid out a third –and even more in earlier

years-to service its debt .Kormer (1995) analyzing about 25 kingdoms, principalities and

city-states from 1500 to 1800 ( not including Ragusa), concludes that “service on the

debt varied between 17 and 36% of total expenditures.”

The main message in the

popular work of

Reinhartt and Rogoff

This Time it’s

Different (2009) is that the current recession is NOT that different from earlier ones

over centuries, and points to the fact that high debts and defaults were very common

in European economies historically. In contrast, the historical literature on Ragusa we

have researched so far does not give any specific instances of debt defaults... Perhaps

equally important , it appears that all or most Government borrowing was domestic,

either from the Zecca (the MINT) or the elites. The latter were however often obliged to

provide lending at low interest,- in Italian cities these were referred to as “imprestiti” ,

best translated today as “forced loans.” ( Cipolla , 1986) .When financial difficulties

28

occurred –and they did – they had to accept “haircuts’, reduced repayment,

restructuring and the like. 31

Figure 4: Structure of Ragusa Budget about 1800.

Sources: Shares are calculated using absolute ducat values in Krizman (1952)

Indirect evidence of earlier prudence is in the very high share in Revenues of dividends

earned, at 25.3%. Ragusa’s net asset position was strongly positive with large amounts

of deposits held in Italian banks and by 18th century in Vienna. In Author (2013), some

Krekic in his many writings ,as well as others (Sisak(10) discussing the role and obligations of the nobility” , note

that in this small noble group, it was a “social obligation” that services be rendered to the state not only in the form

of time in political and bureaucratic positions, consular activities, but also by “sharing “ proportionately in lending

to the state when exigencies arise, or accepting less than full payment on previous loans.

31

29

numbers for 15th.-17th.confirms Ragusans held considerable private deposits in the

“Monti” or Funds : of Italian banks.

For earlier centuries, qualitative assessments of Ragusa’s prudence and conservatism

throughout the centuries abounds, starting with contemporaneous writers like Diversis

and Kotruljevic, first noted the sensible financial stance of the Republic. More recently

Stipetic (00-p26ff) notes that

adding

“precise books were kept on the finances [of the state]”

that prudence was ensured by “requiring the

main officials in charge –

registrars, clerks and accountants …must be foreigners [In addition ]there was the

institution of auditor with power of supervision of communal goods, a duty to investigate

whether revenues are collected fully and expenditures are viable, not spent for

unintended purposes.” They served five years when new ones were elected... Stipetic

recognizes that the system was not perfect, indeed that building barns with doors

implies horses do run out, that is corruption does occur. Krekic (97-p.32-5) notes the

reality of bribery, but concludes that efforts to curtail it by punishing offenders were

generally as effective as can be expected.

Thus both the qualitative evidence on fiscal prudence in early centuries and the harder

budget data of 1800 are very consistent with the hypothesis that Ragusan finances

were generally strong, prudent, able to absorb shocks. Incidentally, Figure 4 gives

numerical credence to the observation of Carter (72.p.535) about the enduring nature

of this financial prudence -that even at the end, in 1806 after French occupation, “the

state’s finances proved still to be in good condition in spite of all the troubles and the

requisitions, and large sums were invested in Italian banks.”

30

IV.4. Evidence on “ease of doing business”

It is generally agreed that Ragusa’s government was strongly commerce and trade

oriented , and the ruling nobility understood well this was the basis of their wealth. It

would seem they also understood that it was necessary to extend this good business

climate for commoners as well , which spawned a flexible and adaptive merchant class

quickly able to react to demand changes or external shocks, seek new markets, adapt

trade routes, change products. The frontispiece citation from de Diversis on institutions

symbolises how this attitude was already well established by the 15th c. Historians’

writings contain innumerable references as well as illustrations of this business friendly

environment. The new contribution of this paper consists of providing some quantitative

evidence of this. We start with Tables 2 and 3 which respectively quantify the timelapse for a number of

bankruptcy cases as given in the literature, and the share of

notary entries for commercial and personal activities.

In Table 2 for a benchmark we note from the World Bank Doing Business Report (2013)

that in 2012 , the average time to complete settle a contract dispute in different regions,

a now-common measure

of the ease of doing business in modern

analysis. The

shortest was about 1.7 years for the OECD countries , the longest was 3.4 for the

Middle East and North Africa region – though for some individual countries it was much

higher. Note the value of 3.1 for Croatia today.. For Ragusa in the 16th c the the very

limited information available gives a range of 1-3 years to complete a bankruptcy case

brought to courts.. True the sample is small,,one has no idea how systematic it is ( in

both sources the information is only vaguely presented) start times and finish times are

not always explicit or precise, and sometimes not stated at all. Hence our conclusion

31

has to remain very tentative and conjectural. If however if the real time-range is even

double this ( 1.5 -6.0 years ) this would still seem very efficient for the times, given

realities of travel, documentation etc. In fact many of the cases shown here deal with

Ragusan ventures in other countries/states , which even today would

complicate

matters and generally add to the time required.

TABLE 2. TIME FOR BANKRUPTCY PROCEDURES RAGUSA 16th and 17th. c.

Year/

Nature of

Years

Period

Case

To

Source

Time to

start

Final

2012

WB Doing Business

-

Report 2013

www.doingbusiness.org/d

ata

2012

2012

2012

Dec.1566

1577

(Sept??)

BEST:OECD high y

WORST REGION:

Mid.East.N.Africa

CROATIA

MEDIAEVAL RAGUSA

CASES

Nobles Sorgocevic&Lukarevic

Florence/Venice

business

bankrupts;Rag & Italian creditors turn to

Ragusa courts, some local assets frozen

immediately-final decision May 1570

Joint business of Cveta Zuzoric&

husband Peshonija fails, immed. Put

under oversight , claimants given 3

1.7

3.4

“

“

3.1

“

3.3

Tadic(48)

pp.287ff

<week

2.5—

(but

new

Tadic (48)

pp.327 ff.

3 days

32

Year/

Nature of

Years

Period

Case

To

Source

Time to

start

Final

1575

1571

days to file claims with court notary –

numerous do -- court process begins,

most seem done/agreed/decided by Mar

. 1580, but new claims arise as late as

1583

Ivanivic&Dabovic Ragusa merchants in

Serbia bankrupt, courts seized Ragusa

assets against claims of 5,850 ducats.

In judgment they were to send 860

ducats value of ox-skins immediately,

pay rest in yearly annuity at 6% interest

(no further time details given

A partnership in Smederovo and

Belgrade, but registered in Dubrovnik

1565 , announced bankruptcy:

but

creditors proposed continuation with

restructuring (“sanacija”), and accepted

annual payment of 200 talers

claim in

1583)

About

1 yr.?

Palic (08) p.79

???

n.a.

Palic (08)

p.79

Seques

ter

Within

dys.

Weeks

??

Source: author’s compilations from writings noted in Table

Historical references to bankruptcy which do not give time-lapse statistics are much

more frequent , and they generally describe the Ragusan system as very efficient,

effective , and even-handed. Palic(06/07) in particular emphasizes the thoroughness

and speediness of the process, the comprehensiveness of the underlying law and

practices which contain many

terms familiar even to the present day : sequester,

liquidation , restructuring (sanacija in Croatian ),rescheduling of term , etc. He claims

(p.23 ) that ‘at that time , Dubrovnik was admired by Europe for its court procedures

methods , being the exception from the middle ages darkness, showing justice and

honorableness.” Speed and efficiency of courts in all cases , civil and commercial ,is a

point also made by others such as Nella Lonza whose works are the basis of the next

33

sections.It is also noteable that the apparent time required

to initiate cases in the

courts, time given creditors to file claims, was very short—a matter of days or weeks.

This is consistent with the qualitative judgments about court efficiency in the literature.

Palic (2006 &2008) describes briefly numerous cases of bankruptcy of Dubrovnik

merchants in Balkan states/cities, but details are not always complete: in some cases

amounts are given of debts, repayments, in others partially. In most cases a year is

given for the initial bankruptcy insolvency, but not for time for making claims, or dates

for final resolution. Hence we do not include them in Table 2 , but it is abundantly clear

in these articles that most cases once started went through a

thorough process

apparently speedy in the early stages, even if the two parties kept returning to courts to

obtain satisfaction, sometimes after a long pause , and therefore any final resolution

may have taken years.

Palic (08) further attests to another aspect of bankruptcy which demonstrates a

favourable business climate; (p.83) unlike the “debtor’s prison” practices elsewhere “the ultimate aim of bankruptcy…was not just settling [with] the lenders, but it was

rightfully considered … helping the debtor overcome the state of inability of paying their

debts… creates an atmosphere for further co-operation and doing business together.”

This tendency to encourage out-of-court settlement is also seen in the general activities

of

courts

beyond

cases

of

bankruptcy

presented

below.

In modern quantitative analysis of institutions perhaps the first and most common

measure is days and costs needed to start a business We have not been able to find

34

data approximating this concept in the secondary literature—though this may be

obtainable in the rich Dubrovnik Archives . However , it would appear that starting a

business or venture was frequently done by a relatively simple process of registration

with an official Notary., apparently uncomplicated and almost immediate as is the

case in many advanced countries today.

In Table 3

32

showing the percentage

distribution of 1,492 Notary entries in the years 1299-1301, such a measure is not given

but we see indirect evidence of the extensive use of notarization If we consider

Testaments, Dowries , and Personal Service and Employment notarisations as personal

at least 33 % of notarizations are business related—starting or operating a venture,,

dealing with debts , sequesters, guarantees. In fact this must be a lower bound, since in

TABLE 3. RAGUSA NOTARY ENTRIES BY CATEGORY 1299-1301

# OF

ENTRIES

PERCENT

TESTAMENTS

149

10.4

DOWRIES

68

4.7

SERVICE/EMPL(zaduznica)

741

51.9

APPRENTICESHIP

39

2.7

AUTHORIZATION(punomoc)

29

2.0

RECEIPT/VOUCHER/AUTHORIZATION/POWR

OF ATTORNEY

13

0.9

PROPERTY TRANSACTIONS

171

12.0

GOODS TRANSACTIONS

119

8.3

SHIP/CARGO TRANSACTIONS

19

1.3

BUSINESS/PARTNER AGREEMENT

17

1.2

CATEGORY

32

The data are compiled from an extremely informative listing by Lucic(1993) of all such entries by just one notary;

the list not only transcribes each from the Archival Notary books, but defines the category, provides an overview of

the process , and an extensive index of individuals named , which allows some further analysis in later tables.

35

# OF

ENTRIES

PERCENT

DEBT

1

0.07

COLLATERAL

40

2.8

APOHA (related to collateral )

15

1.0

GUARANTEE

3

0.2

FRAGMENT ( this may be incomplete

information )

5

0.3

1429

100.0

CATEGORY

GRAND TOTAL

Source : Authors’’ computations based on Lucic (1993)

Testaments there were surely business-related elements, as well as in the rubric

Services ( in household ) and Employment., and even Dowries – which were often

designated for partial commercial use.

The qualitative evidence of ease of doing business merits some elaboration and we

show below it almost universally confirms the conclusions implied by the data. That

well-functioning notary and registration procedures and records for business contracts

were established at least as early as the 13th century are referenced by many writers,

and according to Stipetic(00-p. 18), existed from as early as 1200 , with formalization in

the 1272 Statut (Constitution). Further details established In 1277 this was expanded

by the Customs Book, with a focus on economic rules. That Ragusa was among the

earliest states to formalize commercial registration and contract procedures is a

common claim of its many historians. All of the above imply such an early development ,

and their periodicity , at least as early as the beginning of the 13th c., does suggest it

was among the first to implement “pragmatic literacy”

33,

only marginally later than

33

A term suggested by Nella Lonza in a private communication , in which she also indicates the beginnings of

document formalization in Italian cities, in the 11 th C., with Zadar probably the first in Dalmatia,soon followed by

Ragusa

36

Italian cities and the first Dalmatian city ,to do so, Zadar. Dates for Western Europe

given

by Kuran (2011, p.242 ) allows a broader comparison : “In Venice written

contracts became mandatory on matters of importance [in court cases-au.] in 1394, in

France in 1566, in Scotland in 1579, and in Belgium in 1611. In England they became

mandatory on all contracts with the Statute of Frauds of 1673.” Kuran (p.243) also

mentions that the first agreement of Ottomans with western trading states imposing

documentation requirements for court disputes involving foreign merchants, was that

with Dubrovnik in 1486, preceding the Mamluk-Florentine treaty of 1497 which did the

same, and one of the most important “capitulations “, that was agreed with France in

1536. It needs verification to

ascertain whence came the initiative for the 1486

Dubrovnik agreement, but given the history of passivity in

Ottoman actions and

initiatives of Dubrovnik trading efforts, the best quess would be from Dubrovnik.34

Many other early institutional elements that today would be labeled

“a favorable

business and rule-of-law climate” , can be pointed out. Thus Luetic (1961-p.107), and

Carter (1972 –p.157) note the beginnings of the first maritime insurance policies were

organized as early as the 14th c, while Doria (1987) discusses how thoroughly this had

become elaborated by

procedures in 14th-15th c.

the 16th.century. A revealing description

in several articles

by

of bankruptcy

Palic ( 2006.a, 2006.b, 2008 )

concludes in (2006.a –p. 23) : ”court decisions … were kept in very thorough transcripts

with notified damage compensations, punishment types and dispute settlements .” he

also claims that “at that time, Dubrovnik was admired by Europe for its court procedure

34

The depth of formal and informal institutional support for commercial activity is also evidenced by the renowned

richness of the Dubrovnik Archives –the records are so large that it required 61 pages for Carter (72 Appendix 3,)

merely to list the names of documents, under 40 categories such as Council Proceedings, Miscellaneous Notary

Documents, Manufactures, Customs, Administration Receipts , Expenditures, Acquisitions,etc.

37

methods, being the exception from the middle ages darkness , showing justice and

honorableness.” 35

The early and pioneering development of modern accounting by Kotruljevic (1440) is

described by . Stipetic (2000-p32) as well as Krekic in his many works , and several

others . Indeed there is now solid scholarly evidence that this was the first formalized

‘handbook “ on how

all good merchants/traders should

accounting books, use double-entry bookkeeping,.

36

maintain balances in

use banking instruments for trade

such as bills of exchange, letters of credit. This alleged “first ‘ has put on the table of

the modern accounting literature a debate : was the first as was always considered the

1496 manual of Venetian Lucca Paciolli, or should this honor be given to Kotruljevic’s

1440 chapter on double-entry ?The issue is beyond the scope of our paper, and we

leave it at the following; in a personal email communication from the Dutch scholars

Postma and van Helm

they suggest that while indeed Kotruljevic briefly describes

double-entry bookkeeping in 1440 , the first truly complete manual on how to do it, and

the one which had the greatest future impact was that of Paciolli in 1496.

But for the argument in our paper about early presence of good institutions, , the nowaccepted fact that Kotruljevic did have such views and wrote them in a manuscript

passed around manually,

is clear

evidence of the right attitudes to promote

commercial activity and prudent state finances. Indeed .Kotruljevic was also very early

in the history of economic thought expounding views that were very radical for the times

35

While this claim is consistent with other writings, unfortunately Palic does not provide references to European

writers of the time to substantiate this claim.

36

Stipetic(00) refers to non-Croatian scholars – presumably less-biased- who have found clear evidence that

Kotruljevic was the first to develop double-entry book-keeping, in 1440,well before the 1496 work of Lucca

Paccioli which had earlier been thought to be the first. ,

38

, such as interest being the price of capital,; credit being critical to fuel commerce and

only usurious if excessive ( 5-6% was his proposed limit) ; His 1458 treatise “Il Libro

dell’Arte di Mercantura” argued all these were requirements to achieve prosperous

trading, and not least important he noted the need for the state to ensure an open

mercantile and trading environment conducive to making money, creating wealth ,

minimal interference of state in commerce. , prudent

state finances. Kotruljevic

presaged by six centuries today’s received wisdom about ROL and a good business

climate. He would well deserve honorary mention by the World Bank’s Governance

and Doing Business Report.

Numerous writers state that the first quarantine station in the Mediterranean was

established in Ragusa in 1377 (the Lazareti,which were

eventually moved to the

mainland still stand today as a commercial-entertainment centre).Three recent studies

by public health specialists explore this world-first:: Frati (2000)., Lang and Borovecki

20(01), and Cliff, Smallman-Raynor and Stevens (2010) While thje quarantine station

might

be

considered a social fairness measure Frati documents extensively

deliberations of the Great Council confirming that the motivation was first of all the

need to continue doing business. after the first waves of the Black Death.

In sum considerable evidence in the form of indirect quantitative measures of business

related formalities, bankruptcy treatment in courts, as well as extensive qualitative

indications from historians , strongly suggest , that the climate for commerce, or doing

business in the modern jargon, was quite favorable.

39

IV .5. Evidence on Effective Rule-of-Law

Numerous historians

emphasize the rules-based governance of Ragusa and its

relevance for the prosperous economic development; the spirit of which is succinctyly

captured in the frontispiece citation from De Diversis . Stipetic ((2000) provides a good

overall summary of the favorable legal basis and practice of Ragusa and adds a vivid

history of Ragusan writings on economic theory.

But with the exception of several

works by Lonza which we rely upon considerably in this paper, the literature is largely

non-quantitative We will begin by presenting some selective quantitative evidence ,

sometimes indirect, which is consistent with the view that ROL was established early

and was generally implemented effectively and fairly; then we will add some qualitative

evidence for the literature to buttress the case.

TABLE 4: RAGUSA 1299-1301 NOTARY ENTRIES RELATIVE TO POPULATION

#of Individuals named

City

Republic

2,00038

2,000

3,066

3,066

Population

Range 37

(4,000)

(7,000)

(10,000)

(15,000)

% of Population

using Notary

50

29

31

20

Source: Author’s calculations based on Lucic(1993) and population estimates as discussed in Author (2012)

We start with some data on the use of a Notary in very early years ,1299-1301, based

on the work of Lucic (1993) covering 1,492 Latin entries involving 3,066 individuals,

already used for

Table 3.. In Table 4 we

calculate approximately the percent of

population involved in those entire, as an indicator suggesting that Ragusans utilized

37

No reliable estimates exist much before 15th.c but many historians seem to accept range 14th c. of three to four

thousand in city, a total of 10,000 -12,000 for Republic ( see Appendix Table 1) . To avoid overestimating percent

column we use range of 4-7 thousand and 10-15 thousand respectively

38

Author’s rough guess, based on details of entries suggests large proportion from city – we use 2/3. Even when

entry deals with activity outside city , it often involved city people , not surprising as wealthiest lived there.

40

formal notarization procedures quite extensively. As population estimates for this period

are not very solid, and not verifiable, we choose numbers that bias against our claim.39

Taking them at face value suggests

that anywhere between 20% and 50% of the

population was involved in some way – surely a very substantial and wide coverage of