Analyzing the Main Part of the Story Analyzing the Structure of the text

advertisement

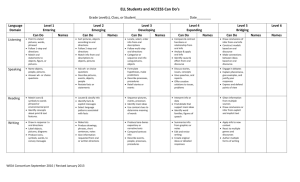

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background The objective of the English teaching program is to equip students with the four basic language skill, listening, speaking, reading, and writing. To achieve the objective, it is necessary to consider the English discourse anlysis and its contribution to the teaching of English. The practical treatment of Enlish discourse analysis will help us attain the competence of perception and production of English in real use, both in the classroom and out of it. The practical discussion cover four basic concept, they are: 1. The basic concept of discourse in relation to its theoritical linguistic background. 2. The relation between discourse analysis concept and language, particulary second and first language teching- learning activities. 3. The relation between discourse and language function in their social contexts 4. The application of the theoritical principles and practical procedures to the various kind of discourse. English is taught from yunior high school up to university that is known as tertiarry level as compulsory subject. This means that the students have had opportunities to learn English for many years and some still beyond informal classes, but they still perform low ability in analyzing it. Some researches have Page | 1 found that English students that dedicated much time foer English could not analyze English discourse as well as expected. It means that students learning out come is still considered as unsecsessfull teaching of English in Indonesia So, in this case, it is important to discuss the practical aspect of discourse. The practical aspect of discourse will make us competent enough to pick up some example of discourse from the real life around us and analyze systimatically. We have, of course, to apply the teoritical principle we have learned from the teoritical treatment of discourse. The practical experiences that stand on the background of their theoritical basis will become very significant for us because in this special mode of human interaction, we must need to comprehended perfectly when we communicate wth our fellow native speakers or foreign counterparts. Also we must need to catch clearly and correctly when somebody means something to us with his his utterence or discourse. English teachers have many handicaps. One of them is the students low ability in English discourse analysis. It means that the mastery of English discourse analysis needs much time to practice it. Realizing such condition in English class, English teachers should be more creatively look for the best way for communicative activities that urge and motivate the students to improve their ability to master English discourse. We are not supposed to forget our prospective profession. In this sphere, a touch from concept of discourse in the study of language teaching learning Page | 2 processes is very significant. This is why a discussion on this writing becomes inevitable. Ashort and compact deal with it organized a bit early. This study, with the name “ discourse analysis of an English narrative discourse”, is a final assigment of discourse analysis lecture. It has a very close relationship to some courses. They are: 1. Introduction to linguistics 2. Sosiolinguistics 3. Advance listening 4. Advance speaking 5. Advance reading 6. Advance writing 7. Cross-culture understanding English language teaching should be targeted at developing students’ ability to understans and express meanings. In understanding and expressing meaning of course use the form of linguistic units. The forms of linguistic units may have meaning only if they meet certain rules. This study will lead us to the ability of identifying the main characteristics of a discourse. Beside, it will also gves us the capability of identifying the similarities and dissimilarties between discourse as a structured ofunit and a unit consisting of ununfied sentences in terms of those main characteristis. A discourse is claimed to be unit of language in a real communication( Widiati, et. Al 2006). In connection with it, this study will also provide us with a Page | 3 chance to observe how a discourse plays its important role in the reals verbal communication. In using sentences in speaking and writing, we are concerned with language use at the discouse level which involve form, meaning, and language function. Thus, language learning would be meaningfull if the students learn expression at the discourse level as opposed to words in isolation. In using sentences in speaking and writing, the mastery of structure and focabulary are very important to support the process of the meaningfulness of the English communication. Thus, the mastery of using sentences in speaking and writing must take discourse analysis into consideration. The study of discourse lies on the bacground of the broarde field of the study of language, i.e. theoritical linguistics. To achieve a well-grounded compregension of this study, we would better start from the overview of language. Language is a system of signs (Chaer;1994). The key word in this identifcation is the term sign. A sign is understood as something that stands for something. The first something is the formal aspect of sign,whereas the second one is the meaning aspect. The professional English teacher has to prossess the adequacy of system of signs competence in English. He should be able to use the result of linguistic studies into the language teaching models. Some of the result linguistic studies talk about English discourse analysis. In this case, it is important to consider the formal aspect of sign. The formal aspect is physical so that we will have to use our sensories to sense it. We use our Page | 4 ayes if it is visual, our ears if auditive, our feelings if tactile, and our nose if elfactory, It is also important to consider the meaning aspect of signs. The meaning aspect is psychological. It is an image of thing, or a state, or an activity that underlies the formal aspect. It is also social in the sense that the relation between the formal aspect and its underlying meaning is determined by the agreement from the society. In linguistic studies we study on phonems, syllable, morphemes, allomorph, lexicon, words, phrases, clauses, sentences, and discourse. (Ba’dulu 2003 ) they are related to the cases of discourse analysis. In the proficiency of discource analysis garantees to produce sentences in speaking and wrting. Bse on the desccription above, the writer wants to caarry out a study entitled The Discourse Analysis of anEnglish Narrative Discourse. B. Problem Statement Based on the background above, the writer formulated the research question as follow: 1. How English narrative discourse is analyzed based on Thurman chart. 2. Are there anykinds of information in the English narrative discourse. C. Objective of the Research The objective of this reseach are as follows: 1. To discribe The English narrative discourse based on Thurman chart. 2. To discribe that kind of information in the English narrative discourse. Page | 5 D. Significance of the Research The result of the research is expected to give: 1. The input to language teachers, especially English teachers, in adding their comprehension on one of the linguistics features, that is in this case English narrative discourse baesd on the Thurman chart. 2. The input to the English instuctor to create their course in leading the English teacher training. 3. The concept of English narrative discourse based on the Thurman chart as well as its contibution to English teaching 4. The input for further reseaches related to English discourse analysis. Page | 6 CHAPTER II REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE A. Theoretical Framework 1. The Meaning of Discourse Analysis According to Keith Johnson and Helen (1999:99-105) cited in Ba’dulu (2007), discouse analysis is the study of how streches of language used in communication assume meaning, purpose and unity for their users: the quality of coherence. There is now a general consensus that coherence doesn’t derivr solely from the linguistic forms and propositional content of a text, though these may contribute to it. Coherencederives from an interaction of text with given participants, and is thus not an absolute property, but relative to context. Context includes participants’ knowledge and perception of paralangue, other text, the situation, the culture, the world in general and role, intensions and relationships of participants Early attempts to find linguistic rule operating across sentences boundaries, or to create text grammars specifying rules for generating possible sequences of propositionhave generally been replaced or supplemented by theories and techniques allowing the examination for text in context. Prominent among such theories and techniques are functional analysis, Pragmatic theories of speech acts and converational principles, conversatio analysis, schema theories, genre theory and critical discourse analysis. Discourse may be define as language that is doing some job in some context, i.e. in some contextof social situation (Nuryanto, 20006). Thus, discourse anlysis is essential attempt to analyze and describe how language Page | 7 performs its role in various contexts of social situation, i.e. in various social activities. As the role of language cannot be separated from its context of social situation. There are a number of different approches to discourse analysis and there is often some of disagreement and confusion about the meaning of both terms “ discourse” and “ discourse analysis”. The approach describe above may be characterized as the British- American School, and has been the most significant in applied linguistics and language teaching. It is, broadly speaking, an approach which has merge from detailed study of language. Confonted with the absence of lingustic or semantic explanations for coherence, it has sought help from other diciplines. Historiclly, it has moved from consideration of most local textual phenomena, such as cohesion, towards more global concepts such schemata and genre. From the difinition of discourse as language doing some job in some context ( of social situation) we can draw the conclution that a discourse is a of language use that fulfills a certain fuction in acertain social activity. In practically of all our social activities we involve language to fulfill a certain function. In performing such social activities as education, bussiness transections, scientifie investigation, religious services, or even in playing games we have to use language. Each of these social activities can be accomplished only by involving language. Page | 8 2. Historical Background of Discourse Analysis Discourse analysis is both and old and a new dicipline. Its origin can be traced back in the study of language, public speech, and literature more than 2000 years ago (Ba’dulu.2007). One major historical undoubtly classical rhethoric, the art of good speaking. Whereas the gramatical antecedent of linguistic, was concened with the normative rules correct language use, its sister dicipline of rhetorica dealt with the concept for the planning, organization, specific operatons, and performances of public speech in political and legal settings. Its crucial concern, therefore, was persuasive effectiveness. In this sense, classical rhetoric both anticipates contemporary stylistic and structural analysis of discourse and contain intuitive cognitive and social psychlogical notions about memory organization and attitude change in communicative contest. Discourse in communicative contest implieds that discourse is primarily language; however, it is language that exist independently, apart from the daily life of its speakers. Discourse is language that is functional in some context of social activity. Indeed, discourse may be viewed as the VERBAL. EXPRESSION OF SOCIAL ACTIVITY Whereas the 1960s had brought various scattered attempts to apply semiotic or linguistic methodes to the study of texts and communicative events, the early 1970s say the publication of the first monographs and collections wholly and explicitly daling with systimatic discourse analysis as an independent orientation or research within and across several diciplines. Page | 9 3. Discourse-Level Structure According to Cristal (1980) cited in Ba’dulu (2007 ) discourse is a term in linguistic to refer to a countinous stretch of ( especially spoken) language larger than a sentences- but within this broard notion, seveal different applictions may be found. At this most general, a discourse is a behavioral unit which has a pretheoritical status in linguistic; it is a set of uttarances which constitute any recognizable speech events (viz. Reference being made to its linguistic structuring if any); e.g. a conversation. A joke, a sermon, an interview. A clasification of discourse functions, with particular refrence to type of subject – matter, the situation, and behavior of the speaker, is often carried out in sociolinguistic studies ( of permitive societies in particular), e.g.,distinguishing dialogues, or morespecially, oratory, ritual, insults, narrative, and so on. In recent years, several linguistic have attempted to discover linguistic regularities in discourse (discourse analysis), using gramatical, phonological, and semantic criteria ( e.g. cohesion, anaphora, inter- sentences connectivity ). It is now plain that there exist important linguistic dependences between sentences, but it is less clear how far these dependences between sentences are systimatic to anable linguistic units higher than the sentences to be estabilished. Some linguistics would like to use the termtext and discourse intechangeble. Some use text consistenly including the idea of discpurse. Some others would like to make distiction between text and discourse,. Cook(1989), forinstance defines a discourse” stretch of language precieved to meaningful, unified, and purposive. Page | 10 Longacre (1981 ) cited in Ba’dulu (2007) state that the term” discourse” as currently used, covers two areas of linguistic concern: the analysis of dialogue especially of live conversation- and the analysis monologue. In the parlance of many, discourse covers the former, and with at least some of us, discourse covers thel latter. Actually, the two matters- analysis of monologue are sepeable but related concerns. Dialogue analysis can properly be applied to both. 4. Discourse Typology in National and Surface Stuctures We can classify all possible discourses according to two basic parameter: Contingent temporal succession and Agent orientation. Contngent temporal succession ( hanceforth contingent conteporal) refers to a framework of temporal succession in which some ( often most) of the events of doings are contingent on previous events or doings. Agent orientation refers to orientation towards agents with at least a partial identity of agents refrence running through the discourse. These two prameters intersect so as to give us a four way classification of discourse type; narrative discourse ( how to do it, how it was done, how it takes place) is in respect to contingent succession ( the steps of a procedure are orderd) but minus in respect to the agent orientation ( attention is on what is done, or made, not on who does it). Behavioral discourse ( a broard category including exhortation, eulogy and political speeches of candidates) is minus in regard contingent succession, but plus in regard to agent orientation ( it deals with how people did or should behave). Expository discourse in minus in respect to both parmeters. Page | 11 For the purposes of surface stuctute classification, the two parameters can be redifined. Thus, rather than speaking in the abstract of contingent succession, we can speak more concretly of chronological linkage as characteristics of all sort of narrative and procedural discourse, but non- characteristics of behavioral and expository discourse which have instead logical( including topical) linkage. Likewise, we can look to narrative and behavioral discourse for lines of agent refrence( or, to speak more broadly). Participant refrence while in procediral and expository discourse this feature is absent. ( Procedural discourse is goal or activity focused, while expository discourse has theme rather than participants) 5. Narrative Discourse Bal ( 1997) cited in Fairclough(2003 ) approaches the analysis of narrative in terms of an anlysitical distiction between: The faula, story ( this distiction originates in Russian formalism). And narrative text. The fabula is the material or content that is worked into a story, a series of logically and chronologically related events. The story is a fabula that is presented in a certain manner, this involves for instance the arrangement of events in in asequence which can be different from their actual chronological order, providing the social agents of actual events with distict traits which transform them into characters and focalizing the story in terms of partcular points of view. The same stoy can appear in a range of narrative text, texts in which a narrator realated the story in particular medium for instance a story in coversation, a radio news story, a documentary, or a film. Page | 12 Narrative discourse is the easiest discourse to acquire. A narrative discourse is a stotry told to entertain the listeners, and sometimes to teach social mores ( Ba’dulu, 2007) There are at least three varieties of narrative discourse. The easiest one to find is legendary narratives, folktales told; tales told so often that everyone known them. The second kind of narrative, and the most valuable kind of, is the narration of past events in the speaker’s life or family. Here we get account of the time I (someone) get lost or hurt badly, or got denounced before the law; what happened when we moved o got married, or went to school, etc. The third kind of narrative is an episodic narrative; the story of a tip, for example, where there is not one ovearall plot but a series of scenes, each with descriptive materal and a few events. After one scene, the action goes on another palced and another scene Contenwise, narrative discourse do not consist of only narratio. Most culture like to have the narration broken up by quoted convesation. The array of a culture lof a narrative discourse is follow: Narrative discourse = + Title + Aperture: sent/par/cl + stage: Par/dise/sent + Narrative episode: par/ dise/sent + Narrative peak: par/disc/sent + Narrative Post Peak: Par/ disc/sent + Closure: sent/par + Finis: cl/sent phr. : Read: A narrative discourse consist of the opotional title shot filled by a clause, sentence, or phrase followed by the optional aperture slot filled by sentence, paragraph, or clause, the optional stage slot filled by a paragraph, discourse, or Page | 13 sentence, the obligatory narrative peak slot filled by paragraph, discourse, or sentence, the optional closure slot filled by a sentence or paragrph, and the optional finish slot filled by aclause, sentence, or phrase. 6. Paragraph-Level Structures A paragraph is a cluster of sentences held together by a single theme or setting and organized according to some pattern ( Ba’dulu, 2007). Or, looking at a paragraph, from the larger perspective of discourse level, it is a small chink of discourse that function as a single consituent, Paragraph in written English are usually set up on ortographfic- appereance criteria as such as on structure. In fact, some writers can write without forming structurally well-formed paragraph, and have their text broken into paragraphs two or three inches a long, rather arbitrarily. Paragrpah boundaries in narrative discourse are marked by a change of activity, time, place, and cast of participants. They may be marked also by special sentence introducers, recapitulation, sentence time margin, location margins, and sentence topics. Some times, in the absence of clear gramatical signals, paragraph boundaries have to be ditermined by the patterens of inter sentence relationship, the scripts or frame of paragraph structure. 7. Narrative Paragraph Narrative paragrphs are similar to narrative discourse and to the narrative sequence sentence. They encode sequences of events in narrative time ordering. The stucture of a narrative paragraph is given below: Page | 14 Narrative paragraph = + setting sent/ par + buildup(s): sent/par + buildupp: sent/par + terminus: sent/ par Read: A narrative paragraph consist of the optional setting slot filled by a sentence of paragraph followed by the obligatory buildup(s) slot filled by a sentence or paragraph, the obligatory buildup- peak slot filled by a sentence or paragraph, and the optional terminus slot filled by a sentence or paragraph. The component of setting is usually a sentence or paragraph containing descriptive clauses, action clauses, existence clauses and the like. The exponent of the setting is not a pat of the story line and doesn’t encode any action of the narrative. The exponent of the buildups are narrative or sentence or compound, alternative, or repetation sentences or paragraphs. They endoce events in the story line. Buildup-p is the climatic, peak bulidup. Since it is on paragraph level, it is ot as high a climax as in the climax at a narrative discourse. The teminus is conclution to the paragraph and is usually brief or absent. It encode evaluation material, subsequent secondary events. Quatation sentences may expound narrative build- ups. Such quotation sentence may be quite important an narrative structure, or important to narrative style. In narrative paragraph, some of the build-ups may be expounded by an explanatory paragraph. The text of explanatory paragraph would expound the buildup by itself, but it has some explonatory sentence following it, so the wouldbe exponent of the buildup plus the explanatory sentence constitute an explanatory paragaph that expounds the buildup. And some times, an exposition Page | 15 tagmeme in an explanatory paragraph is expounded by a narrative parragraph which served to reinforce the text of the paragraph. 8. Events and Participants in Discourse To analyze discourse from a linguistic point of view reuires a starting point. The work of Gleason and his group has provided such an entering wedge. The distiction among different kinds of information is most obvious in narrative discourse as opposed to the procedures, explanation, exhortations of Longacre’s typology. Procedure, which like narrative are based on the nation of temporal sequence, are the next most productive. a. Events The first distiction made in the analysis of discourse events and non events. In Garner, the halfback, made six yard aaround end we are told two kinds of things: a particular persson is named Garner and is a halfback( neither of which is an event). Some times entire paragraph are devoted to non- events, as in the description of a scane or a person. Gleason, who pionered in explaining the difference between events and non events, pointed out that different languages approach the time sequences between neigboring events in different ways. In Kate, for example, events that are continguous in time are distinguished from those that are separated by lapse may be long or short; but if it is noticable in terms of the steam of notion of the narrative, it must be mentioned. We can envinsion logical possibilities for temporal relation between two events that are reported as a siquence. If we take A as the earlier of the two events and B as the later, we can distinguish several cases: A finishes significantly long Page | 16 before B begins. A finishes by the time B begins, A finishes just as B begins, and A does not finish by the time B begins. In the last case we mibht have to spcify further whether A ends during B, A ends when B ends or A contains all of B and continues on after B is finished. Robert Litteral applied the matematical notion of topology the linguistic treatment of time. He notes first that when time is handled by language, it is measured only rarely. It is also characteristic of the linguistic handling of time that the boundaries between events ae rarely clear cut. Litteral takes the events as subas for the topology of the time line. This means that each events that is in the narrative is presented by an open set are a base for the topology that expresses the linguistic organization of time. Another kind of sequences between events is what Roland Husman has characterized as tigh vs. In Angaataha, a language of the eastern Highlands of Papua New Guinea, Huisman reported two kinds of sequencing temporal and logical ech of which may be tigh or loose. The time sequence of a narrative is rarely expressed as though events simply followed one another like beads on astring. Instead, There is usually a grouping of events into smaller sequences; then each of these smaller sequence as unit is put together with pther sub- sequences from the herarchical groupng of linguistic elements, Litteral has eliminated the nation of temporal sequences as one of several rhetorical relations. Instead he has moved temporal sequences into the area of refrences. Another grouping principle that partition events in a single temporal sequence could called the principle of common orientation. A sequence of events Page | 17 in distinguish from a later part of the same time sequence in that all the actions in each part involve uniform relation among their participants. Beside common setting and orientation, some event sequences appear to be grouped together by the law that relate to plot structures. Not all events, or course, are sequence. Language is capable of communicating of fork action as in you take the high road and I’ll take the law road, which is not a descriptive of sequence of event. In other cases a language may mark certain stretch within which sequence is irrelevant. b. Participants The information that identifies the participants in an event not only links participants to event, but also links one mention of a participant with other mention of the same participants. It obeys rule of its own in addition to combining wit event information. The role ranking gives a scale of relative involvement in an action, from deliberate involvement expressed by the agent, to being acted upon in the patient and instrument, and from there on down to zero involvement. This ranking might make it possible to divide the things mentioned in a text into those that never appear in the more active semantic role, the props, and those that do, the participants. The distinction between participants and props does seem to be related to plot, possibly in the sense just mentioned. That is, even if activity is not relative to the role system as such, yet it take place. A forth possibility for distinguishing between participant and props is suggested by the study of orientation system. If we assume that changes in the orientation of participants to ward sections are systematic than any elements that Page | 18 would break the regularity of orientation patterns if considered as participants are probably props. This notion combines two things; the relative involvement in the more comprehensive categories, and relative involvement in the more comprehensive categories of plot. Reference to whom and what is involved in an event is particularly independent of the means used to identify each referent. Participants are referred to as individuals or groups. Reference to individuals presents relatively few problems. Group reference, on the other hand, take a number of forms. Sometimes reference shift during the course of a text. There are three kind of shift: introduction and deletion. recombination, and scope change. Introduction and deletion involve expanding and contracting reference by adding or subtracting individuals from a group. Where there is a shift in the spatial view point from which events are reported there may also be a shift reference. When a narrator has been speaking as though he was omniscient and knows everything that goes on both inside and outside the heads of the participants, he may shift, for example, to presenting events as a certain one of the participants sees them, or vice versa. When he shifts, what at first he had treated as reference to individuals may change to reference to groups or one pattern of grouping may be replaced by another through margin and splitting. The basic problems in identification are first, establishing reference sufficiently well that the hearer is clear about who is being talked about, and Page | 19 second, informing or maintaining it sufficiently well to keep the hearer from becoming confused. From this point of view of discourse studies the striking thing about the identification information that goes with participants in events is the different grammatical forms that are used to communicate that different kind of information. Whereas events tend to be communicated by independent verbs in most languages, transform from underlying predicate whose role sets include nearly anything, identification tend to involve the embedding of sentences. Identification is also maintained through the use of anaphoric elements. Pronouns are common of maintaining identification. How efficient they are depends on the richness of categories off the categories of appropriateness of reference that are available within the pronominal system. Identification reference is closely enough related to pronouns that the two are sometimes discussed together. From the point of view identification, however, it is important to notice that the categories that appropriateness of reference for inflectional system are never more finely divided than those of the pronouns with which they may stand in cross reference. 9. Non-Event in Discourse a. Setting Where, when, and under what circumstance take place a separate kind of information constitute called setting. Setting is important in the study of discourse not only because it characteristically involve distinctive grammatical construction Page | 20 like locative, but also because it is a common basis for segmentation of sequential text into their component part. It is tricky to distinguish setting from the range role. Either may, for example, take the form of a locative like a prepositional phrase. One text that seems to work in a number of languages is the test of spare ability Setting in space is frequently distinguished from settings in time. All languages probably have the capability for defining a spatial setting by description. Spatial setting may redefined during the course of a text either by describing where each new setting is located, as seems normal in English, or by a relative redefinition that takes the most recent settings as its point of departure. The scope of a spatial setting may be broad or narrow. Settings in time are equally important. Temporal properties inherent in particular action. Whether an action follow it predecessor immediately or after a lapse, whether its effects are said to persist, all are dependent of general time frame work of narrative, just as the place where as action happens is independent of those elements of location ( rang) that are an integral part of the definition of the action. Descriptive definition of time usually with reference to some kind of calendar reference. Another kind of time definition makes use of reference to memorable events. This can shade off into a calendar system of its own in the case of dynastic or definitions of years by outstanding events. Page | 21 b. Background Some of information in narrative is not part of the narrative themselves, but stand outside them and clarifies them. Event, participant, and setting are normally the primary components of narrative, while explanation and comments about what happens have a secondary role that may be reflected in the use of grammatical patters Much of the secondary information that is used to clarify a narrative (called background for convenience, even though, the form may be misleading for non- consequential texts when explanatory information could be thought of as being the foreground) has a logical sounding structure, frequently tied together with words like because and there. It is an attempt to explain. It has this explanatory from even when the logic in it invalid or when it falls a short of really explaining what it purports to explain. Explanations, either as secondary part of narrative or as a central theme of text, often involve premises that the speaker feels are generally accepted and there for can be left unsaid. Some times what is unstated brings concentrations to linguists from another culture who is not yet in a position to supply the missing pieces of the argument The handling the structure of explanations actually sheds light on the depth and sensitivity of the speaker’s of who hear estimate who hearer is. Because even in cultures where nearly all parts of an explanation or argument are assumed, if the hearer make it sufficiently clear that he doesn’t follow, most speakers will restate themselves in an attempt to make up for his lack of understanding. This is less likely o hold in relatively homogeneous and isolated cultures, where many of Page | 22 life’s activities depend upon the assumption that everyone shares the same fund of information. c. Evaluation Not only do speakers report the state of the word: they also tell they feel about it. The addition internal feeling to other information (which is not the same as a simple reporting of what one’s internal feeling are ) involves specific modes of linguistic expression. Often evaluation are imputed to hearer or to the other people referred to in the discourse. Any participant in a discourse can be assumed to have his own opinion of things, and the speaker may feel that he knows what those opinions are sufficiently well to include them. There is, however, a restriction that is pointed out in manuals of short story writing. Another kind of evaluation is that of the culture within which the speaker is speaking, the conversation of the society he represents. Not everything in a discourse has to be evaluated. For this reason, it is useful to recognize that scope of an evaluation statement. It may be global, embracing an entire discourse, if so, it is likely to be found either at he beginning as an introductory statement that tells why the rest of the discourse is being told, or at the end as a moral to be story of the tag line in table. Evaluation bring the hearer more closely into the narrative; they communicate information about feelings to him that goes beyond the bare cognitive structure of what happened or what deduction is to be made. In conversation, and even monologues, the hearer may be pressed to give his own evaluation: what do you suppose they took that? Page | 23 Evaluative information shades off into background or even into setting in cases where it serves to build up the psychological tone of series of events. d. Collateral Some information in narrative, instead of telling what did happen, tells what did not happen. It ranges over possible events and in so doing sets off what actually does happen against what might have happened. Collateral information, simply stated, relates non-events, By providing a range of no-events that might take place. It heightens the significance of the real events. The information about what actually does happen, then, may take several forms. If none of the collateral expressions give what really happened as one of the alternatives it must be stated as distinct event. If it was mentioned ahead of time, however, then it is not necessary to repeat the content that was mentioned as part of the collateral, but only to affirm which of the possibilities took place. 10. The Speaker and Hearer in Discourse Both the form and the content of any discourse are influenced by who is speaking and who is listening. The speaker-hearer-situation factors can be represented in linguistic theory of performative information There are, however, restrictions on per formative utterances. They must be in the first person and present tense. Certain per formative are quite common and are free of special limitation on their use. The recognition of implicit per formatives behind commands, question, and statements, as well as explicit per formatives, paves the way for linguistic handling of situational factors in Page | 24 discourse. Specially, it gives a place in linguistic analysis for what are conventionally known as deictic (pointing) elements like” this” and “that” or “here” and “ there”, and for person categories like ”one” and “ you”. In the case of persons ( and for that matter, object ) the recognition of the speaker-hearer axis in communication is the basis for assignment of person categories. This seems trivial or obvious for a discourse that has a single per formative. Per formative are pertinent in the identification of participants in other cases besides direct discourse, but in a different way. Indirect discourse, person assignments are taken from some per formative more remote than the one that dominates the statement immediately; that is, the one that constitutes the nearest verb saying that dominates direct discourse higher up the three of questions. This show up if we paraphrase the example just given in such a way as to show the per formative elements. In addition to the identification that relates to performatives, the there are other less easily recognizable factors whose effect can be seen in the outer from of language and that find their place in the conceptual scheme of linguistics by virtue of their relation to per formative. Here, first of all, is where the speaker’s entire image of himself as a person is accessible to the linguistic system. The per formative element not only serves to relate persons to the discourse, but also sets the zero point for time reference. Page | 25 11. Kinds of Information in Discourse a. A Work Sheet The idea of different kind of information in a text is ore easily put to use if there can be a display of text that lay out each kind of information in a way that can be seen at glance. Event Figure. 11. 1. A Blank Thurman Chart The vertical columns on the chart correspond to the various kinds of information distinguished in the text: events, identifications setting, background ( which to save space includes both explanations and evaluation), collateral, and per formative. To keep the chart from being crowded, we can use the conversation that information of particular kind begins under the corresponding heading, but Page | 26 may be carried as far to the right as needed; this is more convenient that trying to squeeze everything into narrow vertical columns The parallel vertical lines are for the participant, one line per participant. For each event in line is drawn from the lexical elements that represent the event to the vertical lines that represent the participants in the event. Where identification is given for the participant lines are also drawn from the other side to show which identification belongs with which participant. The most comfortable working format is to match a Thurman chart with a page of text. The text is written out, double spaced, at about one clause per line. Some clause more than one line, and it may not be clear exactly what clause is until after the analysis is finished; but in general the clause is convenient chunk to work with. The next page is fastened to the Thurman chart with the text on the left and the chart on the right. b. Span Analysis From the Thurman chart is possible to go on to another level of abstraction further removed the text itself, namely the plotting of spans. Spans represent stretches of text within which there is some kind of uniformity. Certain kind of uniformity have already tured out to be useful for characterizing discourse structure in several languages. If we take a page and write clause numbers on the Thurman chart, though more closely spaced, we have a framework for a plot of the spans in a text. Each span is represented by a vertical line, Sometime broken by a horizontal line or Page | 27 interspersed by symbols. This representation makes it possible to put many spans on a single page so that they can be compared with one another. Setting spans are the most obvious ones for to look for in narratives. One vertical line indicates all the actions that take place in a single spatial location, and another vertical line indicates all the actions that take place in a single time sequence. A horizontal line that shows where a spans is broken is useful for matching spans across the page, If a time index back up to repeat a sequence. Or if there is a resetting of the time of an action in terms of another hour o day, this starts a new time span. B. Conceptual Framework Discourse analysis is the study of how stretch of language used in communication meaning, purpose and unity for their users: the quality of coherence. Whereas discourse itself may be defined as language that is doing some job in some context, i.e., in some context of social situation. Discourse in communicative context implies that discourse is primarily language; however, it is not language that exist independently, apart from the daily life of its speakers. Discourse is term in linguistic to revert a continuous stretch of ( especially spoken) language larger than a sentence- but within this broad nation, several different applications may be found. A narrative, discourse is a story told to entertain the listeners, and sometimes to teach social mores. Paragraph boundaries in narrative discourse are marked by change of activity, time, place, and cast of participants. Page | 28 A narrative discourse consist of seven important components: events, identification, setting, background (which to save space includes both explanations and evaluation), collateral, and per formative. The first distinction made in the analysis of discourse events and noevents. The information that identifies the participants in an event not only link participants to event, but also links one mention of participants with other mention of the same participants. From the point of view of discourse studies the striking thing about thing about the identification information that goes with participations in events is the different grammatical form that are used to communicate the different kinds of information. Where, when, and under what circumstance called setting. The component of the setting is usually a sentence or paragraph containing descriptive clauses, existence clauses and the like. Background is some of information in narrative which is not part of the narratives themselves, but stands outside them and clarifies them. Often evaluation are imputed to the hearer or to the other people referred to in the discourse. Another kind of evaluation is that of the culture within which the speaker is speaking, the conversation of the society he represents. Some information in narrative, instead of telling what did happen. Collateral information, simply stated, relates non-events to events. Both the form and the content of any discourse are influenced by who is speaking and who is listening. The speaker-hearer-situation factors can be represented in linguistic theory of performative information. Page | 29 The idea of different kind of information in narrative text is more easily put to use if there can be display of text that lays out each kind of information in a way that can be seen at a glance. From the Thurman chart it is possible to go on to another level of abstraction further removed from the text itself, namely the plotting of spans. The conceptual framework of this research as follows: Narrative Discourse (Text/written Form Analyzing the Main Part of the Story Analyzing Kinds of Information in the text through a work sheet (Thurman Chart) Analyzing the Structure of the text Page | 30 CHAPTER III METHOD OF THE RESEARCH A. Research Design The design of this research uses qualitative research (Marshal and Rosman, 1995). Qualitative research method have become increasingly important modes of inquire for the social science and applied field. Qualitative research is the collection data, analysis, and interpretation of comprehensive narrative and visual data in order to gain insight into a particular phenomenon of interest. The purpose of qualitative research are to analyze feel of story with finding or to know setting background, event, collateral, performative, evaluation and to identify dependent clause and independent clause B. Sources of Data Talking about source of data, this data is taken from the book of More Favourite Stories from Indonesia, that is the story of The Clever Pottala. The author this book is Marguerite Siek and the second printing in 2005, and published by PT. Rosda Jayaputra . C. Data collection The procedures of collecting data in this research is observation the book where the writer look for the book that is suitable to be analyzed and making Page | 31 fieldwork. Fieldwork includes field note, the writer will collect writing several note that relate to this analyzing, besides, the book that relate to this analyzing. D. Data analysis Data is taken from the story of The Clever Pottala by observation. The data is analyzed based on the story, to find or to know dependent clause and independent clause in sentence, setting, background, evaluation, event, collateral and performative. Page | 32 CHAPTER IV FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION A. Findings 1. The Narrative Text The Clever Pottala Once upon a time there was a headman lent a sum of money to a peasant called Pottala. When the time came to return the money, the headman came to visit Pottala and asked him for the money. Pottala had no money. He said to the headman, “I haven’t got the money yet. Somebody else has borrowed it from me. Please wait a few more days, so that I will have time to collect what people owe me.” The headman agreed and said that he would return in four day’s time. But when the fourth day came, Pottala still did not have the money. He decided to treat the headman. Early in the morning, he went to the river and caught a fish. He boiled the fish in a pot of water and when the soup was ready, he took out the fish and put an iron axe into the pot instead. When the headman arrived, Pottala politely invited him into the house and served him a bowl of the delicious fish soup. “Hm, that’s very nice,” said the headman. “What did you make the soup with, Pottala?” “Oh, just this axe,” Pottala said pointing to the axe in the pot. “Just…this axe? Nothing else?” Page | 33 “Nothing else. This is a soup-axe. Would you like another bowl? I made plenty of soup.” After the two men had finished the soup, the headman asked for his money. “I haven’t got the money. Please give me some more time, sir,” said Pottala. “You know what,” said the headman, just pay me with that soup-axe.” Pottala agreed, and the headman went happily home with the axe. He gave the axe to his wife and told her to make soup with it for the evening meal. His wife obeyed, but although the axe was boiled for hours and hours, the water remained just water. The next day, the headman returned the axe to Pottala. “You lied to me, Pottala,” he said angrily. “This is an ordinary axe. It can’t make soup.” “But sir, you saw yourself that there was only this axe in the pot yesterday, and you liked my soup,” said Pottala. “I don’t want your axe anymore, Pottala. Give me back my money,” said the angry headman. “I haven’t got your money yet, sir. Please give me some more time,” answered Pottala. The headman agreed to give him another three days. After three days he came back to Pottala’s house. “Where’s my money, Pottala?” he asked. “Please sir, come in. I’m just going to prepare my lunch. Why don’t you eat with me?” said Pottala. The headman agreed and climbed up onto the verandah. Then Pottala took a blowpipe and pointed it to the sky. “What are you doing?” asked the headman. “I’m shooting a wild duck for our lunch, sir,” answered Pottala. “But there’s no wild duck to be seen,” said the headman. “They’re flying over the sea, sir. This blowpipe can shoot as far as the sea,” said Page | 34 Pottala. He pointed it once more at the sky and blew as hard as he could. “Let’s go into the kitchen now. The duck will be on the table,” Pottala said to the headman. Together they entered the kitchen and sure enough, there was a wild duck lying on the kitchen table. “There she is,” said Pottala. “This is a special blowpipe. Not only can it hit a duck far away, but it brings it back to the kitchen, too.” “Oh, let me have that pipe, Pottala,” said the headman. “Give me the blowpipe and you need not give me back the money.” “Well, if that’s what you wish, sir, of course you may have the blowpipe,” said Pottala. The excited headman went home with his blowpipe. He was so impatient to try it out that he did not want to wait for Pottala to cook the wild duck. As soon as he arrived home, the headman aimed the blowpipe at the sky and blew in it. Then he ran to the kitchen. But to his great disappointment, there was no duck on the table. He ran back to the verandah and blew and blew till he was red in the face. But still no duck appeared. The whole day, the poor man ran to and from his verandah to the kitchen, until he fell exhausted on the floor. And still no duck appeared on the kitchen table. Then the headman understood that again he had been cheated by Pottala. The next day, he went back to the peasant and demanded his money. “But sir, I’ve paid you with the blowpipe,” said pottala innocently. “Here’s your blowpipe. I don’t want it. Give me my money!” shouted the headman angrily. “You’ve cheated me Pottala!” Page | 35 “But sir, you saw yourself that I killed a duck with it yesterday,” answered Pottala. “Give me back my money!” “Please sir, I haven’t got the money yet. Can you give me some more time?” Although he was angry, the headman agreed to give Pottala another two days to find the money. This time, Pottala caught a dog and put a silver coin under its tail. When the headman came and asked for his money, he said, “Sir, I haven’t got the money yet. The people who bought my rice and fruit have not paid me yet. But I was given a rather special dog who might be able to help a bit. Would you like to see this dog, sir?” “Yes,” said the headman, “just bring him here.” Pottala took the dog out of the house and put him on a mat. He stroked the animal and said, “Come now, give me a coin.” The dog wagged his tail and Pottala took the silver coin from it. “There you are, sir,” he said, offering the coin to the headman. “Can I give this coin to you? The dog only gives a coin at a time.” The headman was delighted. “Oh, Pottala,” he said, “give me that dog and you need not pay me the rest of the money.” “As you wish, sir,” said Pottala obediently. So the headman took the dog home. At home, he tied the dog under his bed and waited impatiently for several hours. Then, when he thought the dog had rested long enough, he stroked his back and said, “Come now, give me a coin.” The dog wagged his tail happily, but that’s all it did. And again the headman understood that he had been tricked by the clever peasant. Page | 36 “That’s it! Now I’m going to arrest him!” he shouted. He ordered two guardsmen to go to Pottala, put him in the bag, and throw him into the river. The men went to Pottala’s hut and carried out his orders. Fortunately, Pottala had his knife with him, and he was thrown into the river, he cut a hole in the bag and swam to safety. He left his village and went into the forest where he opened a new field. After some time, when his field had grown some sweet potatoes, he went back to the village to sell them. At the market, he met the headman who stared at him at amazement. “Pottala! I thought my guardsmen threw you into the river,” he called out. “Yes, sir, I was thrown into the river,” answered Pottala, “but when I reached the bottom, the water folk rescued me. I lived with them for a while, but I got homesick for my village, so I asked them to take me back up to land.” “Is it beautiful down there?” asked the headman curiously. “Oh, it’s the most beautiful place one could ever see,” answered Pottala. “Then put me in a bag and throw me into the river, because I want to see the place where the water folk live,” said the headman. “As you wish, sir,” said Pottala. He put the headman in a bag and threw the bag into the river, where the headman drowned. Pottala went back to his field in the forest and lived peacefully for the rest of his life. Page | 37