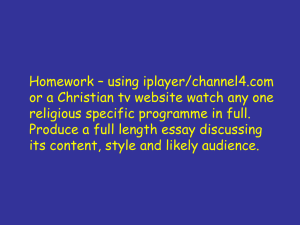

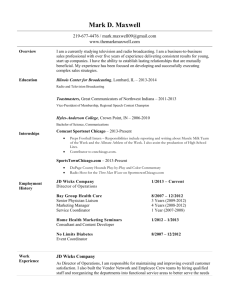

Background

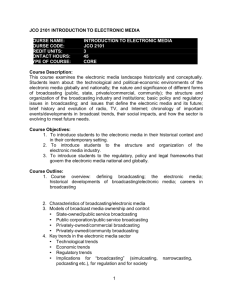

advertisement