Spectrum article - James Madison University

advertisement

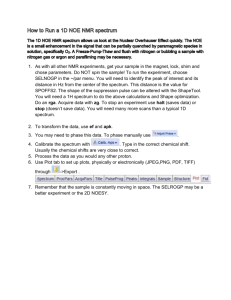

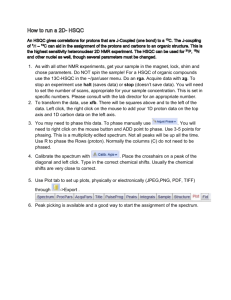

Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 1 1 The Spectrum of Teaching Styles- Revisited 2011 2 Michael Goldberger 3 James Madison University 4 The Spectrum of Teaching Styles was introduced over forty-five years ago when the first 5 edition of Teaching Physical Education (Mosston, 1966) was published. As we approach the 6 semi-centennial anniversary of its inception, and as a new generation of teachers is being 7 introduced to the Spectrum, we thought a retrospective might be timely. In this article we 8 provide a brief history of the Spectrum, discuss several of the key refinements since its inception, 9 and, in closing, we respond to a commentary about Spectrum theory by two European colleagues 10 (Sicilia-Comacho & Brown, 2008). We invite those interested in learning more about the 11 Spectrum to visit our website at www.spectrumofteachingstyles.org. We are also pleased to 12 announce that a special edition of the book Teaching Physical Education is available for 13 downloading at no cost at our website courtesy of the Spectrum Institute for Teaching and 14 Learning. 15 16 The Spectrum of Teaching Styles – A Retrospective What is the Spectrum of Teaching Styles? Over the years we have heard all the following 17 descriptions- a framework, a paradigm, a basic structure, a model, a schema, a system, a theory, 18 and more. It is, we suppose, all of those things, however for the many teachers we’ve worked 19 with over the years the Spectrum is first and foremost a tool that has become an integral part of 20 their daily teaching routine. It is a tool that helps teachers better harmonize their intent and 21 action. Just as a compendium of topical information guides the teacher in selecting content, the 22 Spectrum provides a comprehensive array of behavioral approaches, or as we call them, teaching Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 2 23 styles. In our experience we have found that no teaching style is inherently better than another. 24 We have found that each teaching style is either more or less appropriate given the purposes, the 25 situation at hand (including the learners), and the kind of learning context. 26 In describing the Spectrum we like to use the word ‘elegant’ because it is, at the same 27 time, deceptively simple, logical, and straightforward, and yet complex, elusive, and knotty. 28 Spectrum colleagues from many countries have been studying and working with the Spectrum 29 for many years and for us it continues to both create and unlock mysteries about teaching and 30 learning. Who was it that observed that "teaching is as mystifying as life itself”? Although we 31 agree with that characterization, the Spectrum has provided an entrée into and an anchorage 32 within the fascinating world of teaching and learning. It provides an entrée by offering a 33 common perspective, a number of undergirding concepts, and a functional language we can all 34 use. For the sport pedagogy scholar, it serves both as an organized repository for knowledge 35 about teaching as well as a catalyst for generating new pedagogic research questions. The 36 Spectrum cannot solve all the problems of the teaching profession, but we believe it can help by 37 providing all involved in the teaching/learning enterprise with a common perspective and 38 language. 39 During the early 1960’s a young physical education professor at Rutgers University in 40 New Jersey was asking some pretty interesting questions about teaching. Is teaching an art, a 41 science, or both? Can a teacher, regardless of her/his personality, learn to teach effectively using 42 a variety of teaching approaches? What is the relationship between teaching and one’s 43 educational philosophy? How many different teaching approaches are there? Is there a finite 44 number? What is the relationship between teaching behavior and learning outcome? Is there a 45 unified theory connecting all these ideas? Dr. Muska Mosston was that professor. Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 3 46 _____________________________________________________________________________ 47 Place Mosston photo about here 48 _____________________________________________________________________________ 49 Mosston loved working with his university students as much as he loved working with 50 children in schools and camps. He also loved playing with ideas. He invented playground 51 equipment and models made out of clay and wire could be found around his home and office. He 52 invented games, contests, and physical challenges for his students. His groundbreaking work 53 with ‘developmental movement’ provided an innovative model for the study of human 54 movement. 55 During the early 1960’s Mosston had his own television program on Saturday mornings 56 on WCBS-TV in New York City. The weekly program was carried for several years under two 57 titles, ‘Having a Ball’ and ‘Shape Up’. The half-hour sessions were broadcast live, these were the 58 days before video-tape. Mosston would lead a group of a dozen or so children through a series of 59 physical activity sessions demonstrating the teaching theories he was developing at Rutgers. 60 Because the sessions were not rehearsed, the children responded extemporaneously. There were 61 some magical moments of innovation and inspiration during those sessions. The program’s 62 producer/director, Ed Simmons, described his role as a ring-master as he tried to anticipate and 63 follow Mosston’s and the children through their paces. Most of the sessions were not recorded 64 but, luckily, several were saved using a process called kinescope. 65 Mosston was developing a national reputation as a non-conformist thinker and 66 charismatic speaker on the topic of teaching physical education. He traveled extensively while 67 still teaching at Rutgers. One day, while back on campus, one of his university students, out of Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 4 68 frustration in trying to replicate his master’s teaching approaches, said to him, “Professor 69 Mosston, I can’t be you!” After a pause the student continued. “Furthermore, I don’t want to be 70 like you.” This encounter affected Mosston like a splash of cold water in the face. He 71 recognized the dilemma and turned his attention away from honing his own skills to 72 conceptualizing a vision of teaching that would include, but that would also go beyond, his own 73 teaching repertoire. In our view Mosston’s greatest contribution to teaching was providing the 74 particular perspective from which the Spectrum evolved. That perspective was captured in the 75 simple premise- ‘teaching behavior is a chain of decision-making.’ The premise was that all 76 teaching and learning behavior was the result of decisions previously made. What emerged from 77 this premise was a continuum of behavioral approaches, all undergirded by the decision-making 78 premise, that ranged from command to discovery. 79 For the next thirty years the Spectrum was foremost on Mosston’s agenda. After leaving 80 Rutgers he established the Center on Teaching, a federally funded project designed to further 81 explore Spectrum theory, develop training materials, and conduct implementation studies. Over 82 the next two decades Mosston, Through the 1980’s Mosston spent a great deal of time overseas, 83 and governments, 84 In 1994, at the age of 68. Muska Mosston passed away in his home in New Jersey. 85 86 All Spectrum work, both theoretical and practical, emanates from and rests upon this 87 simple premise. This premise provides us all, teachers, teacher educators, teaching researchers, 88 administrators, math and science specialists, art specialists, physical activity specialists, parents, 89 and students with a common perspective about teaching and a common language which allows Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 5 90 us to communicate objectively. Qualifiers such as “in my view” or “in my opinion” are typically 91 not necessary within a Spectrum discussion. The Spectrum makes no judgment about any 92 teaching approach but rather identifies its position along this decision-making continuum. The 93 Spectrum provides reference points, so that the location of any teaching approach can be 94 identified. Those who know the Spectrum can observe any teaching/learning encounter and can, 95 with a good degree of accuracy and reliability, agree on which decisions were made by the 96 teacher, which decisions were made by the learner, and which decisions were not made by 97 anyone, and thus can identify which teaching style was being used. As best as we can recall, the 98 following describes Mosston’s thinking as he developed the Spectrum in the early 1960s. Once 99 he settled on the decision-making premise, the next steps flowed smoothly. If teaching behavior 100 is a chain of decision-making, what then are the decisions that must be made in any 101 teaching/learning transaction? As many decisions as possible were identified, including big 102 decisions (like the subject matter to be taught- a content decision) as well as small decisions (like 103 should a whistle be used- a signal decision). Mosston then organized these myriad decisions into 104 a framework with three temporal sets: (a) pre-impact or planning decisions, decisions made prior 105 to the teacher-learner engagement, (b) impact or implementation decisions, decisions occurring 106 during the teacher-learner engagement, and (c) post-impact or assessment decisions, decisions 107 made after the engagement has begun. He called this framework the Anatomy of Any Style (see 108 Figure 1) and the Anatomy undergirds every teaching style. 109 110 Place Figure 1 About Here 111 112 Actual teaching styles emerged from the Anatomy by identifying who, teacher or learner, 113 makes which decisions. So, if the teacher makes all decisions, and the learner complies with the Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 6 114 teacher’s directions (the one decision the learner almost always has to make is whether or not to 115 comply), a style of teaching emerges that Mosston labeled the Command style. In this style, the 116 teacher provides very specific directions, including pace/rhythm and posture, and the learner 117 complies by performing as accurately as possible striving to achieve precise performance. Did 118 Mosston “invent” Command style? No, but he clarified it and placed it within the broader 119 context of the Spectrum. 120 Some people find the word ‘command’ uncomfortable, conjuring up an image of a 121 domineering leader and exploited followers. Labels, although necessary, can be misleading. 122 Mosston attempted to avoid this pitfall by identifying each style simply by a letter, so the 123 Command style was labeled Style A, the Practice style was Style B, and so forth. One must not 124 take any label literally and control one’s rush to judgment when considering the utility of any 125 teaching style. In selecting a teaching style it is a matter of deciding which approach would best 126 provide the learning environment most conducive to the objective(s) at hand. For example, if 127 one is teaching dicing in food preparation, or how to pull onto a freeway in driver education, or 128 performing an appendectomy in medical school, or how to print letters in first grade language 129 arts, or how to shoot an arrow (archery) in physical education, an episode in the Command style 130 might be an effective approach to get things started. 131 A more graphic example of a situation suggesting the use of the Command style involves 132 fire drills. A school that doesn’t have a fire drill policy, and/or that doesn’t have the children 133 master this routine, is likely negligent in terms of basic safety practice. Learning to respond to a 134 fire drill is a Command style activity. To provide a less dramatic example, but one that is 135 perhaps more educationally relevant, the Command style can be observed when watching a 136 marching band. Of course there is a lot of preparation the band goes through but when the leader Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 7 137 signals the start, and everyone in their uniforms respond in a manner decided upon by the 138 director (pre-impact), this is an example of the Command style in action. Again, let us be very 139 clear, the Command style, with the teacher directing the learner what to do and the learner 140 following directions implicitly, is not new to pedagogy. It has existed throughout recorded 141 history. But what Mosston did was to identify its place along the Spectrum of Teaching Styles. 142 Finally, anyone watching the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympic Games, with the 143 incredible precision of the hundreds of participants, observed the power of the Command style. 144 Mosston thoughtfully shifted decisions from teacher and learner to form an array of 145 different teaching styles and thus the Spectrum evolved. At one end of the Spectrum is the 146 Command style. At the other end of the Spectrum is a teaching style in which the learner makes 147 all decisions, independent of others. This is the Self-teaching style. This style, outside the 148 confines of the regularly scheduled physical education class, is self-guided in all three sets of 149 decision --- planning, implementation, and assessment. An example of this might be a high 150 school student who chooses to go to the local community recreation center to participate in a 151 self-developed (based on knowledge learned in his school physical education program) weight 152 training program. 153 In our view, these two end styles (teacher makes all decisions and learner makes all 154 decisions) are universal. What alternatives do you have to those decision-making 155 configurations? The styles in between these bookend styles, identified by Mosston by 156 thoughtfully shifting configurations of decisions between teacher and learner to form different 157 teaching styles, were designed by Mosston (1966, 1981), and later refined with his colleague 158 Sara Ashworth (1986, 1994, 2002), are not universal in the same sense as the bookend styles. 159 The shifts along the Spectrum are Mosston’s conceptualizations. So, another person may come Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 8 160 along, Smith for example, and, using Mosston’s decision-making premise, s/he might identify a 161 different batch of teaching styles based on different decision making configurations. The Smith 162 Spectrum might have four styles or it might have 40 styles. Again, the only styles likely to be 163 truly universal are the two bookend styles. The styles that Mosston identified represent his 164 vision and his rationality and thus we identify this as Mosston’s Spectrum of Teaching Styles. If 165 others were to develop other models based on Mosston’s work, in our view, it would be 166 professionally honest to give Mosston the credit he deserves as the original designer/developer. 167 So, acknowledgments such as Smith’s Adaptation of Mosston’s Spectrum of Teaching Styles 168 might be an honest and appropriate identification, in our view. 169 In 1966, Mosston wrote the first edition of Teaching Physical Education and this book 170 introduced the Spectrum to the world. In this edition he identified eight teaching styles (now 171 there are 11) and he provided examples about how each might be used in teaching physical 172 education. Mosston provided a schema (visual) of the entire Spectrum, which attempted to 173 provide an overview (see Figure 2). The diverging lines were meant to indicate, we believe, that 174 in his view education should proceed from a dependent learner toward the target of an 175 independent learner. 176 177 Place Figure 2 About Here 178 179 180 Five Refinements The book is now in its fifth edition and while the Spectrum’s premise has stayed the same 181 and the idea of shifting decisions between teacher and learner to form different teaching styles 182 has remained unchanged, there have been a number of refinements. Let us highlight and discuss Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 9 183 five of them. These refinements emerged as Mosston, and later Ashworth and others, studied 184 and implemented the Spectrum over the past half-century. 185 Non-versus. 186 When the second edition of Teaching Physical Education was published in 1981, one 187 change was in the schema/diagram. In the revised Spectrum schema (see Figure 3), each 188 individual style appears to be of equal dimension. The size of the square representing Style A is 189 the same as Style B, Style C, and so forth. In contrast, the original Spectrum schema (see Figure 190 2), because of the two diverging lines forming a “cone” across the schema, it appears that the 191 styles on the left side are smaller, and by implication, of less value than the styles to the right 192 side. This is not what Mosston believed. He always believed in the power of each style to 193 contribute in unique ways. He never envisioned individual styles in opposition to each other. In 194 his view the styles were complimentary. In the preface to the second edition (1981) he wrote, 195 “The conceptual basis of the Spectrum rests on the NON-VERSUS notion. That is, each style 196 has its place in reaching a specific set of objectives; hence, no style, by itself, is better or best.” 197 (page viii). Those of us who knew him know how much he would have enjoyed the opening 198 ceremonies of the Beijing Olympics. He would have been in awe of the precision and would 199 have said something like, ‘Wow, the power of the Command style.’ But, he would never 200 advocate for an educational system dominated by the Command style (or any other style). There 201 is a lot any society must teach its younger generation and making the entire Spectrum available 202 to teachers, to make appropriate teaching style decisions, is likely the best we can do. In our 203 words, each style, because of the unique combination of teacher and learner behaviors it fosters, 204 creates a particular set of learning conditions. These particular learning conditions are either 205 more or less appropriate for supporting the learning objective(s) at hand. So, Mosston defined Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 10 206 and valued the Command style exactly the same way in both schemas. In the Command style the 207 teacher makes all decisions and the learner responds. The Command style is appropriate for 208 certain learning outcomes and inappropriate for others, based on the conditions it fosters. And 209 the same is true for each style along the Spectrum. But the first cone-shaped schema didn’t seem 210 to represent that view. It seemed to project a biased view of the relationship among the styles 211 and so it needed to be changed. 212 213 Place Figure 3 About Here 214 215 216 Landmark styles. As was mentioned above, the two teaching styles on either end of the Spectrum are truly 217 universal. Mosston developed other teaching styles along this decision-making continuum by 218 gradually shifting decisions between teacher and learner. A style shift resulted when a 219 significant new teacher-learner relationship and set of learning conditions emerged. For 220 example, Mosston identified a cluster of nine teacher decisions in the Command style that, if 221 shifted from teacher to learner, made enough of a change in learning conditions to be considered 222 a different teaching style. 223 In Mosston’s first edition (1966), eight teaching styles were identified in this logical 224 manner and thus made up the Spectrum of Teaching Styles. Over the years, through a process of 225 refinement, the number of teaching styles has increased to eleven. These eleven teaching styles 226 are referred to as “landmark” styles. Each landmark style has its own specific decision-making 227 Anatomy. But, within the Spectrum, what is it when you have a configuration of decision- 228 making that doesn’t replicate one of the landmark styles? These non-landmark styles are 229 referred to as “being under the canopy” of the nearest landmark style. In the revised schema, the Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 11 230 vertical lines between styles were replaced with segmented lines (see Figure 3). This was meant 231 to illustrate that decisions flow between styles and the separation is permeable and that styles are 232 not discrete. Are landmark styles better than non-landmark styles? If a non-landmark style is 233 selected thoughtfully for an episode, with the realization that it will create learning conditions to 234 satisfy a deliberate learning intent that are different from the landmark style, it might be very 235 appropriate for the situation at hand. Safety, equipment, facilities, and logistics are reasons for 236 not shifting certain decisions. Nevertheless, our observation is that the best way to get the full 237 impact of landmark styles is to employ them as they were designed. The insistence on being 238 clear with regard to whether or not an episode is landmark or under the canopy of a style has to 239 do with accountability. As in any quasi-scientific endeavor, clarity and precision are critical in 240 understanding the Spectrum and its implications. 241 242 In her book Teaching Middle School Physical Education (2003) Bonnie Mohnsen wrote: 243 244 245 246 247 248 249 My own teacher training in the 1970s primarily taught me simply to explain and demonstrate motor skills to students. I learned to follow this with having everyone practice the same skill simultaneously in the same way and to give students feedback afterward. As I visit classes across the United States today, this is the same strategy I still observe in the majority of classes. (p. 129) The vast majority of physical education classes we’ve observed over the years fall “under the 250 canopy” of the Practice style. We are not critical of this because we feel if the Practice style 251 were the only style used, and if it were used well, certain goals of physical education would be 252 achieved more consistently. The Practice style, with its various configurations/formats, has been 253 found to be a superb approach for basic motor skill acquisition, particularly with larger groups. 254 If learning motor skills was the only goal of physical education, using formats of the Practice 255 style almost exclusively could make sense. However, given the variety of important goals in 256 American education, and the differing circumstances teachers find themselves facing, we believe Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 12 257 the more comfortable and competent a teacher is in using a variety of pedagogical approaches 258 available (including different teaching styles) the more effective s/he could potentially be. The 259 concept of ‘mobility ability’--- the ability to easily move from style to style as circumstances 260 dictate --- is one we wholeheartedly endorse. 261 It is rare in our experience to observe certain styles used routinely in mainstream physical 262 education classes. For example, we have rarely seen Guided Discovery used in practice. Also 263 observed infrequently are the Learner-Initiated style and the Inclusion style (although in 264 programs/schools for special needs children the concepts and ideas of the Inclusion style are 265 predominant). A discussion about why these styles are seldom used, and if this reality is a 266 detriment to effective learning, will be postponed until another time. It is likely more a function 267 of educational philosophy and curriculum than of teacher choice. 268 Episodic teaching. 269 We have used the term ‘episode’ on several occasions thus far in this paper. For us this 270 has become an important and useful concept. In planning a lesson a teacher usually thinks in 271 terms of a class period. A class period is a unit of time, usually designated by the school, 272 agency, or program, during which instruction occurs. So, for example, a school might divide 273 their day into 50-minute segments or a company might offer a course for their employees 274 meeting once a week from noon until 1 p.m. Both teachers and students would typically refer to 275 that hour as a class period. In preparing for a class period the teacher would plan for certain 276 things to happen. The teacher might decide, given this hour of time, s/he might be able to 277 accomplish three things. Each of these three things might have different objectives, different 278 learning experiences, and different anticipated outcomes. In our terms, we would describe this 279 class period as having three episodes. In Spectrum terms an episode is a unit of time within Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 13 280 which the teacher and learner are working on the same objective or set of objectives and engaged 281 in the same teaching style. An episode might last a few minutes, an entire period, or more. 282 So, a lesson or class period will typically include one, two, or more episodes. Each 283 episode has its own learning intent and corresponding pre-impact, impact, and post-impact 284 decisions. This combination of episodes would appear seamless to the learners during the flow 285 of the lesson. Some of the pre-impact decisions for one episode might be occurring during the 286 impact of another episode. Or, and now we are getting fancy, there may be two or more episodes 287 happening concurrently. Also, an episode might extend beyond a typical period and could be 288 continued during the next period. This is not as confusing as it may seem and we’ve found using 289 the episode as the “unit of measure” to be very useful. Spectrum teachers and learners can 290 change episodes easily. Spectrum scholars focus at the episode level in trying to establish 291 linkages between teaching behavior and learning outcome. 292 Clusters. 293 While developing the Sprectrum, Mosston came to realize a break was apparent along 294 separating the landmark styles into two clusters. Again, this is not a “versus” issue and clusters 295 were not included to be divisive. Just as landmark styles identify where teaching behavior lies 296 along the Spectrum (not good or bad), clusters also help to identify the cognitive demarcation f a 297 teaching style. This break occurs between the Inclusion style and the Guided Discovery style 298 and involves the decision about how the learner acquires the content (see Figure 4). If the 299 content is ‘provided’ to the learner and the learner is being asked to reproduce content as closely 300 as possible to the presentation, several teaching styles on the left side of the Spectrum could be 301 proficient for this purpose. The evaluation would compare outcome produced by the learner Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 14 302 against content criteria presented by the teacher. However, if the learner isn’t provide with the 303 content directly but is involved in acquiring or discovering the content him or herself, this would 304 provide a significantly different learning experience, one involving a teaching style within the 305 production cluster. 306 307 Place Figure 4 About Here 308 309 For example, a teacher might be working with a group of students on the concept of 310 balance. The teacher could state simply- “You have balance when your center of gravity falls 311 within your base of support.” And then the teacher might lead them through some examples of 312 this concept- so they could ‘feel it’ in their own movement. Alternatively, the teacher might 313 develop an episode in which, after defining ‘base of support’ and ‘center of gravity,’ the students 314 perform a series of static balance activities, some of which produce stability and others which 315 produce instability. Then the teacher might ask them to write down in their notebooks their 316 answer to the following question- “From your experiences, what is the relationship between your 317 base of support and your center of gravity?” Most of them would come to understand that as 318 long as their center of gravity stayed within their base of support they could maintain stability. 319 But they would come to this understanding experientially, not as a result of the teacher telling 320 them directly. In general this type of teaching has been referred to as indirect (Flanders, 1970) or 321 heuristic. 322 Why would a teacher decide to use what clearly is a much more complicated teaching 323 approach when a more direct approach is available? We will save that question for another time. 324 For the present discussion, in just trying to describe the Spectrum, this bifurcation has been 325 identified. “The cluster of styles A-E represents teaching options that foster reproduction of past Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 15 326 knowledge; the cluster of styles F-K represents options that invite production of new knowledge- 327 that is, knowledge that is new to the learner, new to the teacher and, at times, new to society. 328 The line of demarcation between these two clusters is called the discovery threshold” (Mosston 329 & Ashworth, 2002, p. 11). 330 O-T-L-O Relationship. 331 In describing an episode we said that each episode, in Spectrum terms, has its own 332 objectives, teaching and learning behavior, and outcomes; in other words, its own O-T-L-O. 333 What is the relationship among these components of the teaching-learning process? We believe 334 it is logical, causative, and organic. Mosston referred to these components taken together as the 335 “pedagogical unit” (p. 15). The proposition undergirding the Spectrum is that a particular 336 teaching style will produce predictable learning conditions that, in turn, will produce expected 337 learning outcomes. Will there be times when a particular episode doesn’t work in the sense of 338 producing expected outcomes? Of course, as is true in most human endeavors. But, there are 339 reasons why it didn’t work and those, in most cases, can be determined and, with persistence, 340 rectified. 341 The key component in the O-T-L-O is the teacher’s behavior. Teaching is a purposive 342 activity. But, regardless of the instructional purpose, it is the teacher’s behavior the learner 343 experiences and to which the learner responds. The Spectrum helps to bridge the gap between 344 teacher intent and behavior. It has been argued that using these behaviorally predetermined 345 teaching styles is depersonalizing and mechanistic (Sicilia-Camacho & Brown, 2008). In our 346 experience, just the opposite is the case. Because a Spectrum prepared teacher has an expanded 347 repertoire of alternative teaching styles, s/he can select the style that best matches intent to reach 348 a given objective. Spectrum Revisited manuscript 349 Page 16 The O-T-L-O identifies the critical elements of the teaching-learning process at the 350 episode level. For any given episode, the O-T-L-O should be seamless. Teacher intent and 351 behavior should be congruent, learning activities should clearly support intent, and outcomes 352 should match objectives. If there is incongruity or discord among these elements, outcomes will 353 not match objectives. It is also important to appreciate that any teaching episode exists within a 354 larger context. Most episodes are segments of a whole. 355 Another dimension of the O-T-L-O incorporates the perspective of breadth or degree of 356 specificity, from a narrow to a broad perspective. Perhaps a simple way to look at this 357 dimension is in terms of three levels of perspective. The ‘micro’ level is about a particular 358 episode/lesson, the ‘meso’ level focuses more at the unit or the year-long perspective, and the 359 ‘macro’ level offers the broadest perspective. Each element of the O-T-L-O can be examined at 360 each level. For the most part teachers live at the micro level. Nevertheless, we must all be aware 361 of this broader context and be cognizant of any incongruities between intent and action (see 362 Figure 5). 363 364 Place Figure 5 About Here 365 366 367 368 Response to a Critique of the Spectrum In this paper we’ve attempted to provide a retrospective of the Spectrum’s development 369 and to discuss five refinements incorporated since the first Spectrum book was published in 370 1966. In closing we turn our attention to an article about the Spectrum by two European 371 colleagues. In 2008 Alvaro Sicilia-Camacho and David Brown had an article published in 372 Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy in which they submitted some of the concepts Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 17 373 undergirding the Spectrum to philosophical analyses. It was their article, in fact, that motivated 374 us to write this article in response. Actually, the present article is not a direct response to Sicilia- 375 Camacho and Brown because we are not prepared to engage them in a philosophic discussion 376 (we are teacher educators, not philosophers). However, we found some of their understanding to 377 be interesting and thought a retrospective about the Spectrum, referencing some of the issues 378 they raised, would be of interest to the physical education scholarly community. 379 Sicilia-Camacho and Brown wrote, “The original Spectrum of teaching styles was made 380 up from a collection of eight commonly observed teaching approaches or styles….” (p. 87). 381 While the eight original teaching styles identified by Mosston were used in practice before his 382 1966 book was published, that was not how the Spectrum was developed. He didn’t ‘collect’ 383 known teaching approaches or methods and organize these approaches into a framework. As the 384 Spectrum evolved from a premise, to the Anatomy, and then to the landmark styles, it is 385 important, we believe, to understand the nature of Mosston’s Spectrum of Teaching Styles. 386 Sicilia-Camacho and Brown (2008) contend that there was a paradigm shift from a 387 “versus (opposing) notion of learning and teaching to a non-versus (non-opposing) notion” (p. 388 85) of learning and teaching beginning with the second edition of Mosston’s text (1981). They 389 wrote, “While seemingly innocuous, we contend that this shift can be seen in epistemological 390 terms as an advance (back) towards a positivism in PE despite years of dialogue from emerging 391 interpretive standpoints” (p. 85). In our opinion, they read more into Mosston’s ‘paradigm shift’ 392 than he intended. As we tried to explain above, the shift had more to do with a misrepresentation 393 within his original schema than with the Spectrum itself. In his first schema, Mosston included 394 the diverging lines (see Figure 2) that did imply direction, ‘from Command to Discovery.’ Even 395 though that statement at the time represented his philosophy about education, his Spectrum work Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 18 396 was committed to the standard of universality. Upon reflection he came to understand this 397 misrepresentation and changed the lines to parallel. 398 Before the Spectrum was conceived, when pedagogical ideas like didactic and heuristic 399 teaching, direct and indirect teaching, problem-solving, cooperation learning, mastery learning, 400 individualized instruction, etc., were being discussed, they were often presented in an 401 oppositional relationship. For example, one expert would claim that indirect teaching was better 402 than direct teaching and another that individualized instruction was better than group instruction. 403 One of Mosston’s motivations in devising the Spectrum was to show the positive connections 404 among all these ideas. Once the idea of the Spectrum was clear, styles could be discussed in 405 terms of both their commonalities and their differences. Mosston never viewed individual 406 teaching styles as “oppositional” to each other as Sicilia-Camacho and Brown (2008, p.88) write. 407 Rather, he viewed the styles as complimentary to each other. Mosston observed the utility of 408 each style in terms of the different relationships it could forge between teacher, learner, and 409 content. 410 The authors also discussed the use of clusters, categories of Reproduction and 411 Production teaching styles. It should be noted that in the first edition of Teaching Physical 412 Education (1966), these categories had not yet been introduced. They didn’t appear until the 413 third edition. But more importantly, the identification of clusters was not introduced to produce 414 contention or opposition; command ‘versus’ discovery. The clusters provide more of a 415 navigational reference point along the Spectrum. 416 Sicilia-Camacho and Brown (2008) expressed their concern about teachers losing their 417 individuality and creativity when using the Spectrum. They contend, “any pedagogical model 418 that attempts to universalize and objectify will necessarily have to separate personhood from Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 19 419 pedagogy, and thereby once again devalue and neglect the important issue of subjectivity” (p. 420 87). They viewed the Spectrum as something that makes teaching more de-personalized and 421 more technocratized (if there is such a word). The authors describe the styles as “neutral, 422 technical instructional devices that reflect no particular value” (p. 98). 423 We have found just the opposite to be true. The Spectrum, rather than depersonalizing 424 the teacher, can serve to provide more congruency and fidelity between a teacher’s intent and 425 her/his in-class behavior. Mosston’s push toward identifying “universal” structures in pedagogy 426 was not motivated in the least by a desire to diminish the creativity or individualization of 427 teachers. The Spectrum provides teachers with a versatile tool through which they can express 428 their creativity and individuality. Just as painters use color and brush technique to create highly 429 personalized visions, so teachers use teaching styles to help achieve their instructional intent in 430 the most effective, efficient, and exciting way possible. 431 The authors describe the Spectrum as being devoid of value. On the contrary, each style 432 does express a value or values. But these are mainstream values supported by most societies. 433 For example, the Command style expresses the value of conformity, the Reciprocal style the 434 value of cooperation, and the Guided Discovery style the value of thinking logically. So, for 435 example, when the Reciprocal style is used in an archery episode to provide immediate feedback 436 to learners about their archery form, the learners, who are giving and receiving feedback while 437 performing, are experiencing the value of reciprocation but they are not being indoctrinated in 438 some sort of socialistic philosophy. When you go past the individual styles and consider the 439 Spectrum as a whole at the macro level, the Spectrum expresses both many values and none in 440 particular. It is up to the teacher to craft the scenario. It is like saying that learning to play a 441 piano is a ‘technocratic’ endeavor. Teaching the brain to trigger certain nerves to respond when Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 20 442 particular notes are observed is, we suppose, technocratic, but that’s not the end in learning 443 piano- it is the means for gaining a manner for self-expression. 444 In our experience most teachers can learn to behave comfortably and genuinely in most, 445 if not all, of the teaching styles. We have not observed teacher personality or philosophy having 446 a deleterious effect on acquiring the full range of teaching styles. We have seen the most liberal 447 teachers effectively use the Command style and the most conservative teachers use the Divergent 448 Discovery style. Utilizing alternative teaching styles is not a matter of personality or philosophy. 449 It is a matter providing the most appropriate learning conditions for the objective at hand. 450 Sicilia-Camacho and Brown (2008) don’t seem to accept this and argue that “this is only 451 achievable if that teacher ignores aspects of the underlying educational theory that informs these 452 styles, replaces them with a form of pedagogical pragmatism, and ‘performs’ them with the 453 authenticity of an accomplished actor” (p. 97). 454 We have advocated “mobility ability” as a goal for professional educators. Mobility 455 ability is the teacher’s ability to change teaching styles to meet changing objectives and/or 456 conditions. Interestingly, we have a couple of colleagues (now retired) who studied and 457 implemented Spectrum for over 30 years and both only used three styles. These were terrific and 458 successful teachers, well-respected for their abilities. How can this be true? As we noted above, 459 this has to do more with the curriculum they were following than their philosophy. In both cases 460 the major goal of their programs was limited to performing a specific set of sport skills. To do 461 this they used mainly the Practice style, with some episodes in Command and Reciprocal used on 462 occasion. In our experience, and it is also our belief, teaching styles are not necessarily 463 employed evenly across the typical physical education curriculum. The Spectrum was developed 464 to provide a comprehensive view of teaching behavior and was not meant to be a prescriptive Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 21 465 tool regarding curriculum development. You can have an excellent curriculum and only use a 466 limited number of teaching styles. You can also be an excellent teacher and only use a limited 467 number of teaching styles. 468 Teaching Spectrum theory to pre- and in-service teachers both in North America and 469 abroad for many years, we have seen many teachers struggle in the beginning, as we did, 470 attempting to learn new behaviors, reducing inappropriate behaviors, and reconciling differences 471 between intent and action. Using the painting analogy, it is like mastering new stroke 472 techniques, we suppose. But once these behaviors become internalized and part of one’s 473 repertoire they recede from consciousness and during implementation the focus shifts from 474 oneself to the larger context. 475 Sicilia-Camacho and Brown (2008) apparently do not appreciate the concept of episodic 476 teaching. They wrote: “For example, on Monday a teacher might implement a teaching style 477 geared towards behaviourist understandings, while on Tuesday, the teacher might change this 478 approach in order to develop a more personal and autonomous constructivist teaching style and 479 so on” (p. 100). In our experience, Spectrum teachers never use the same teaching style all day. 480 Differing objectives trigger the use of different styles. The authors go on to discuss situations in 481 which two or more teaching styles are employed on the same day or even within the same period 482 and they express concern that these approaches are contradictory. We have conducted and 483 observed many lessons where episodes, utilizing disparate teaching styles, were used seamlessly 484 and effectively during the same period and were even used concurrently. For example, when 485 teaching a new motor skill to a class of second graders, the teacher may introduce the critical 486 skill elements of the movement in a short Command style episode, next have the children 487 practice the motor skill at their own pace in a Practice style episode, follow skill practice with a Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 22 488 Reciprocal style episode where the children practice the motor skill while simultaneously 489 engaged in giving and receiving feedback (social development) and analyzing a partner’s motor 490 skill performance (cognitive development), and finally end the 30 minute lesson with a 491 Command style episode where the children review the critical skill elements that were 492 introduced during the first episode of the lesson. In this example, three different teaching styles 493 are used in a carefully selected sequence to help the children accomplish a series of similar and 494 different learning outcomes. 495 Early in their article Sicilia-Camacho and Brown (2008) suggest that Mosston used the 496 Spectrum to promote his “progressive liberal education” agenda (p. 90). But that was the 497 concern Mosston addressed when he changed the schema in the second edition of Teaching 498 Physical Education (1981). That Mosston believed in progressive, liberal, education is not in 499 question- he did! But, he envisioned the Spectrum going beyond his own experience and his 500 own philosophy- to offer a more universal perspective. After the first edition was published, he 501 came to realize that his philosophy was reflected in the first schema, developing learners as 502 independent decision-makers. Again, that’s why he revised his original schema to provide what 503 he referred to as the ‘non-versus’ perspective. 504 Sicilia-Camacho and Brown (2008) state, “The non-versus notion of teaching styles bases 505 itself on knowledge predominantly generated through quantitative research over the last few 506 decades” (p. 97). We have no idea how they came up with that idea. Mosston was not a 507 researcher in the classical mode. He was a scholar and read voraciously, but none of the 508 Spectrum’s structure or logic was based on quantitative research. Some of Mosston’s students, 509 his followers, led the push into quantitative research. Spectrum Revisited manuscript 510 Page 23 Sicilia-Camacho and Brown (2008) state that although “tempting,” it is very difficult to 511 scientifically “to establish predictive and causal relationships between human behaviour” (p. 97). 512 We agree with this view, but as young scholars we were trying to engage in the 1973 challenge 513 laid down by Nixon and Locke to provide empirical evidence about the Spectrum’s 514 effectiveness. In our view the relationship between teaching and learning is positive. We 515 believe what a teacher does in the classroom can make a difference. Of course, both the teacher 516 and learner must be willing participants in this endeavor. The teacher’s behavior helps to craft a 517 learning environment that supports the learning objective at hand. And, we state again, “results 518 to date confirm the theory’s power to both describe teaching events and predict teaching 519 outcomes” (Goldberger, 1992, p. 45). We understand that there are many factors difficult to 520 control that affect learning; including learner factors (such as learner aptitude and learner 521 motivation), teacher factors (such as teacher content knowledge, commitment, and enthusiasm), 522 and many other contextual factors. Nevertheless, we do still believe that the teacher’s behavior, 523 and the use of alternative teaching styles, can make an important difference in terms of learning 524 outcomes. 525 Sicilia-Camacho and Brown (2008) appear to bristle at the suggestion that teaching and 526 learning have a positive relationship. “In this sense, the non-versus logic embedded in the 527 revised version of the Spectrum of teaching styles is a clear attempt at objectification and 528 universalism, that derives directly from its positivistic epistemology” (p. 98). This paradigm 529 shift concerns how Mosston’s teaching styles Spectrum has come to be conceptualized in an 530 increasingly universalizing and technocratic direction as exemplified by Goldberger’s (1992) 531 proclamation that “although the theory has not yet completed the full program of testing Nixon 532 and Locke called for, results to date confirm the theory’s power to both describe teaching events Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 24 533 and predict teaching outcomes” (p. 45). According to Sicilia-Camacho and Brown, one of the 534 reasons why the Spectrum has not been submitted to a thorough philosophic review and 535 evaluation is because the focus of the educational leadership and research community has been 536 on issues dealing with PE content and curriculum. We agree. 537 In conclusion, we would enjoy engaging our colleagues, Sicilia-Camacho and Brown, in 538 further discussion about the Spectrum, whether face-to-face, virtually, or via scholarly 539 exchanges. However, we don’t think they like us support the Spectrum very much. In their 540 paper they called us some pretty nasty things (we think). Since most of it was ‘philosophy-talk’ 541 we’re really not sure what they meant. They referred to us as positivistic, de-personalized, re- 542 objectified, neo-liberal technocrats. But in truth, as best as we can determine… Yup, that’s us! 543 Guilty as charged. 544 545 Spectrum Revisited manuscript 546 Page 25 References 547 Flanders, N. (1970). Analyzing teaching behavior. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publish Co. 548 Goldberger, M. (1992). The Spectrum of teaching styles: A perspective for research on teaching 549 physical education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance, 63(1), 42-46. 550 551 Mohnson, B. (Ed.). (2003). Concepts and principles of physical education: What every student needs to know. Reston, VA: AAHPERD. 552 Mosston, M. (1966). Teaching physical education. Columbus, OH: Merrill. 553 Mosston, M. (1981). Teaching physical education (2nd ed.). Columbus, OH: Merrill. 554 Mosston, M., & Ashworth, S. (1986). Teaching physical education (3rd ed.). Columbus, OH: 555 556 557 558 559 Merrill. Mosston, M., & Ashworth, S. (1994). Teaching physical education (4th ed.). New York: Macmillan. Mosston, M., & Ashworth, S. (2002). Teaching physical education (5th ed.). San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. 560 Nixon, J., & Locke, L. (1973). Research on teaching physical education. In R. Travers (Ed.), 561 Handbook of research on teaching (2nd ed.), pp. 1210-1242. Chicago: Rand McNally. 562 Sicilia-Camacho, A., & Brown, D. (2008). Revisiting the paradigm shift from the versus to the 563 non-versus notion of Mosston’s Spectrum of teaching styles in physical education pedagogy: 564 A critical pedagogical perspective. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 13(1), 85-108. Spectrum Revisited manuscript 565 Page 26 Figure 1. The Anatomy of Any Style 566 567 568 Pre-impact (-) 569 Impact (-) 570 Post-Impact (-) 571 572 573 574 575 Figure 2. Spectrum Schema 1966 576 _________________________________________________________________ 577 578 A B C D E F etc 579 580 Minimum learner decisions 581 ____________________________________________________________________________ 582 583 Maximum learner decisions Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 27 584 585 Figure 3. Spectrum Schema 1981 586 587 588 589 A B C D E F G H I J 590 591 592 Minimum learner decisions Maximum learner decisions 593 594 595 596 Figure 4. The Spectrum Clusters 597 598 599 600 A B C D E F G H I J 601 602 603 604 605 606 Minimum learner decisions Maximum learner decisions Spectrum Revisited manuscript Page 28 607 608 Figure 5. O-T-L-O Three Level Schema (revised August 2008) 609 610 611 612 613 MACRO LEVEL 614 615 616 617 618 619 620 621 622 Objective MESO LEVEL Teaching Outcome MICRO LEVEL Learning