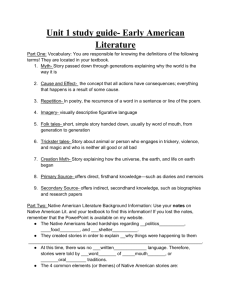

Chapter One: Alternate Originals: Canonizing

advertisement