Medial - University of Ilorin

ASPECTS OF YIWOM

MORPHOLOGY

A LONG ESSAY SUBMITTED TO THE

DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS AND NIGERIAN

LANGUAGES, FACULTY OF ARTS, UNIVERSITY

OF ILORIN, ILORIN, NIGERIA.

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE

REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF BACHELOR OF

ARTS DEGREE (B.A. HONS.) IN LINGUISTICS

SALAUDEEN AMUDALAT TOYIN

MATRIC NO: 07/15CB094

JUNE 2011

CERTIFICATION

This research work has been read and approved as meeting the requirement for the award of B.A. (Hons) degree in the department of linguistics and Nigerian languages,

University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria.

________________________ ____________________

Mrs. S.O.O. Abubakre Date

Supervisor

_______________________ ______________________

Prof. A.S Abdulsalam Date

Head of department

_______________________ ______________________

External examiner Date

DEDICATION

This project work is dedicated to Almighty Allah and to my loving parents, Mr. and Mrs. Salaudeen.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All profound gratitude goes to my creator for His mercies and guidance. I will forever be grateful to Allah who gives knowledge and wisdom to whomever He likes.

It is very important to express my sincere appreciation to my loving parents because without them, there is no me today.

I am saying a very big thank you for your prayers, support, advice and most importantly your financial support. You are one in a million, kudos to you. May you live long to reap the fruits of your labour

My gratitude goes to my supervisor, Mrs. S.O.O.

Abubakre for her motherly advice, helpful remarks and

guidance throughout the period of my research work. May God reward you abundantly ma.

Also beholding my acknowledgment are my lecturers both in my department and other departments, I say thank you to all of them for the knowledge acquired from them, and may Almighty Allah reward you all.

My uncountable appreciation goes to my informant, Mr.

K.G Tislet and his wife for their help and hospitality during the time I was collecting the data, may God reward you for making this work a successful project.

I own a great deal to my family the Salaudeens, Mr. Dele

Awotunde, Mr. and Mrs. Agboola, Pastor Lekan Awotunde,

Mrs. Alarape, Mr. Lanre Awotunde,Mr. Lanre, Mr. James,

Daddy and Mummy Bakare and family, Mr. and Mrs. Adeoye and family, Mr. and Mrs. Obayomi, Mr. and Mrs. Olatunde and family, Mr. and Mrs. Afolaranmi and family, Mr. and Mrs.

Ayandibu, Mr. and Mrs. Bilewu, Mr. and Mrs. Taiwo, Prof. and

Mrs. Oyejola, Prince and Mrs. Yusuf and family, mummy

Asonibare, Mrs. T.Z Salaudeen, Mrs. Mulikat Yakub, Mr. Femi

Afolayan, my lovely younger ones Azeezat, Ismail and Halimat

Salaudeen. My younger ones, you are too numerous to be mentioned, I appreciate you all. The entire Afolayan family, and many others who have been of great help towards the completion of my programme in school.

Also I appreciate Mrs. Kolade for being there for me during the writing of the project, I say thank you a lot ma may the good Lord reward you.

Finally, I appreciate my friends, Tope, shakira, sunday ,

John, Stephen, Kemi ,Deborah, Ife (Aunty Mulika), Aunty

Tosin, Kafayat Apeke ,I.d , Akeem, Mistura, Aunty Yetunde,

Lekan, Abdulhaq, Tunji, Tosin, Bisi, all Abbabo abode students and my course mates you are the best see you all at the top.

LIST OF SYMBOLS AND DIAGRAMS

[΄] High sound

[`] low sound

[ ] mid sound

Syllable

Figure 1: The Genetic classification of Yiwom

Figure 2: The consonant chart of Yiwom

Figure 3: The vowel chart of Yiwom

Figure 4: The pronoun table of Yiwom

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TITLE

TITLE PAGE

PAGE

CERTIFICATION ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; ii

DEDICATION ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; iv

LIST OF SYMBOLS AND DIAGRAMS;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; viii

CHAPTER ONE: YIWOM LANGUAGE AND ITS SPEAKERS

1.0 General Introduction ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 1

1.1 General Background ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 1

1.2 Historical background ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 2

1.3 Geographical Location ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 4

1.4 Sociocultural Profile ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 4

1.4.1 Religion ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 5

1.4.2 Ceremonies ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 5

1.4.2.1Naming ceremony ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 5

1.4.2.2Marriage Ceremony ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 6

1.4.2.3Burial Ceremony ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 8

1.4.3 Festivals ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 8

1.4.3.1Circumcision ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 8

1.4.3.2Initiation ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;;; ;;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 9

1.4.4 Dressing ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; ;;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 10

1.4.5 Traditional Administration ;; ;; ;; ;; ; ;; ;;; ;; ;; 11

1.4.6 Economic ;;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; ; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 12

1.5 Genetic classification ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;;;; ;;; ;; 13

1.6 Scope and Organization ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 15

1.7 Theoretical Framework ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 16

1.8 Data Collection ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 17

1.9 Brief Review of Theoretical Framework;; ;; ;; ;; 19

CHAPTER TWO: SOUND INVENTORIES AND SOUND

PATTERNS IN YIWOM

2.0 Introduction ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 25

2.1 Sound Inventories in Yiwom ;; ;;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 26

2.2 Tonal Inventories ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 46

2.3 Syllable Inventories ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 51

2.4 Brief Review of Phonological concept in Yiwom ; 56

CHAPTER THREE: MORPHOLGY OF YIWOM

3.0 Introduction ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 59

3.1 Morphology and Morphemes in Yiwom ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 59

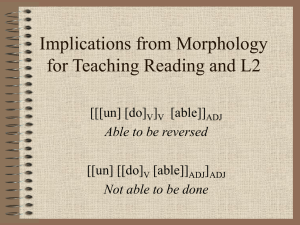

3.2 Types of Morphemes ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; ;; ;; ;; 67

3.2.1 Free Morphemes ;; ;; ;; ;; ; ;; ;;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 67

3.2.2 Bound Morphemes ;; ;; ;; ; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 70

3.3 Functions of Morphemes ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; ;; ;; ;; 72

3.3.1 Inflectional Morphemes ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 72

3.3.2 Derivational Morphemes ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 74

3.4 Noun ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 76

3.4.1 Proper Noun ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;;; ;; ;; ;;; ;; ;; ;; ;;77

3.4.2 Common Noun ;; ;; ;; ;;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 78

3.4.3 Countable Noun ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; ;; ;; ;; ; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 79

3.4.4 Uncountable Noun ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 80

3.4.5 Concrete Noun ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; ;; ;;; 80

3.4.6 Abstract Noun ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 81

3.5 Verb ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 82

3.5.1 Transitive Verb ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 83

3.5.2 Intransitive Verb ;; ;; ;; ;;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; ;;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 84

3.6 Adjective ;; ;; ;; ; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 84

3.7 Pronoun ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 86

3.7.1 Personal Pronoun ;; ;; ;; ;; ;;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;;; ;; ;; ;; 87

3.7.2 Reflexive Pronoun ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 87

3.7.3 Possessive Pronoun ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 88

3.7.4 Interrogative Pronoun ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 88

3.8 Adverbs ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 88

3.9 Determiners ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 90

3.10 Number ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 92

3.11 Preposition ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 93

3.12 Conjunction ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 94

3.13 Language Typology ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 95

CHAPTER FOUR: MORPHOLOGICAL PROCESSES IN

YIWOM

4.0 Introduction ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 101

4.1 Morphological Processes ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 101

4.1.1 Compounding ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 103

4.1.2 Borrowing ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 106

4.1.3 Affixation ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 108

4.1.4 Reduplication ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 111

4.1.5 Refashioning ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 114

CHAPTER FIVE: SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND

RECOMMENDATION

5.0 Introduction ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 115

5.1 Summary ;; ;; ;;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 115

5.2 Conclusion ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ; 117

5.3 Recommendation ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;;117

REFERENCES ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 119

APPENDIX ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; ;; 124

CHAPTER ONE

YIWOM LANGUAGE AND ITS SPEAKERS

1.0 GENERAL INTRODUCTION

This chapter Introduces the language and its speakers, other issues in the chapter includes the historical background, sociocultural profile, geographical location, genetic classification, scope and organization, theoretical framework, data collection, data analysis, brief review of the chose theoretical framework and the literature review.

1.1 GENERAL BACKGROUND

Crystal (2008:283) defines linguistics as “the scientific study of language” .This means that linguistics is the scientific study of natural language as everything concerning language is undertaken in linguistics. This project work is on the aspect of morphology of Yiwom language.

The speakers of the Yiwom language are estimated to be

14,100 in the year 2000. The Yiwom people are also known as

Garkawa, Gerkanchi, Gerka and Gurka. The speakers call themselves Yioum instead of Yiwom and they will be referred to as Yiwom in this project.

1.2 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

Hiel-Yioum is what they call their town, but the Fulani people call them Garkawa. It is a unit in the southeast corner of the present Mikang local government of Plateau states in

Nigeria. The unit consists of an undulating county slightly rising from south to the Garkawa hills in the extreme North.

The Yiwom people have been in their present home for

upwards of two hundred years (200 years). The Pitop came to the area first and provided itself a stockaded town at a place called Hakbap. The Rohta followed second and settled in Kiel-

Hiel at Rohta-Hills, north of Hiel-Yioum. Other families arrived in large detachments one after the other, and took refuge at

Kiel-Hiel. Rohta rock was fortified and was capable of withstanding siege.

About the middle of nineteenth century, the families came from their hills to live in their present homes. Yiwom was once divided into two distinct sections which are the Hill and

Plain, the former which is the Hill at Rohta, the latter which is the plain at Pitop. According to legends preserved by both sections, their ancestors sprang from the grounds. The Rohta maintain that they are from river gulnam in the hills, while the

Pitop says that their ancestors emerged from the earth. The word “Yioum” in Yiwom dialect means leave. The analogy being: as trees grow out of the ground, so their ancestors came into being. The name “Garkawa” was given to them by

Fulani/Hausa traders owing to their military prowess and stubbornness. The name derived from “gagararru”, which in the occurrence of the time became “Garka and Ba Garko and finally, Garkawa”. History shows the Yiwom people to have been a formidable tribe. Legend points to the fact that all the families mentioned and who call themselves Yiwom are of

Jukun stock that migrated after the breakup of Kwararrafa

Empire (West of Bukundi) and wandered about until they found their present home. Until now, they kept very much to themselves and are good agriculturalist. Yiwom is regarded by the British as one of the “unconquered tribes” living near or along the trade routes. Source Dabup (2009:67-73)

1.3 GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION

The home of the Yiwom speakers is situated in the southeast of Mikang local government in Plateau state,

Nigeria. It is found in coordinates 9 0 00 north, 9 0 35 East and

9 0 North, 9.583

0 easts. It covers an area of approximately

739km 2 which is 285.3 square meters, its time zone is WAT

(UTC + 1). It is bounded in the North and East by the Lantang section of Yergam, southeast by the way to Dampar, south by

Inshar and West by the Lalin section of Montol.

1.4 SOCIOCULTURAL PROFILE

Yiwom is a Chadic language of the Afro-Asiatic language family spoken by the Garkawa people of Plateau state, Nigeria.

They have several clans such as Rohta, Killah, Balbro, Pitop

Talim, Lahl, Pensong, Gwar-Gimjim, Bal’Nlah, Longkrom and

Wai. Each clan has its own priest called Bangkrom-Krom and its own traditional religion.

1.4.1 Religion

The Yiwom speakers practice all kind of religion including

Christianity, Islam and animism. In the olden days, the speakers of the language were mainly practicing animism but over the years, Christianity has taken over and a few practice

Islam.

1.4.2 Ceremonies

A lot of ceremonies go on in the Yiwom culture which includes marriage, burial ceremony.

1.4.2.1 Naming Ceremony

Yiwom speakers do not celebrate naming ceremony. It is the father side that names a child and it is done immediately or at most after three of five days after the child had been given birth to. There is no celebration a lady is not given the chance to name a child even though a mother can name a child, it has to be with the consent of the father but it is usually the father side that gives the child a name.

1.4.2.2 Marriage Ceremony

When a man seeks a wife in the Yiwom customs, he makes his proposals to the girl directly, when the girl is comparatively young. If she accepts him as suitor, he then sends two or three of his friends to her and asks her if she had accepted their friend, as her suitor. If she says yes, the girl in turn informs her mother that she has accepted the man. Her parents will also call her and question her closely as to

whether she has really accepted the suitor. Until the parents are satisfied and certain, they will not receive any presents from the suitor. Once they accept presents from the suitor, the girl is considered betrothed and no one else makes advances to her. The gifts begin at an early stage, at a later stage, the boy builds a mud hut and enclosure for the girl’s mother and he also farms every year for the girl’s father. There would not be any sexual relationship with his fiancée until after marriage in Yiwom’s custom, there are three modes of contracting a marriage and these are:

(a) Marriage by system of exchange:

In this case, the wife and her offspring virtually become the property of her husband, but with the passage of time this has died out.

(b) The second mode of marriage is by payment of small customary bride-price. Under the small bride-price system, it was easy for a woman to change her husband, but that hardly happened.

(c) Cousin Marriage:

This is considered the best form of marriage on the ground that they keep wealth within the family. The second and most important reason is that divorce is not permissible and, therefore, was permanent.

1.4.2.3 Burial Ceremony

Mourning and burial rites were done in yester-years by making cylindrical shaft with niche, in which the body was wrapped in a cloth. Nowadays, burial is in a rectangular grave with a niche, reclining on a mat facing east, if a man or west, if a woman. This type of grave is of recent adoption, being easier to make than the cylindrical shaft with niche.

1.4.3 Festivals

Festivals in the Yiwom custom include circumcision, initiation, hunting etc.

1.4.3.1 Circumcision

Circumcision rites among male children are carried out every year. Circumcision was regarded as a rebirth, the actual operation of circumcision was performed in order of seniority, and it was not possible for a younger brother to be circumcised at the same time as an elder brother. This is done in the spring, dry season of the initiation year. Circumcision is a necessary antecedent to marriage, as among some other tribes. A boy’s initiation is often held-up by the rule that two brothers by the same mother may not be simultaneously. The younger, even though he has passed the age of puberty, must wait for the succeeding batch. All persons initiated together are regarded as being on the same social footing, and it would improper that a younger brother should be given social equality with an elder. The custom and tradition of Yiwom disallowed female circumcision.

1.4.3.2 Initiation

After healing and a year of the circumcision, if the boy reached the age of puberty, the head of the family took him to an isolated enclosure for initiation. The account and method of initiation are unknown to those who have not been initiated.

After the initiation, the boy was considered to be a responsible member of the community and was no longer required to conceal himself with the women and children. They are warned to show respect their seniors and if they fail to in any of their duties towards your elders, they will be prostrated with sickness.

Hunting festivals takes place after the harvest, in bush, bordering the River Wase to the East. Most types of animals like elephants were found there. Weapons such as spears, hunting-knives, bows and poisoned arrows were some of the weapons used. The spears and arrow heads were dipped in poison before use in the hunt.

Masquerades is kept by each clan and appears from time to time, armed with a whip and chastising recalcitrant boys or

any woman who has the effrontery to remain within his reach.

Masquerades are kept secret from the women and boys who have not been initiated.

1.4.4 Dressing

In the olden days, the young girls wear “pàtàrí” and it is like a short skirt and the married women wears something like the ìró and bùbá which the Yoruba women wears, the men wears ‘bìndé’ like the Ibos, a short knickers called ‘gúd’ and a long trouser called ‘mùrdú’ or ‘wòrdó’. The modern dressing is like the normal dressing which is the modernized way of dressing and they mostly sew ìró and bùbá and not skirts.

1.4.5 Traditional Administration

The overall head of the Yiwom is called ‘Migher Yiwom’ which means “Head of Yiwom”. The chiefs are recognized by putting on a red cap and holding a staff. The selection of the chiefs is done in a democratic way and through the clan rotation; each clan presents two or three people who are then elected into position. There is also the leader of each clan

which is called ‘Migher Pitop’ or any name of the clan which can be ‘Migher Rohta’ which means ‘head of the Pitop’; this is like a subordinate to the ‘Migher Yiwom’ who has the power to choose who he wants as his head of the clan. If a clan is chosen as the ‘Migher Yíwóm’ this year, it will be another clan next time. The war chief is called ‘Migher Klàng’ which means

‘head or leader of war’ and a local chief is called ‘Bangkrum krom’.

1.4.6 Economic

The Yiwom speakers are good farmers. All the usual crops and cereals are grown by them, with the exception of the onion, cassava was only recently introduced and yams were not grown to any commercial quantity. They did not significantly practice crafts except simple mat making.

Blacksmiths were few in number as iron was imported from the Burumawa tribe and some by the Fulani/Hausa traders from Ibi. The market is held everyday but Tuesday of every week continues to be the market day. Trade-by-barter was

customary among tribes, cowries were never used. Taxes were and still paid in money but not plentiful.

Children are first taught their mother tongue, Yiwom and then Goemai and Jukun languages. A great number are able to speak Hausa as well. They do not have tribal marks, except for personal adornment. “The tribe is immensely proud of itself, in former days the people were feared by all and conquered by none”, writes Mr. Hale Middleton, Resident of

Plateau Province in 1931. Dabup (2009:74-95)

1.5 GENETIC CLASSIFICATION OF YIWOM

Genetic classification is a sub-grouping of all related languages into a genetic node. It is the way we classify all languages that are related into one group, domain or node. It is sometimes called phylo-genetic classification. The relationship between languages is sometimes close as evident with Yiwom and Montol and sometimes more distant as with

Shona and Fulani.

Yiwom language is part of the Chadic family which is in turn part of Afro-Asiatic family. Afro-Asiatic consists of some

353 languages and Chadic is made up of 200 languages.

(Ethnologue website), Yiwom is one of 200 Chadic languages.

The diagram of the Genetic Classification of Yiwom language is drawn below.

Afro – Asiatic language family

Chadic Semitic Cushitic Ancient Egyptian Berber

Mandra Gidder Musgu Bana Sahel Western Kotoko Bata-Tera

Group group Group Group

Daba Matakom Gisila

Group Group Group

Bolewa-Plateau Group Hausa Group Ngizim Group Warjawa-Gesawa group

Bolewa Subgroup Ron Subgroup Plateau Subgroup

Angas Ankwe Bwoi Chip DimukGoramJortoKwollaMiriamMontol Sura Tai YIWOM

Figure 1: The Genetic classification of Yiwom language

Source: Fivaz and Scott 1977

1.6 SCOPE AND ORGANIZATION

This research is on the aspects of morphology of Yiwom language. It introduces the language and its speakers. It is on the morphemes in Yiwom language and the morphological processes, that is how words are formed. For the easy presentation of this research, this project work is divided into five chapters.

The first chapter is the general introduction, history of the language, sociocultural profile, geographical location, genetic classification of the language, scope and organization of the study, theoretical framework, data collection, data analysis, review of chosen theoretical framework and literature review.

The second chapter is on the sound inventories and sound patterns in Yiwom which includes the sound inventory, tone inventory, syllable inventory.

The third chapter discusses the morphology of Yiwom; basic morphemes in the language, and the language typology.

The fourth chapter is on the morphological processes in the language which includes borrowing, compounding, affixation, reduplication and refashioning.

The fifth and last chapter summarizes the work, present the conclusion of the project work, as well as offer suggestions on further research

1.7 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

There are two complementary approaches to morphology;

Analytic and synthetic. The linguist needs both.

The analytic approach has to do with breaking words down, and it is usually associated with American structuralist linguistics of the first half of the twentieth century. These linguists were often dealing with languages that they had never encountered before, and there were no written grammars of these languages to guide them it was therefore crucial that they should have very explicit methods of linguistic analysis. No matter what language, we need analytic methods that will be independent of the structures being examined.

The second approach is more often associated with theory than with methodology. This is the synthetic approach; it basically says “I have a lot of little pieces here. How do I put them together?” This question presupposes that you already know what the pieces are so in a sense; analysis in some way xxix

must precede synthesis. Synthesis really involves theory construction from a morphological point of view, the synthetic question you ask is “How does a speaker of a language produce a grammatically complex word when needed?”. The primary way in which morphologists determine the pieces they are dealing with is by examination of language data. They must pull words apart carefully, taking great care to note where each piece came from to begin with.

1.8 DATA COLLECTION

In collecting the data, the method used was the informant method. According to Samarin (1967), “Field linguistics is primarily a way of obtaining data and studying the linguistics phenomenal therein”. After the collection of the data using the informant method, and the data have been collected using the

Ibadan 400 list, and the frame technique since it is the aspect of morphology of the Yiwom language. The Ibadan word list consist of four hundred basic words in English which will be collected in the language being worked on and the frame technique which includes some sentences in the language which have the English equivalents and then, the wordlist is xxx

recorded using a tape recorder or video recorder so as to have something to refer to when working on the data. Recording the data will help to put tones on the words and transcribe the words. The data is then analyzed and being worked upon.

The information’s of the informant used are:

Name: Kamlong Gabriel Tislet

Age: 42 years

Home Town: Pituop, Garkawa

Other languages spoken: English, Hausa, Goemai, Tehl

Work: Policeman

How long he has lived in home town: 23 years

1.9 BRIEF REVIEW OF THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The analytic and synthetic approaches are good approach to this particular language because it does not require that a linguist have a previous knowledge of the language before he or she is able to apply it. The approaches allow a linguist to deal with a language they have never encountered before. A linguist examines a language data and then pulls words apart carefully to know where each piece came from. xxxi

Aronoff and Fudeman (2005:12) say a linguist needs both the analytic and synthetic approach to morphology and they are complementary approaches to morphology. And this is the main reason why this approach was chosen as the theoretical framework for analyzing the aspect of morphology of the Yiwom language.

The Yiwom language has no written grammars and has never been worked on. It is therefore necessary that the words in the language are broken down before being synthesized. The analytic methods will be independent of the structure, being examined. After knowing the pieces of the language through analytic approach, the synthetic approach asks the question of how to put the pieces together to make complete sense in the language. Part of the analytic approach is the analytic principles which states that:

(i) Forms with the same meaning and the same sound shape in all their occurrences are instances of the same morpheme. xxxii

(ii) Forms with the same meaning but different sound shape may be instances of the same morpheme if their distributions do not overlap.

(iii) Not all morphemes are segmental, i.e zero morpheme

The above analytic principles will help a linguist in identifying the morphemes in the language. Say that you have broken a clock and taken it apart, and now you have to put it all the little pieces back together. You could always go by trial and error, but the most efficient way would be to have some theory of how the clock goes together. Synthesis really involves theory construction. The analytic principles were taken from

Nida’s (1949; revised edition 1965) morphology.

The theoretical framework chosen were the analytic and synthetic approaches to morphology but other frameworks were also reviewed before we finally choose the analytic and synthetic approaches. Other frameworks reviewed include item-andarrangement. Item-and-process, and word and paradigm.

Hockett (1954:25) cited in Malmkjær (2002) distinguishes between two approaches to morphology which he calls itemand-arrangement and item-and-process. Both are associated xxxiii

with American structuralist linguistics, codified by Bloomfield

(1933), but they continue to be important today.

Item-and-arrangement grew out of the structuralist’s preoccupation with word analysis, and in particular with techniques for breaking words down into their component morphemes, which are the item. Morphology is then seen as the arrangement of these morphemes into a particular order or structure. For example, Books result from the concatenation of the two morphemes book and –s. In its simplest form, this way of analyzing word forms treats word as if they were made of morphemes put after each other like beads on a string; it is also called morpheme-based morphology.

Item-and-process, as its name suggests, is an approach to morphology in which complex words result from the operation of processes on simpler words. If we are working with an itemand-process framework, we might say that books result when the lexeme book undergoes the function ‘make plural’. In regular cases, this function will add the segment /-z/ which is realized as /-s/ after most voiceless segments and as / z/ after xxxiv

sibilants and affricates. It is also called lexeme-based morphology.

Item-and-arrangement and item-and process are almost equivalent to one another mathematically. Everything that you can express in item-and-arrangement can be expressed in itemand-process and vice – versa.

These two approaches were not chosen because; the approach does not apply to the language being worked on. They are suitable for languages with good use of affixation and inflectional languages which the Yiwom language is not.

The word and paradigm approach is an approach to morphology many will be familiar with from school-book descriptions of Latin grammar and the grammar of some modern European languages. Word and paradigm has a longestablished history, going back to ancient classical grammars.

In this approach, the word is central and is the fundamental unit in grammar. Word and paradigm which is called WP retains a basic distinction between morphology and syntax.

Morphology is concerned with the formation of words and syntax with the structure of sentences, central, therefore to xxxv

word and paradigm is the establishment of the word as an independent, stable unit. Robins (1959) offers convincing criteria for words and argues that word and paradigm is an extremely useful model in the description of languages. Word forms sharing a common root or base are grouped into one or more paradigms. Paradigm categories include such things as number in English. Word and paradigm is particularly useful in describing fusional features in languages.

The word and paradigm approach is of less use in describing certain types of language. To be able to use any of the approaches mentioned, a linguist has to be familiar with a language and its formation of words which the analytic and synthetic approach does not need. xxxvi

CHAPTER TWO

SOUND INVENTORIES AND SOUND PATTERNS IN YIWOM

2.0 INTRODUCTION

This chapter is on sound inventories and sound patterns in Yiwom language. This includes a brief review of the phonological concept of the language including the sound inventory, tone inventory, syllable inventory.

2.1 SOUND INVENTORIES IN YIWOM

Sounds are significant if they constitute difference in meaning of words in language. These significant sounds are referred to as phoneme. Phonemes are family of sounds which are related in character, they are used in such a way that one cannot occur where others occur.

Gimson (1980:47) in “An introduction to the pronunciation of English” acknowledged that phoneme is the smallest contrastive linguistics unit that brings about change in meaning of words in a language. Phonemes are also the sounds in a language. The sounds in Yiwom language include:

Consonants xxxvii

They are sounds produced with total or partial obstruction in the vocal tract. Consonant can be defined in terms of both phonetic and phonology. Phonetically, they are sounds made by a closure or narrowing in the vocal tract so that the airflow is either completely blocked or so restricted that audible friction is produced. From a phonological point of view, consonants are those units which function at the margins of syllables either singly or in clusters. Yiwom language has twenty-eight consonants.

Vowels

Phonetically, vowels are sounds articulated without a complete closure in the mouth or a degree of narrowing which would produce audible friction. The air escapes evenly over the centre of the tongue phonologically; they are those units which function at the centre of syllable. Yiwom language has the seven vowel system and no oral nasal was found. The oral nasal found were as a result of the phonological process called nasalization xxxviii

Stops

Implosives

Fricatives

Affricates

Nasals

Tap/flap

Laterals

Approximants m

P b

b f v t d s z

Dз n r/ l

r Palatal

η ŋ

j k g gb k

γ

w

Figure 2: Consonant Chart of Yiwom k w g w h

Front

High i

Mid-high e

Central

u

o

Back xxxix

Mid-low ε

Low a

Figure 3: the oral vowel chart of Yiwom

Yiwom language does not have nasal vowels and all voweld which tend to be nasalized are as a result of the phonological process of assimilation that is when they occur before or after a nasal consonant, they tend to be assimilated.

SOUND DISTRIBUTION IN YIWOM LANGUAGE

Consonants sound distribution in Yiwom:

[p] Voiceless bilabial stop

Initial: pàk “mouth” pìpàl ta “arm” pìn “room” medial: xl

típ pa “tobacco” pákpìn “door” bìspaŋ “sunshine” final: kírép “fish”

∫íép “tree”

Kúlùp “bag”

[b] voice bilabial stop

Initial: bàŋ “mat” bùk “thatch” bwàì “money” medial: lìbak “saliva” jàbà “banana” dìmbát “hoe” xli

[t] voiceless alveolar stop#

Initial: twótìk “hair” ta “hand” tuk “soup” medial: mùtòŋ “wine” jέmta “axe” fùrtù “mosquito” final: wót “breast” fat “ashes” kút “wind”

[d] voice alveolar stop

Initial: dí “word” dúŋ “lie(s) dip “sell” medial:

∫ìdá “pepper” xlii

jìdìŋ “charcoal”

àdá “matchet”

[k] voiceless velar stop

Initial: kúr “tortoise” kεp “vulture” kúŋ “leopard” medial: zàki “donkey” jέlkwa “maize ” t

úkú∫í “basket” final : wàk “snake” pàk “mouth” lúk “house”

[g] voice velar stop

Initial: gìwám “jaw” górò “kola nut” gíp “short” xliii

medial: gùgùl “nail” rógò “cassava”

γámgàŋ “palwiner”

[gb] voice labio-velar stop

Initial:

Gbăk “leg”

Gbìjàk “vomit”

Gban “pour”

Gbat “pull”

[k w ] voiceless labialized velar

Initial: k w úám “guinea fowl” k w n “three” k w ó “weep” medial: jέlk w a “maize ” kiέrk w a “groundnut”

[g w ] voice labialized velar xliv

g w ál “crab” gùg w á “duck”

[b] Voice bilabial implosive

Initial: bám “ear” bέ “thing” bέ kàγá “goat” bíl “horn”

[k] voiceless velar implosive

Initial: ké “head” kén “salt” medial: hakε “big”

[f] voiceless labio-dentals fricatives

Initial: frìm “knee” fím “cotton fat “ashes medial: xlv

kífír “rubbish heap” flέpfíl “abuse” tra flù “twenty”

[v] voice labio-dental fricative

Initial

Vùvùk “grass”

Vùk “bush”

Vùwòr “river”

Vìjiŋ “turn around”

[s] voiceless alveolar fricative

Initial:

Sìm “skin”

Sám “yam”

Sùr “ookra”

Medial:

Kàsúwá “market”

Bìspaŋ “sunshine” xlvi

Pàsí “small”

Final: lis “tongue” bìs “sun” bús “he-goat”

[z] voice alveolar fricative zàki “donkey” nzìŋ “story”

[∫] voiceless palate-alveolar fricative

Initial:

∫έm “blood”

∫íép “tree”

∫ît “cooking”

Medial: t

úkú ∫í “ basket ” tam∫àl “dance”

[γ] voice velar fricative

Initial:

γέs “teeth”

γak “stomach” xlvii

γεs “bone” medial: mìγέr “oil” bέ kàγá “goat” mùγέn “bee”

[h] glottal fricative medial: bùh mjír “needle” níhέt “heavy”

[dЗ] voice palate-alveolar affricate

Initial:

dЗír “rope” medial rídЗìja “well”

[m] bilabial nasal

Initial: mìγέr “oil” mor “millet” mús “cat” xlviii

medial: dìmbát “big hoe” jέmta “axe” lèmú “orange” final: sám “yam” rìm “beans” fim “thread”

[n] alveolar nasal

Initial: niŋ “sea” n k “work” nlin “hawk” final: pìn “room” fin “grinding stone” kán “uncle”

[η] palatal nasal

Initial:

ηjuwa “seed” xlix

ηjóŋ “cold”

ηjìn “show” medial:

∫íép ηjáŋ wùs “firewood”

[ŋ] velar nasal

Initial: ŋγa “refuse” ŋγεs “grind” ŋgak “drum” medial: jàŋgìjè “back” jíŋkíe “egg” baŋlúk “husband”

Final: kúŋ “leopard” k ŋ “chicken” klàŋ “war” l

[r

] alveolar tap

Initial:

rídЗìja “well” rìm “beans” ru “enter”

medial:

pírí “horse” krùm “person” pró “four”

final:

tír “in-law” kir “fear” jεr “thorn”

[l] alveolar lateral

Initial:

lis “tongue” lija “meat” lóŋ “spear” li

medial:

dìlìm “bark of tree” kòlé kòlé “boat” klàŋ “war”

final:

jùàl “thigh” jiεl “smoke” tεl “ask”

[j] palatal approximant

Initial:

jìn “elephant” jit “eye” jìdεt “sleep”

medial:

pija “white” fíját “spit” míjár “return”

[w] labio-velar approximant

lii

Initial:

wùs “fire” wàk “snake” wu “black”

medial:

twótìk “hair” tuwa “shoe” tuw n “dream”

Vowel distribution in Yiwom:

[i] high front unrounded

Medial:

jit “eye” pìn “room” dìk “build”

final:

fì “blow” mí “one” kí “new” liii

[u] high back rounded

Medial: tuam “taste” mùt “die” tuk “kill” final: dù “sleep” ru “enter” tu “run”

[e] mid-high front unrounded

Medial: dedil “play” lèmú “orange” dier “road” final: lè “give birth” nlìjè “louse” kòlé kòlé “boat”

[o] mid-high front rounded liv

Medial: mor “millet” górò “kola nut” rógò “cassava” final: so “eat” pró “four” túwó “witch”

[ε] mid-low front unrounded

Medial: dέm “make” sεl “give” tεl “ask” final: trε “laugh” tέ “sheep” hakε “big”

[ ] mid-low back rounded medial: w p “rainy season” lv

n k “work” b tik “cloth” w ŋ “song”

[a] low unrounded

Medial: tar “moon” fat “ashes” ját “bird” final: lá “cow” má “farm” tra “ten”

2.2 TONAL INVENTORY

Tone is a term used in phonology to refer to the distinctive pitch level of a syllable. In some languages in the world use pitch patterns to build morphemes in the same way consonant and vowels are used to build morpheme, languages where word meanings or grammatical categories are dependent on pitch level are known as tone language. Tone is the use of pitch in lvi

language to distinguish lexical or grammatical meaning that is to distinguish or inflect words.

According to Pike (1948:43)cited in Welmer (1973) “Tone is a language having significant but contrastive pitch on each syllable. Welmer (1973:80) defined tone as when segmental phonemes and non-segmental phonemes enter into the composition of some morpheme. All verbal languages use pitch to express emotional and other paralinguistic information, and to convey emphasis, contrast and other such features in what is called intonation, but not all languages use tones to distinguish words or their inflections, analogously to consonants and vowels. At least 50 percent of world’s languages employ tone to some extent.

For a language to qualify as a tone language, at least two level tones must be attested. There are two types of tone which are:

- Registered Tone Systems

- Contour Tone Systems

Registered Tone: lvii

These are tones that maintain level pitch. In other words, they are languages in which most of the tone can be described in terms of points within a pitch range. In an ideal register tone, the tones have level high, mid or low pitch. They are almost pure notes. The pitch hardly ever goes up or down during the production of a particular tone. In register tone languages, tones marking lexical items are comparatively steady. This is a language in which the majority of syllables maintain the same level or register. Register tones are called simple tones. In many register tone systems, there is a default tone, usually low in a two-tone system or mid in a three-tone system, that is more common and less salient than other tones. We have the high [/], mid [-] and low [\] tones under register tones.

Contour Tones:

These are tones involving gliding movement. A contour tone is a combination of two more basic tones such as a falling tone made up of a high tone and a low tone, or a rising tone consisting of a low tone followed by a high tone. Sometimes, a contour tone cannot be broken into a sequence of two tones, but when inspected can still be proven to act like two lviii

consecutive tones. In a contour language, the essential feature is changing pitch, such as rising, falling, dipping, or level. There are languages that combine register and contour tones. Yoruba have phonetic contours, but these can easily be analyzed as sequences of register tones, with for example sequence of highlow /áà/ becoming falling [â], and sequence of low-high /àá/ becoming rising [ă]. The distinction between contour and register tone languages is not absolute. Most systems display some of the qualities of the two types. Like the Yiwom language.

The language displays the quality of both the register and contour tone e.g.

Register tone: high [/]

Ké

KÍrεp

Túkú í

‘head’

‘fish’

‘basket’

Mid [-]

Fat

LIja

NlIn

Low [\]

‘ashes’

‘meat’

‘hawk’ lix

B tÌk ‘cloth’ mÌrεr ‘oil’ gbIjak ‘vomit’

Contour tone:

Rising tone [ ] jĭt ‘eye’ gbăk ‘leg’ bŭk ‘dust’

The falling tone was not found in the data collected and so it cannot be stated as being in the language.

The status of tone in Yiwom language is that it is use as a suprafix i.e. it is use to differentiate between words of the same spelling and to make the word readable for non speakers of the language.

2.3 SYLLABLE INVENTORY

Syllable is a unit of an utterance that can be utter within a breadth. Syllable represents a level of organizations of the speech sounds of a particular language. It is a muscular contraction in the chest which corresponds to the production of a syllable that is each syllable on this view involves one burst of lx

muscular energy. Syllable is a unit of pronunciation typically larger than a single sound and smaller than a word. a syllable corresponds to a chest pulse or initiator burst, that is a muscular contraction in the chest. On this view, a syllable is uttered within a chest pulse, a word may be pronounced

‘syllable at a time’. A syllable consists of an onset, a nucleus which is the peak and tone bearing unit of syllable and the coda. The nucleus is the compulsory part of syllable; it may and may not have an onset and a coda.

The nucleus is always a vowel, while the onset and coda are always consonant. Any consonants preceding the nucleus are said to be in the syllable onset, and those following the nucleus make up the coda. Together, the nucleus and coda form a constituent known as the rhyme. So in the Yiwom word: tím [tÍm] ‘name’

The onset is the consonant [t], the nucleus is the vowel [I] and the coda is the consonant [m] and both [I] and [m] form the rhyme. This can be representing as a tree structure where a syllable is represented with the Greek sigma . lxi

Onset

Consonant Nucleus

Rhyme

Coda

Vowel Consonant

Therefore, the word [tím] meaning “name” will be drawn on the tree diagram as:

Onset

t Nucleus

i

Rhyme tim means “name” in Yiwom

Coda

m lxii

This language allows consonant clusters that are it allows the sequence of consonants to follow each other immediately in a word. Example includes: bùhòmyír [buh mjIr] bwàì [bwaI]

‘needle’

‘money’ nlìyè [nlije] ‘mouse’

The words above have two consonants following each other sequentially without any vowel separating them. The language is also both an open syllable and a closed syllable language.

Open syllable is a language that does not allow consonant to end words in the language, that is there is no coda while closed syllable allows consonant to end word in the language and

Yiwom languages allows both consonant and vowel to end words in it. For example: kwó [kw ] nà [na]

‘keep’

‘see’ kír [kir] bìlàm

‘fear’

[bilam] ‘lick’ lxiii

The language also allows for different types of syllable which includes monosyllabic, disyllabic and polysyllabic.

Monosyllabic is a word with just one syllable. Example: dí [di] ‘word’ is a CV word dwòm [dw m] ‘tail’ CCVC tìs [tis] ‘male is a CVC word.

Di-syllabic is a word with two syllables e.g.

Lèmú [lemu] ‘orange’ le-mu, CV-CV yúwól típpa

[juw l] ‘guineacorn’

[típpa] ‘tobacco’ ju-w l, CV-CVC tip - CVC, pa- CV

Polysyllabic is a word with more than two syllables e.g. mbróm kwún [mbr mkw n] ‘seven’ m-br m-kw n

C-CCVC-CCVC mbróm pùwàt [mbr m puwat] ‘nine’ m-br m-pu-wat

C-CCVC-CV-CVC lxiv

2.4 BRIEF REVIEW OF PHONOLOGICAL CONCEPT IN

YIWOM LANGUAGE

One general view, which linguists admit of language, is its complex nature. This is why the structural linguists describes language as a “a system of systems” or set of inter-related systems having both the phonological (sound) and the grammatical systems (Dinneen, 1966:8).

Each of these systems has its proper units of permissible combination and order. From these two systems, we can isolate two planes of language analysis which linguists generally acknowledge: phonology and grammar (Gleason, 1969 and

Tomori, 1977). Phonology deals with phonemes and sequences of phonemes while grammar is concerned with morphemes and their combination into words and larger units (Gleason, 1969).

This means that phonemes and morphemes are basic units in linguistics which makes it necessary to discuss phonology before morphology of a language.

Phonology essentially deals with the description of the systems and patterns of speech sounds in a language. It is based on a theory of what every speaker of a language lxv

unconsciously knows about sounds pattern of that language.

This is the study of sound systems and abstract sound units. It is the study of sounds as discrete, abstract elements in the speaker’s mind that distinguish meaning. Phonology is concerned with sound patterns of a language. It studies how sounds are strung together, how they function in a particular human language. George Yule (1985) submits that “phonology” is concerned with the abstract or mental aspect of the sounds in a language rather than with the actual physical articulation of speech sounds. Phonology is about the description of sounds in a language and also the rules governing the distribution of sounds. The concept of phonology is “phoneme”.

Phonology is the input while morphology is the output. It is necessary to first talk about the phonology concept of the

Yiwom language before talking about the morphological concept of the language. The phonological concept in the language includes the sound inventory, tonal inventory and the syllable inventory of the language. lxvi

CHAPTER THREE

MORPHOLOGY OF YIWOM LANGUAGE

3.0 INTRODUCTIONS.

This chapter is about the morphology of Yiwom language, the focus of our study. The chapter discusses types of morphemes function of morphemes including affixes in Yiwom.

It also examines words that are traditionally known as the parts of speech and in modern linguistics called lexical categories.

3.1 MORPHOLOGY AND MORPHEMES IN YIWOM

The term morphology is generally attributed to the German poet, novelist, playwright, and philosopher Joham Wolfgang

Von Goethe (1749 – 1832), who coined it early in the nineteenth century in a biological context. Its etymology is in Greek Morphmeans ‘shape’, form and morphology is the study of form or forms. In linguistics, morphology refers to the mental system involved in word formation or to the branch of linguistics that deals with words, their internal structure and how they are formed.

Allerton (1979: 47) said “morphology is concerned with the forms of words themselves. Morphology is the description of lxvii

morphemes and their patterns of occurrence within the word”.

In linguistics, morphology is the identification, analysis is and description of the structure of morphemes and other units of meaning in a language like words, affixes, and parts of speech and intonation/stress, implied context. Morphology is the branch of linguistics that studies pattern of word formation within and across languages, and attempts to formulate rules that model the knowledge of the speakers of those languages.

Morphology is the study of internal structures of words and how they can be modified. It is the formation and composition of words. It entails rules guiding the formation of meaningful words in a language. Morphology is concerned with the forms of words themselves. Most linguists agree that morphology is the study of the meaningful parts of words but there have broadly been two ways of looking at the overall role played by these meaningful parts of words in language. One way has been to play down the status of the word itself and to look at the role of its parts in the overall syntax. The other has been to focus on the word as a central unit, whichever way is chosen, all linguists agree that within words, meaningful lxviii

elements can be perceived. Morphology is the branch of grammar that focuses on the study of internal structure of words and of the rules governing the formation of new words in language.

Morphology is the study of the smallest meaningful unit of a language and its combination in forming a word. Crystal

(2008:314) defines morphology as the branch of grammar which studies the structure or forms of words, primarily through the use of the morpheme construct. According to Spencer and

Zwicky (2001:1) “morphology is at the conceptual centre of linguistics. This is not because it is the dominant sub discipline but because morphology is the study of word structure, and words is at the interface between phonology, syntax and semantics.

While syntax is concerned with how words arrange themselves into construction, morphology is concerned with the forms of words. In theories where the word is an important unit, morphology, therefore becomes the description of morphemes and their patterns of occurrence within the word (Allerton

1979:47). Morphology is the branch of grammar which studies lxix

the structure of forms of words, primarily through the use of the morpheme construct. It is traditionally distinguished from syntax, which deals with the rules governing the combination of words in sentences (Crystal 2008:314). The minimal meaningful unit of a word is the ‘morpheme’.

The morpheme is a minimal meaningful unit which constitutes a word or part of a word. it is the minimal unit of meaning or grammatical function. It cannot be further broken down or segmented into further small unit. Morpheme is the fundamental tool or unit of morphological analysis is the minimal meaningful unit of grammatical analysis.

Bloomfield (1926) describes the morpheme as a recurrent form which cannot in turn be analyzed into smaller recurrent forms. Hence any unanalyzable word or formative is a morpheme. It is the formal physical units which have a phonetic shape meaning morpheme will always have a shape and not abstract. It will always have a role to play in construction. Morphemes can be identified through the following principles of morphemic identification. lxx

1. Forms which have the same meaning and same phonemic form would constitute a single morpheme.

Jàl léh ‘my slave’

Jàl yong ‘our slave’ jàl ti ‘the slave’

Jàl mwò ‘chief’s slave’

The data above shows that the word ‘jàl’ has the same form throughout and the same meaning which is ‘slave’.

2. Forms which have the same meaning but differ in phonemic form may constitute a morpheme provided the differences are phonologically definable. khà tung híel ‘you sit down’ khè bèltu ‘you come here’ khie long tíng ‘you stand up’ kù bèltu sékpáktàk ‘come here, all of you’

The data above has ‘khà’, ‘khè’, ‘kù’, has the same meaning but different forms because ‘kha’ is the general meaning of you while ‘khè’ is use to refer to a ‘male’, ‘khie’ is use to refer to a ‘female’ and ‘ku’ is a ‘you’ in an object position. lxxi

3. Forms with same meaning but differ in phonetic form in such a way that the distribution cannot be phonologically determined constitute a single morpheme, if the forms are in complementary distribution. mùkrùm ‘men’ tríp ‘women’ bhal yínkíe ‘eggs’ baal run tuk ‘spirits’

The data above has words which we have the same meaning, they are all referring to plurality but in different phonetic forms.

Bloomfield (1933) defines morpheme as a linguistics form which bears no partial phonetic – semantic resemblance to any other form. Crystal (2008:313) defines morpheme as “the minimal distinctive unit of grammar, and the central concern of morphology. Its original motivation was as an alternative to the notion of the word, which had proved to be difficult to work with in comparing languages.

As with EMIC notions, morphemes are abstract units, which are realized in speech by discrete units, known as lxxii

morphs. The relationship is generally referred to as one of exponence or realization. Most morphemes are realized by single morphs. Some morphemes however, are realized by more than one morph according to their position in a word or sentence, such alternative morphs being called allomorphs”.

A meaningful set is a morph, the set of morphs of similar form, like meaning and complementary distribution make up a morpheme. Nida (1946:79) said that morphemes are recognized by different partial resemblance between expressions which enable us to identify a common morpheme.

Morphemes carry meaning. In linguistics, a morpheme is the smallest component of word, or other linguistic unit, that has semantic meaning, the term is used as part of the branch of linguistics known as morphology. A morpheme is composed of phoneme(s) which is “the smallest linguistically distinctive units of sound” in spoken language, and of grapheme (s) which is “the smallest units of written language” in written language. lxxiii

3.2

TYPES OF MORPHEME

Basically there are two types of morphemes which are free morpheme.

Bound morpheme.

3.2.1

FREE MOPHEME

The free morpheme can be divided into the lexical and functional morpheme. The free morpheme is a word by itself. It is independent. It exists in isolation. It does not have to be attach to other element to make meaning. Free morphemes can appear with other lexemes or they can stand alone as words of a language. Most root in English are free morphemes e.g. dog, man, laugh etc although there are a few cases of roots like – gruntle as in disgruntle that must be combined with another bound morphemes in order to surface as an acceptable lexical item. Any morpheme that forms a word is a free morpheme e.g. using different language for example.

Yoruba language wá “come” owó “money” ewúré “goat” lxxiv

olórun “God”

Hausa language

Zó “come”

Kúdí “money”

Àkúyà “goat”

Allah “God”

Igbo language

Bia ‘come’

Ego ‘money’

Ewu ‘goat’

Chukwu ‘God’

Yiwom language

Bέl “come”

Bwàì “money”

Bέ kàγá “goat”

Ná’án “God”

The lexical morpheme carries the content of the message conveyed. It belongs to a class with same lexical item like Noun,

Verbs, Adjective and Adverb. Any word that belongs to this class will automatically be a lexical morpheme. Lexical morpheme is lxxv

highly extendable and numerous, they are uncountable. They belong to the open class; you can add and create new items.

Functional morphemes show relationship between or among lexical morphemes. They don’t convey any lexical meaning. They are preposition, conjunction, interjection. They are very few and countable they belong to the closed and stable class. They do not take affixes and have high frequency of occurrence.

Functional morphemes generally perform some kind of grammatical role, carrying little meaning of their own.

Functional morphemes are reciprocally exclusive, the use of one excludes the other. There is no creation or addition of new members.

3.2.2

BOUND MORPHEME

Bound morpheme as the name inclined is bound. It does not occur in isolation, it is dependent. For it to exist, it has to affix itself to another morpheme. It cannot occur alone, it must be attached. But it is meaningful. It gives additional meaning when attached or derivational. In morphology, a bound morpheme is a morpheme that only appears as part of a larger lxxvi

word. They only appear together with other morphemes to form a lexeme. Bound morphemes are generally regarded as affixes.

Affixes are usually three types at the segment level: prefix, infix and suffix. Affixes are bound morpheme attached to other words. In this sense, prefix, infix and suffix are all bound morphemes.

A Prefix is a bound morpheme that precedes the root morpheme in a word. It occupies the initial position of the word and is usually attached at the beginning of a free morpheme.

Examples in Yiwom language are

Yoruba language

àìje ‘not eat’

àìmu ‘not drink’

àìsun ‘not sleep’

Hausa language

Màìgídá ‘owner of house’

Yárúwá ‘son of mother’

Yárbánzá ‘bastard’

Yiwom language;

Krúm ‘person’ mùkrúm ‘people’ lxxvii

wong ‘song’

Run tìk ‘spirit’ mangwong baal runtìk

‘sing’

‘spirits’

Suffixes are bound morphemes that occur after the root morpheme. A suffix occurs at the word final position. That is, it is usually attached to the end of a word e.g.

Yiwom language

Yán ‘child’

Yèm ‘iron’

Khé ‘head’ yáróng ‘children’ yèmta ‘axe’ khéen ‘forehead’

Infixes are bound morphemes that occur in the roots. It breaks root into two. Infixes occur inside the free morpheme or between two free morphemes. It should be noted that not all language attest infixation. Yiwom language also like many other languages does not attest infixation.

Bound morpheme is a term used as part of the classification of morphemes, opposed to free, one which cannot occur on its own as a separate word (Crystal 2008:59)

3.3

FUNCTIONS OF MORPHEMES.

Morphemes perform both derivational and inflectional functions. Those that perform derivational lxxviii

function are referred to as derivational morpheme while those that perform inflectional functions are referred to as inflectional morphemes.

3.3.1

INFLECTIONAL MORPHEMES

Inflectional morphemes are bound morphemes attached to a base. That are purely grammatical markers, they are attached to give information like tense, case, gender, number etc. it express grammatical relation.

Inflectional morphemes modify a word’s tense, number, aspect and so on, without deriving new word or a word in a new grammatical category. They modify the grammatical class of words by signaling a change in number, person, gender etc but they also not shift the base form into another word class.

Inflectional morphemes are those affixes which primarily mark paradigmatic relations among grammatical elements in a language- a paradigm being the system of morphemes variations which is correlated with parallel system of variations environment (Francis, 1967). More specifically, inflectional morphemes result in changes in the form of a word to indicate lxxix

strictly grammatical relationship (cf, Mathews, 1974).Examples includes:

Yiwom Language

Khé ‘head’

Yèm ‘iron’ khéen ‘fore head’

Krúm ‘person’ mùkrúm ‘people’ yèmta axe

3.3.2

Kwo you (pl.) yikwo yours (pl.)

Ko them yiko theirs

DERIVATIONAL MORPHEMES

Derivational morphemes are used in creation of new words with new meaning. They are very productive as they are used in creation of any word. They are attached to the root because they are bound morpheme. They could change the lexical class that the root belongs to and it may not.

Derivational morphemes can be added to a word to create

(derive) another word. They modify a word according to its lexical and grammatical class. They result in more profound changes on base are derived from the use.

Derivation is the reverse of the coin of inflection. Like inflectional, it consists in adding to a root or stem an affix or lxxx

affixes. But while new inflections occur only very slowly over time, new derivational affixes seem to occur from time to time.

Derivational affix function to make new words.

Yiwom language does not have derivational morphemes based on the data collected and so the examples of derivational morphemes will not be cited here.

According to Essien (1990:27), cited in Malmkjær (2002) two broad divisions of morphological study include lexical and inflectional morphology. Lexical morphology leads with word formation process such as affixation, back formation, blends, suppletion, compounding etc. while inflectional morphology, on the other hand, marks grammatical categories like number, person, gender, case, tense, mood, voice and aspect.

Another function of morpheme is that it assists in removing any ambiguity especially in the case of tense and number. It also helps in knowing about events that happened prior to the time of speaking or current events and to know the particular number of human or animals that is being talked about. lxxxi

Morphemes combine to form words within one of the word classes. All free morphemes exist within a word class. Each word class incorporates words that all perform a similar function, so, bound and free. Morphemes combine to create words within the word classes. In this sense, the word classes discovered in Yiwom language will be discussed below.

3.4

NOUN

According to Crystal (2008:333), Noun is a term used in the grammatical classification of words, traditionally defined as the name of a person, place or thing; Nouns are generally sub classified into common and proper types and analyzed in terms of number, gender, case and countability.

Nouns are defined as belonging in the lexical category ( open word class) a word or, a group of words such as the name of a person, place, thing or activity, quality or idea. It can be used as the subject or object of a verb or the object of the preposition, head of the noun phrase, and is preceded by a determiner and/or adjective and/or noun modifier.

Nouns are a word that performs the functions of naming in the sentence. We can identity them of we consider functions lxxxii

they perform. The words classified must be used in context. The major function of noun in any language is “Naming”. Basically nouns are names. It is the basis of most modern words in linguistic. The list of things that are named may be a little restricted. Noun is a name of person, animal, places or things but it can be enlarged to names of exercise, activities, process, and concept and ideas e.g.

Líyá ‘meat’

Bìs ti fit ‘the sun rises’

Sun the rise

Pìn ‘spoon’

Múwòt ‘woman’

We have different classes of noun which includes proper nouns, common nouns, countable nouns, uncountable nouns, concrete nouns, Abstract nouns among others.

3.4.1 PROPER NOUN

Proper nouns are nouns that refer to specific entities. A proper noun is the name of a person, place or thing. It is personal to a particular people. It refers to a particular thing and not common thing; it is the opposite of common noun. A lxxxiii

proper noun always starts with a capital letter especially to show their distinction from common nouns. Example include

Kámlóng

Tíslèt

Mináán, which are names of individuals.

Pituop

Gárkáwá

Mìkáng, names of places

3.4.2 COMMON NOUN

Common nouns refer to general, unspecific categories of entities. It denotes concepts, names of things. It doesn’t have a restricted membership. Whereas ‘Nebraska’ is a proper noun because it signifies a specific state, the word state itself is a common noun because it can refer to any of the 50 states in the

United States. ‘Harvard’ refers to a particular institution of high learning, while the common noun university can refer to any such institution. Examples include: tìs ‘man’ líyá háak vùk ‘animal’ vùwòr ‘river’ lxxxiv

yán lá

‘child’

‘cow’

3.4.3 COUNTABLE NOUNS

To linguists, these count nouns can occur in both single and plural forms, can be modified by numerals, and can cooccur with quantificational determiners like many, most, more, several etc. just like the name implies, it is countable which means it can be counted. Examples include.

Tìs ‘man’ mùkrúm ‘men’

Múwòt ‘woman’ trip ‘women’

Bak ‘foot’ bak flù ‘two feet’

Lúk ‘house’ lúk zèzàng ‘many house’

3.4.4 UNCOUNTABLE OR MASS NOUNS.

Conversely, some nouns are not countable and are called uncountable nouns or mass nouns. They cannot be counted, examples includes:

Hààm ‘water’ mìhèr ‘oil’

Mùtòng ‘wine’ lxxxv

Tuk ‘soup’

Shèm ‘blood’

3.4.5 CONCRETE NOUN

Concrete nouns are nouns that can be touched, smelled, seen, felt, or tasted. They are tangible entities, things that can be seen, hold and touch; concrete nouns can be perceived by at least one of our sense. Example includes; ghyék ‘stone’ hàt ‘dog’ fím fíen

‘cotton’

‘grinding stone’ túkúshí ‘basket’

3.4.6 ABSTRACT NOUNS

Bossmann (1996:3) says “in contrast to concrete nouns, abstract form a semantically defined class of nouns that denote concepts (psyche), characteristics (laziness), relationships

(kinship), institutions (marriage) etc. but not persons, objects, substances or the like. lxxxvi

Abstract nouns refer to concepts, ideas, philosophies, and other entities that cannot be concretely perceived. They cannot be seen, hold but can be felt. Example includes; kír ‘fear’ khétím ‘hunger’ háám tùk ‘thirst’ puwet ‘sickness dwomba ‘lust’

3.5 VERB

According to Crystal (2008:510), verb is a term used in the grammatical classification of words, to refer to a class traditionally defined as ‘doing’ or action words.

Luraghi and Parodi (2008:148) say verbs may inflect for tense, aspect, voice, modality and some agreement categories such as person, number and gender, prototypically, the indicate dynamic entities, such as actions or processes. lxxxvii

Verbs specify what we are saying about something. They may be transitive, intransitive or ditransitive. They may indicate state or events of affairs, state (know, love) activities (walk, sleep)

Verbs are defined as also belonging to the lexical category

(open word class); a word or a group of words that is used in describing an action, experience or state. It is the head of the verb phrase. Verbs are predicators of the sentence. The verbs in a sentence will come after Noun in a statement. We have transitive and intransitive verb, Examples includes;

Man

Nà

‘walk’

‘see’

Klàng ‘fight’

Mìhèr ‘steal’

3.5.1 TRANSITIVE VERBS

The action in the verb is transferred to another entity and so it requires an object. Examples:

Aa nà ni

I see her

Muh da jàl ti lxxxviii

We call slave the

We call the slave

Aa wa dip kírép

I want buy fish

I want to buy fish.

3.5.2 INTRANSITIVE VERB

Intransitive verb does not require any object because its action is not transferred to any other entity. It only takes adjunct for additional meaning. Examples: yáni pi pèt

Child is ill

My child is ill.

Ni man di bélli

He walks and come

He is coming.

Khe long tíng (m)

You stand up

3.6 ADJECTIVE lxxxix

According to Crystal (2008:11), a term used in the grammatical classification of words to refer to the main set of items which specify the attributes of nouns is called adjective.

Luraghi and Parodi (2008:148) say adjective prototypically indicate qualities, and most frequently serve as attributes of nouns.

Adjective comes before or after the noun. Adjective is a qualifier, it qualifies the noun, and it gives additional information about the noun. It tells you more about the features of a noun. It shows quality; qualifies a noun and also quantity.

All colors are adjectives; it also gives information about size.

Examples:

Dóng

Nyóng

‘good’

‘wet’

Díngyéng ‘tall’

Adjectives denoting age: this includes

kí

Tús

Fùòlé

‘new’

‘old’

‘old person’

Adjectives denoting colour: this includes xc

Wu

Pìyá

Lah

‘black’

‘white’

‘red’

General adjective:

Nuwa ‘hot’

Pàsí ‘small’

Krak

Kpém

3.7

PRONOUN

‘hard’

‘full’

Crystal (2008:391) defined pronoun as a term used in the grammatical classification of word, refereeing to the closed set of items which can be used to substitute for a noun phrase or single noun.

Luraghi and Parodi (2008:148) say that items in this word class usually stand for nouns. Infact, pronouns have the same distributional properties phrase but do not have a lexical meaning. Their reference is indicated either by a noun they stand for, in which case they are said to be anaphoric, or by extra linguistic factor when they refer to an entity external to the text and function as duties. xci

Pronouns are words used in place of noun. Pronouns function in all the positions of noun. There are different types of pronoun; we have personal pronoun, reflexive pronoun, possessive etc.

3.7.1

PERSONAL PRONOUN

This is a replacement of co-referential noun phrase in preceding clauses. E.g.

Aa ‘I’

Khaa ‘you’ (singular)

Nie

Ko

3.7.2

‘tie’

‘they’

REFLEXIVE PRONOUN

This will replace a co-referential noun phrase normally within the same finite clause e.g.

Hien ndulaa ‘myself’

Nduk ka ‘yourself’ (singular male)

Ku piyat ‘yourselves’ (plural)

Min piyang ‘ourselves’

3.7.3

POSSESSIVE PRONOUN xcii

It will replace a co-referential item in the same clause or neighboring clause e.g.

Yini ‘mine’

Yikwo ‘yours’ (plural)

Aa yong ‘ours’

Yi khie ‘yours’ (singular female)

3.7.4

INTERROGATIVE PRONOUNS

These types of pronouns are question e.g. ami ‘what’ ani wo

‘where’

‘who’ ngwo ‘which’

3.8

ADVERBS.

Aronoff and Fudeman (2005:209) defines adverb as a word that modifies a verb, an adjective, another adverb, a preposition, or a larger unit such as phrase or sentence. It often expresses some relation of manner or quality, time or degree.

Crystal (2008:14) defined adverb as a term use din the grammatical classification of words to refer to a heterogeneous xciii

group of items whose most frequent function is to specify the mode of action of the verb.

Luraghi, and Parodi (2008:148) says adverbs modify verbs, adjectives and clauses, manner, place , time etc.

Adverbs give additional information about a verb. It tells how actions are performed. We have adverbs of place, time, manner etc. examples includes the following

Aa wát kàsúwá

I go market

“I am going to the market “ khe béltu

You come here (m)

Khi béltu

You come here (f)

Aa wát máni

I am going to my farm

These examples are adverbs of place.

Adverbs of time

Ni bél khe khèjémíníe xciv

He came yesterday

Ni man di bélli krintú

He is coming today

Khe demi ko wani rie

What do you do every day?

3.9

DETERMINERS

Determiners are not necessary for all nouns. Some nouns take determiners while some don’t. Nouns that have determiners must have these characteristics.

The rule that guide the use of determiner is that a common, singular and countable noun must be preceded or accompanied by one of the various determiners available in

English.

Give me water is correct while give me biro is incorrect, because it is ungrammatical, it breaks the syntactic rule.

Determiners behave like adjectives. They determine the kind of noun. They give some information about the land of noun used.

Example include

Ti ‘the’ xcv

Bìs ti ‘the sun’

Jàl leh ‘my slave’

Slave my

Mùkrúm tra ‘ten people’

People ten

Baal lúk ‘all the houses’.

All houses

3.10

NUMBER

Crystal (2008:335) defined number as a grammatical category used or the analysis of word classes displaying such contrasts as singular, plural, dual, mat. It has to do with either singular or plural. Languages like English make a distinction between singular and plural. In languages that are inflectional, the noun will be inflected with number.

Subject

1 st person singular Aa

2 nd person singular Khaa (m)

Khie (f)

3 rd person singular Nie (m)

1 st person plural

Khie (f)

Min

Object

Hien

Khaa (m)

Khie (f)

Nie (m)

Khie (f)

Min xcvi

2 nd person plural Ku

3 rd person plural ko

Figure 4: pronoun table in Yiwom

Also we have ghàs pùwàt tooth five

‘Five tooth’ bám flù ear two

‘two ears’ baal lúk

Kwo

Ko

‘many house’

3.11 Preposition

Bussmann (1996:378) says preposition is an uninflected part of speech (usually) developed from original adverbs of place. Like adverbs and some conjunctions, prepositions in their original meaning denote relations of locality (on, over, xcvii

under), temporality (before, after, during), causality (because of) and modality (like).

Crystal (2008:383) says preposition is a term used in the grammatical classification of words, referring to the set of items which typically precede noun phrases to form a single constituent of structure. A preposition will relate to a verb in terms of location, condition, state. It expresses a relationship between two entity e.g.

I saw the man at the market.

The woman with the red skirt etc.

Yiwom language

Nu ‘with’

Yi ‘on’

Kihop ‘under’

Waji ‘above’

3.12 Conjunction

Crystal (2008:101) says conjunctions are words to refer to an item or a process whose primary function is to connect words or other construction. xcviii

Luraghi and Parodi (2008:149) also say conjunction indicates that a certain unit is connected with another unit, and belong to several types. Conjunctions are devices use to join two or more elements together. They are linking units that will join elements like phrases, words, sentences. It indicates either togetherness or separateness e.g.

Olu and Ola

The woman came but I did not see her.

Yiwom language:

3.13

Demu ‘and’

Wus ‘but’

LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY

Language typology is based on the assumption that

(Greenberg 1974: 54-55) the ways in which languages differ from each other are not entirely random, but show various types of dependencies among those properties of languages which are not invariant differences statable in terms of the

‘type’. The construct of the ‘type’ is, as it were, interposed between the individual language in all its uniqueness and the unconditional or invariant features to be found in all languages. xcix

The data provided by typological language studies show the limits within which languages can vary, and in so doing provide statements about the nature of language (Mallison and Blake

1981: 6).

Greenberg (1974: 13, n. 4) dates the first use of the word

‘typology’ in linguistics literature to the theses represented by the Prague school linguists to the first congress of Slavonic philologists held in 1928. Until then, classification of language was largely genetic, that is, it was based on the development of languages from older source languages and the only extensively used typology was morphological classification of language as approximately towards ideal types: isolating, agglutinating, fusional and polysynthetic (Wundt 1900).

Morphological typology is a way of classifying the language of the world that groups language, according to their common morphological structures. First developed by brothers Friedrich

Von Schlegel and August Von Schlegel, the field organizes languages on the basis of how those languages form words by combining morphemes. Morphological typology is the categorization of a language according to the extent to which c

words in the language are clearly divisible into individual morpheme.

An ideal isolating language is one in which there is a one to one correspondence between words and morphemes e.g.

China, Vietnamese.

Agglutinating is one which attaches separable affixes to roots so that there may be several morphemes in a word, but the boundaries between them are always clear. Each morpheme has a reasonably invariant shape e.g. Hungarian, Japanese,

Turkey.

An inflecting or fusional is one in which morphemes are represented by affixes, but in which it is difficult to assign morphemes precisely to the different parts of the affixes e.g.

Latin, Russian, Ancient Greek and Sanskrit.