File - Bruce Ballenger

advertisement

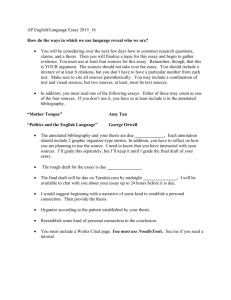

1 Dr. Bruce Ballenger Boise State University The College Research Paper: A Captivity Narrative Portland State University, April 2012 It’s now been about 25 years since the classroom failure that led me to wonder why the college research paper is like the bad uncle you’re forced to invite to the wedding. In the years since then, I wrote and published my dissertation on the assignment, published a few articles on the topic, and brought my textbook The Curious Researcher through seven editions. Since the research paper is taught across the curriculum, I thought this would be a great opportunity to look back and look ahead at the assignment and maybe offer a few ideas about how all of us who ask for research writing might do it more successfully. I’ve titled this talk a “captivity narrative.” I think to understand our struggles with teaching students research-based writing it’s helpful to see the ways in which the assignment has been a slave to assumptions that arise from the huge transformation of the American university at the turn of the century. I’ll talk about those assumptions in the next few minutes. But in addition to sharing the history of the research paper, I also want to highlight the ways in which it has been freed from captivity in the last decade or two, and how it can be re-imagined in the years ahead. First, a story. In the mid-eighties, when I began teaching writing to college students, I had student in my freshman English class named Jayne. She was a bright, talented writer— abilities that had little to do with me and my teaching—and I still have a faded photocopy of the 2 first essay she gave me, a personal narrative titled “The Sterile Cage.” In it, she tells the story of being diagnosed with bone cancer at the age of six, and after a fall, ending up in surgery to remove the tumor and to repair her broken bones. Jayne remembered waking up from surgery with her right leg suspended by a large steel cage, bars and pulleys and ropes and sandbags. “I couldn’t seem to see anything beyond my bed,” she wrote. “I couldn’t hear any sounds. I was in a sterile cage.” She ended her essay this way: “I lived in the ward room for three and a half months; I left the room only once when I got German measles and was quarantined in a private room for ten days. During those months it seemed like the world of home and family and friends I had left behind was no longer real—they were just shadows in memory. I saw my brothers only once…and my father I saw on Saturday and Sunday afternoons. And I hardly remember my mother being with me, although I know she came to visit me every day. She’d sit in the hardbacked chair beside my bed and knit while I colored or played with dolls, the monotonous clicking of her knitting needles ticking away the minutes. I’d look up from my playthings and see her quiet face; sometimes I’d catch a glimpse of what my mother used to be to me. More often, however, my mother seemed like a ghost of reality moving around my bed…Twenty years have passed and I’m still unable to define the vagueness and separateness I felt at that time in my life.” I quote at such length from Jayne’s essay not only because it’s such a pleasure to read such fine writing from a college student but because most of this fine writing—the fluency of the language, the insight, the voice—completely disappeared when she wrote a research paper 3 for me in the last five weeks of the course. I didn’t keep that paper. But I vaguely remember it had something to do with child psychology, a topic that might have been relevant to her personal essay. What I do remember—vividly—is how disappointed I was by Jayne’s research paper. What had happened, I wondered, to that wonderful writer of “The Sterile Cage?” This paper was dull, uninspired, and utterly predictable. The writer who had such a strong presence in her other essays was missing from this one. There was nobody home. I remember the conference in my office when we discussed her first draft. The conversation went something like this: What did she think of the paper? I asked. “Not much,” she said. Did she find it unfocused? “Sort of.” Did the paper sound lifeless? “Yes” Then she glared across the desk at me. “What do you want from me?” she said. “This is a research paper, goddammit. It’s supposed to be this way.” I came to understand this gap between what many of our students call “creative” writing—personal things like “The Sterile Cage”--and academic writing--pretty much anything 4 that involves facts—is an abyss of our own making. Granted, academic prose has its own conventions, and these sometimes include the illusion that a paper speaks rather its author. But I also know as a scholar that even the most formal academic writing is deeply subjective: it is driven by the questions that most interest us, which are quite personal, and even if we don’t write in the first person, we are present nonetheless in the way we control quotation, interpret what others have said, and define the territory we’ll explore. I also know that my colleagues are very “creative.” Academic inquiry is a creative enterprise in the true sense of the term. It’s an act of imagination. What might be true? That’s the question that keeps us up a night, which keeps us poring over a spreadsheet, analyzing a short story, or designing an experiment. But Jayne saw absolutely no connection between her personal essay and her research paper. The research paper was a genre that she thought she knew, and its essential qualities were that it must be “objective,” “original,” formally structured with a thesis sentence in the introduction, and done “correctly” according to the rules outlined by Kate Turabian, the woman who wrote the Manual for Writers of Researcher Papers. (Turabian, by the way, was the dissertation secretary at the University of Chicago, and the one who, among other things, made sure a thesis had the right-sized margins). This research paper bears little resemblance to what I’ve always understood to be the purpose for academic inquiry (and personal essay writing, for that matter): discovery. Our work is driven by questions, not answers. We don’t just argue or prove, we explore. How, then, had it come to this? How is it that when we tell students to write with research they think we are committing them to the academic equivalent of purgatory, which 5 my Catholic mother once described as playing an endless game of golf on a course with no holes? The angst associated with the research paper, by the way, stretches back to the form’s beginnings as an assignment, and seems nicely captured in this account by Robert Esch, who described it in a 1975 journal article on teaching the research paper. He writes that a few days before the deadline for the paper, a student approached him and said, “Mr. Esch, I had a dream about you last night.” She then described a dream in which Esch pushed a button for a trap door, through which the student fell into a basement room where he had trapped other university students, all of whom were working on research papers surraounded by “stacks of 3x5 and 5x 7 note cards.” The student then described the scene: “All of those people were trying to write the perfect research paper. Some of them I recognized. Others had been down there in that room for over 20 years, and no one had heard from them. “And do you know what you did when they finally turned in a paper you found acceptable?” “God knows, what?” “You stood them up against the wall and shot them.” My former student, Jayne, no doubt fantasized turning the gun on me. As I said at the beginning of this talk, I think one explanation for the sorry state of the research paper had to do with the history of the assignment. Back when I was working on my dissertation, I had the good fortune to be at the University of New Hampshire which had a large 6 and, back then, largely uncatalogued collection of composition textbooks from the 18th century to the present. So I set about looking for the first appearance of the assignment in a textbook. As far as I could tell, something called the “investigative theme” first appeared in Charles Baldwin’s A College Manual of Rhetoric when it was published in 1906. He was also the first one to bring on the curse of the note card (“small slips or cards”). For Baldwin, the investigative theme was—and wasn’t—like the research paper we see today. For one thing, it was not a separate genre but rather a form of exposition. In other words, there was no separate chapter in his book on how to write the “research paper.” He emphasized collecting facts in the library and compiling them in some “original” way. Baldwin warned, as we do these days, against the “paste pot and shears” method: just dropping and pasting facts into a paper. And yet the sample paper he includes in the College Manual of Rhetoric does just that. The topic was the “efficiency” of the Roman army and it was mostly a encyclopedic report that ends with the line “The Roman army was an efficient fighting machine.” By the 1920s, the research paper came into its own in ways that will seem entirely familiar to those of us in the 21st century. Composition textbooks started having a separate chapter on the research paper, along with advice on how to create notecards, cite materials, and use the library. There was, however, virtually no explanation about why a student should write a research paper in the first place other than learning research skills. It was just what college students do. I’d like to introduce a back story that helps explain the appearance of the so-called research paper in undergraduate education. As many of you know, the American university 7 was transformed in the late nineteenth century from what were once insular, homogenous, and exclusive colleges dedicated to preparing young white men for law, the Lord, and polite society. College was about cultivating character. Becoming learned. That changed dramatically when American professors were exposed to the German model of the university, which elevated the “research ideal” as a central purpose. The purpose of the university was to create knowledge not to simply distribute the “best” of what was already known to young men. Professors did research, and so did their graduate students. Because the tree of knowledge was a living thing, extending skyward from branches nourished by previous discoveries, scholars and graduate students started writing documented research papers. Pretty soon the idea that the research paper was an exalted form—the medium for reporting discoveries—trickled down to undergraduates. After all, if their graduate teaching assistants had to write the damn things, so should their composition students. Of course, at the heart of the research ideal is the notion that research papers report on original discoveries, things that add to the tree of knowledge. Though deep down no one really expected an undergraduate, much less a composition student, to do serious scholarly work, for a long time we kept on expecting it and the result was inevitable: the student research paper continued to disappoint us. “The research paper is embedded like a stone in the last third of the composition class,” one instructor lamented a couple of decades ago, “and we all hate it.” What’s interesting to me is that despite all this hand-wringing, there was very little discussion about what we hope to accomplish when we teach a research paper. It may be the most undertheorized writing assignment of all time. Ultimately, however, we had to grade these things, and in the absence of the kind scholarship lite that we secretly hoped for from our 8 undergraduates, we started to focus on things like format, proper citations of sources, note cards. Books on how to write research papers became technical manuals and skills guides, and rarely addressed the elephant in the room: What do we want students to learn from writing research papers? For 100 years, the answer was simple: research skills. This is what has kept Turabian in business all these years. But there are much easier ways to teach research skills than assigning 7 to 15 page research papers. Beyond skills, what do we want students to learn from research projects? I’d like to propose three answers to that question. Writerly approach. If we go back to the very beginning when the “investigative” or “source theme” first appeared as an assignment, it was a form of exposition written, like any essay back then, for a general audience. As library materials became more available, more information became available to writers. Naturally, this source of information became material to mine for any theme. In that sense, there is no such thing as a “research paper.” There’s just an essay that uses research. I wouldn’t call this a research paper at all, in fact, but a “researched essay.” We would assign a researched essay not to simply teach research skills but to help students see that any question that’s worth exploring should be explored by casting a wide a net, including information from research. Habits of mind approach. One of the great writing theorists, Ann Berthoff, once said that every writing assignment, from the first to the last and no matter how different, should involve certain “essential acts of mind.” These are methods of 9 thinking that penetrate the entire course curriculum and give it cohesion. For me, these essential acts of mind are based on how academics across the curriculum do scholarly inquiry, and they are things like the willingness to suspend judgment and tolerate ambiguity, the recognition that questions—not answers—drive the process, and most important, that the goal of inquiry is discovery. This means that the motive for research writing, at least initially, is to find out rather than to prove. To essay rather than to argue. In practice, this means that students choose to investigate something because they don’t know what they think, not because they already know what they want to say. Information literacy approach. We live, as one writer put it back in 2002, in a “radically different information universe.” Ten years later, people worry that even our computer storage may not be capable of keeping up with it. It’s a nobrainer, then, that one of the main purposes of research instruction should be what we’ve come to call “information literacy”: the ability to find, evaluate, and appropriately use information. This is a lifelong skill not just an academic one, and would seem to be the kind of thing we’d turn to librarians to teach. But there’s an important difference between information and knowledge. Information doesn’t have a context. It changes rapidly. It is “transmitted” and not “constructed.” Knowledge is slow-changing and is always created in context. In college, this context is the academic disciplines. And this is why it’s our responsibility—not just the librarians—to teach it. 10 I’d like to end my talk today by proposing 21st century alternatives to the conventional research paper that draw on these goals. What might these assignments look like? For anyone familiar with my text The Curious Researcher, you won’t be surprised by my pitch for what I call the research essay. This is an assignment whose purpose is exploratory rather than argumentative; we write an essay to find out rather than to prove. Writing an essay like this is, in my view, one of the best ways to teach those habits of mind I most associate with genuine inquiry: research driven by questions not answers, an acceptance that inquiry involves ambiguity and doubt and demands that one suspends judgment. But most of all, the research essay reinforces the idea that ultimately the aim of research is discovery. To find out. While we still might assign argumentative research, we’d also make room for essayistic research, perhaps as an assignment that helps students discover their argument. Just this week, the Writing Center at my university announced it was sponsoring a workshop on how to write a thesis sentence. Good idea. But I’d like to see them also sponsor a workshop on how to ask a good question. I think this is the research skill that we woefully neglect, and as a result, students see the thesis as a starting place, not a destination. So what we get is the academic equivalent of freeze dried food: everything is pre-cooked, and you just add hot water. Dream up and thesis, hunt for information that supports it, and let it steep overnight. Voila, a research paper! 11 Anyone who actually does research knows that this isn’t really research. It’s short order cooking. Research is initially driven by questions. And yet we don’t talk much about that. We talk about the importance of a thesis, and the required numbers of sources, and citing things in the APA. But if we were going to talk about what makes a good inquiry question what would we way? I had a student once who said to me that his research question was “Is Elvis Dead?” Another wanted to know, “Is Murphy’s Law real?” My instincts back then told me that these were both dead-end questions but I had a hard time explaining why. Now I think I could. Good questions don’t have simple answers. Good questions are on topics about which something has already been said. People other than the writer have a stake in the answer. And so on. But I’ve also been thinking about what distinguishes our students most from ourselves and others who might be experts on a topic students are interested in: Prior knowledge. We know what has already been said. We’re familiar with the controversies and the actors. We know the kinds of questions people ask in our disciplines. So this leaves students at a disadvantage. We expect them to do academic research on things that they know little about, and this changes everything. They not only have little experience knowing what kinds of questions to ask, they can’t understand some of the academic discourse we expect them to read. No wonder we’ve been disappointed by research papers for so long. When they don’t produce papers that offer some interesting insight, or that don’t use sources in a sophisticated 12 way, we swallow our disappointment and then resort to evaluating correctness. That’s a lot easier than teaching habits of mind or critical thinking or inquiry. What do we do about this prior knowledge deficit? One solution is not to ask for research papers until students are in upper-division classes in their disciplines. A better solution is to recognize that students will move through stages of knowing and our expectations should be adjusted to match those stages. Think about the process of coming to know that most of us experience when learning something new. In the beginning, we’re curious. Something catches our attention. Theorists tell us that curiosity is either “situational” or “personal.” Situational curiosity is an often short-term interest in something. We see or hear something that sparks our curiosity, things which are sometimes called “seductive details.” For example, my daughter once wrote a research paper about Britain’s King James largely because she heard he had an extraordinarily long tongue. “Personal interest,” on the other 13 hand, tends to be longer term. We see that learning something new might have some longerterm personal value. I think most of us who teach are convinced that our courses are valuable in that way, of course. The implication here is that when we want students to do research we should actively encourage them to find that personal meaning. I’m also guessing that this becomes much more difficult for students to feel when we assign research topics. Learning theorists also say that there is a strong relationship between knowledge of a topic and interest in it. In other words, a successful research project depends on some working knowledge that students may lack. What this suggests is in any course that requires a research paper we should scaffold the assignment, focusing first on asking students to develop that working knowledge. Another way to look at this is that whenever we develop a new interest in something, our first questions are always factual. What is known about this? These days, a factual inquiry often begins with the Web. What I’m suggesting, then, is that the first stage of knowing is simple information-seeking, some of which might be done online and some in the library. This information-seeking doesn’t produce research papers but it might lend itself to other forms. Here’s a slide for example of an infographic from National Geographic magazine. 14 I haven’t tried this but I can imagine creating an assignment in which students produce some kind of multimodal summary like this of some aspect of a topic they’re interested in. We might also ask for a series of PowerPoint slides that reports on what’s known, or perhaps an exploratory essay that tells the story of the search itself. I was interested in ____ and then I learned ___ and then, and then. In his sixties rant against the evils of the research paper, Ken Macrorie called this an “I-Search” paper. Only when students have a personal interest and working knowledge of a research topic can we begin to expect good questions, strong analysis, and persuasive arguments. 15 I’d like to return briefly to the question of questions. Here you can see that the stages of knowing about a topic one has little prior knowledge about begins with factual questions but then, with the benefit of knowing more, better, more researchable questions emerge: questions of policy, interpretive questions, hypothesis questions, and so on. So the second stage of instruction might ask that students move towards questions like these, and ultimately towards the real genres of writing that the questions lead to: proposals, critical essays, and so on. Because, you see, there is, finally, no such thing as a research paper. Never was. As Richard Larson pointed out some years ago, the research paper is a “non-genre.” Virtually any kind of writing can be informed by research, including creative writing. Research is, after all, not a genre but a source of information. The research paper was invented in the 1920s as a 16 crude imitation of the scholarship that professors and graduate students were doing. And along with it came largely unreasonable assumptions that undergraduates should do “original” research and write “up” to fellow experts like their teachers do. Since no one, deep in their hearts, really believed that, the research paper became—especially in composition—the most hated writing assignment in America. So maybe we should just abandon the term altogether. Let’s call the assignment “researched writing.” Or ask for genres that really do exist in the world: proposals, persuasive essays, reviews, ethnographies, and so on. And let’s put the central aim of researched writing back at the center of the enterprise: The experience of discovery. I use the phrase “experience of discovery” quite deliberately. Most undergraduates can’t be expected to add to the tree of knowledge in a discipline. But they can have the experience that most of us remember as one of the most rewarding in college: that moment, often late at night, in the wash of white light of a desk lamp, reading an article that opens our eyes to a world we didn’t know. “Wow,” we think to ourselves, “I don’t know what to make of this.” We pick up the pen and start scribbling, writing our way to understanding. 17