Postcolonial Belonging as an Ethic of Care Bindi MacGill Abstract

Postcolonial Belonging as an Ethic of Care

Bindi MacGill

Abstract

This paper explores the notion that an ethic of care is differentially expressed within pluralist projects of belonging (Yuval-Davis). In postcolonial contexts, belonging to a place is a constructed and socially constitutive political and moral project that is often highly contested.

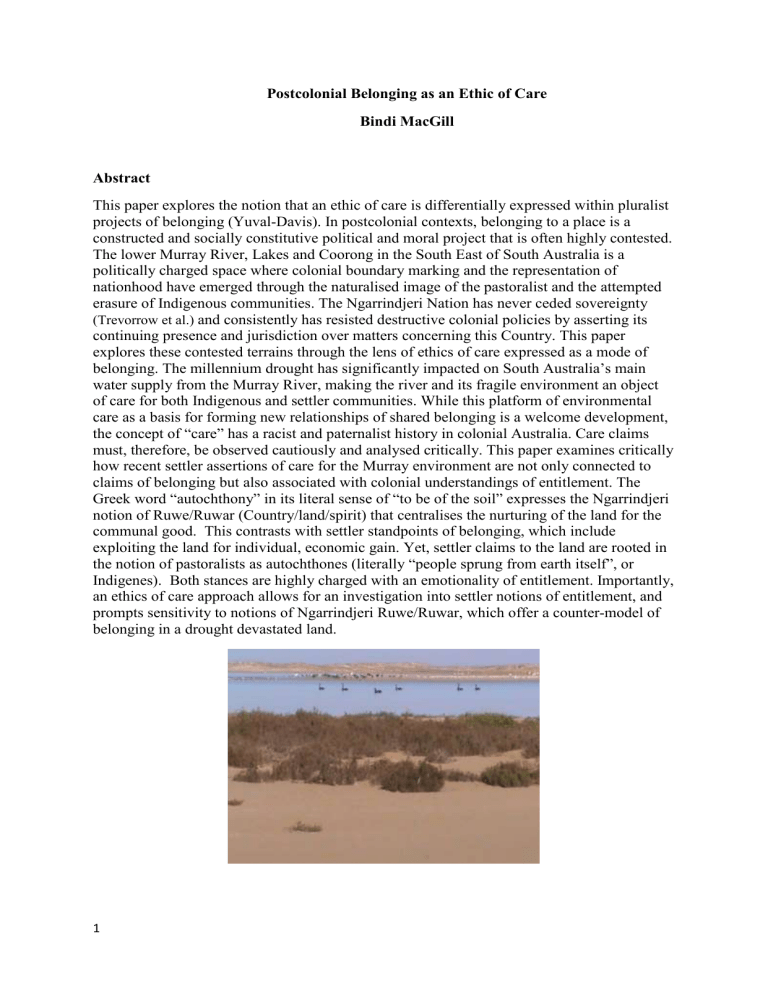

The lower Murray River, Lakes and Coorong in the South East of South Australia is a politically charged space where colonial boundary marking and the representation of nationhood have emerged through the naturalised image of the pastoralist and the attempted erasure of Indigenous communities. The Ngarrindjeri Nation has never ceded sovereignty

and consistently has resisted destructive colonial policies by asserting its continuing presence and jurisdiction over matters concerning this Country. This paper explores these contested terrains through the lens of ethics of care expressed as a mode of belonging. The millennium drought has significantly impacted on South Australia’s main water supply from the Murray River, making the river and its fragile environment an object of care for both Indigenous and settler communities. While this platform of environmental care as a basis for forming new relationships of shared belonging is a welcome development, the concept of “care” has a racist and paternalist history in colonial Australia. Care claims must, therefore, be observed cautiously and analysed critically. This paper examines critically how recent settler assertions of care for the Murray environment are not only connected to claims of belonging but also associated with colonial understandings of entitlement. The

Greek word “autochthony” in its literal sense of “to be of the soil” expresses the Ngarrindjeri notion of Ruwe/Ruwar (Country/land/spirit) that centralises the nurturing of the land for the communal good. This contrasts with settler standpoints of belonging, which include exploiting the land for individual, economic gain. Yet, settler claims to the land are rooted in the notion of pastoralists as autochthones (literally “people sprung from earth itself”, or

Indigenes). Both stances are highly charged with an emotionality of entitlement. Importantly, an ethics of care approach allows for an investigation into settler notions of entitlement, and prompts sensitivity to notions of Ngarrindjeri Ruwe/Ruwar, which offer a counter-model of belonging in a drought devastated land.

1

(Ngarrindjeri Country: Meeting of the waters. i This is where fresh and salt water meet at the Murray

Mouth. This includes the Goolwa Channel and the Currency and Finniss River and is protected under

South Australia's Aboriginal Heritage Act 1988 . Image: B MacGill).

Our Lands, Our Waters, Our People, All Living Things are connected. We implore people to respect our Ruwe (Country) as it was created in the Kal-dowinyeri (the Creation). We long for sparkling, clean waters, healthy land and people and all living things. We long for the Yarluwar-Ruwe (Sea Country) of our ancestors. Our vision is all people Caring, Sharing, Knowing and Respecting the lands, the waters and all living things.

(Ngarrindjeri Tendi, Ngarrindjeri Heritage Committee, and Ngarrindjeri Native Title Managment Committee).

Introduction

The vision outlined above by Ngarrindjeri Elder Uncle Tom Trevorrow is an invitation for people to care, share, know and respect the lands and waters. This is a nonexclusive ethic of care associated with belonging to a place. This paper is concerned with the contested forms of belonging expressed by Ngarrindjeri and by settlers in the places encompassing the lower Murray River, the Lakes and the Coorong in the South East of South

Australia (Hattam, Rigney and Hemming). Both Ngarrindjeri and settler Australians occupy

this space, each asserting their authority in terms of the “governance of the prior” (Povinelli).

In this way, each asserts an autochthonic position of belonging, each relying upon particular perspectives about the land and about the nature of the care it requires. These different perspectives and their political implications will be outlined in this paper.

Primarily, this paper focuses on an ethics of care that incorporates human and nonhuman actors that are shaped by relationality. Dependency as relationality analysed in ethics of care theory routinely investigates human relations (Held; Ruddick; Levinas). The political project of belonging through an ethic of care is concerned with how people relate to each other, rather than on defining boundaries of belonging (Yuval-Davis 45). Primarily, ethics of care as a political and moral theory is concerned with relationality that deconstructs liberalism’s thesis of the atomistic individual (Venn). This paper expands current ethics of care debates by including non-human actors (Latour), such as water systems, to explain how human actors’ dependence on ecological environments shapes their understanding of belonging.

The ailing Murray River in this region of South Australia is in crisis and depends on a network of actors to care for its return to health. The Murray River is the main water supply for South Australians. It has been depleted by commercial irrigation and altered by damming, weirs, locks and barrages so that it has ironically become a non-human life-giving force that is now dependent on human action for its own survival. This paper will focus on ethics of care as a “political project of belonging” (Yuval-Davis); it explores how the millennium drought has shaped settler Australian’s understanding of belonging, as well as how

2

Ngarrindjeri Ruwe/Ruwar has informed a land/water ethics of care in this drought devastated region.

An ethic of care as discussed in the first section of this paper is concerned with relations and therefore is associated with belonging, since belonging to a place means being embedded in a network of connections to people and locations. In postcolonial places, claims to belong are politically charged, especially when they are naturalised by colonisers or

settlers and framed in terms of autochthony (Rigney, Hemming and Berg). When settlers

claim autochthony they necessarily displace the authentic autochthony of Indigenous nations, in accordance with the notion of Terra Nullius. The middle section of this paper will outline the South Australian case study of environmental care for the River Murray highlighting a problematic settler perspective that mobilises Ngarrindjeri’s notion of Caring for Country to assert its own autochthonous belonging. In the final section of the paper it is argued that recognition and respect for the autochthony of the Ngarrindjeri nation and understanding of

Ngarrindjeri ethic of care as a non-exclusive mode of belonging can be accessed through

Ruwe/Ruwar, but importantly, this process involves recognition of Ngarrindjeri as First

Nations peoples as well as carrying out and investing in the responsibilities required to appropriately care for this Country.

The aim of this paper is to outline these political aspects of belonging and explore how concepts of care (and their related notions of connection to place) are mobilised with various agendas. Therefore, it is necessary to analyse the political operation of relational care, which can be used positively to build and renew relationships but can alternatively be used to justify colonial agendas of belonging. In this context, it will be argued that it is important for

Indigenous and settler communities to cultivate an ethic of caring for country that respects

Indigenous autochthony, while productively building the caring networks - human and nonhuman - that allow for a non-imperial belonging to the environment that sustains life.

Ngarrindjeri pedagogy instructs how this may be achieved; crucially, it requires settlers to cultivate forms of belonging that resist spurious notions of settler autochthony.

It will be argued throughout this paper that the decline of the health of the Murray

River has led to a major shift in understanding by settler society regarding land and water

care (Hemming, Rigney and Pearce). This provides an opportunity for the Ngarrindjeri nation

to mobilise political power as the traditional owners of the lower Murray River, Lakes and

Coorong in the South East of South Australia and the nurturers of the land and waters for millennia. Ethics of care provides the lens to examine these social and political intersections

(Yuval-Davis).

Ethics of care

Ethic of care is associated with the notion of belonging through relations, since belonging to a place means being embedded in a network of connections to people and locations. This section outlines ethic of care theory and its limitations regarding its anthropocentric focus that is insensitive to cultural, racial and class differences. However, the

South Australian case study of environmental care for the River Murray as a political and emotional project of belonging expands ethics of care theory by considering connections with non-human-agents. These connections shape capacities for belonging in important ways, allowing for the development of a postcolonial analysis of the relationship between care claims and the politics of belonging.

3

The concept of ethics of care is informed by feminist methodologies and has been framed and defined by a number of key theorists in response to a justice-based moral ethics

(Gilligan; Noddings; Held; Ruddick). Caring theory has largely been confined to the analysis of dependence and relationality, particularly in gendered, classed and raced models of care

(Bignall). However, these debates have largely been limited to human need and dependency represented by the mother/child relationship. The drive to raise care to a status commensurate with justice has reinvigorated the care/justice discourse where:

…an ethic of justice focuses on questions of fairness, equality, individual rights, abstract principles, and the consistent application of them. An ethic of care focuses on attentiveness, trust, responsiveness to need, narrative nuance, and cultivating caring relations. Whereas an ethic of justice seeks a fair solution between competing individual interests and rights, an ethic of care sees the interest of carers and cared-for as importantly intertwined rather than as simply competing. Whereas justice protects equality and freedom, care fosters social bonds and cooperation (Held 15).

Gilligan's work has been of particular significance in the care/justice debate as she challenges patriarchal values that position women and caring practices as secondary to justice. She asks why hegemonically constituted forms of justice are privileged over more feminised notions of caring and nurturing? In her influential book, In a Different Voice,

Gilligan (1982) argues that caring for others is equally important to justice, and her work is significant for its deconstruction of gendered research methods of inquiry (Bignall). Criticism of Gilligan’s theory is its tendency to universalise women’s experiences (Yuval-Davis 180) and its limitation in relation to its application to the law (Auerbach et al.; Drakopoulou).

These limitations extend also to ethics of care theory in its early inception, particularly in relation to the absence of critique of whiteness (Rolón-Dow; Thompson; MacGill) in relation to extended family models of care, land ethics of care or a species ethics of care (Rose).

The focus of the theory has largely been limited to the justice/care debate concerning humans; however, it does lends itself to the inclusion of ecology since the relationship of dependency between the human and non-human actors plays a critical role in understanding the responsibilities inherent in belonging. Plumwood argues: “the problem is not primarily about more knowledge or technology; it is about developing an environmental culture that values and fully acknowledges the non-human sphere and our dependency on it, and is able to make good decisions about how we live and impact on the non-human world” (3).

Significantly, as a result of the millennium drought an environmental culture has developed within the national response to address the Murray-Darling basin ecological crisis.

The Murray-Darling basin extends over one million square kilometres and includes the River

Murray, the Darling River, the Murrumbidgee River, the creeks and estuaries that flow into these systems, wetlands, as well as Coorong, Lower Lakes and Murray Mouth Ramsar site

(Commission). It is the very uncertainty of the state of the Murray River’s health that has urged Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities to re-assemble (Latour) new ways of addressing the continued salinity crises and extinction of species following the drought.

As a result, new modes of association have developed concerning the Murray River and the Murray Darling Basin. Community values have shifted as a result of the stress caused by the drought and salination of the Murray River. This stress has both divided and aligned various sectors of the community. Ever since the drought began, irrigators, farmers,

4

environmentalists and Ngarrindjeri leaders have gathered at major public events to pitch their position as stakeholders in the Murray River, to share knowledge and to explore new ways to work together (Marsden et al.).

The impact of the drought on the Murray River has been significant as it has led to new relationships “that did not exist before and that to some degree [modify] two elements or agents” (Latour) that were historically conceptualized along one binary trajectory, that is,

Indigenous (colonised) and non-Indigenous (coloniser). The fractured relations between environmentalists, and the farmers, irrigators and water front beach shackers also stood in binary positions until the drought brought forth the understanding that saline water was unusable and highly destructive to the fresh water environment.

Reluctantly or willingly, these heterogeneous stakeholders are involved in new networks that are being redesigned by each other’s stories. They have been shaped by their own experiences of deprivation, where the recognition of water as a life source is seen as a gift of nature rather than something that can be considered as a boundless possession.

Belonging in this case is the assemblage of locatedness that is molded by understandings of injured sites and peoples (Gruenewald) and performed through the enactment of care of the lands and waters. Belonging is an investment that involves one’s responsibility as a carer within webs of interactions and an ethic of care provides for the emotive and political aspects of belonging through fulfilling responsibility in dependent relationships, whether they are human or non-human actors.

The notion of Ruwe/Ruwar is a Ngarrindjeri ontology that can be expressed as an ethic of care and whilst it is much more than an ethic of care, the responsibility of caring for

Country remains central.

ii Ngarrindjeri Ruwe/Ruwar includes the ethical obligation to care for country as the land/waters are dependent actors because they rely for their viability on human beings to ensure their health and vice versa. The conceptual shift involves “belonging to the land” (Reynolds) rather than owning the land. “ Ruwe / Ruwar is a concept that encapsulates the interconnection of Ngarrindjeri people, their lands, waters and all living things. This includes the spirits of Ngarrindjeri ancestors” (Hemming, Rigney and Berg 93).

Tom Trevorrow, Chair of the Ngarrindjeri Heritage Committee states in the Ngarrindjeri

Nation Yarluwar-Ruwe Plan:

The land and waters is a living body. We the Ngarrindjeri people are a part of its existence. The land and waters must be healthy for the

Ngarrindjeri people to be healthy. We are hurting for our Country. The

Land is dying, the River is dying, the Kurangk (Coorong) is dying and the Murray Mouth is closing. What does the future hold for us?

(Ngarrindjeri Tendi, Ngarrindjeri Heritage Committee, and

Ngarrindjeri Native Title Managment Committee)

The physicality of belonging embodied through a land ethic of care is defined by Weir as “connectivity” (Weir). Entwined with belonging to the land in this way is the ethical obligation to be morally responsible for caring for country. In the same way ethics of care’s starting point is the relational subject between mother and child (See Held 2006, p. 13), so is

Ngarrindjeri relationality inherent in Ruwe/Ruwar. Shifting from an individualist perspective to a position of inter-relationship between the landscape and the human collective allows for an alternative moral philosophy and a caring perspective that includes a land/water ethic of care. This includes the responsibilities involved in caring for lands and waters as an expression of belonging. Arguably, it is only over time that human actors are shaped by the

5

lands and waters which provide the insight into how to care for the needs of the lands and waters. It is this Ngarrindjeri knowledge that has been developed over 40,000 years that is being used to respond the Murray River environmental crisis.

The concept of Ruwe/Ruwar is infiltrating Natural Resource Management plans, which signifies an intervention into the colonial archives. The urgency of the environmental crisis concerning the Murray River and surrounding lands calls into play a need for settlers and First Nations people to create a healthy country (Ngarrindjeri Tendi, Ngarrindjeri

Heritage Committee, and Ngarrindjeri Native Title Managment Committee). The

Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority (NRA-peak body of the Ngarrindjeri nation) remain committed to the principles of Ruwe/Ruwar in negotiations which express the connection between material, spiritual, human and non-human actors.

This notion of connectedness is shared in a reconciliatory manner by Ngarrindjeri

Elders who consistently extend opportunities for settler Australians to understand

Ruwe/Ruwar. Connection to Country and the enactment of belonging can be understood, for example, through the practice of weaving. Weaving has deep cultural and metaphorical significance and as Ngarrindjeri Elder Aunty Ellen Trevorrow notes it also involves learning from stories:

There is a whole ritual in weaving, from where we actually start the centre part of the piece, you’re creating loops to weave into, then you move into the circle. You keep going round and round creating the loops and once the children do those stages they’re talking, actually having a conversation, just like our Old People. It’s sharing time. And that’s where our stories are told (Bell 44).

Bell states the “weaving metaphor also acknowledges that strength resides in the interweaving of materials, that new items can be incorporated and interpreted within the stories told by the old people” (Bell 594). The image below is part of an art work by

Ngarrindjeri weavers on Hindmarsh Island as an act of resistance against the “fabrication” allegation in the Hindmarsh Island Bridge Royal Commission which will be outlined in the next section. The mat is a signifier of resistance and an example of how stories are re-weaved into objects.

(Woven mat on Gate: Hindmarsh Island. Photo: B MacGill)

As in weaving, new items can be incorporated into stories including new ways to negotiate with settler Australia. However, danger of erasure through the silencing of

Ngarrindjeri voice as First Nation citizens is an ongoing colonial practice particularly when

6

“alternative systems of signification” disrupt “patriarchal assumptions underlying dominant representations of belonging and land use” (Bignall). These assumptions embedded in the principles of British sovereignty and challenged by Ngarrindjeri law and spirituality are part of political systems of belonging that will be analysed in the next section in relation to autochthony.

Autochthony (to be of the soil)

In postcolonial places, assertions to belong through autochthony are political as authentic autochthony of Indigenous nations are negated when settlers represent their autochthony as naturalised in accordance with the legal doctrine of Terra Nullius. This political aspect of belonging means that concepts of care and their related notions of connection to place are mobilised within asymmetrical power relations. Therefore, it is necessary to analyse the political operation of relational care, which can be used positively to build and renew relationships but can alternatively be used negatively to justify colonial agendas of belonging.

The Greek word “autochthony” (to be of the soil) (Yuval-Davis 99) is used as a signifier of social belonging and setter Australians routinely make a priori claims to belonging through the time they have been part of this land, and through things such as having one’s grandparents buried in the land. Ngarrindjeri autochthonic claims include first fire stories, creation stories and 40,000 year old ancestral remains (Bowler et al 2003). Settler narratives tend towards boundary marking and assume a “‘naturalised” position These coexistent and competing claims demonstrate how “autochthonic politics of belonging can take very different forms in different countries and can also be reconfigured constantly in the same places. Nevertheless, like any other forms of racialisation and other boundary constructions, their discourses always appear to express self-evident or even ‘natural’ emotions and desires”

(Yuval-Davis 101).

The politics of belonging within the Australian constitution and bordered by the doctrine of Terra Nullius highlight the “multi-dimensional legacy of Europe’s colonial encounters in Australia’ and its ‘embedded structural racism” (Howitt) expressed through the failure under International law to recognise Indigenous autochthony. These founding racialised legal flaws constitute the discourse of colonial belonging in Australia. The

“substantive problems inherent in the body of the constitution brought about by the framers’ desire to enable Australia’s parliament to discriminate on the base of race” remains alive and well in this country. The “races power” outlined in section 51(26) of the constitution allows the “Commonwealth to pass laws that discriminate on the basis of … race” 152 (Williams).

So when Ngarrindjeri autochthonic claims were brought to public attention in the mid-1990s during the Hindmarsh Island Case, Australian legal and political boundaries of belonging became clearly demarcated (Bell) and Australian Indigenous rights to belong were again denied.

Ngarrindjeri’s resistance to colonisation (Tendi 2003, 68) and Ngarrindjeri sovereignty were expunged under western law in this infamous Hindmarsh Island Bridge

Royal Commission (Bell) that concluded that Ngarrindjeri women’s sacred business was a fabrication. In this case Ngarrindjeri perspectives were silenced by settler law, even though the Mabo v Queensland (No2) (1992) 175CLRI case recognised Native Title and thereby

Indigenous law and spirituality. Ngarrindjeri autochthony was displaced by the doctrine of

7

Terra Nullius (‘land belonging to no one’) in 1995 despite the Mabo judgment of 1992 that repealed the notion of terra nullius and the Native Title Act 1993 that recognised Indigenous sovereignty. Settler claims to autochthony are made through Common law. The autochthonic law from British sovereignty does not, but under International law should, take into account pre-existing Ngarrindjeri law.

iii

Like most colonised countries, settler narratives, politics and law have been framed through an “argumentative” approach (Yuval-Davis 91) within asymmetrical power relations.

In more recent times, the State and the leaders of the Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority

(NRA) have come to the negotiation table with different sets of values and both positions emerge from the “governance of the prior” (Povinelli). One is an artificially transplanted set of values and laws and the other emerges from sets of values and laws that are grounded in a land ethic. Povenelli states:

If in creole nationalism the preeminent question is how a settler can claim the right to own and govern the land, then the answer isn’t found in the governance of the prior per se , but in how the prior is split across two narrative formations of truth-value: the tense of the settler and the tense of the indigenous. The truth-value of the indigenous-aboriginal-native (genealogical) voice is figured in the past perfect, while the truth value of the settler (autological) is figured in the unmarked present or future anterior. This division of the tense of the nation bifurcates the sources and grounds of social belonging in such a way that the mutually implicated (the settler colonial and indigenous as dialectical characters) are transformed into differentially valued and assessed past and future truth-values

(Povinelli 23).

These contested ideas emerge through the struggle and discomfort of those settler societies in colonised lands that continue to tussle over in the hopefulness of connection.

Truth-values are measured on their falsity or veracity as statements of fact, and in this case, the settlers’ claim of belonging is granted greater value through the quantity of nationhood narratives that inform the public imaginary (Anderson).

Interestingly, the term “custodial responsibility” has recently been incorporated into the vernacular by settler societies along the Murray River. This represents a significant linguistic shift in settler communities’ imaginary, that encompasses an understanding of responsibility towards caring for the lands and waters that sustain communities. However, dangers lie in the use of such terminology as it can simultaneously infuse the mindset required to appropriately engage with land/water practices, and yet at the same time, usurp

Indigenous autochthonic claims to land/water. The current Fight for the Murray is a case in point. The campaign focuses on settler narratives of belonging which are represented through a variety of media and online forums. The public sees and reads, via online documentaries and via television advertisements, stories by farmers, irrigators and wine makers who make desperate calls to save the Murray River. The online and media campaigns are designed to mobilise public action and receive signatures for support for this campaign. The fight over water allocation for South Australians highlights a significant shift in the narrative tense of these settler stories.

Povinelli reminds us of the dangers of privileging an origin of belonging position when the “geontological” spiritual connection to Country operates as the negotiating

8

framework for recognition and rights. “[O]rigin stories are interpreted as origin-myths, and these origin-myths are used in liberal politics of cultural recognition to differentiate the practices of the present from the practices of the past” (Povinelli 22). Whilst it remains significant to engage in differing paradigms of belonging it is dangerous to imagine only that which had belonged before as the entry point into negotiations with a system, such as the

Australian State, around rights. (For further discussions and detail on the specifics of

Ngarrindjeri negotiating practices refer to Hemming, Rigney and Berg 2010). However, at the same time, origin stories in combination with the use of autochthonic nomenclature have positively influenced current land/water policy.

The narrators and story tellers that represent the Save the Murray campaign refer to their rightful belonging through a custodial dialogue which highlights a problematic settler perspective. They locate themselves as the nation’s people of the area. Their narratives include their responsibility for the wellbeing of the area. They call upon South Australian citizens to help them defend their rights to belong as the caretakers and custodians of this water system (fightforthemurray.com.au/our-stories). Questions remain: Is this a dangerous slippage of tense, or does it signify a values shift towards an Indigenous epistemology? Does the environment remain constituted as a problem that these “custodians” can fix, such that land and water remain inert? Or is there a move to declare custodianship of land and water that are understood as actors that have agency in a similar way in which Ngarrindjeri position land and water within Ruwe/Ruwar ethics of care? Evidence of this shift occurred in 2012 when the water minister Tony Burke stated in his Press Club speech on November 22:

The game changer came in 1991. It should have been 1981 when the mouth of the Murray closed for the first time but that once again only impacted on one state. But it was in 1991 when the game changer arrived and a new player turned up to the negotiating table. In 1991 the new player arrived with a blue-green algae outbreak that went for one thousand kilometres and the environment turned up to the negotiating table and proved to be more ruthless and less compromising than any of the states. The environment turned up to the negotiating table in 1991 and said, if you're going to manage the river this way then none of you can have the water. Effectively, the rivers decided collectively that if we were going to manage the water as though it stopped at state boundaries then the water was willing to stop (“Water Matters”).

This highlights a significant ontological shift regarding land/water care by the State.

The new networks and narratives also allow for Ngarrindjeri agency to assert a sovereign responsibility to care for country in public locations as the Traditional Owners, but they do not necessarily shift the broader settler notion of entitlement which is “an enduring product of white settler, colonial history” (Ang). Hage also outlines a notion of “governmental belonging” that is privileged within settler society and states that:

…[i]t is clear this governmental belonging … is claimed by those who are in a dominant position. To inhabit the nation in this way is to inhabit what is often referred to as the national will . It is to perceive oneself as the enactor or agent of this will. … It is also by inhabiting this will that the imaginary body of the nationalist assumes its gigantic size, for the latter is the size of omnipresence,

9

the size of those whose gaze has to be constantly policing and governing the nation (Hage 46).

However, there has been a crisis in national will that has disrupted settler society’s understanding of belonging through entitlement. The water crisis of the Murray River has led to reconsiderations of sustainable living practices and involves new ways to conceptualise caring for the environment including embedding Ngarrindjeri knowledge systems to help manage the environmental crises. Indeed, “Indigenous knowledge is increasingly accepted as a valid and necessary information input to biodiversity management” (Committee). The shift is represented by an intention to manage the river sustainably, which embodies caring for country as an enactment of responsibility.

The drought significantly impacted on the psyche of South Australians and as a result there has been both macro and micro political shifts towards caring for lands and water in this region. Moreover, on a Federal level, the drought has been the impetus of policy changes and funding arrangements that include the Caring for Country program. This marks important steps towards a plurality that is not reduced to an autochthonic politic of belonging. Whilst

Jackson et al (2009) point to the failure of the State to recognise Indigenous peoples’ values and interests within water planning, there have been recent movements within departments concerning water and land management that engage Indigenous land ethics of care, in particular land and sea management plans (Commission) iv

and since 2004 the “National

Water Initiative (NWI) requires jurisdictions to provide for Indigenous access to water resources through planning processes and inclusion of Indigenous customary, social and spiritual objectives in water plans” (Jackson, Tan and Altman 1). Critical to the inclusion of

Indigenous perspectives in water plans are appropriate research practices where Indigenous voices are heard without distortion.

KNYs: ‘Kungan Ngarrindjeri Yunnan’ or ‘Listen to Ngarrindjeri people talking’

The political shifts outlined above highlight how belonging is a politically contested constellation that includes relational care with non-human actors assembled in various formations. The process of re-belonging inspired by the water crisis has opened opportunities for Ngarrindjeri agency to assert sovereign responsibility within the borders of the nation.

However, as outlined in this section it is critical for settler communities to cultivate an ethic of caring for country that respects Indigenous autochthony. This attitude of respectfulness necessarily involves settler communities being willing to engage in Kungan Ngarrindjeri

Yunnan (Listen to Ngarrindjeri people talking). Arguably, settler calls for a land/water ethic of care is moving towards Ruwe/Ruwar, but it remains critical that the governing authority of the Ngarrindjeri nation can be heard. Such an enactment of respectful relationality through hearing acknowledges the authority of the Ngarrindjeri nation to invite all to share in caring for country as defined by Elder Uncle Tom Trevorrow at the beginning of this paper.

Ngarrindjeri ethic of care is non-exclusive and invites all to share in caring for

Country; but at the same time calls for acknowledgement of, and respect for, the autochthony of the Ngarrindjeri nation (which then is invested with the authority to issue the invitation to share and care). The inside/outside status of the Ngarrindjeri nation facilitates what Deloria calls “pivoting the power structures” in order to further mobilise agency (in Bruyneel 146).

10

This includes the political project of overturning past colonial practices of Ngarrindjeri erasure (See Hemming et al.) and involves nation building activities that have been created through negotiated contractual agreements called KNYs: Kungan Ngarrindjeri Yunnan or

“Listen to Ngarrindjeri people talking”. KNY Agreements are contracts that provide a strategic process for political negotiations. KNYs can vary from negotiated arrangements with a local council regarding Ngarrindjeri Heritage issues to State wide agreements.

Hemming and Rigney state:

In 2009 the Ngarrindjeri nation in South Australia negotiated a new agreement with the State of South Australia that recognised traditional ownership of Ngarrindjeri lands and waters and established a process for negotiating and supporting Ngarrindjeri rights and responsibilities for country (Ruwe)…In line with Ngarrindjeri political and legal strategies, it takes the form of a whole-of-government, contract agreement between the Ngarrindjeri nation and the state of South Australia. Called a

“

Kungan Ngarrindjeri Yunnan” or “Listen to what Ngarrindjeri people have to say”, it provides for a resourced, formal structure for meetings and negotiations between the Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority (NRA:

Peak body) and government, university and other non-Indigenous organisations (Hemming and Rigney).

The Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority is directly negotiating with State and Federal governments about natural resource management in order to ensure that Ngarrindjeri peoples’ ethical obligations are enacted within legislation and policy to care for country (Hemming and Rigney). Moreover, Ngarrindjeri knowledge about the long term sustainable management of the Murray River system has increasingly become useful to the State regarding how to manage the environmental crises. Ngarrindjeri people have entered a new era of recognition that facilitates an exercise of agency and authority within the nation state.

The Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority moved into a new phase of micro-political work that required new forms of political literacies that are mobilised in each new assemblage that shifts macro-political systems (Hemming and Rigney 2008). Arguably, this political work has re-shaped alternative versions of belonging. However, these new associations have been formed through not only contractual relationships, but also through good will and relationship building (Resources and Authority). Re-forming social relations requires an ethic of care where the spirit of negotiation plays into the long term process of care and concern for not just the environment, but also for the human actors involved in the negotiating process. This does not ignore the hard contractual work and challenges with negotiations; however it is the combination of various actors and processes that create the new assemblage (Bennett and

Healy; Latour).

The leaders of the Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority negotiate with leaders of the State regarding natural resource management, and economic and social issues concerning

Ngarrindjeri. The “Leader to Leader” meetings between the State and the Ngarrindjeri

Regional Authority leaders, signifies a shift towards a shared aim of caring for country through negotiation that has been affirmed in policy.

Importantly, the Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority that was formed in 2007 as the peak body of the Ngarrindjeri nation developed its policies within its own management plan called the

Ngarrindjeri Nation Yarluwar-Ruwe Plan (Caring for Ngarrindjeri Sea, Country and

11

Culture). This is a key text that reflects Ngarrindjeri visions and goals as outlined in the quote at the beginging of this paper.

This vision statement and set of goals marks a new kind of engagement between the Ngarrindjeri nation, the State, and other non Indigenous interests (see Smyth 2007). Ngarrindjeri leaders are attempting to interrupt the ongoing cycle of colonialism that governs their lives, and the lives of their communities, by formalizing their aspirations and identity as a First Nation in the form of a high-profile management plan.

They hope that this plan will act as a form of treaty, setting a baseline for all future plans impacting on Ngarrindjeri Yarluwar-Ruwe. The

Yarluwar- Ruwe Plan forms a critical part of the new regional

Ngarrindjeri response to colonization in southern South Australia, a space where treaties should have been negotiated but were not

(Hemming and Rigney).

The application of contracts, as well as policy texts such as Ngarrindjeri Nation

Yarluwar-Ruwe Plan , compacts with the State, and Statements of Commitment with the State are strategic enactments to political belonging. Belonging in this sense is assembled through negotiating with the State whilst at the same time centralising Ngarrindjeri sovereignty.

Ruwe/Ruwar ethic of care grounds these negotiations as it is the right to care for country in specific ways which informs responsibilities as sovereign agents.

An ethics of care model incorporates the practices of care, in terms of physicality, and also operates as a moral philosophy. In this context, care is informed by its traditional meaning as a verb: “to look after”, as well as its use as a noun; something requiring attention and responsibility. In this sense, it allows for greater scope to understand the complexities of belonging as a physical and an emotional process, as well as a sovereign responsibility. The political project of belonging includes the necessary requirements of recognition and rights which has been achieved through Ngarrindjeri political agency that is enacted through KNY

Agreements/contracts.

This political assemblage of belonging is part of the constellation which Carter highlights in his alternative assemblage of belonging “where the greatest differences can be expressed simultaneously and, instead of cancelling each other out, be instantaneously transferred from one side to the other” (Carter). Carter’s work on belonging includes the need to name where one fits as part of the process of assembling ways to belong. He poignantly states:

In affiliating to others’ country, it seems essential to declare where one comes from-even if-, in the rhetoric of nation building; the past life of migrants must be annulled. The implication of this declaration is that creativity exercised at this place will stage a conversation with those who have departed; just as the outside artist is, from the perspective of the environment whence they came, classified as departed and ghostlike. There emerges from this dialectic the recognition of the doubled or multiple identities of selves and places.

To endow this ambiguity with epistemological significance, to appreciate it as a technique for letting back into the design of the future a complex emotional domain whose elements always come from somewhere else (even when that somewhere else is here) seems

12

to me to give a better account of historical, environmental and spiritual realities in a global context. Because of this, it suggests new ways of thinking the boundaries of places and the communities who produce and enjoy them (Carter 21).

A land/water ethic of care, where one belongs to the land offers a “mode of ownership and sovereignty in which more than one ethnic/national collectively can co-exist” (Yuval-

Davis 105). The Ngarrindjeri Regional Authority’s principle of Ruwe/Ruwar is not focused on boundary marking, but instead, it offers an invitation for all citizens to take responsibility for the care of water and land as a living body.

As a result of the drought and the salinity crises of the Murray River since the 1990s, settler society has shifted towards a plural understanding of belonging that is shaped by an

Indigenous notion of Caring for Country in a fragile land. Prior to this, the period 1880 –

1890 saw a major drought across the whole country that plunged the economy, which was built on agriculture, into recession. However, this is a limited experience compared to

Ngarrindjeri occupation on these lands and waters over 40,000 thousand years. Belonging and understanding how to belong as relational and dependent subjects with the land and waters is shaped by time, experience and the stories that are passed down intergenerationally. It takes time for the rhythm of the lands and waters to be embodied and whilst this does not define belonging it does shape the way in which we learn to understand how to care for the land and waters as an enactment of belonging.

It is important for Indigenous and settler communities to cultivate an ethic of caring for country that respects Indigenous autochthony, while productively building the caring networks - human and non-human - that allow for a non-imperial belonging to the environment that sustains life. Ngarrindjeri pedagogy instructs how this may be achieved; crucially, it requires settlers to cultivate forms of belonging that resist spurious notions of settler autochthony.

Conclusion

When actors are informed by an ethics of care that includes Caring for Country, the question of belonging shifts from who belongs to how one belongs. Ethics of care as a political project of belonging is an “alternative metaphysic” that allows for a land/water ethic of care, where non-atomistic features, such as cultural landscapes, rivers and mountains, as well as all sentient creatures are agents of a symbiotic system. The Murray River as a nonhuman agent has changed the ways of belonging in a harsh country towards an ethics of care of belonging that is both political and moral.

Understanding ethical obligations to Country as an enactment of belonging includes as Graham calls “a habitus of woven stories, a discursive locus where belonging is figuratively defined and renewed” (qtd. in Carter 30). Through drawing out the conditions of belonging it is possible for settler Australians to assemble place making through acknowledgement of their ancestral heritage and thereby as Carter argues provide the “critical precondition of gaining lawful access to country here” (Carter 30).

The political and social shift in belonging is signified by changes in policy and environmental management plans, including the Caring for Country program, KNY agreements, the agency of Ngarrindjeri people to care as paid employees for the lands and waters in the Lower Lakes, Coorong and Murray River rightfully and legally, as well as the shift in settler narratives of belonging. Whilst the Federal Government instructed the Murray-

13

Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) to deliver a plan to restore the river to health, this process has included shifting ontologies towards understanding the entire River system as a body underpinned by the notion of “connectivity” (Weir). The political project of belonging through the lens of an ethic of care allows for the vision of relationship building and shared knowledge that have led to this plural understanding of ‘connectivity’ (Weir).

As outlined throughout this paper, an ethic of care involves relationships and therefore is allied with 'belonging', as belonging to a place means being rooted in a network of associations to people and locations. However, when entitlements defined through settler’s naturalised autochthonic claims are made it is politically problematic in postcolonial sites, as it displaces the authentic autochthony of Indigenous nations as in the case of the Hindmarsh

Island Bridge Royal Commission that reported in accordance with the notion of Terra

Nullius. This exercise in belonging has been contested and used to highlight the political operation of relational care, which can be used positively to build and renew relationships but can alternatively be used negatively to justify colonial agendas of belonging.

The Murray River case study of environmental care has significantly shaped new conceptualisations of belonging. Significantly, this move towards a Ngarrindjeri ethic of care is non-exclusive and is not based on entitlement. Instead, it is an invitation for all to share in caring for Country; but at the same time appeals for acknowledgement of, and respect for, the autochthony of the Ngarrindjeri nation which grants the authority to issue the invitation to share and care. It is critical for Indigenous and settler communities to cultivate an ethic of caring for country that respects Indigenous autochthony, and at the same time creates positive caring networks for both human and non-human actors that allow for a non-imperial belonging to the environment that sustains life. To lawfully belong and access a rightful place emerges from how we care for the place in which we live and how well we listen to the ways in which it calls us into belonging.

v

References (Works Cited)

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of

Nationalism . Verso, 2006. Print.

Ang, Ien., ed. Asians in Australia: A Contradiction in Terms?

Sydney: UNSW Press, 2000.

Print.

Auerbach, Judy, Linda Blum, Vicki Smith and Christine Williams.

"Commentary on

Gilligan's 'In a Different Voice'." Feminist Studies 11 (1985): 149-62. Print.

Bell, Diane. Ngarrindjeri Wurruwarrin: A World That Is, Was and Will Be . Melbourne:

Spinifex, 1998. Print.

Bennett, Tony and Chris Healy. "Introduction: Assembling Culture." Assembling Culture .

Eds. Bennett, Tony and Chris Healy. New York: Routledge, 2011. 1-45. Print.

Bignall, Simone, 'Affective Assemblages: Ethics Beyond Enjoyment.” Eds. Bignall, Simone and Paul Patton. Deleuze and the Postcolonial , edn. First, Edinburg: Edinburgh

University Press, 2010. 78 – 103. Print.

Bowler, James, Johnston, Harvey, Olley, Jon, Prescott, John, Roberts, Richard, Shawcross,

Wilfred and Spooner, Nigel."New Ages for Human Occupation and Climatic Change at Lake

Mungo, Australia." Nature 421.6925 (2003): 837-40. Print.

14

Carter, P. Living in a New Country: History, Travelling, Writing . London: Faber and Faber,

1992. Print.

Carter, Paul. "Care at a Distance: Affiliations to Country in a Global Context." Landscapes and Learning. Place Studies for a Global Village . Eds. Somerville, Margaret, K

Power and Paul de Carteret. Rotterdam: Sense, 2009. 21-33. Print.

Commission, Australian Human Rights. "Native Title Report. Case Study 2. The Murray-

Darling Basin–an Ecological and Human Tragedy." ACT: Australian Human Rights

Commission, 2008. 265-99. Print.

Committee, ASEC Australian State of the Environment. "Australian State of the Environment

2006 Independent Report to the Commonwealth Minister for the Environment and

Heritage." Ed. Heritage, Department of the Environment and. Canberra: CSIRO

Publishing on behalf of the Department of the Environment and Heritage, 2006 Print.

Drakopoulou, Maria. "The Ethic of Care, Female Subjectivity and Feminist Legal

Scholarship." Feminist Legal Studies 8.2 (2000): 199-226. Print.

Gilligan, Carol. In a Different Voice . Cambridge: Havard University Press, 1982. Print.

Gruenewald, David. "The Best of Both Worlds: A Critical Pedagogy of Place." Educational

Researcher 32.4 (2003): 3-12. Print.

Hage, Ghassan.

White Nation. Fantasies of White Supremacy in a Multicultural Society . New

South Wales: Pluto Press, 1998. Print.

Hattam, Robert , Daryle Rigney, and Steve Hemming. "Reconcilation? Culture, Nature and the Murray River." Fresh Water: New Perspectives on Water in Australia . Eds.

Potter, E, et al. Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2007. 105-22. Print.

Held, Virginia The Ethics of Care. Personal, Political, and Global . Oxford Oxford

University Press 2006. Print.

Hemming, Steve, Daryle Rigney and Sean Berg. "Researching on Ngarrindjeri Ruwe/Ruwar :

Methodologies for Postive Transformation." Australian Aboriginal Studies 2 (2010):

92-106. Print.

Hemming, Steve and Daryle Rigney. "Unsettling Sustainability: Ngarrindjeri Political

Literacies, Strategies of Engagement and Transformation." Continuum: Journal of

Media & Cultural Studies 22.6 (2008): 757-75. Print.

Hemming, Steve, and Daryle Rigney. "Unsettling Sustainability: Ngarrindjeri Political

Literacies, Strategies of Engagement and Transformation." Continuum: Journal of

Media & Cultural Studies 22.6 (2008): 757-75. Print.

Hemming, Steve, Daryle Rigney, and Meryle Pearce. "Justice, Culture and Economy for the

Ngarrindjeri Nation." Fresh Water: New Perspectives on Water in Australia . Eds.

Potter, E, et al. Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2007. 217-33. Print.

Hemming, Steve and Daryle Rigney. "Ngarrindjeri Ruwe/Ruwar: Well-Being through Caring for Country." Mental Health and Well Being. Educational Perspectives . Eds. Rosalyn

Shute et al. Adelaide: Shannon Research Press, 2011. 351-56. Print.

Hemming, Steve, et al. "Caring for Ngarrindjeri Country: Collaborative Research,

Community Development and Social Justice." Indigenous Law Bulletin 6.27 (2007):

6-8. Print.

Howitt, Richie. "Frontiers, Borders, Edges: Liminal Challenges to the Hegemony of

Exclusion." Australian Geographical Studies 39.2 (2001): 233-45. Print.

Jackson, Sue, Poh Ling Tan, and Jon Altman. "Indigenous Fresh Water Planning Forum:

Proceedings, Outcomes and Recommendations." Canberra: National Water

Commission, 2009 Print.

15

Kungun Ngarrindjeri Yunnan Agreement Regulators.Eds. Tendi, Ngarrindjeri, et al., 2009.

Print.

Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory . Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 2005. Print.

Latour, Bruno. "On Technical Mediation " Common Knowledge 3.2 (1994 ): 29-64. Print.

Levinas, Emmanuel. Alterity and Transcendence . London: Athlone Press, 1999. Print.

MacGill, Bindi. "Aboriginal Education Workers: Towards Equality of Recognition of

Indigenous Ethics of Care Practices in South Australian Schools." Flinders 2008.

Print.

Marsden, Susan, et al. "The Murray-Darling Basin Plan: From the Past into the Future." The

Murray-Darling Basin Plan: from the past into the future . Ed. Print.

Murray Darling Basin Authority. Water Matters 24. November 22, 2012, Web 2 Feb. 2013.

Ngarrindjeri Tendi, Ngarrindjeri Heritage Committee, and Ngarrindjeri Native Title

Managment Committee. Ngarrindjeri Nation Yarluwar-Ruwe Plan: Caring for

Ngarrindjeri Sea Country and Culture . Meningie, South Australia: Ngarrindjeri Land and Progress Association, 2006. Print.

Noddings, Nel. Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education . Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1984. Print.

Plumwood, Val. Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason . Routledge, 2002.

Print.

Povinelli, Elizabeth. "The Governance of the Prior " Interventions 13.1 (2011): 13-30. Print.

Read, Peter. Belonging. Australians, Place and Aboriginal Ownership . Cambridge

Cambridge University Press, 2000. Print.

Resources, Department of Environment Water and Natural, and Ngarrindjeri Regional

Authority. "Knya Taskforce Report 2010-11." Ed. DENR. Adelaide, 2010-11. Print.

Reynolds, Henry. Aboriginal Sovereignty: Reflections on Race, State and Nation . St

Leonards: Allen & Unwin, 1996. Print.

Rigney, Daryle, Steve Hemming, and Shaun Berg. "Letters Patent, Native Title and the

Crown in South Australia." Indigenous Australians and the Law.

Eds. Hinton, M.,

Daryle Rigney and E Johnston. 2 ed. Sydney: Routledge-Cavendish, 2008. 161-78.

Print.

Rolón-Dow, Rosalyn. "Critical Care: A Color(Full) Analysis of Care Narratives in the

Schooling Experiences of Puerto Rican Girls." American Educational Research

Journal 42.1 (2005): 77-111. Print.

Rose, Deborah-Bird. "Decolonising the Discourse of Environmental Knowledge in Settler

Societies." Culture and Waste: The Creation and Destruction of Value . Eds. Hawkins,

G. and Stephen Muecke. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003. Print.

Ruddick, Sara. Maternal Thinking: Towards a Politics of Peace . London: The Women's

Press, 1983. Print.

Tendi, Ngarrindjeri, Ngarrindjeri Native Title Management Committee and Ngarrindjeri

Heritage Committee. Ngarrindjeri Petition on Indigenous Rights to Governor of South

Australia , Meningie, South Australia: Ngarrindjeri Land and Progress Association, 2003.

Print.

Tendi, Ngarrindjeri. Ngarrindjeri Nation Yarluwar-Ruwe Plan: Caring for Ngarrindjeri Sea

Country and Culture . Meningie, South Australia: Ngarrindjeri Land and Progress

Association, 2006. Print.

Thompson, Audrey. "Not the Color Purple: Black Feminist Lessons for Educational Caring."

Harvard Educational Review 68.4 (1998): 522-55. Print.

16

Trevorrow, T., et al. They Took Our Land and Then Our Children: Ngarrindjeri Struggle for

Truth and Justice . Meningie, South Australia: Ngarrindjeri Lands and Progress

Association, 2007. Print.

Venn, Couze. "Individuation, Relationality, Affect: Rethinking the Human in Relation to the

Living." Body & Society 16.1 (2010): 129-61. Print.

Weir, Jessica. "Connectivity." Australian Humanities Review. Ecological Humanities .45

(2008): 153-64. Print.

Williams, George. "Removing Racism from Australia's Constitutional DNA." Australian Law

Journal 37.3 (2012): 151-55. Print.

Yuval-Davis, Nira. The Politics of Belonging. Intersectional Contestations . London Sage

2011. Print. i

The Meeting of the Waters is a fundamental aspect of the Ngarrindjeri world where all things are connected, whether they are living, from the past and/or for future generations. The Meeting of the Waters makes manifest core concepts of Ngarrindjeri culture that bind land, body, spirit, and story in an integrated, interfunctional world. The principles that flow from this cultural system are based upon respect for story, country, the old people, elders and family. The pursuit of these principles is contingent upon maintaining a relationship with country Kungun Ngarrindjeri Yunnan Agreement Regulators. The violation of these respect principles are manifest through the destruction of Ngarrindjeri yarluwar ruwe (a concept that embodies the connectedness and interfunctionality of their culture) and their effect upon the behaviours and survival of ngatji (the animals, birds and fish). According to these principles and contingent beliefs “environment” cannot be compartmentalised: the land is Ngarrindjeri and Ngarrindjeri are the land. All things are connected and interconnected. Ngarrindjeri philosophy is based on maintaining the integrity of the relationship between place and person. It is the responsibility of the living to maintain this continuity. The past is not and cannot be separated from the here and now or the future. To break connections between person and place is to violate Ngarrindjeri culture. The objective in undertaking activities upon Ngarrindjeri country should to not cause violence to Ngarrindjeri culture. (Kungun Ngarrindjeri Yunnan Agreement Regulators). ii Country, in this context means the lands and waters from which a person’s ancestors and Dreamings come and with which kin affiliations and identity are associated.

iii

Under International law the three “effective ways of acquiring sovereignty [are] conquest, cession, and occupation of territory that was terra nullius” (Mabo v Queensland (No2) (1992) 175CLRI, at 31 per Brennan J).

Given that Australia was conquered, it should have legally adopted the laws of Indigenous people until the State passed a law in parliament to overturn Indigenous law. The point I want to make is that Indigenous law existed.

Moreover, the Mabo decision recognised Indigenous autochthonic rights (including law and spirituality) which should have been granted forthwith the 1992 Mabo decision, yet Ngarrindjeri law and spirituality were not considered constitutionally valid in the 1995 Hindmarsh Island Bridge Royal Commission Report. iv

Please see: Coorong, and Lakes Alexandrina and Albert Ramsar Management Plan, 2000; National Oceans

Office published Assessment Report “Sea Country-an Indigenous Perspective”, 2002; ARCWIS, 2002, The

Living Murray Environmental Flows Project: A review of selected community engagement meetings in South

Australia, Victoria, and New South Wales, August-September, 2002, prepared for the Murray-Darling Basin

Commission; National Water Initiative, 2004; Draft Zoning for the Encounter Marine Park: Draft Zoning Plan

2005; South Australian Murray Darling Basin Integrated NRM Plan Investment strategy Phase 2, for 2004/5 to

2006/7; The Living Murray Program, 2009; Lower Lakes, Coorong and Murray Mouth Icon Site Environmental

Water Management Plan, 2012.

17

v

This paper was produced as part of the Australian Research Council Discovery Project, “Negotiating a Space in the Nation:

The Case of Ngarrindjeri” (DP1094869). The Chief Investigators are Robert Hattam, Peter Bishop, Pal Ahluwalia, Julie

Matthews, Daryle Rigney, Steve Hemming and Robin Boast, working with Simone Bignall and Bindi MacGill. I would like to formally thank Simone Bignall for her critical input, and support in the re-structuring and editing of this paper and Daryle

Rigney and Sue Anderson for their editorial support.

18