2011 MIT 150 Symposium Keynote Speech

advertisement

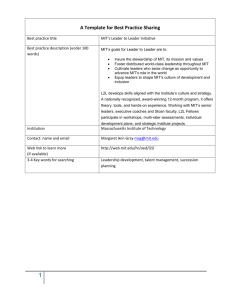

Nancy Hopkins Keynote for MIT150 Symposium Leaders in Science and Engineering: The Women of MIT March 28, 2011 1 If you’ve read a newspaper or a magazine in the last thirty years, you’ve undoubtedly read about the under-representation of women in Science and Engineering in the US, particularly at the high end of these professions. And no doubt you’ve heard of the infamous “leaky pipeline”, which refers to the fact that talented women in Science and Engineering have traditionally left these fields at a higher rate than men at every stage of the career, so by the time you get to the top the percent of women is very small. Enormous amounts of time, energy and money have been spent analyzing this problem. So, today we know a LOT about it. Perhaps not surprisingly, MIT has made several significant contributions to understanding the leaky pipeline: what causes it, and how to fix it. It turns out that understanding this problem requires two things: Analysis of the numbers of women in Science and Engineering as a function of time and what changed those numbers; and examination of the experiences of women who first entered these fields as undergraduates, became graduate students, joined university faculties and became full Professors. When you do these two things, the mystery begins to evaporate. And quite a fascinating story emerges. Today I’m going to take you through that story using primarily MIT data and experiences. But what I have to say applies to all comparable research universities. And much of what I have to say about the leaky pipeline of women in Science and Engineering pertains to the advancement of women to the top in other previously male-dominated occupations. It might surprise you to know that the % of women on the Science faculty of MIT today is greater than the % of women in the US Senate! NUMERICAL DATA: THE LEAKY PIPELINE I’ll begin with numbers that display the leaky pipeline. I’ll use data from MIT throughout because if there is one thing MIT excels at its collecting data. All the numerical data I will show is thanks to Lydia Snover and her wonderful colleagues in the Office of Institutional Research at MIT. Figure 1 shows the percent of MIT undergrads, graduate students, and faculty in Science and Engineering who are women. Today, about 45% of undergraduates majoring in Science and Engineering at MIT are women, 29% of graduate students, and 17% of the Science and Engineering faculty. This is the drop-off I mentioned that constitutes the leaky pipeline (45% to 29% to 17%). This picture can be divided into two distinct segments. For the century ending in the mid 60s to early 70s - fewer than 5% of MIT undergraduates and PhD students were women (except during the two World Wars), and there were no women faculty in Science and Engineering. Then suddenly, the student curves begin a dramatic rise in the late 1960s-early 70s and, the faculty curves begin to rise above zero and then increase in the 1970s. Why? 2 Figure 1. The percent of MIT undergraduates and graduate students who are women, and the percent of MIT Science and Engineering Faculty who are women as a function of time. Almost all students who come to MIT major in Science or Engineering, so curves for students in just those fields are very similar to curves for all students. The reason to use data for all students is that these data were collected back to 1901 while data for just Science and Engineering students has only been collected since the early 1990s. The percent of science and engineering students only who are female as of today is given in the text. The dotted orange line represents data gathered at a different time than data represented by the solid orange line. `The turning point was the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and subsequent affirmative action laws; and the women’s movement, which altered people’s thinking about the role of women in society. But why were there no women on the Science and Engineering faculty for the first 100 years? After all, a few women got PhDs as early as the 1920s. I don’t know the answer for MIT specifically, I wasn’t here, but the following anecdote applies to most universities. When I was a graduate student in the 1960s, I worked summers at the Cold Spring Harbor lab, where I met a woman scientist named Barbara McClintock (Figure 2). I was in my early 20s, Barbara in her late ‘60s. One day Barbara showed me a letter that had been written a number of years earlier (probably in the 1940s) to a biology department chair by a well-known geneticist. 3 The chair was soliciting suggestions for candidates to fill a faculty opening in his department. The geneticist had offered several candidates’ names, and then added. “Of course the #1 person in the world in this field is Barbara McClintock. It’s too bad you can’t hire her because she’s a woman. “ Barbara told me she could not get a faculty job in any university science department, only in home economics departments. Women simply could not get faculty jobs in science departments before the mid 1960s. Fortunately, Barbara managed to get a job as a research scientist at CSH with support from the Carnegie Foundation. Oh, by the way, at age 81 Barbara McClintock won the Nobel prize in medicine. Figure 2. Barbara McClintock (1902-1992). I mention this story because we think of science as a meritocracy, and to a large degree, it is. But Barbara McClintock’s story shows that societal beliefs can overpower merit. You could be the best in the world and still not be hired. In 1964 it became illegal to deny women access to jobs based on their gender. In addition, the number of women Science and Engineering majors began to climb nationally, as did the number of graduate students. Women began to be hired onto Science and Engineering faculties. People assumed it was just a matter of time until women would comprise half the Science and 4 Engineering faculty. But that was not what happened, as Figure 3 shows in greater detail for women Science faculty at MIT. Figure 1 shows the percent of women faculty in Science and Engineering combined. Figure 3 shows the number of women faculty just in the 6 current departments of Science at MIT as a function of time. Figure 3. The number of women faculty in the 6 departments in the School of Science. The number of men in selected years is indicated across the top. In 1960, there were no women faculty in the 6 current departments of Science at MIT. Women began to be hired in the mid 1960s. By 1970 there were 2 women and 264 men. Then, after 1971, the number of women shoots up by a factor of 10. Why? 1971 saw the implementation of the affirmative action regulations under the ’64 Civil Rights Act, “the Schultz regs” named after then US Secretary of Labor George Schultz. The Schultz regs required universities to submit written plans to hire women, and do so, or risk losing their federal funding. Women were hired because the Civil Rights Act removed the barrier to their being hired, and then federal law mandated it. I was approximately # 10 (1973). I was superbly trained and had done very visible research as a graduate student at Harvard. 5 Had I been a man and applied for the job I almost certainly would have been hired. But I had not even thought of applying for a faculty position. I was actively recruited by MIT and Harvard - for my credentials, of course, but, I assume, in part because it was the law. You’ll notice that after this curve got up to about 20 women faculty – hence about 7-8% of the Science faculty – it pancaked for 20 years. If you were to plot a graph of the number of women faculty in Engineering it would be almost super-imposable on this curve during this early period. It begins in ‘64 (with the hiring of Sheila Widnall) then shoots up in 1973-74 to reach 10 women faculty before plateauing for a decade. I’ll come back to these plateaus and to forces that drove the curves up again. But first, a major conclusion from this historical view. Why did I tell you all this ancient history? Here’s why: In retrospect, it’s obvious that not being able to get a job is a serious barrier to women’s advancement. Equally clear is that 1964 and the early ‘70s were a turning point that threw open the doors of universities and other workplaces to women. But what we did not know then, what is not easy to see, and what has taken us nearly 50 years to understand is that on the other side of that 1964 wall were a series of obstacles to women’s advancement that were unanticipated and largely invisible. Furthermore, some of these obstacles were almost as effective at excluding women as the fact that a woman couldn’t get a job at all. Identifying these invisible gender-based obstacles and removing them takes about 30 years. When you realize that there wasn’t just one but several, its easy to see why the pipeline leaked and women’s progress to the top has been slow. I’ll next describe how key obstacles were identified and removed. I’ll keep a running list so by the end we will have a reasonably complete explanation for the leaky pipeline. So far we have just the one (obvious) obstacle: Before 1964 women couldn’t be hired (Figure 4). 6 EXPERIENCES OF WOMEN AT THE LEAD-EDGES OF THE CURVES To explain how barriers to women’s advancement were identified, I turn to the experiences of the pioneers on the front of those waves of undergraduates, graduate students, and faculty shown in Figure 1. What were the experiences of these women who began to pour into the system in the early 70s? Soon after I arrived at MIT in 1973 I met Mary Rowe (Figure 5). She had been appointed by President Wiesner and then-Chancellor Paul Gray, at the request of the few women faculty who had arrived several years before me, to deal with issues that were already affecting female students and faculty. Figure 5. Mary Rowe, ombudsperson, MIT. Mary Rowe became a pioneer in women’s issues at MIT and in the US. When we met she was grappling with an issue I had never heard of called “sexual harassment”. She told me that female students were having a difficult time dealing with professors who wanted to date them. I didn’t understand immediately the seriousness of this problem. Put men and women together in the work place, what did they expect? Nor did I think that I had ever experienced sexual harassment as an undergraduate. It took me some years to realize that perhaps I had. 7 For example, when I was an undergraduate at Harvard, I was sitting at my lab desk one day writing up notes when the door of the lab flew open. There stood a scientist I didn’t know but recognized instantly. Before I could rise and shake hands, he had zoomed across the room, stood behind me, put his hands on my breasts and said, “What are you working on?” It was Francis Crick, the codiscoverer of the structure of DNA. Did I feel harassed? Not at all. I was very embarrassed, but for him, not for myself. My challenge was to figure out how to focus Crick’s attention on my lab notebook without offending him. What I did not grasp ‘til years later was that a man who treats a student that way may not be genuinely interested in her lab notes. Fortunately, Mary Rowe and the MIT administration did understand the implications of such behavior in the work place and set about changing it. You can look up the term “sexual harassment” in Wikipedia and read about MIT’s role in this. Meanwhile, activist lawyers, like the great Catherine McKinnon of Michigan, established in court that sexual harassment constituted illegal gender discrimination under Titles VII and IX of the Civil Rights Act, because it made it impossible for women to be equal in the work place. Today, federal law requires every workplace to post a set of rules to prevent sexual harassment or risk being sued. MIT recruited Professor Jay Keyser to develop MITs rules and implement their enforcement. From start to finish, it took about 30 years to all but eliminate sexual harassment from classrooms and workplaces. This time-frame is typical for most work-place barriers women have encountered: 30 years! And by the way, even after the problem was 98% solved, you couldn’t repeal the law and throw away the rule-book. You have to continue to enforce the rules. You don’t suppose sexual harassment could have driven some young women from the science and engineering academic pipeline do you? Put it on the list! (Figure 6) What happened to women when they got to graduate school? Answer? Dearth of mentoring. When I was a graduate student I had never heard of formal mentoring programs at Harvard. Presumably mentoring happened as a matter of course when most students looked like the faculty, or in the case of some women like me, when women were lucky enough to find fabulous male mentors. Mine was Jim Watson, the co-discoverer, with Crick, of the structure of DNA! (Jim was a much more hands-off mentor.) Without Jim’s support I doubt I could have become a scientist. But it turned out that many women students did not find mentors. Formal mentoring programs had to be devised and implemented. You don’t think lacking a mentor who encourages you to become a scientist and helps you to do so could possibly have had anything to do with women leaving the academic pipeline, do you? Put it on the list! (Figure 6) And by the way, although the women at the lead-edge of the wave were the first to encounter these obstacles, women didn’t leave them behind as they 8 advanced to the next stage of their careers. Rather the barriers were cumulative! Well, if you were a young woman who was lucky enough not to be derailed by sexual harassment, and you found a powerful male mentor who pushed you along, were you home free? Uh, no. During the transition from getting a PhD to joining the faculty was when young women were likely to encounter what I thought, when I was young, was the only barrier to women’s advancement in Science: the family-work problem (Figure 6). Figure 6. Obstacles that slowed women’s progress to the top in academic Science and Engineering in the US When I was a student and postdoc at Harvard I noticed there were almost no women on the Science faculty and I thought I knew why. I could see that high-level science – the only type I was interested in – required that you work 70+ hours a week. The postdocs then were nearly all men, many already married with wives who stayed home to care for their children. How could you possibly be the kind of scientist I aspired to be and be a mother? I found a simple solution to the problem. After obtaining my PhD and doing a postdoc, I got divorced. Just to be on the safe side, I decided not to remarry and not to have children. So much for that problem. 9 Well, now that you are experts in identifying invisible gender-related obstacles to women rising to the top, you will have doubtless divined that what most of us saw then as a woman’s choice (to have children or not to have children) was not really much of a choice at all: institutions in which high-level science was done, were “gendered”: men and women had different assigned roles. Men were expected to work night and day and support the family, women to abandon their jobs and work full time at home to support the man at work. That was the system in the 1950s, 60s 70s, 80s, 90s. In fact, we are still grappling with the residue of this system today even though it long-ago ceased to reflect the reality of, or serve young people’s lives. Did women – or men - really have a choice? Certainly not an equal choice. It didn’t occur to many of us that this was a barrier that someone should remove on our behalf. I thought it was a biological reality, thus a woman’s choice. So daunting was this particular obstacle that for decades, women instinctively knew that at work they should never talk about pregnancy or children for fear people might think they were not serious about science. You wanted to be sure people knew that you were happy to be a ‘nun of science’. And, in fact, personally, I was. The question of whether having to decide to have children or not contributed to the leaky pipeline is rhetorical. We know it did, and still does. And studies by Mary Ann Mason and Marc Goulden at Berkeley have confirmed that having children causes women to leave the academic pipeline preferentially. This barrier belongs on the list. Well, is that it? Were there any more barriers for women who wanted to be part of this fabulous world of science and engineering? Who weren’t derailed by sexual harassment, who were lucky enough to find great mentors, and who were wiling to forgo having children? There was one more and it took many of us 20 years on the faculty to understand it. I’ll tell the story from a personal point of view because I was involved with other women at MIT in identifying and addressing this obstacle. THE FINAL BARRIER? Like many women of my generation, I joined the MIT faculty in 1973 believing that the Civil rights Act, affirmative action laws, and the women’s movement had eliminated gender discrimination. I certainly didn’t expect to experience it. I fled from feminists. Over the next 15 years, I learned I was wrong. Gender discrimination still existed. I figured it out by watching how other women were treated. What I saw was that when a woman and a man made scientific discoveries of equal importance, neither her discovery nor the woman was valued equally to the man’s discovery or the man. Sometimes the woman got no credit at all. She was invisible. 10 These observations were almost impossible to believe. Science is a meritbased occupation. So how could this be true? But after many years of watching – through the 70s, 80s, into the 90s - how women faculty’s scientific contributions were treated relative to men’s, I was certain that women and their science were undervalued. Amazingly, it took me 20 years to know it was even true of me – not just other women. (Which is called denial.) The realization of this strange truth was very demoralizing. Sometimes I wanted to quit science (alas I couldn’t afford to.) I came to feel my life had been a failure. I had cheerfully given up a lot to join a profession I loved, but I came to realize I would never be accepted no matter what I discovered. Worse, I believed I was the only person on earth aware of this strange truth. You couldn’t tell anyone. Who would believe you? Plus, they would assume – as I always had - that if you complained of bias, it must mean you weren’t good enough. If you were really good enough – if you discovered the structure of DNA for example they would have to give you the Nobel prize and you would be accepted as equal. Right? Alas, as I finally realized, if you were a woman you could make a Nobel-prize-level discovery and quite possibly not win the Nobel prize, or even be viewed as having done critically important work. In time, it dawned on me that this strange truth I had discovered might be the most important scientific discovery I had made. It was so important that it deserved a Nobel prize. What I did not know – and would not learn for another decade – was that the discovery I had made so painstakingly over 20 years had long since been made! (see Figure 7) Furthermore, in 2002 a Nobel prize was awarded for a version of this discovery. Figure 7. Unconscious gender bias It was psychologists, not biologists, who had discovered the phenomenon in the 70s and 80s by a series of remarkable experiments. Their research 11 demonstrated the irrationality of the human brain to make accurate judgments or see truths that contradict our unconscious biases and beliefs. In the case of gender bias, the result of unconscious bias is to judge identical accomplishment as less good if we think it was done by a woman. For a related finding involving irrational decisions the 2002 Nobel prize in economics went to the psychologist Kahneman. As for unconscious gender bias, another very surprising thing is that the belief that women are less good than men persists whether the judges are men – or women. Both under value identical work when it is done by a woman. There are enormous consequences to unconscious bias in the work place. It can affect many aspects of the job: how a person is treated, their compensation, whether they are hired in the first place. Here is one typical example of the effect of unconscious bias from my era that relates to teaching. When I was a young professor a colleague asked if I would like to co-teach an important undergraduate core course with him. I agreed. He said he would ask the chairman for his approval. A few days later my colleague came back to say that the chair had said, “No,” because, although I was thought to be a good teacher, he knew that MIT undergraduates ‘would not be able to believe scientific information spoken by a woman.’ I knew instantly the Department Head was right and I was extremely grateful to him for sparing me a potential disaster. What I find odd today is that this knowledge did not open our eyes to the serious consequences of the unconscious undervaluation of women’s competence in so many of their academic duties. I shrugged it off as simply the way the world was - and I happily continued to teach the undergraduate lab course that was taught almost exclusively by women faculty in that era. Do you think unconscious gender bias and the undervaluation of women’s work could contribute to the leaky pipeline? or to the failure to hire women unless novel efforts are made to see beyond our unconscious tendency to undervalue their accomplishments? Put it on the list! (Fig. 8). Alas, I did not know about the psychology research. Meanwhile, I had reached the end of the line. I was struggling to do research I was very excited about. Despite being a tenured professor, I could not get minimal space and resources I needed, and which I knew were available to my male colleagues. I decided to take my case up though the MIT administration until I found someone who would listen. But happily, along the way, I mustered the courage to tell a female colleague what I had learned. I chose Mary-Lou Pardue, a biologist I admired for her wisdom and her exceptional scientific accomplishments. To my utter amazement, she had discovered the same thing I had! We looked at each other and said, you don’t suppose there could be others, do you? We inventoried the tenured women faculty in the 6 departments of Science so we could ask them, and we made the startling discovery that in 1994 there were only 15 tenured women, 197 tenured men! I said check the back of the catalogue, maybe they list the women separately? We found 2 women in Engineering with joint appointments in Science and added them to our list. 12 The small number made for an easy poll. Very quickly, 16 of the 17 women signed a letter to Bob Birgeneau, then Dean of Science, informing him there was systemic, largely invisible, and almost certainly unconscious, bias against women faculty. We asked him to convene a committee to document the problem so he could fix it. The committee was formed (essentially secretly, since, like me, these women scientists did not want to be seen as radicals). The committee interviewed all the tenured and most of the untenured women faculty and collected data. We found that as women progressed through their careers from junior faculty to tenured professors, they were gradually marginalized: excluded from access to resources and to professional activities, rewards and compensations that make MIT such a superb and envied environment in which to do science. This exclusion rendered the women’s jobs more difficult and less gratifying. The women also, of course, noted their tiny number on the Science faculty: just 8%. They suggested that the negative experiences many of them had had might even contribute to these small numbers of women, since female students often told them: “I don’t want to be like you”. As one woman remarked, “Who could blame them? Neither do I!” The word that came to summarize the women’s experiences was Marginalization. Figure 8. Obstacles list In response to this report, then Dean of Science Bob Birgeneau immediately corrected many inequities and recruited a few women faculty to administrative roles in Science. And, importantly, he said “the answer to this problem is more women.” Birgeneau quickly identified top women scientists 13 around the country and went to get them. It worked (Figure 9). We call this increase in the number of women faculty in Science the “Birgeneau bump”. Figure 9. Increase in number of women faculty in Science that resulted from Dean Birgneau’s response to a confidential report of the Committee on women faculty in Science in 1996. The original women in Science were thrilled and returned to their labs. Importantly, the Committee continued to study the status of women in Science. I stepped down as Chair of the Committee and Professor Molly Potter took over. And there was more to come. The story of what happened several years later, in 1999, has been told many times, including in a book commemorating MIT”s 150th anniversary in a chapter by Professor Lotte Bailyn, who chaired the MIT faculty in 1999 (Figure 10). Lotte asked us to write a summary of our committee’s findings for the MIT Faculty News Letter. The story got to the press and was reported by Kate Zernike on the front page of the Boston Globe and by Carey Goldberg on the front page of the NYTimes. The reaction to it from outside MIT overwhelmed us. We were inundated with e-mail from women across the country saying they too had experienced the same problems but that no one would listen to them. 14 Figure 10. As described in the book “Becoming MIT”, in 1999, Professor Lotte Bailyn, then chair of the MIT faculty, asked that a summary of the internal report of the Committee on the Status of Women Faculty in Science be written for publication in the MIT Faculty News Letter. I believe there were two reasons this report had such an impact - besides the fact it had articulated an apparently near-universal workplace issue for women: Most important, Charles Vest, the President of MIT, had read the women’s report, believed it was true, and decided to endorse it publicly at a time when most institutions denied and suppressed similar claims by their women faculty. To accompany the FNL article Vest wrote: “I have always believed that contemporary gender discrimination within universities is part reality and part perception. True, but I now understand that reality is by far the greater part of the balance.” Now that was an MIT moment of decision. The second reason the report received so much attention was because of the scientific stature of the women who had documented the discrimination. Figure 11 shows just a few of the accomplishments as of 2010, of the 16 women faculty in Science who wrote to Dean Birgeneau in 1994 to ask him to establish the Committee on women faculty relative to all male full professors of Science at MIT in 2010. Three of the women have won the US National Medal of Science, and nearly 70% are members of the NAS or NAE (or both). When someone complains of discrimination it is often assumed or said that they really aren’t good enough. No one could say that about these women without looking 15 downright silly. Many of these women were hired in the 1970s as a result of the Schultz regs. Figure 11. Some accomplishments of the 16 women faculty in Science who wrote to Dean Birgeneau in 1994 to complain of systemic, unconscious bias against women faculty. HOW MIT ADDRESSED THE PROBLEMS IN THE 1999 REPORT After so much publicity MIT was on the hot seat to find long-term solutions to the problems the women had discovered. First it replicated the study in the other MIT Schools. In Engineering, Professor Lorna Gibson chaired a committee that obtained very similar results to those in Science. The Dean of Engineering at the time, Tom Magnanti quickly stepped in to fix inequities and hire more women by devising innovative recruiting methods and search procedures (Figure 12). Figure 12. Professor Lorna Gibson chaired a Committee on the Status of Women Faculty in the School of Engineering that issued a report to the Dean in 2002. 16 But how do you fix all these issues long term, and embed solutions in the policies, practices and culture of MIT so that the problems don’t come back? As Figure 13 shows, these are hard problems to fix. Figure 13. Problems identified by the Committees on the Status of Women faculty in Science at MIT in 1995-1999. MIT’s approach was to appoint women who had worked on this issue into the central administration to work with the powerful administrators – the President, Provost and Deans – with the authority to write new policies for family leave, track equity for women faculty, monitor fairness in hiring, and so forth. The administrative structures President Vest and Provost Brown put in place and the relationship of these to the structure of the central administration are shown in Figure 14. I was appointed to the Academic Council (the highest level administrative committee at MIT) and I Co-Chaired a Council on Faculty Diversity with the Provost. I met regularly with women faculty who chaired 5 committees (one in each of the five Schools ) and who in turn met with the Deans of the Schools to review salaries and address inequities that might arise. Figure 14. Structure of the MIT central administration (white boxes) and of committees established by Vest and Brown (grey boxes) to address the problems shown in Figure 13. 17 Figure 15 shows some of the key people who worked on these problems in the Vest administration. Figure 16 shows some of the accomplishments of this work. Figure 15. Some members of the Vest administration who dealt with the issues in Figure 14. Figure 16. Some accomplishments during the Vest administration in addressing issues shown in Figure 13. But we knew it would take longer than one administration to remedy all these things. What would happen in the transition from Vest’s administration to Hockfield’s? Particularly in recruiting, since a faculty only turns over every 35 years, and thus you have to track hiring for decades. The answer is that the process not only continued, it was expanded and strengthened by three new positions in the administration. One is Associate Provost who sits on the Academic Council. In addition, the Deans of Science and Engineering appointed Associate Deans to address these issues among others. Figure 17 shows key players in President Hockfield and Provost Reif’s administration who continued and expanded the work begun under President Vest and Provost Brown to increase the numbers and ensure equity for women faculty in Science and Engineering. Figure 18 shows some of the accomplishments of these individuals under the Hockfield administration. 18 Figure 17. Key players in President Hockfield-Provost Reif’s administration who have addressed issues for women faculty at MIT. Figure 18: Some accomplishments of the Hockfield administration that have advanced the status and numbers of women faculty in Science and Engineering at MIT. Perhaps most important of these has been to bring many proactive administrators and colleagues to the fore. That a male physics chair, Professor Ed Bertschinger, proposed a symposium to celebrate women scientists and leaders, and that MIT should select it for this occasion is in itself a reflection of the extraordinary accomplishments of the Hockfield administration and its commitment to women (Figure 19). Thank you Ed, and thank you President Hockfield and Provost Reif. 19 Figure 19. Proactive administrators and male colleagues have come forward in the HockfieldReif administration and work with women faculty to advance these issues. Particularly important has been the increase in the number of women faculty in the Schools of Science and Engineering at MIT during the Hockfield administration. Figure 20 shows the data for the School of Science again indicating the reason for the recent rise in numbers. Figure 20. Number of women faculty in the 6 departments of Science at MIT. The numbers of men for some years are shown across the top. The impact of Dean Kastner and Associate Dean Sive’s efforts are indicated. Once again, some people may ask about quality, after what are now three substantial affirmative efforts to recruit women in the School of Science since 20 1964. Figure 21 provides evidence that the women hired at MIT continue to be of the same extraordinary level of accomplishment as their male colleagues (the percents of men and women in the National Academy are not significantly different given the small numbers involved.) Figure 21. A measure of the accomplishments of female and male faculty in Science at MIT, 2010. The numbers of women faculty in the School of Engineering have increased similarly, thanks to Dean Subra Suresh, Associate Provost Barbara Liskov, and Associate Dean Cynthia Barnhart. The accomplishments of the women faculty in Engineering are also exceptional, like those of their male colleagues. Figure 22. Numbers and some accomplishments of women faculty in the School of Engineering at MIT, 2011. So, where are we today? There are many women in the MIT academic administration of Science and Engineering (vs zero when we began); there are more than twice as many women faculty as in the mid ‘90s; equity is reviewed on 21 a continuous basis; it has become routine for women to take family leave, have children, and get tenure; department heads work to include women faculty so they are not marginalized etc. Essentially all recommendations made in the 1999 and 2002 reports on women have been achieved to at least a significant degree. And have these changes made MIT a more welcoming environment for women scientists and engineers than a dozen years ago? In honor of this symposium, it was decided to find out by interviewing all the women faculty in Science and Engineering in 3 groups: women who had participated a decade ago in the original study, women who received tenure after the earlier studies; and junior women faculty. The results are summarized in the report that was issued last week and made available at this symposium (Figure 23.) Drum roll, please! Figure 23. A Report on the Status of Women Faculty in Science and Engineering at MIT in 2011. The Report was the work of two committees, one chaired by Professor Hazel Sive (Science) and one chaired by Professors Lorna Gibson and Barbara Liskov (Engineering.) The results show remarkable change! Older women faculty are perhaps the most impressed because they have seen such dramatic change. But the best news of all is that so many of the women who came after us love MIT, and feel privileged and excited to work here, as they should. Representative quotes from the report are shown in Figure 24. 22 Figure 24: Quotes form the 2011 Reports on the Status of Women Faculty in Science and Engineering at MIT So: Is everything fixed? Well, I hope I have convinced you that that would not be possible. As you know, it takes 30 years to remove one of these barriers that have hindered women’s advancement, and years of monitoring after that. And MIT is only 12-15 years into this effort. These efforts must continue for at least 15 years. And indeed, problems persist. Which is why MIT’s accomplishment is cause for a celebration, but with a few caveats. And what are the problems that remain that we learned about from this report? Some are lesser versions of old problems. For example, today many women faculty teach core courses in Science and they receive superb student evaluations for their teaching. However, some women faculty report that some students still show more respect for male than female faculty. Some are new problems arising from changes in society, for example, the two career couple. In my generation women followed their husbands and hoped to find jobs if possible, or they simply did not marry. But today, both partners in a couple are often employed and plan to remain so. Some problems that were reported in 2011 arise from solutions that were designed to address earlier issues. As my last topic, I’d like to address just one problem that emerged from the interviews in all three groups of women faculty. Indeed, we have heard this from our female postdocs, graduate students and even our undergraduates. It is a fascinating problem, and I believe may reflect the problem that underlies much of what I have been talking about today. The issue is the perception that when women advance, they must have done so through some unfair advantage or a lowering of the standards - when 23 they were hired, when they got tenure, when they win prizes - and the negative impact this false perception can have on women’s confidence. I hope you will agree from my talk that there are two kinds of affirmative action: one was designed decades ago to increase diversity by temporarily lowering requirements for certain schools and jobs. That kind of affirmative action is actually illegal now. Furthermore, it never existed in faculty recruitment at MIT (except possibly in the era when only men could be hired.) Instead, as I showed, a second type of affirmative action was needed, first, to end the prohibition against hiring women, and then to recruit exceptional female candidates. Why does it take special, different effort to hire women if they are just as good as men? Why doesn’t it just happen on its own? (1) Because there are fewer women in the pipeline so it is more work to find them; (2) Because we may overlook women since we can undervalue them even when they are as good or better than male candidates; and (3) Because for a variety of reasons women many not apply unless they are asked. Why does it bother women to have people insinuate that they were hired due to affirmative action? Does it matter? This is another study we don’t have to do. The psychologists have already done it. It turns out, tell a man he was hired due to affirmative action he will say, “So what, I’m the best person for the job.” Tell a woman the same thing and you can seriously undermine her confidence. Why? Because, psychologists believe, both men and women suffer the unconscious bias that women really are less good than men. Hinting women were hired because of affirmative effort reinforces this unfounded, unconscious, and destructive bias. But why would anyone believe that women who get tenure at MIT are less good than men? Particularly when the data so clearly show it isn’t true? Where does this insidious belief come from? To answer a question that difficult, you have to go up-river to Harvard and ask that brilliant economist, university administrator, and my good friend, Larry Summers. His hypothesis that women have less “intrinsic aptitude” for science math and engineering fields was a stunning public declamation of where this problem come from: from us, from the society around us. There is not one shred of credible scientific evidence that any group of people is “intrinsically” ie genetically inferior in any intellectual activity required for Science and Engineering – least of all women. And not for lack of research on the topic. This is not a scientific belief but bias. I think it is not unreasonable to ask whether promulgating a belief in the genetic inferiority of women – or any group - in schools or workplaces should – like sexual harassment – be illegal under Title VII and Title IX of the Civil Rights act, since it creates and reinforces an unequal playing field. Would this whole problem disappear if MIT stopped conscious institutional efforts to recruit women and stopped talking about it? Absolutely not. Bias would still be present, unconsciously influencing judgments. The only defense is to 24 keep putting it on the table and deal with it, as the new report on women faculty wisely does. It’s the unfounded unconscious bias itself that needs to change – men’s and women’s undervaluation of women, and women’s undervaluation of themselves is perhaps the last barrier to overcome. And we know we have to keep attacking this problem because even freshmen women today ask us: “How should I deal with male classmates who tell me I only got into MIT because of affirmative action?” These young women tell us this attitude began when they were in high school. Clearly, our job will not be done until society sees women’s equal academic achievements as equal. The biased view of women contributes to leaks in the pipeline even before students get to college –especially in the physical sciences and math. How will we know when we have succeeded? When 50% of Congress is women, for starters. Having seen such extraordinary change at MIT in just a dozen years, I now hope to see this happen in my life time. In closing, I hope you’ll agree that we understand quite well the leaky pipeline and the under-representation of women at the top of science and engineering fields, and we know too how scientists and engineers can lead by example in the solution of what is in truth a broad societal issue. Thank you. 25