The death of God in Auschwitz - LJY

advertisement

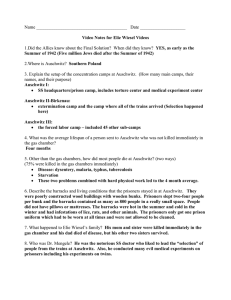

Weekly Chinuch Article – c.1300 BCE-1945 CE: The Death of God in Auschwitz-Birkenau – by Robin Moss Behind me, I heard the same man asking: “Where is God now?” And I heard a voice within me answer him: “Where is He? Here He is—He is hanging here on this gallows...” That night the soup tasted of corpses. Elie Wiesel – Night (1958) I have just returned from my first trip to Poland. I went with an adult group from Birmingham Progressive Synagogue, and we spent three days exploring the Jewish history of Kraków. What we did was nothing new – the Poland trip, especially to Kraków with its iconic Jewish quarter (Kazimierz) to learn about pre-war Jewish life, followed by the obligatory trip to Auschwitz-Birkenau (broken up by a visit to the rather remarkable, if entirely non-Jewish-story, Wieliczka Salt Mines), has become almost a rite of passage for many Jews. Indeed, with over a million visits a year, Auschwitz-Birkenau appears to now be solidly on the non-Jewish tourist trail too. My day at Auschwitz I and then Birkenau (Auschwitz II) will rank as one of the most emotionallycharged, soul-destroying, life-affirming, intelletually-challenging and identity-forming of my life. If you have never been, please go. Maybe not now. Maybe not soon. But go. I was always scared I wouldn’t be ready to face what is a truly awful place. I wasn’t ready. But I will never be – nobody will. What happened there was quite simply anti-human. Birkenau especially is like a scar on the face of the human world – a man-made hell. I don’t want to go into the history of the camp. I’m sure you know much of it anyway, and if you don’t, go on Wikipedia (or better – read a comprehensive Holocaust history. I can thoroughly recommend The Destruction of the European Jews by Hilberg). What I am interested in is the question, which I had always thought I understood, but which, standing in front of the ruins of a gas chamber (one of four at Birkenau) that could murder two thousand people at once, with my blood running cold, a lump in my throat and an immense sense of emotional vulnerability, I suddenly had to confront even more starkly: did God die in this place? Elie Wiesel in Night famously declared God died in the Auschwitz. You can see what he means – why would a good God allow this catastrophe to happen? Rabbi Jonathan Sacks responds that for him, it wasn’t his belief in God that died in Auschwitz, but his belief in humankind. God was there all the time, intervening in tiny ways to allow the miracles of survival, whilst the perpretators’ humanity shows why we need to abandon our sense that people are inherently good. Nice try, wouldn’t there have been other ways to intervene that would have been subtle but in keeping with a good God? For example, perhaps God could have sent freak weather that put the gas chambers out of action for the duration of the war. That would be a God I could believe in (maybe). Not the God who let millions be murdered in cold blood “in exchange for” allowing a few inmates to survive. Even if we invoke free will as an argument against God intervening to stop the slaughter, surely the curtailment of the free will of millions of victims (by virtue of their social exclusion, imprisonment, brutal treatment and/or death) should be balanced up against intervention to prevent this happening? Another Rabbi, Richard Rubenstein, argued in the 1960s that God had indeed died in Auschwitz, in the sense that the idea of a convenantal relationship between the Jewish people and God (formed by Abraham, deformed and destroyed by Adolf) was no longer tenable. But Rubenstein was not an atheist – his God was simply not a God of history. As the title of his book indicates, After Auschwitz belief in that God had to come to an end. This might seem like quite an attractive idea. Many people, on scientific grounds for example, already have a sense that God is in some way “distant” – that God leaves the world be, acting only as the setter-in-motion of the world (or possibly the tweaker-of-the-natural-laws). Why not just add to this a moral “distance” – that God is no longer the guarantor of good? I suppose my problem with this is that it leaves God as, well, really nothing much at all. As a response to the Holocaust, to simply say that God cannot be the God of history seems unsatisfactory. It seems to either be so obvious as to be banal or so limiting of God as to be atheism. Where does that leave me? Frustrated, I suppose. Going to Auschwitz-Birkenau makes me feel more strongly than ever that there is such a thing as absolute good; it is the opposite of what I encountered at that place. If I want, I can call this thing “God” – the terminology that Judaism has always used. But at the same time, I cannot help but agree with Wiesel. What kind of God – what kind of innate human goodness – would allow the building a place like that, and murder over a million people there in a few dozen months? Unlike Rabbi Sacks, I cannot give up on humankind – it’s all I’ve got to hold on to. Unlike Rubenstein, all I see without the God of history (/goodness of humans within history) is despair. And I’m not (yet) willing to give in to despair. Chinuch articles do not necessarily represent the opinions or views of Liberal Judaism or LJY-Netzer. If you are interested to learn more about the Shoah or Jewish history in Poland, email robin@liberaljudaism.org for more details about March of the Living, a unique opportunity for Bogrim to be part of an extraordinary trip with over 10,000 participants from all over the world. 3rd-9th April; £175