I think that the authors should show the mean and

advertisement

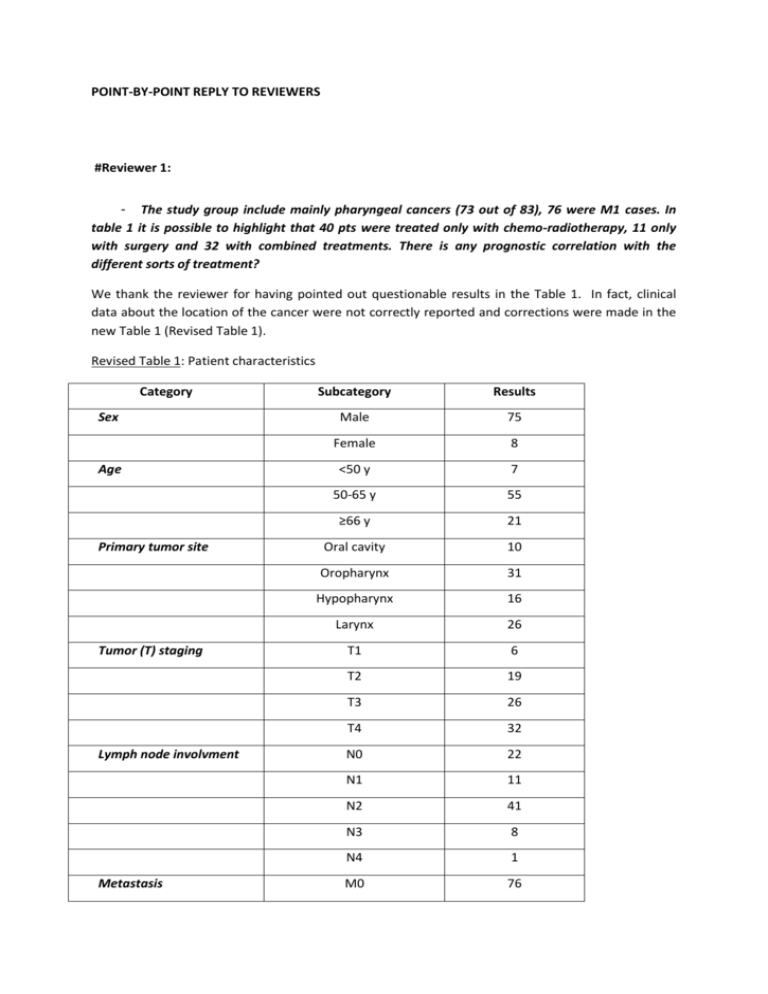

POINT-BY-POINT REPLY TO REVIEWERS #Reviewer 1: - The study group include mainly pharyngeal cancers (73 out of 83), 76 were M1 cases. In table 1 it is possible to highlight that 40 pts were treated only with chemo-radiotherapy, 11 only with surgery and 32 with combined treatments. There is any prognostic correlation with the different sorts of treatment? We thank the reviewer for having pointed out questionable results in the Table 1. In fact, clinical data about the location of the cancer were not correctly reported and corrections were made in the new Table 1 (Revised Table 1). Revised Table 1: Patient characteristics Category Sex Age Primary tumor site Tumor (T) staging Lymph node involvment Metastasis Subcategory Results Male 75 Female 8 <50 y 7 50-65 y 55 ≥66 y 21 Oral cavity 10 Oropharynx 31 Hypopharynx 16 Larynx 26 T1 6 T2 19 T3 26 T4 32 N0 22 N1 11 N2 41 N3 8 N4 1 M0 76 M1 7 Surgery 8 Chemoradiotherapy 35 Surgery+chemoradiotherapy 39 None 1* Positive 14 Negative 59 Not determined 10 Treatment HPV status *: this patient denied the treatment. Otherwise, patients who were treated by surgery alone or combined with chemoradiotherapy had a better overall survival than patients treated by chemoradiotherapy alone as shown in Revised Figure 1. This figure was added in the revised manuscript as Figure 3. Revised Figure 1: - Any data on the presence of HPV? Because of the cancers location this could be a very important issue. We totally agree with the reviewer that it is an important issue. Therefore, we added the HPV status as requested: HPV status was estimated by anti-p16 immunostaining on 73 patients out of 83. No sample was disposable for the remaining 10 patients due to the small size of the biopsies. 59 patients out of 73 were negative and 14 patients out of 73 were positive for p16 staining (Revised Table 1). The HPV status analysis is now integrated in the Material and Methods section, and the results are included in Table 1 in the revised manuscript. Authors should better present and discuss clinical data of their group of patients. We modified the Table 1 and precisions were added in the clinical presentation. We did not focus on the prognostic value of the clinical parameters (sex, age, primary tumor site, TNM staging) listed in Table 1 as it was not the aim of the current study. In addition, we and others have already addressed their prognostic value in head and neck cancers, and we found that the TNM classification was correlated with overall survival whereas sex, age and primary tumor site had no impact on clinical outcome (Tartour, Deneux et al. 1997; Tartour, Mosseri et al. 2001). # Reviewer 2: - The authors should better clarify the choice of the analyzed markers, in particular ephrineA1 and SCINDERIN. The reviewer is correct in his/her comment. We have therefore rephrased the paragraph referring to this issue as follows: “We have previously reported that increased expression of EPHRIN-A1 and SCINDERIN in tumor cells was involved in their resistance to CD8+T cell-mediated lysis by a mechanism linked to actin cytoskeleton remodelling [26,39]. While previous studies have shown increased expression of EPHRIN-A1 in head and neck cancers [40], the expression of SCINDERIN remains unknown in these cancers. Since we have observed that CD8+T cell infiltration in head and neck cancer had no prognostic significance [22], this study was designed to address whether the expression of markers involved in the resistance to cytotoxic CD8+T cells such as EPHRIN-A1 and/or SCINDERIN or the down-modulation of HLA-class I molecules could explain the absence of clinical outcome of intratumoral CD8+T cell infiltration in head and neck cancer.” - The authors underline that ephrine-A1 and SCINDERIN are deregulated in several tumors. Specify where they are aberrantly expressed. Specify whether the ligand and its receptor expression are directly related or not. With respect to the deregulated expression of EPHRIN-A1and its receptors and of SCINDERIN in different cancer models, this is now specified in the introduction section of the revised manuscript as follows: “EPH receptor tyrosine kinases and their EPHRIN ligands constitute a large cell communication system with the ability of generating bidirectional signaling: forward signals in EPH-receptor expressing cells and reverse signals in EPHRIN ligand-expressing cells [31]. These signals can result in cytoskeleton reorganization, cell adhesion or cell separation. Paradoxical observations regarding expression of EPH receptors and EPHRINS in cancer have been reported. Indeed, the up and downmodulation of several EPH receptors and EPHRINS expression have been described in different types of cancers compared to their healthy tissues of origin [31]. The upregulation of EPHRIN-A1 in hepatocellular carcinoma promoted the proliferation and the expression of genes associated with proliferation and invasion [32]. The expression of EPHRIN-A1 and its major receptor EPH-A2 were both augmented and found to be significantly associated with worse prognosis in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma where they correlated with shorter survival [33]. Greater expression of EPHRIN-A1 and EPH-A2 were also found in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary gland and correlated with the tumor stage [34]. However, unbalanced expression of EPHRIN-A1 and EPH-A2 was reported in several cancers such as glioblastoma where in the absence of EPHRIN-A1, EPH-A2 becomes a substrate for Akt, promoting cell migration and invasion [35]. The oncogenic properties of EPH and EPHRIN signaling have also been analyzed. In this respect, EPH-dependent signals have been reported to have tumor suppressive functions [36-38]. SCINDERIN is a member of the geslolin family of actin-severing proteins which regulate the actin cytoskeleton by severing pre-existing actin filaments, capping filaments ends and nucleating actin assembly from monomers in a calcium-dependent manner [39, 40]. The SCINDERIN has been reported to play a role in exocytosis by mediating disruption of F-actin cortical network, whereas the other members of the gelsolin family, such as gelsolin, contribute to cell motility. An anti-tumor role for SCINDERIN has been described based on its capacity to induce differentiation and apoptosis in megakaryoblastic leukemia that overexpress SCINDERIN [41]. In contrast, increased expression of SCINDERIN has recently been related to resistance of bladder tumor cells to cisplatin via inhibition of mitochondria-mediated apoptosis [42]. We have previously reported that increased EPHRIN-A1 and SCINDERIN expression in tumor cells conferred resistance to CD8+T cell-mediated lysis by a mechanism linked to actin cytoskeleton remodeling [26, 43]. While previous studies have shown increased expression of EPHRIN-A1 in head and neck cancers [44], the expression of SCINDERIN remains unestablished in these tumors. Our previous observations in head and neck cancer indicated no prognostic significance for CD8+T cell infiltration [22, 30]. Considering this, the present study was designed to address whether the expression of proteins involved in the resistance to cytotoxic CD8+T cells such as EPHRIN-A1 and/or SCINDERIN or the downmodulation of HLA-class I molecules, could explain the absence of clinical impact of intratumoral CD8+T cell infiltration in head and neck cancer.” .“ - The authors should complete the list of other cytokines and ligand-receptors involved in Cancer cell death mediated by T cytotoxic cells. The requested changes have been made in the revised manuscript as follows: “T cell infiltration is emerging as novel type of cancer biomarker based on the host immune response. Tumor-infiltrating cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, in particular, are capable of mediate directly the death of tumor cells via the release of cytokines (IFN, TNF), cytotoxic factors (perforin, granzyme) or the engagement of ligand-receptor interactions from the TNF family (TRAIL-TRAIL-R, FasL-Fas, TNFTNF-R) [7, 8].” - Patient selection: the treatments consisted of chemo-radiotherapy without surgery, surgery combined or not with chemo-radiotherapy, but these treatments are not coherently reported in the relative table. Please change it. As requested by the reviewer, the number of patients treated by surgery only, chemo-radiotherapy only, combination of both, or not treated is now indicated in Table 1 in the revised manuscript as follows (Revised Table 1): Revised Table 1: Patient characteristics Category Sex Age Primary tumor site Tumor (T) staging Subcategory Results Male 75 Female 8 <50 y 7 50-65 y 55 ≥66 y 21 Oral cavity 10 Oropharynx 31 Hypopharynx 16 Larynx 26 T1 6 T2 19 T3 26 T4 32 N0 22 N1 11 N2 41 N3 8 N4 1 M0 76 M1 7 Surgery 8 Chemoradiotherapy 35 Surgery+chemoradiotherapy 39 None 1* Positive 14 Negative 59 Not determined 10 Lymph node involvment Metastasis Treatment HPV status *: this patient denied the treatment. - Immunohistochemistry: Why was the IHC analysis performed only on frozen tissue and not on FFPE? At the beginning of the study, we made different tests with the anti-EPHRIN-A1 antibody using frozen and FFPE samples. The results obtained with frozen samples were far more reproducible and easier to be interpreted. We decided therefore to use frozen sections for all the study and for all the antibodies. - Immunohistochemistry score: I do not understand how the CD8 expression could be expressed in term of percentage, since it is not related to tumoral population. Correct these and re-evalute accordingly the statistical data. We do agree with the reviewer’s comment. The CD8 staining was only present on the CD8+T cells and never observed on the tumoral cells. CD8+ population was evaluated in percentage over the cells in the stroma (which surrounded the carcinoma). The count was also based on reference staining slides. To be clearer in our description, we modified the Materiel and Method section as follows: “A semi-quantitative grading system was used to quantify EPHRIN-A1 and HLA-class I expression by tumor cells. The staining was scored as 0 (less than 10% positive cells), 1 (10-20% positive cells), 2 (21-50% positive cells), 3 (more than 50% positive cells) based on reference staining slides using a high magnification (x400). A semi-quantitative grading system was also used to quantify tumor infiltrating CD8+T cells. The staining was scored as 0 (less than 10% positive CD8+T cells in the stroma), 1 (10-20% positive CD8+T cells in the stroma), 2 (21-50% positive CD8+T in the stroma), 3 (more than 50% positive CD8+T cells in the stroma). As previously reported, the cut-off for high and low expression group was arbitrarily set up as > or < 20% positive staining cells respectively [30]. For SCINDERIN expression, only the presence (scored as 1) or the absence (scored as 0) of its expression by tumor cells was recorded.” I think that the authors should show the mean and median expression values of all markers. The variables (CD8, EPHRIN-A1, SCINDERIN, HLA-class I expression) were scored only semiquantitatively. As they were recorded as a qualitative but not quantitative parameter, we could not give the mean and median values for each parameter. - - The figure of the western blot analysis of SCINDERIN expression show an aspecific line in the first position. We agree that there is a slight aspecific band in the control cells (empty vector) as compared to the cells transfected with the SCINDERIN expressing vector. We therefore performed an immunofluorecence staining using the same anti-SCINDERIN antibody (Sigma-aldrich; 2.75 g/ml), the IGR-Heu cell line that have a low expression level of SCINDERIN and the IGR-Heu derived IGRHeuR8 cells that constitutively overexpress SCINDERIN (Abouzahr, Bismuth et al. 2006). As shown in Revised Figure 2, the antibody clearly stained the SCINDERIN-overexpressing IGR-HeuR8 cells and provided a very faint staining for the low SCINDERIN-expressing IGR-Heu cells. This figure can be included in the revised manuscript. Revised Figure 2: IGR-Heu and IGR-HeuR8 non small cell lung carcicnoma cells were fixed (PFA, 4%) and permeabilised (SDS, 0.1%). They were then stained with anti-SCINDERIN antibody (1h, room temperature) followed by adequate secondary conjugated-antibody (45 min, room temperature). Nuclei were labelled using TO-PRO®-3 Iodide (blue). - In the table some important clinical-pathological are reported but they are not included in the statistical analysis. Why? We have analyzed the impact of the mode of therapy on clinical outcome and we found that patients who were treated by surgery alone or combined with chemoradiotherapy had a better overall survival than patients treated by chemoradiotherapy alone (Revised Figure 1). We did not focus on the prognostic value of the clinical parameters (sex, age, primary tumor site, TNM staging) listed in Table 1 as it was not the aim of the current study. In addition, we and others have already addressed their prognostic value in head and neck cancers, and we found that the TNM classification was correlated with overall survival whereas sex, age and primary tumor site had no impact on clinical outcome (Tartour, Deneux et al. 1997; Tartour, Mosseri et al. 2001).We added these data and the figure below in the result section of the revised manuscript . Revised Figure 1: - Clarify and summarize through an additional table, the different marker expression and assess whether there is a relationship between them. The number of patients for each marker expression is now indicated in Table 2 in the revised manuscript and as follows (Revised Table 2): Revised Table 2: Number of patient for each marker expression CD8 HLA-class I EPHRIN-A1 SCINDERIN 0 6 32 33 74 1 38 38 12 9 2 21 12 6 3 18 1 32 Except for SCINDERIN, a marker expression of 0 to 1 is considered as low, and of 2 to 3 as high. We had already assessed whether there was a statistical correlation between CD8 and HLA class-1 markers. Using various cut-offs, we did not find any correlation between HLA-Class I molecules (detected by the W6/32 mAb) and the CD8+T cell infiltration (Revised Table 3 and data not shown). The details of our analysis is below: Revised Table 3: Number of patients based on HLA-class I and CD8 expression using two different cut-offs. HLA-class I low (0-1) High (2-3) CD8 low 0-1 38 6 CD8 high 2-3 32 7 P = 0.62 HLA-class I Score 0 Score 1-2-3 CD8 low 0-1 15 29 CD8 high 2-3 17 22 P = 0.3 - There are several inconsistencies: "CD8 \ MCH1" missing 11 patients; "ephrina \ CD8" there are 93 patients, but they should be 83. We do apologize for these inconsistencies. The appropriate corrections have been made in the revised manuscript. REFERENCES: Abouzahr, S., G. Bismuth, et al. (2006). "Identification of target actin content and polymerization status as a mechanism of tumor resistance after cytolytic T lymphocyte pressure." Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103(5): 1428-1433. Tartour, E., L. Deneux, et al. (1997). "Soluble interleukin-2 receptor serum level as a predictor of locoregional control and survival for patients with head and neck carcinoma: results of a multivariate prospective study." Cancer 79(7): 1401-1408. Tartour, E., V. Mosseri, et al. (2001). "Serum soluble interleukin-2 receptor concentrations as an independent prognostic marker in head and neck cancer." Lancet 357(9264): 1263-1264.