(King & Bennett) to the Great Depression

advertisement

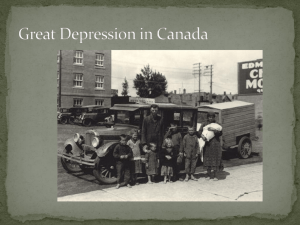

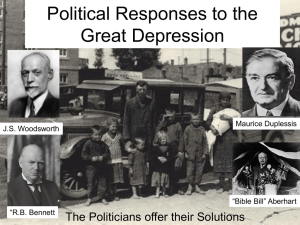

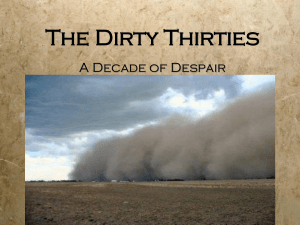

Canada’s response to the Great Depression The roots of the Depression in Canada and the rest of the world can be traced to the economic changes that followed World War One. Only the United States would emerge from the First World War in a position of relative economic strength. As such, much of the world owed money to the U.S. The economic boom that was gathering pace in the United States throughout the early 1920s eventually pulled the Canadian economy out of its postwar slump. However, this led to Canada’s economy to become heavily dependent on the U.S. economy: 1. US capital (money and factories) permeated nearly all aspects of the Canadian economy, making Canada very vulnerable to instability in the US. 2. Moreover, Canada heavily relied on exports to the U.S.: a) Minerals such as zinc and cooper (used in production of cars in the U.S.) b) Pulp and paper (used in newspaper production in the U.S.) c) Automobiles (produced in Canada by U.S. companies) d) Grains such as wheat (exported to the U.S.) This growing instability was dramatically accelerated by the stock market crash of October 1929. Although the Toronto Stock Exchange did not suffer a calamity the scale of that which happened to its New York counterpart, the vast amount of US capital invested in the Canadian economy meant that the effects of the New York stock crash were soon felt in Canada. The Depression of the 1930s was not the first economic slump to hit Canada. What would set the Great Depression apart from the other slumps were its severity, scope, and length. The fact that it was coupled with one of the most severe droughts in Canadian history, only served to spread the misery and make recovery more difficult. In the years between 1929 and 1933: Exports fell by about 50% Wheat prices fell by about 75% Unemployment reached about 25% William Lyon MacKenzie King (1926-1930) MacKenzie King and his Liberal party beat the Conservative party in the federal elections in 1925. The Depression set upon Canada during MacKenzie King’s second term in office as Prime Minister. King, like his counterpart Hoover in the White House, was initially at a loss at what to do about the stagnating economy. Other economic slumps had occurred in King’s lifetime, but they had proven temporary. King therefore approached the early stages of the Depression cautiously. When he was pressed for government action to alleviate the growing misery, he hid behind the British North America Act. King claimed that the type of action required was constitutionally the responsibility of the provinces and not the federal government. But he then refused to increase subsidies (gift of money) to provincial governments- because most of them were Conservative. He believed that this fiscally conservative approach was what prudent Canadians expected of him, and he took this faith to the polls in 1930. King miscalculated. The Conservatives, under the leadership of R.B. Bennett, won a majority government on promises of action and relief. Richard Bedford Bennett’s response to the Depression (1930-1935) Once in office, Bennett increased tariffs by 50% and allocated $20 million for relief programs. All at once he pushed prices higher with the tariff and gave people money (relief) to cope with the higher prices- in broad terms a zero net gain. Bennett's first plan was to raise tariffs on imported goods from foreign countries. In theory, this would protect manufacturers. He believed that raising tariffs on imported goods from foreign countries would convince other nations to lower tariffs on Canadian goods. Other nations retaliated by raising tariffs on imported goods from Canada. Unfortunately the side effects of his plan produced more damage than good. That policy was disastrous as Canadian exports plummeted from $1.4 billion in 1929 to $475 million in 1933. The relief “system” that Bennett developed in the early 1930s consisted of a patchwork of municipal, provincial and federal efforts. The system of relief, such as it was, consisted of federal and provincial funds making their way into municipal coffers from where they would be redistributed to those in the most need. Initially, most were “work for relief” schemes of public works, but this eventually gave way to direct relief. Between 1932 and 1936 the federal government established UNEMPLOYMENT RELIEF CAMPS. Run by the Department of Defense, the camps paid the men 20 cents a day for construction work. In 1935 a protest against poor conditions in the camps culminated in the Regina Riot - the most violent episode of the 1930s, in which one policeman was killed, dozens of men were injured and 130 arrested. At the federal level, Prime Minister Bennett established a number of other measures to fight the symptoms of the Depression: Example 1: The Farmer’s Creditors Arrangement Act: A law to help debt-ridden farmers restructure their loans. Example 2: The Bank of Canada: Canada’s first central bank. It was designed to coordinate the government’s monetary policy. For the first four years, Bennett’s approach to the economic crisis was largely consistent with his belief in the free enterprise system and that people, not the government, are ultimately responsible for their own wellbeing. The federal and provincial funds were not enough to sustain the growing numbers of people in need. Unemployment peaked in 1933, at 26.6%. Those figures did not include the thousands of out-of-work farmers and fishers, who were not counted in government statistics. Nor did it include the thousands who had simply given looking for work. Bennett was called the “Nadir of Depression” and became the source of endless jokes. Cars that had to be towed by horses, because gasoline could not be afforded, were called "Bennett Buggies". As the Canadian economy limped into the fifth year of the Depression in 1935, Bennett shocked many in the country and his own party by advocating ta more comprehensive and aggressive approach to the crisis. Taking a cue from Roosevelt’s plan, this package became known as Bennett’s New Deal. Bennett’s New Deal didn't work primarily because it was too late. The country did not have any confidence in Bennett’s leadership after five years of misery and no progress. Much of the legislation that was eventually enacted as part of that program was declared unconstitutional by the courts two years later. Therefore Bennett’s New Deal never had the time that it needed to possibly make a difference. It could not save the Conservatives or Bennett's place in politics. Many former Conservative part voters turned to three newly created small parties. King and the Liberals won the election of 1935 and were in power again. Bennett continued ineffectively as an opposition leader until 1938 when he left Canada and moved to England. The Return of King (1935-1948) Popular disaffection with Bennett was widespread by October 1935, when voters gave King’s Liberals a resounding victory. Although King gave the impression of sympathy with progressive and liberal causes, he had no enthusiasm for the New Deal of American President Franklin D. Roosevelt (which Bennett tried to emulate), and he never advocated massive government action to alleviate depression in Canada. Mackenzie King refused, for the most part, to provide work for the jobless and insisted that their care was primarily a local and provincial responsibility. King did not continue Bennett’s New Deal and the courts declared it unconstitutional in 1937. Thus without the serious intervention of the federal government, the Depression continued to linger on under the leadership of King. King, believing that the way to end the depression was to stimulate international trade and end the high tariff wars with the U.S., signed the new reciprocity agreement with the United States. U.S.Canadian trade subsequently grew dramatically, but in the short- term the depression continued. King’s government reorganized and strengthened the government-owned radio network (renamed the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.) Entertainment of the 1930s, not surprisingly, tended to be escapist. Radio broadcasts of music, drama, and comedy became the staple fare for most Canadian families. Canadians also tuned in by the millions to listen to Foster Hewitt's hockey broadcasts. "Hello hockey fans in Canada and Newfoundland....” was the signature opening line. In the 1930s, Ice Hockey established itself as an enduring national sport in Canada. On September 9, 1939, nine days after Germany’s invasion of Poland, Canada’s Parliament declared war on Germany. The vote was nearly unanimous, a result that rested on the assumption that there was to be a “limited liability” war effort that would consist primarily of supplying raw materials, foodstuffs, and munitions. As a result of WWII, Canada saw a massive growth in the federal government, bringing a surge of government spending and a vast increase in the civil service. The massive government spending, which acted as an economic stimulus, finally reduced unemployment to minimal levels by 1942.