Dust_2.7 - University of Utah

advertisement

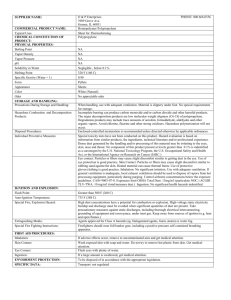

Episodic Dust Events along Utah’s Wasatch Front W. JAMES STEENBURGH AND JEFFREY D. MASSEY Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT THOMAS H. PAINTER Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, CA In preparation for submittal to Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology Draft of Tuesday, February 09, 2016 Corresponding author address: Dr. W. James Steenburgh, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Utah, 135 South 1460 East Room 819, Salt Lake City, UT, 84112. E-mail: jim.steenburgh@utah.edu Abstract Episodic dust events cause hazardous air quality along Utah’s Wasatch Front and dust loading of the snowpack in the adjacent Wasatch Mountains. This paper presents a climatology of episodic Wasatch Front dust events based on surface-weather observations from the Salt Lake City International Airport (KSLC), GOES satellite imagery, and the North American Regional Reanalysis. Dust events at KSLC, defined as any day (MST) with at least one report of a dust storm, blowing dust, and/or dust in suspension (i.e., dust haze) with a visibility of 10 km (6 mi) or less, average 4.3 per water year (WY, Oct–Sep), with considerable interannual variability from 1930–2010. The monthly frequency of dust-events is bimodal with primary and secondary maxima in Apr and Sep, respectively. Dust reports are most common in the late afternoon and evening. An analysis of the 33 most recent (2001–2010 WY) events at KSLC indicates that 16 were associated with a cold front or baroclinic trough, 11 with airmass convection and related outflow, 4 with persistent southwest flow ahead of a stationary trough or cyclone over Nevada, and 2 with other synoptic patterns. GOES satellite imagery and backtrajectories from these 33 events, as well as 61 additional events from the surrounding region, illustrate that emissions sources are mostly concentrated in the deserts of southern Utah and western Nevada, including the Sevier dry lake bed, Escalente Desert, and Carson Sink. Efforts to reduce dust emissions in these regions may help mitigate the frequency and severity of hazardous air-quality episodes along the Wasatch Front and dust loading of the snowpack in the adjacent Wasatch Mountains. 2 1. Introduction Dust storms impact air quality (Gebhart et al. 2001; Pope et al. 1995), precipitation distribution (Goudie and Middleton, 2001), soil erosion (Gillette 1988; Zobeck 1989), the global radiation budget (Ramanathan 2001), and regional climate (Nicholson 2000, Goudie and Middleton 2001). Recent research regarding regional hydrologic and climatic change produced by dust-radiative forcing of the mountain snowpack of western North America and other regions of the world has initiated a newfound interest in dust research. (Hansen and Nazarenko 2004; Painter et al. 2007; Painter et al. 2010). For example, observations from Colorado’s San Juan Mountains indicate that dust loading increases the snowpack’s absorption of solar radiation, thus decreasing the duration of snow cover by several weeks (Painter et al. 2007). Modeling studies further suggest that dust-radiative forcing results in an earlier runoff with less annual volume in the upper Colorado River Basin (Painter et al. 2010). Synoptic and mesoscale weather systems are the primary drivers of global dust emissions and transport. Mesoscale convective systems that propagate eastward from Africa over the Atlantic Ocean produce half of the dust emissions from the Sahara Desert, the world’s largest Aeolian dust source (Swap et al. 1996; Goudie and Middleton 2001). Dust plumes generated by these systems travel for several days in the large-scale easterly flow (Carlson 1979), with human health and ecological impacts across the tropical Atlantic and Caribbean Sea (Goudie and Middleton 2001; Prospero and Lamb 2003). In northeast Asia, strong winds in the post-coldfrontal environment of Mongolian Cyclones drive much of the dust emissions (Yasunori and Masao 2002; Shoa and Wang, 2003; Qian et al., 2001). The highest frequency of Asian dust storms occurs over the Taklimakan and Gobi Deserts of northern China where dust is observed 200 d yr-1 (Qian et al., 2001). Fine dust from these regions can be transported to the United 3 States, producing aerosol concentrations above National Ambient Air Quality Standards (Husar et al. 2001; Jaffe et al., 1999; Fairlie et al., 2007) The Great Basin, Colorado Plateau, and Mojave and Sonoran Deserts produce most of the dust emissions in North America (Tanaka and Chiba, 2006; see Fig. 1 for geographic and topographic locations). Most land surfaces in these deserts are naturally resistant to wind erosion due to the presence of physical, biological, and other crusts (Gillette et al., 1980). However, these crusts are easily disturbed, leading to increased dust emissions, in some cases long after the initial disturbance (e.g., Belnap et al. 2009). Based on alpine lake sediments collected over the interior western United States, Neff et al. (2008) found that dust loading increased 500% during the 19th century, a likely consequence of land-surface disturbance by livestock grazing, plowing of agricultural soils, and other activities. Several studies suggest that the synoptic and mesoscale weather systems that generate dust emissions and transport over western North America vary geographically and seasonally. In a dust climatology for the contiguous United States, Orgill and Sehmel (1976) proposed several including convective systems, warm and cold fronts, cyclones, diurnal winds, and specifically for the western United States, downslope (their katabatic) winds generated by flow-mountain interactions. They identified a spring maximum in the frequency of suspended dust for the contiguous United States as a whole, which they attributed to cyclonic and convective storm activity, but found that several locations in the Pacific and Rocky Mountain regions have a fall maximum. However, they made no effort to quantify the importance of the differing synoptic and mesoscale systems. In Arizona, Brazel and Nickling (1986, 1987) found that fronts, thunderstorms, cutoff lows, and tropical disturbances (i.e., decaying tropical depressions and cyclones originating over the eastern Pacific Ocean) are the primary drivers of dust emissions. 4 The frequency of dust emissions from fronts is highest from late Fall–Spring, thunderstorms during the summer, and cutoff lows from May–Jun and Sep–Nov. Dust emissions produced by tropical disturbances are infrequent, but are likely confined to Jun–Oct when tropical cyclone remnants move across the southwest United States (Ritchie et al., 2011). For dust events in nearby California and southern Nevada, Changery (1983) and Brazel and Nickling (1987) also established linkages with frontal passages and cyclone activity, respectively. In addition to synoptic and mesoscale systems, these studies also cite the importance of land-surface conditions (e.g. soil moisture, vegetation) for the seasonality and spatial distribution of dust events. None of these studies, however, have specifically examined the Wasatch Front of northern Utah, where episodic dust events produce hazardous air quality in the Salt Lake City metropolitan area and contribute to dust loading of the snowpack in the nearby Wasatch Mountains (Fig. 2). From 2002–2010, wind-blown dust events contributed to 13 exceedances of the National Ambient Air Quality Standard for PM2.5 or PM10 in Utah (T. Cruickshank, Utah Division of Air Quality, Personal Communication). Dust loading in the Wasatch Mountains affects a snowpack that serves as the primary water resource for approximately 400,000 people and enables a $1.2 billion winter sports industry, known internationally for the “Greatest Snow on Earth” (Salt Lake City Department of Public Utilities 1999; Steenburgh and Alcott 2008; Gorrell, Salt lake tribune, 2011). This paper examines the climatological characteristics and emissions sources during Wasatch Front dust events. We find that Wasatch Front dust-events occur throughout the historical (1930–2010 water year1) record, with considerable interannual variability. Events are driven primarily by strong winds associated with cold fronts or airmass convection, with the 1 Hereafter, all years in this paper are water years (Oct–Sep). 5 deserts and dry lake beds of southern Utah, as well as the Carson Sink of Nevada, serving as primary regional emission sources. Dust emission mitigation efforts in these regions may reduce the frequency and severity of related hazardous air quality events along the Wasatch Front and dust loading of the Wasatch Mountain snowpack. 2. Data and methods a. Long-term climatology Our long-term dust-event climatology derives from hourly surface weather observations from the Salt Lake City International Airport (KSLC), which we obtained from the Global Integrated Surface Hourly Database (DS-3505) at the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC). KSLC is located in the Salt Lake Valley just west of downtown Salt Lake City and the Wasatch Mountains (Fig. 1) and provides the longest quasi-continuous record of hourly weather observations in northern Utah. The analysis covers 1930–2010 when 97.9% of all possible hourly observations are available. The hourly weather observations included in DS-3505 derive from multiple sources, with decoding and processing occurring at either operational weather centers or the Federal Climate Complex in Asheville, NC (NCDC 2001, 2008). Studies of dust events frequently use similar datasets (e.g., Nickling and Brazel 1984; Brazel and Nickling 1986; Brazel and Nickling 1987; Brazel 1989; Hall 1981; Orgill and Sehmel 1976; Changery 1983; Qian 2002; Yasunori and Masao 2002; Shao et al. 2003; Song et al. 2007; Shao and Wang 2003). Nevertheless, while hourly weather observations are useful for examining the general climatological and meteorological characteristics of dust events, they do not quantify dust concentrations, making the identification and classification of dust somewhat subjective. Inconsistencies arise from observer biases, changes in instrumentation, reporting guidelines, and processing algorithms. 6 These inconsistencies result in the misreporting of some events (e.g., dust erroneously reported as haze) and preclude confident assessment and interpretation of long-term trends and variability. Consistent with World Meteorological Organization (WMO) guidelines (WMO 2009), the present weather record in DS-3505 includes 11 dust categories (Table 1). During the study period, there were 916 blowing dust (category 7), 178 dust-in-suspension (category 6), 7 dust storm (categories 9, 30–32, and 98) and one dust or sand whirl report (category 8) at KSLC. There were no severe dust storm reports (categories 33–35). Amongst the blowing dust, dust-insuspension, and dust storm reports, there were 69 with a visibility > 6 statute miles (10 km), the threshold currently used by the WMO and national weather agencies for reporting blowing dust or dust-in-suspension (Shao et al. 2003; Federal Meteorological Handbook, 2005). Since these events are weak, or may be erroneous, they were removed from the analysis. This includes all but one of the 7 dust storm reports. The dust or sand whirl report was also removed since we are interested in widespread events rather than localized dust whirl(s) (a.k.a. dust devils). The resulting long-term dust-event climatology is based on the remaining 1033 reports. A dust event is any day (MST) with at least one such dust report. b. Characteristics of recent dust events The analysis of the synoptic, meteorological, and land-surface conditions contributing to Wasatch Front dust events concentrates on events at KSLC during most recent ten-year period (2001–2010). This enables the use of modern satellite and reanalysis data, and limits the number of events, making the synoptic analysis of each event tractable. Resources used to synoptically classify dust events, composite events, and prepare case studies include the North American Regional Reanalysis (NARR), GOES satellite imagery, Salt 7 Lake City (KMTX) radar imagery, and hourly KSLC surface weather observations and remarks from DS-3505. The NARR is a 32-km, 45-layer reanalysis for North America based on the National Centers for Environmental Predication (NCEP) Eta model and data assimilation system (Mesinger et al. 2006). Compared to the ERA-Interim and NCEP-NCAR reanalysis, the NARR better resolves the complex terrain of the Intermountain West, but still has a poor representation of the basin and range topography over Nevada (see Jeglum et al. 2010). We obtained the NARR data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Operational Model Archive Distribution System (NOMADS) at the National Climatic Data Center web site (http://nomads.ncdc.noaa.gov/#narr_datasets), the level-II KMTX radar data from NCDC (website: http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/nexradinv/), and the GOES data from the NOAA Comprehensive Large Array-Data Stewardship System (CLASS, http://www.class.ncdc.noaa.gov). c. Dust emission sources We identify dust emission sources during from 2001–2010 using a dust-retrieval algorithm applied to GOES satellite data. Because the algorithm only works in cloud-free areas and many dust events occur in conjunction with cloud cover, we expand the number of events to include those identified in: (1) DS-3505 reports from stations in the surrounding region with at least 5 years of hourly data (Fig. 1), (2) the authors’ personal notes, and (3) Utah Avalanche Center annual reports. This analysis is thus not specific to KSLC, but does identify emissions sources that contribute to dust events in the region. Our dust-retrieval algorithm is a modified version of that described by Zhoa et al. (2010) for MODIS. First, we substitute the GOES 10.7 μm channel for the MODIS 11.02 μm channel. 8 Then the two reflectance condition thresholds used to identify the presence of clouds from the MODIS .47, .64, and .86 μm channels are replaced by a single threshold (.35) that uses the only visible channel on GOES. Finally, the maximum threshold for the brightness temperature difference between the 3.9 and 11 μm (11 and 12 μm) bands was changed from -.5 ºC to 0 ºC (25 ºC to 10 ºC). These adjustments enable the identification of visible dust over Utah using GOES data, although uncertainties arise near cloud edges, when the sun angle is low, or when the dust concentrations are low or near the surface. The algorithm is applied every 15 min during the daylight hours (0700–1900 MST), with plume origin and orientation identified subjectively. 3. Results a. Long-term climatology Dust events at KSLC occur throughout the historical record, with an average of 4.3 per water year (Fig. 3). Considerable interannual variability exists, with no events reported in seven years (1941, 1957, 1981, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2007) and a maximum of 15 in 1934. No effort was made to quantify or assess long-term trends or interdecadal/interannual variability given the subjective nature of the reports and changes in observers, observing methods, and instrumentation during the study period. Based on current weather observing practices (Glickman 2000; Shao and Wang 2003), the minimum visibility when dust is reported meets the criteria for blowing dust [1 km (5/8 statute mi) < visibility ≤ 10 km (6 statute mi)], a dust storm [0.5 km (5/16 statute mi) < visibility ≤ 1km (5/8 statute mi)], or a severe dust storm [visibility ≤ 0.5 km (5/16 statute mi)] in 95.40%, 9 2.59%, and 2.01% of the dust events, respectively (Fig. 4)2. Therefore, only a small fraction of the dust events and observations meet dust storm or severe dust storm criteria. To integrate the effects of event severity, frequency, and duration into an estimate of the annual near-surface dust flux, we first estimate the dust concentration, C (µg m-3), for each dust report following equations (6) and (7) presented in Shao et al. (2003): C = 3802.29Dv-0.84 Dv< 3.5 km C = exp(-0.11Dv + 7.62) Dv ≥ 3.5 km where Dv is the visibility. Multiplying by the wind speed and integrating across all observation intervals yields an estimated mean annual near-surface dust flux of 399.4 g m-2, with a maximum of 2810.2 g m-2 in 1935 (Fig. 5). Because it integrates event severity, frequency, and duration, the annual near-surface dust flux provides a somewhat different perspective from the annual number of dust events (cf. Figs. 3 and 5). For example, 1934 featured the most dust events, but the greatest near-surface dust flux occurred in 1935. In 2010, there were only 2 dust events, but also a pronounced decadal-scale maximum in annual near-surface dust flux. The monthly distribution of dust events is bimodal, with primary and secondary peaks in Apr and Sep, respectively (Fig. 6). Similar peaks are observed in the near-surface dust flux, but with an additional peak in Jan (Fig. 7). This Jan peak is surprising, but careful examination of the data revealed one unusually strong multiday event in January of 1943 that contributed to 83% of the Jan monthly mean. In the summer, the dust flux minimum is distinctly lower compared to the dust-event frequency (cf. Figs. 6 and 7), suggesting that summer dust events are shorter and weaker. From Mar–May, which usually encompasses the climatological snowpack snow water 2 The visibility observations are taken and stored in statute miles, but approximate metric thresholds are used hereafter. 10 equivalent maximum and beginning of the spring runoff, the mean three-month dust flux is 237 g m-2, 59% of the annual flux. Similar bimodal or modal distributions with a primary or single spring dust peak have been identified in the Taklimakan desert of China, southern Great Plains of the United States, Mexico City, and the Canadian Prairies (Yasunori and Masao 2002; Stout 2001; Jauregui 1989; Wheaton and Chakravarti 1990). The spring peak appears to be the result of erodible landsurfaces combined with a high frequency of wind events driven by cyclones and fronts. In fact, the bimodal distributions of dust-events and dust-flux at KSLC is very similar to that of Intermountain cold fronts and cyclones, which are strongest and most frequent in the spring, and have a secondary peak in the fall (e.g., Shafer and Steenburgh 2008; Jeglum et al. 2010). These Intermountain cold fronts and cyclones produce persistently strong winds capable of generating dust emissions and transport during favorable land-surface conditions. Interestingly, dust was reported at KSLC within 3 h of the passage of 12 of the 25 strongest cold fronts identified by Schafer and Steenburgh (2008). The mean wind speed during dust reports at KSLC is 11.6 m s-1 (with a standard deviation of 4.0 m s-1), slightly higher than the 8.5 m s-1 and 9.29 m s-1 found by Holcombe et al. (1997) for Yuma, AZ and Blythe, CA, respectively. Therefore, we use 10 m s-1 as an approximate threshold velocity for dust emissions and transport. At KSLC winds ≥ 10 m s-1 are most common in Mar and Apr, with an additional, but relatively weak, maxima in Aug and Jan (Fig. 8). The Mar and Apr peak resembles the springtime peak in dust events and flux, but the lack of a fall secondary maximum and winter minimum suggests other factors related to seasonal changes to vegetation, soil conditions, and soil moisture (Neff et al., 2008, Belnap et al., 2009, Gillette, 1999) contribute to the seasonality of dust events and fluxes. 11 Dust reports exhibit a strong diurnal cycle and are most common in the late afternoon and evening hours (Fig. 9), as observed in other regions (Jauregui 1989; Mbouro et al. 1997). The frequency of winds ≥ 10 m s-1 at KSLC is about three times higher in the afternoon than morning (Fig. 10), which is consistent with the development of the daytime convective boundary layer. The peak for winds ≥ 10 m s-1 occurs at 14 MST, roughly four hours earlier than the peak in dust reports; a likely consequence of the time needed for dust to travel from its source to KSLC. The frequency distribution of wind directions during dust events is bimodal, with peaks at southerly and north-northwesterly (Fig. 11). About 50% of the time, the wind is from the southsouthwest through south-southeast and about 28% of the time the wind is northwesterly through northerly. Dust flux is also greatest for winds from the south-southwest through south-southeast (Fig. 12), even more so than the frequency, suggesting events with southerly winds transport more dust. b. Recent (2001–2010) events To characterize and classify dust events, we concentrate on a subset of events from 2001– 2010 enabling the use of modern reanalysis, satellite, and radar data in an effort to synoptically diagnosis each event. The monthly frequency distribution of these 33 recent dust events resembles that of the long-term climatology except for a disproportionately high number of summer events (cf. Figs. 6, 13). Based on synoptic analysis, we classified these recent dust events into one of four groups depending on their primary mechanism for dust emissions and transport: (1) airmass convection, (2) cold fronts or baroclinic troughs, (3) upstream stationary fronts or baroclinic troughs, and (4) other mechanisms (Table 2). Here we define baroclinic trough as a pressure trough, cyclonic wind shift, and an insufficiently strong temperature gradient to be called a front. The 11 (33%) 12 events generated by airmass convection featured a thunderstorm, thunderstorm in the vicinity, or squall comment in the DS-3505 reports within an hour of the dust observation, or nearby convection evident in satellite or radar imagery without strong nearby 700-hPa baroclinicity in NARR analyses. These events tended to be shortlived, usually < 2 h, and all occurred between the middle of May and the middle of September. An airmass convection event on May 19th, 2006 reduced visibilities to 6.4 km and lasted for only 17 minutes. At 16 MST KSLC reported a 5 m s-1 southerly wind, the strongest reported wind thus far that day, but at 16:07 MST, seven minutes later, winds increased to 24.1 m s-1 with a gust to 27.7 m s-1 and dust was reported along with a squall at or within sight of the station comment. This dramatic wind shift was associated with an outflow boundary from a convective cell visible on radar imagery at 16:05 MST (Fig. 14a). The weak returns present over KSLC are likely associated with the leading edge of the outflow boundary. Weak large scale forcing is present during this event, as is the case for most airmass convection events. A 17 MST NARR dynamic tropopause analysis, which acts as a proxy for the upper level flow, shows KSLC centered under an upper level ridge (Fig. 14b). Unfortunately, NARR data only extends to 100 hPa so all levels of the two potential vorticity unit (PVU) dynamic tropopause > 100 hPa are forced to 100 hPa. 700 hPa winds were also weak, generally around 5 m s-1, and were associated with limited 700 hPa baroclinicity (Fig. 14c) and 850 hPa height depressions (Fig. 14d) signaling very weak lower tropospheric large scale forcing. In fact, compared to climatology, all airmass convection events have only slightly higher 700 hPa winds (Fig. 17a) and a slight affinity for southerly wind directions (Fig. 17b). The height of the Planetary Boundary Layer (PBL) is similar to climatology (Fig. 17c) preventing higher winds at higher levels from being fully realized at the surface. The climatological variables occurred on the nearest NARR 3 h time step for all days within the month of the dust 13 event. Event and climatological variables were area-averaged from 37N to 41N and 112W to 114W, roughly corresponding to western Utah south of KSLC. 16 (48%) recent events were produced by cold fronts or baroclinic troughs and they featured a cold front or baroclinic trough passage at KSLC within 24 h of the dust observation, a distinct frontal cloud band in visible satellite images, and evidence of a mobile pressure trough and/or baroclinic zone in lower-tropospheric NARR analyses. Dust is usually reported right around frontal passage. In fact, 48% and 77% of recent dust reports reported dust within an hour and 3 hrs of frontal passage, respectively. Figure 15 shows that most reports (35%) occurred during the hour following frontal passage, no reports occurred 3 hrs post frontal passage, and dust was reported as early as 10 hrs before frontal passage. 4 (25%) out of the 16 events reported dust in the prefrontal environment, 16 (100%) during frontal passage, and two (13%) in the postfrontal environment, where prefrontal and postfrontal describe the conditions three hours before and after surface frontal passage, respectively. On 17 MST May 10, 2004 dust reduced visibilities to 8 km during a frontal passage that dropped temperatures 12.8 C in an hour, and produced consistent southerly surface winds > 13.9 m s-1 during the 6 h period prior to frontal passage. Dust plumes initiated in the prefrontal environment over the Escalente Desert and Milford area a few hours earlier and the eastern edge of these plumes reached KSLC and extended into Idaho at the time dust was first reported (Fig. 16a). Large scale forcing was impressive during this time. The 17 MST dynamic tropopause analysis shows an upper level trough positioned over Nevada with an embedded 30 m s-1 southwesterly jet on that surface directly over KSLC (Fig. 16b). 700 hPa temperature and wind analysis shows confluent winds along a strong baroclinic zone just upstream of KSLC (Fig. 16c), with the leading edge of the baroclinic zone collocated with an 850 hPa height trough directly over KSLC (Fig. 16d). This 14 case is similar to other baroclinic trough or cold front events, which are often associated with upper level troughing to the west of KSLC coupled with a low level pressure minimum, strong baroclinicity, and strong lower tropospheric winds. In fact, the initial 700 hPa wind speeds for all cold front or baroclinic trough events is centered around 15 ms-1 (Figure 17d), which occurs only 4% of the time climatologically, and wind directions are only in the southwest quadrant of the compass (Fig. 17e) meaning dust is only initially transported in southwesterly flow for these events, The height of the planetary boundary layer is also much higher than climatology during dust events (Fig. 17f) allowing strong winds aloft to be better realized at the surface. 4 (18%) events were forced by upstream stationary fronts or baroclinic troughs. The major difference between this group and baroclinic troughs or cold fronts is the trough axis remains quasi-stationary and to the west of KSLC within 24-hrs of the initial dust observation. The event on April 1, 2003 was forced by a stationary trough and produced eight observations of dust between 10 MST and 24 MST that dropped visibilities to as low as 8 km. Winds remained southerly throughout the day, night, and following morning and averaged 9.8 m s-1 for all the dust observations. Unfortunately, clouds were present over most of the region during the event, limiting chances of observing plumes, but Figure 18a shows a small dust plume coming off the Escalente Desert at 13:45 MST. Upper level analysis at 10 MST reveals a strong southwesterly jet centered over northwestern Nevada ahead of an upper level trough offshore of California (Fig. 18b). The leading edge of a 700 hPa baroclinic zone over Nevada has weakly confluent flow that is mainly parallel to the isotherms (Fig. 18c), and an associated 850 hPa trough (Fig. 18d), suggesting the presence of a stationary front or baroclinic trough. To summarize, a cold front or baroclinic trough is present over Nevada, but the lack of upper level support and cross isotherm flow prevents transient motion leaving Utah positioned under persistent large scale 15 southerly flow capable of emitting dust. August 30, 2009 is listed as a stationary baroclinic trough or cold front event, but this event may be erroneous because observer comments and satellite imagery indicate smoke, not dust, likely reduced visibilities. Two (6%) events were associated with other mechanisms. On September 16, 2003 KSLC reported dust in northwesterly flow when a surface front developed downstream of the area putting KSLC in the post-frontal environment. This event did not fit with the other categories because there was no surface frontal passage or stationary boundary. The other event occurred on March 13, 2005 and was forced by an equatorward travelling arctic front. Although there was frontal passage at KSLC, the nature and evolution of an arctic front is very different from intermountain cold fronts and baroclinic troughs so it would be inappropriate to classify it similarly. Past studies suggest soil moisture has a capillary effect on soil grains, which increases the friction velocity of the soil making it less erodible (Saleh and Fryrear 1995; Bisal and Hsieh 1966; Chepil and Woodruff, 1963; McKenna-Neuman and Nickling, 1989). However, Gillette (1999) observed wind erosion 10-30 minutes after a soaking rain because the eroding layer needs only to be a millimeter thick and strong winds can dry a layer that thin very quickly. The NARR soil moisture content is calculated from the soil surface down to 200 cm so it may be an inappropriate proxy for surface dryness. c. Dust emission sources and transport Additional dust days were added to our recent dust day climatology in an effort to locate as many source regions as possible. Hourly dust observations have been reported in accordance 16 with our 10 km visibility and present weather (e.g. no dust whirls) constraints at four different stations across the Intermountain West (IMW) since 2001 (33 at KSLC, 30 at Delta, UT, 18 at Pocatello, ID, 6 at Elko, NV for 87 total, but 79 individual events due to overlap). The dust days from these stations were further supplemented with personal observations of dust along the Wasatch Front, and from Utah Avalanche Center annual reports, bringing the total number of dust days to 94. The characteristics of these events are consistent with the long-term climatology of KSLC in terms of annual, monthly, and diurnal distribution (not shown). Our GOES satellite dust retrieval algorithm is applied to all 94 dust days in an effort to locate all visible dust plumes originating in the IMW. For the 94 dust days, 120 independent plumes were identified during 47 (50%) dust days. The remaining 47 (50%) dust days may not have had any observable plumes because clouds blocked the dust from the satellite detection, the dust occurred at night or during a low sun angle, or the dust concentration was too weak for the detection algorithm to pick it up. Airmass convection events and baroclinic trough or cold front events with two or fewer dust observations were the most common types of dust events without any visible plumes. GOES data indicates the low topographical ancient depositional environments (e.g., ancient lake beds) in southwest Utah and Western Nevada are the primary dust plume emission sources for the IMW. Figure 18 shows the approximate plume origins are mostly clustered in certain lowland regions, most notably the Sevier Desert, Milford Flat area, Escalente Desert, and West Desert in southwest Utah and the Carson Sink in Nevada. Gillette (1999) calls small areas of frequent dust production “hot spots”, which are depositional environments in transitional arid regions that have had their biological and physical crust disturbed. The aforementioned areas receive heavy recreation and agricultural use so the crusts in these areas are likely disturbed. The plumes are mostly oriented from the SSW and SW, indicating that the plumes are mainly 17 transported in southwesterly flow. Only 8.3% of the plumes were directed towards the south and they all originated in Nevada. The length of the plume lines only represents the length of the plume at one particular time step and the lines are not related to plume strength or to the distance the plume traveled. 40 (33%) plumes occurred on Delta, UT dust days, 29 (24%) on KSLC dust days, 10 (8%) on personal notes and UAC annual report dust days, 9 (8%) on Pocatello, ID dust days, 6 (5%) on Elko dust days, and 26 (22%) on dust days reported at multiple stations. Interestingly, many observed plumes are not oriented towards their respective station, and days with visible plumes have an average of 2.55 plumes, meaning there are multiple dust sources throughout the IMW on any given dust day. Not all of the dust we observed on satellite started as a point source. There are 11 cases when large areas of dust showed up on the satellite with no clear origin. The majority of these cases occurred over western Nevada and moved southeast during the day, but a couple of these cases also occurred over central Utah, and one over the Snake River Plain of Idaho. It is important to note that the postfrontal environment of an intermountain cold front is usually cloudy, which blocks satellite detection of dust plumes. In an effort to avoid a bias towards southwest transport we computed backtrajectories for all KSLC dust events since 2004. Using the web version of the NOAA Hybrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory model (HYSPLIT, http://www.arl.noaa.gov/ready/hysplit4.html; http://www.arl.noaa.gov/ready/hysplit4.html), we computed 6 hr backtrajectories ending at 1000 m above KSLC using 40km Eta Data Assimilation System (EDAS) data. Previous studies have used lagrangian transport models to trace atmospheric aerosols back to their source (Haller et al., 2011; Gebhart et al., 2001), but they have employed different durations, ending heights, and used ensembles. The 25 KSLC backtrajectories computed since 2004 reveal the majority of dust 18 comes from the south-southwest and southwest (Fig. 23) making the starting locations found from GOES imagery a good proxy for the primary emission sources. Only the airmass convection event on July 26, 2006 and the arctic frontal passage on March 13, 2005 have backtrajectories starting north of KSLC. The airmass convection event did not have a visible dust plume, but the arctic front did have a diffuse area of dust show up over the Snake River Plain in Idaho and move south towards KSLC. Since this was a diffuse area and not a plume it was not recorded on the plume plot (Fig. 22). The rest of the events all point towards source regions identified by GOES imagery. 4. Conclusions Dust events at KSLC occurred throughout the historical record, with considerable interannual variability. The vast majority of these events have visibilities above dust storm or severe dust storm criteria and blowing dust is the most common observer comment. Dust events have a bimodal monthly distribution with a primary peak in the spring and a secondary peak in the fall. Climatological winds have a local maximum during the spring months as well, but are fairly consistent for the remainder of the year demonstrating that winds alone cannot explain the dust day monthly frequency. Annual and monthly dust flux calculations offer a different perspective than the frequency distributions, but results are very similar with the exception of a more dramatic local minimum during the summer in the monthly dust flux distribution. This difference is attributed to the shorter and less intense airmass convection events common during the summer. Winds were southerly and southwesterly at the onset of the majority of dust events and these directions also transported most of the dust. The timing of events was skewed heavily towards afternoon hours coinciding with the climatological diurnal cycle. 19 Using only events from 2001 – 2010, we categorized each event by the primary mechanism for dust emissions and transport. These categories were: (1) airmass convection, (2) cold fronts or baroclinic troughs, (3) upstream stationary fronts or baroclinic troughs, and (4) other mechanisms. Airmass convection events had weak upper and lower tropospheric synoptic forcing, were shortlived, and were initiated by outflow from nearby convection. Transient and stationary baroclinic troughs and cold fronts made up three quarters of recent dust events. They have much higher lower tropospheric winds than climatology, a nearby baroclinic zone with associated 850 hPa height trough, and primarily occur in the spring and fall, but stationary baroclinic trough or cold front events have weaker upper level support and frontogenetical flow than transient events. All baroclinic trough or cold front events reported dust within 3 h of frontal passage. There were only two other mechanism events that had synoptic patterns different from the typical baroclinic trough or cold front. All categories produce stong winds capable of emitting dust, but winds alone cannot explain the frequency of dust emission. Land surface factors, such as soil moisture and erobability, are also important, but are beyond the scope of this research. GOES dust retrieval data and HYSPLIT back trajectories indicate the ancient depositional environments (e.g., ancient lake beds) in southwest Utah and Western Nevada are the primary dust emission sources for the Intermountain West. Specifically Sevier Desert, Carson Sink, Escalente Desert, and the Milford Flat area are common emitters. These areas experience high agricultural and recreational use, which are dust disturbing practices that lead to increased dust emission. Mitigating crust disturbing practices in these areas will help decrease dust flux over the IMW, which will improve air quality and decrease dust loading in the mountain snowpack 20 5. Acknowledgments 6. References Belnap, J., R. L. Reynolds, M. C. Reheis, S. L. Phillips, F. E. Urban, and H. L. Goldstein, 2009: Sediment losses and gains across a gradient of livestock grazing and plant invasion in a cool, semi-arid grassland, Colorado Plateau, USA. Aeolian Research, 1, 27-43. Bisal, F. and J. Hsieh (1966) Influence of soil moisture on erodibility of soil by wind. Soil Sci., 102, 143–14. Brazel, A. J., 1989: Dust and climate in the American southwest. Paleoclimatology and Paleometeorology: Modern and Past Patterns of Global Atmospheric Transport, M. Leinen and M. Sarnthein, Eds., NASA ASI Series C, Vol. 282, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 65–96. Brazel, A. J., and W. G. Nickling, 1986: The relationship of weather types to dust storm generation in Arizona (1965-1980). Journal of Climate, 6, 255-275. Brazel, A. J., and W. G. Nickling, 1987: Dust storms and their relation to moisture in the Sonoran-Mojave desert region of the south-western United States. Journal of Environmental Management, 24, 279-291 Carlson, T. N., 1979: Atmospheric turbidity in Saharan dust outbreaks as determined by analyses of satellite brightness data. Mon. Wea. Rev., 107, 322–335. 21 Changery, M. J., 1983: A dust climatology of the western United States. Prepared for the Division of Health, Siting and Waste Management Office, Nuclear Regulatory Office. National Climatic Data Center, Ashville, NC, U.S.A. Draxler, R. R. and G. D. Rolph, 2011. HYSPLIT (HYbrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory) Model access via NOAA ARL READY Website (http://ready.arl.noaa.gov/HYSPLIT.php). NOAA Air Resources Laboratory, Silver Spring, MD. Fairlie, T. D., D. J. Jacob, and R. J. Park, 2007: The impact of transpacific transport of mineral dust in the United States. Atmospheric Environment, 41, 1251-1266 Federal Meteorological Handbook ,FMH, 2005 September. Surface Weather Observations and Reports. Retreived from: http://www.ofcm.gov/fmh-1/fmh1.htm Gebhart, K. A., S. M. Kreidenweis, and W. C. Malm, 2001: Back-trajectory analyses of fine particulate matter measured at Big Bend National Park in the historical database and the 1996 scoping study. The Science of the Total Environment, 276, 185-204 Gillette, D. A., 1999: A Qualitative geophysical explanation for hot spot dust emitting source regions. Contr. Atmos. Phys., 72, 67-77 Gillette, D. A., 1988: Threshold friction velocities for dust production for agricultural soils. Journal of Geophysical Research, 93, 12,645-12,662 Gillette, D. A., J. Adams, A. Endo, and D. Smith, 1980: Threshold velocities for input of soil particulates into the air by desert soils. Journal of Geophysical Research, 87, 9003-9016 Glickman, T. S., Ed., 2000: Glossary of Meteorology. 2d ed. American Meteorological Society, 855 p 22 Gorrell, M., 2011, Aug 22: Big Fourth of July weekend boosts Utah resorts. The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved from http://www.sltrib.com Goudie, A. S., and N. J. Middleton, 2001: Saharan dust storms: nature and consequences. EarthScience Reviews, 56, 197-204 Hall Jr., F. F., 1981: Visibility reductions from soil dust in the western U.S. Atmospheric Environment, 15, 1929-1933 Hallar, A. G., G. Chirokova, I. McCubbin, T. H. Painter, C. Wiedinmyer, and C. Dodson, 2011, Atmospheric bioaerosols transported via dust storms in the western United States. Geophys. Res. Lett., 38, L17801, doi:10.1029/2011GL048166. Hansen, J., and L. Nazarenko, 2004: Soot climate forcing via snow and ice albedos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 101, 423-428. Holcombe, T. L., T. Ley, and D. A. Gillette, 1997: Effects of prior precipitation and source area characteristics on threshold wind velocities for blowing dust episodes, Sonoran Desert 1948–78. Journal of Applied Meteorology, 36, 1160–1175 Husar, R. B., D. M. Tratt, B. A. Schichtel, S. R. Falke, F. Li, D. Jaffe, S. Gasso, T. Gill, N. S. Laulainen, F. Lu, M. C. Reheis, Y. Chun, D. Westphal, B. N. Holben, C. Gueymard, I. McKendry, N. Kuring, G. C. Feldman, C. McClain, R. J. Frouin, J. Merrill, D. DuBois, F. Vignola, T. Murayama, S. Nickovic, W. E. Wilson, K. Sassen, N. Sugimoto, and W. C. Malm, 2001: Asian dust events of April 1998. Journal of Geophysical Research, 106, 18317–1833 Jaffe, D., T. Anderson, D. Covert, R. Kotchenruther, B. Trost, J. Danielson, W. Simpson, T. Berntsen, S. Karlsdottir, D. Blake, J. Harris, G. Carmichael, and I. Uno, 1999: Transport of Asian air pollution to North America. Geophys. Res. Lett., 26, 711–714. 23 Jauregui, E., 1989: The dust storms of Mexico City. International Journal of Climatology, 9, 169-180. Jeglum, M. E., W. J. Steenburgh, T. P. Lee, L. F. Bosart, 2010: Multi-Reanalysis Climatology of Intermountain Cyclones. Mon. Wea. Rev., 138, 4035–4053. Mbourou, G. N’Tchayi, J. J. Bertrand, and S. E. Nicholson, 1997: The diurnal and seasonal cycles of wind-borne dust over Africa north of the equator. J. Appl. Meteor., 36, 868– 882. Mc Kenna-Neuman C. and Nickling W.G., 1989: A theoretical and wind tunnel investigation of the effect of capillary water on the entrainment of sediment by wind. Canadian Journal of Soil Science. Vol 69, 79-96 Mesinger, F., and Coauthors, 2006: North American Regional Reanalysis. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 87, 343–360 NCDC, 2001: http://www1.ncdc.noaa.gov/pub/data/inventories/ish-tech-report.pdf NCDC, 2008: Data documentation for data set 3505 (DSI-3505) Integrated Surface Data. [Available from http://www1.ncdc.noaa.gov/pub/data/documentlibrary/tddoc/td3505.pdf]. Neff, J. C., A. P. Ballantyne, G. L. Farmer, N. M. Mahowald, J. L. Conroy, C. C. Landry, J. T. Overpeck, T. H. Painter, C. R. Lawrence, and R. L. Reynolds, 2008: Increasing eolian dust deposition in the western United States linked to human activity. Nature Geosci., 1, 189-195. Nicholson, S., 2000: Land surface processes and Sahel climate. Rev. Geophys., 38, 117–139 Nickling, W. G. and A. J. Brazel, 1984: Temperol and spatial characteristics of Arizona dust storms (1965-1980). Journal of Climatology, 4, 645-660. 24 Painter, T. H., J. S. Deems, J. Belnap, A. F. Hamlet, C. C. Landry, and B. Udall, 2010: Response of Colorado River runoff to dust radiative forcing in snow. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 107, 17125-17130 Painter, T. H., A. P. Barrett, C. C. Landry, J. C. Neff, M. P. Cassidy, C. R. Lawrence, K. E. McBride, and G. Lang Farmer, 2007: Impact of disturbed desert soils on duration of mountain snow cover. Geophys. Res. Lett., 34, L12502, doi:10.1029/2007GL030284. Pope, C. A., D. V. Bates, and M. E. Raizenne, 1995: Health effects of particulate air pollution: time for reassessment? Env. Health Perspect., 103, 472–480 Prospero, J. M., and P. J. Lamb, 2003: African droughts and dust transport to the Caribbean: climate change implications. Science, 302, 1024-1027 Qian, W., L. Quan, and S. Shi, 2002: Variations of the dust storm in china and its climatic control. J. Climate, 15, 1216–1229 Orgill, M. M., and G. A. Sehmel, 1976: Frequency and diurnal variation of dust storms in the contiguous U.S.A., Atmospheric Environment, 10, 813-825 Ramanathan, V., P. J. Crutzen, J. T. Kiehl, and D. Rosenfeld, 2001: Aerosols, climate, and the hydrological cycle. Science, 294, 2119–2124 Ritchie, E. A., K. M. Wood, D. S. Gutzler, and S. R. White, 2011: The influence of Eastern Pacific tropical cyclone remnants on the Southwestern United States. Mon. Wea. Rev., 139, 192-210. Rolph, G.D., 2011. Real-time Environmental Applications and Display sYstem (READY). Website (http://ready.arl.noaa.gov). NOAA Air Resources Laboratory, Silver Spring, MD. 25 Saleh, A. and Fryrear, D.W. (1995) Threshold wind velocities of wet soils as affected by wind blown sand. Soil Sci., 160, 304–309 Salt Lake City Department of Public Utilities, 1999: Salt Lake City Watershed Management Plan. Bear West Consulting Team, 129 pp. [Available from www.slcgov.com/utilities/PDF%20Files/slcwatershedmgtplan.pdf]. Shao, Y., and J. Wang, 2003: A climatology of Northeast Asian dust events. Meteor. Zeitschrift, 12, 187-196. Shao, Y., Y. Yang, J. Wang, Z. Song, L. M. Leslie, C. Dong, Z. Zhang, Z. Lin, Y. Kanai, S. Yabuki, and Y. Chun, 2003: Northeast Asian dust storms: Real-time numerical prediction and validation. Journal of Geophysical Research, 108, D22, 4691. Shafer, J. C., and W. J. Steenburgh, 2008: Climatology of strong intermountain cold fronts. Mon. Wea. Rev., 136, 784-807 Song, Z., J. Wang, and S. Wang, 2007: Quantitative classification of northeast Asian dust events. Journal of Geophysical Research, 112, D04211. Steenburgh, W. J., and T. I. Alcott, 2009: Secrets of the "Greatest Snow on Earth". Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 89, 1285-1293. Stout, J. E., 2001: Dust and environment in the Southern High Plains of North America. Journal of Arid Environments, 47, 425-441 Swap, R., S. Ulanski, M. Cobbett, and M. Garstang, 1996: Temporal and spatial characteristics of Saharan dust outbreaks. Journal of Geophysical Research, 101, 4205–4220 Tanaka, T. Y., and M. Chiba, 2006: A numerical study of the contributions of dust source regions to the global dust budget. Glob. Planet. Change, 52, 88-104. 26 Wheaton, E. E. and A. K. Chakravarti, 1990: Dust storms in the Canadian prairies. International Journal of Climatology, 10, 829-837. WMO, 2009: Manual on Codes. See WMO (2009b) in my directory. We'll need to do full reference eventually. Yasunori, K., and M. Masao, 2002: Seasonal and regional characteristics of dust event in the Taklimakan Desert. Journal of Arid Land Studies, 11, 245-252 Zhoa, T., S. Ackerman, and W. Guo, 2010: Dust and smoke detection for multi-channel imagers. Remote Sensing, 2, 2347-2368 Zobeck, T. M., D. W. Fryrear, and R. D. Pettit, 1989: Management effects on wind-eroded sediment and plant nutrients. J. Soil Water Cons., 44, 160–163 27 Table 1: DS-3505 dust-related present-weather categories, including full and abbreviated (i.e., used in the text) descriptions and the number of total and used reports at Salt Lake City. Category Full Description Abbreviated Description Reports 06 Widespread dust in suspension in the air, not raised by wind at or near Dust in suspension 178 (155) Blowing dust 905 (867) Dust whirl(s) 1 (0) Duststorm 2(1) Duststorm 1 (0) Duststorm 1 (0) Duststorm 1 (0) the station at the time of observation 07 Dust or sand raised by wind at or near the station at the time of observation, but no well-developed dust whirl(s) or sand whirl(s), and no duststorm or sandstorm seen 08 Well developed dust whirl(s) or sand whirl(s) seen at or near the station during the preceding hour or at the time of observation, but no duststorm or sandstorm 09 Duststorm or sandstorm within sight at the time of observation, or at the station during the preceding hour 30 Slight or moderate duststorm or sandstorm has decreased during the preceding hour 31 Slight or moderate duststorm or sandstorm no appreciable change during the preceding hour 32 Slight or moderate duststorm or sandstorm has begun or has increased during the preceding hour 33 Severe duststorm or sandstorm has decreased during the preceding hour Duststorm 0 (0) 34 Severe duststorm or sandstorm no appreciable change during the Duststorm 0 (0) Duststorm 0 (0) preceding hour 35 Severe duststorm or sandstorm has begun or has increased during the preceding hour 28 98 Thunderstorm combined with duststorm or sandstorm at time of Duststorm observation, thunderstorm at time of observation Table 2 Date Airmass Stationary baroclinic Convection trough or cold front Baroclinic trough or cold front Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal 3/23/2002 4/15/2002 6/1/2002 X 9/16/2002 X 2/1/2003 4/1/2003 X 4/2/2003 9/16/2003 4/28/2004 5/10/2004 29 Other Synoptic Patterns X X X X X X X X 2 (0) 7/9/2004 Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal X 10/17/2004 X 3/13/2005 4/13/2005 5/16/2005 7/22/2005 X 7/30/2005 X 5/19/2006 X 7/19/2006 X 7/26/2006 X 4/29/2008 5/20/2008 7/27/2008 X 8/31/2008 3/4/2009 3/21/2009 X 30 X X X X X X X X 6/30/2009 X 8/5/2009 X Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal Postfrontal Prefrontal Frontal 8/6/2009 8/30/2009 X 9/30/2009 3/30/2010 X X X X X X X X 4/27/2010 Postfrontal Figure Captions Fig. 1: Topography and geography of the study region. Fig. 2: Examples of dust layering in the late-season Wasatch Mountain snowpack. (a) Ben Lomond Peak (XXXX m), April 2005. (b) Alta 2009, (b) Alta 2010. Fig. 3: Annual number of dust events reported at KSLC (1930 – 2010 water year) Fig. 4: Histogram of minimum reported visibility (km) of each dust event. Fig. 5: Histogram of annual near surface dust flux (g m-2) at KSLC 31 Fig. 6: Number of dust events by month Fig. 7: Histogram of monthly near surface dust flux (g m-2) at KSLC Fig. 8: Histogram of monthly KSLC observations above our arbitrary threshold velocity of 10 m s-1 Fig. 9: Number of dust events by hour (MST) Fig. 10: Histogram of hourly (MST) KSLC observations above our arbitrary threshold velocity of 10 m s-1 Fig. 11: Wind Rose of initial surface wind directions for each dust event broken down by wind speed (m s-1) Fig. 12: Directional frequency (%) of near surface dust flux Fig. 13: Number of dust events by month for recent dust events (2001 – 2010 water year) Fig. 14: Analysis of the 19 May 2006 mesoscale convective event at 16 MST. (a) NEXRAD .5 degree tilt radar reflectivityat 16:05 MST, (b) NARR dynamic tropopause (2 PVU) pressure (shaded every 50 hPa), dynamic tropopause wind barbs [full (half) barbs denote 5 (2.5) m s-1], 32 and isotachs (contoured every 15 m s-1). (c) 700 hPa temperature (every 2 C) and wind barbs ([as in (a)]. (d) 850 hPa geopotential heights (every 40 m) and wind barbs [as in (a)]. Fig. 15: Number of dust reports relative to approximate time of frontal passage Fig. 16: Analysis of the 10 May 2004 baroclinic trough or cold front event at 17 MST. (a) Visible satellite image with dust highlighted in red. (b) – (d) same as in Fig. 14 Fig. 17: (a) Frequency of 700 hPa wind speed (m s-1), (b) direction, and (c) height of the planetary boundary layer (m) for airmass convection events and [(d)-(f)] baroclinic trough or cold front events (solid black line) compared to the NARR climatological values (dashed gray line). Fig. 18: Same as Fig. 16 but for stationary baroclinic trough or cold front event on 10 MST 1 Apr 2003 Fig. 19: Plot of plume origin (black cross) and orientation for KSLC (blue line), Delta (orange line), Elko (cyan line), and Pocatello (magenta) dust events, dust events reported at multiple stations (red), and dust events from personal notes (purple). 1 km Terrain (m) shaded. Fig. 20: HYSPLIT 6 h backtrajectories for each KSLC dust event since 2004 ending 1000 m above KSLC 33