Mbokodweni Estuary

advertisement

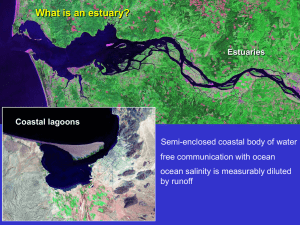

eThekwini Sanitation Master Plan - Inception Report Draft Discussion Document 1: September 2014 Overview eThekwini has a clear vision for its future development. This is provided in the IDP read in conjunction with the approved Spatial Development Framework (SDF) (see Annexure 1). Based on the SDF and the associated Spatial Development Plans, eThekwini Water & Sanitation (EWS) has calculated the “ultimate” wastewater flows in each of its catchment. These flows will be treated by existing or future wastewater treatment works (WWTWs). The WWTWs are shown diagrammatically on Figure 1 of Annexure 2, which gives their locations in relation to the catchments and effluent discharge points on the rivers. Figures 2 and 3 of Annexure 2 give the flow information for each WWTW as Megalitres per day, in the format “Current Flow / Current Capacity / Future Flow”. These treated effluent discharges, apart from the Southern and Central WWTWs, end up in the estuaries along the coast. Most of eThekwini’s water supply comes from the uMngeni River system. But because of the geography of the city, the majority of the WWTWs are situated in catchments of rivers other than the uMngeni. As a result, the rivers and estuaries downstream of these WWTWs receive additional anthropogenic inflows, in excess of their “natural” river flows. These additional inflows have environmental impacts on the estuarine environments, and are subject to regulation through both water and environmental legislation. To mitigate the effect of the wastewater flows on the sensitive estuaries, it is necessary to analyse adjacent estuaries as part of a system, with existing or potential interrelationships between the catchments, including inter-catchment transfers. Because the estuaries of the central rivers in the city are relatively insensitive to effluent discharges, it is possible to analyse the sensitive estuaries in two separate systems – north and south. The reasons for the central estuaries being insensitive to effluent discharges are: uMngeni – this is a water starved estuary, since water from the river system is treated and transferred to a number of other catchments. Umbilo – the river discharges into Durban Bay which is a heavily degraded estuary, insensitive to additional flows. uMhlatuzana – the river discharges into Durban Bay. uMlaza – river enters the ocean through the Umlaas Canal, and the estuarine ecological system no longer exists. In each system there are several options for mitigating the effects on the estuaries – Annexure 2, Figures 4 and 5. This report examines the estuary impacts, and suggests various mitigation options for each system (north and south). Background The prioritisation of development areas and initiatives to ensure that the Municipality expands in a sustainable manner from its current level of development to the future vision as depicted in the SDF, are being unpacked as part of the Built Environment Performance Plan (BEPP), which, in turn, will inform the application for the next set of grant funding under the Integrated Cities Development Grant (ICDG). The development / expansion of new / existing wastewater treatment works, and, inter alia, the associated means of disposal of treated effluent, is a critical input to the BEPP. The volumes, and quality, of treated sewage effluent which may be discharged to river and estuary are determined under the Dept Water and Sanitation’s (DWS) “classification” process. The objective of the “classification” process is to achieve a balance between the ecological impacts to the water resource with the social and economic impacts of developing the catchment. Social impacts will include meeting the housing backlog etc., and the economic impacts will include development which results in an increase in the rates base, providing new jobs etc. The economic impact will also include the cost of engineering infrastructure deemed necessary to divert treated effluent away from being discharged to the water resource, and the financial benefits from tourism of a clean, safe holiday environment. Over-arching Issues. Overlapping mandates The Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) also has an overlapping mandate for the control of discharges to estuaries. It is not clear how the two National Departments will interact particularly as certain parts of the respective “policies” appear to be at variance with one another. This has been identified in discussions conducted under the auspices of National Treasury as an issue that needs to be taken forward, jointly by DWS and DEA, as a matter of urgency. Balancing the impacts The DWS “classification” process requires that a balance be achieved between ecological, social and economic impacts (refer to ‘Background’ above). Classification within the context of an urban developed – and developing – area has not been undertaken previously by DWS and the format to unpack and determine this “balance” has yet to be finalised within DWS. The most that has been proposed is that a ‘multi-criteria’ matrix be developed, and weighting applied to the various elements of that matrix, but how it will work out in reality has yet to be developed beyond concept level by the specialist consultants and DWS. eThekwini has made representations to DWS that eThekwini, as an equal partner in government, must be consulted before any decision regarding ‘classification’ of eThekwini water resources is made. The acting DG of DWS has confirmed that this will take place in line with the mandate for cooperative governance between National, Provincial and Local government, and has further undertaken to amend the composition of the DWS project team if this is deemed necessary. Page 2 Infrastructure mitigation measures are being examined under a separate commission by eThekwini in order to gain a better understanding of their cost and feasibility. With the exception of a new sea outfall (or outfalls) all such measures will rely on pumping large volumes of treated effluent. This kind of mitigation measure is far from ideal as, not only will such schemes be totally reliant upon a consistent electricity supply (which, it seems, cannot be guaranteed in the short to medium term) but eThekwini is also suffering from a significant rise in theft of metal / cables etc. throughout the municipal area, which, if it continues apace, will result in schemes which are dependent upon a power supply, being out of commission for long periods. The capital cost of any infrastructure mitigation measure is likely to exceed the capacity of eThekwini to fund such work. DWS acknowledge this and is involving National Treasury in these ongoing engagements with a view to National Treasury providing additional grant funding. A mitigation measure which is particularly attractive is the re-cycling of treated effluent for re-use. Investigations have previously concluded that there is no realistic opportunity to re-cycle and re-use to a ‘2nd class water standard’, for use in industry. Re-use to a potable water standard is a technically viable opportunity but, when previously proposed by eThekwini, was met by strong resistance from a small, but very vocal group who protested largely on religious grounds. At present the eThekwini Council will not give authorisation to take potable re-use forward in any manner and it will take an extra- ordinary intervention from DWS to persuade the Council to re-consider this, at least for the next couple of years. Ecological reserve determinations There is a view among several estuarine specialists that the premise behind the structure of the estuarine ecological reserve (i.e. that of measuring the existing and future conditions against the ‘natural’, (i.e. pre any development) state of the estuary, and seeking to regain those natural conditions as far as possible, is not the correct approach, particularly for estuaries within highly developed urban areas. Rather a more holistic view of the environment should be taken, and that the reserve methodology needs to be revisited for such urban areas. The ecological reserve studies within eThekwini conducted to date have been limited to estuarine studies. This has been done on the premise that an estuary is the main ecological driver, and hence the river will respond favourably to any changes made for the benefit of the estuary. The ecological reserve studies conducted to date have not included any consideration of nutrients present in treated effluent. Certain of the reserve studies, where this is seen as an important factor, will need to be reviewed. In accordance with the table attached as Annexure 3, the affected WWTWs could reasonably reduce nutrients to level 2 (Total N = 3 mg/l : P = 1 mg/l). eThekwini estuaries There are 16 estuaries within eThekwini of which 8 are impacted by existing and / or future discharges of treated effluent. Of these, the anthropogenic impacts on the UMkhomazi, uMlaza, Durban Bay uMngeni systems far outweigh any impact from the current or future discharge of treated effluent. The focus of this section of the ‘sanitation master plan’, will thus be on the Wastewater treatment works in the catchments of the 5 remaining estuaries Page 3 Viz. Little aManzimtoti, Mbokodweni, Mhlanga, uMdloti and uThongati These rivers / estuaries, and the treatment works in the respective catchments, are shown on the diagram in Figure 1. There is no realistic connection between infrastructure mitigation measures which may be considered for the two estuaries in the south (Little aManzimtoti, Mbokodweni) and the three estuaries in the north. However, in addition to each estuary being considered individually, each of the two groupings of estuaries needs to be considered as a collective. Water Use Licenses eThekwini advertised a contract to prepare all outstanding Water Use license applications. However, due to a supply chain management procurement problem any award is now likely to be delayed until early 2015. DWS are promoting a two pronged strategy with respect to the issue of WWTWs water use licenses. Prong 1 The licenses and approvals which are required in order to release development in the ‘EWS pressure areas’ would be part of a ‘quick interim solution’ whereby the issue of all necessary licences, approvals etc. would be undertaken without the ‘normal approval processes’ being followed. It is being anticipated, we understand, that this ‘short term strategy’ would be concluded within the next 6 months,(i.e. by Jan / Feb 2015) with all licenses being issued within that period. Prong 2 The remainder of the licenses, (for the ultimate capacity of the Works) would then be included as part of a larger regulatory process which is still to be developed by DWS and would possibly use eThekwini as a pilot. This may have a timeline of up to 5 years. In order to take this proposal - of working towards some form of interim licensing – forward, a spreadsheet of the various eThekwini wastewater treatment works, identified per catchment, and giving current capacity, current flow and the ultimate projected flows (column H) is included as Annexure 4. In addition the draft PES, REC/BAS and UWS are quoted for future reference. The additional flow, over and above that determined from the SDF, allows for further expansion of a reticulated waterborne sewerage scheme further into what are currently defined as rural areas (and hence currently assumed as dry sanitation). The capacity of each Works would be increased on an incremental basis in line with the increases in flow to the Works. Thus the Works where the development pressures are greatest, and the short term interim licensing requirements to allow the next phase development of these Works, are shown in column F. In summary (this is the sum of the existing capacity and the first phase of the required expansion) Tongaat Works = 20 Ml/day Page 4 uMdloti Works = 25 Ml/day (new regional works) Phoenix Works = 50 Ml/day Amanzimtoti Works = 45 Ml/day Isipingo Works = 25 Ml/day Kingsburgh Works = 20 Ml/day uMkhomazi Works = 10 Ml/day (new regional works) Figure 2 shows the ultimate Works capacity, and Figure 3 shows the interim licensing requirements. uThongati Estuary General This is a moderate importance estuary which forms the boundary between eThekwini and Ilembe municipalities. As such the estuary receives effluent flows from both the eThekwini and the Ilembe (Frasers) WWTWs. The flow requirements from Ilembe need to be added to the current and ultimate eThekwini wastewater flows. (Figure 4) Being the boundary between 2 Municipalities the estuary management plan is a Provincial responsibility. The summary report for the Tongaat estuary (a combined report with the uMdloti estuary) is attached as Annexure 5 Water Use License for initial expansion of Works The reserve determination (Annexure 5, page 16, fig 2) identified that a flow of some 30 Ml/day plus over and above the then present day flow (of 13 Ml/day max) [= 43 Ml/day] would provide an identifiable improvement to the EHI index score over present state and at least retain the estuary in its existing D category. If the illegal causeway was to be removed the figure of 43 Ml/day could well increase. (or, at a total flow of 43 Ml/day, the estuary may creep into a category C) As previously advised the immediate expansion for the eThekwini Tongaat Works would be to 20 Ml/day (total capacity), and assuming Fraser Works (Ilembe) will increase from 5 to 8 Ml/day over the same period, then the flow to the estuary in the short term (5 to 10 years) will be some 28 Ml/day. There thus appears to be plenty of scope for eThekwini to be issued with an immediate License for a 20 Ml/day Works as required. The only issue which then remains to be factored into the above is the effect of the added nutrients which were not considered in the original Reserve study. In accordance with the table in Annexure 2, both Ilembe and eThekwini, could reasonably (it is assumed) reduce nutrients to level 2 (Total N = 3 mg/l : P = 1 mg/l). Page 5 The upstream boundary of the estuary is adjudged, in the Reserve report, to be some 7 km upstream of the mouth and hence the discharge from the Tongaat WWTWs falls on the boundary of the delineated estuary zone. Hence, as the respective mandates currently exist, it will be necessary to obtain agreement from DEA to the above. Based on all the above, and the proposal from DWS of an ‘interim WULA ‘ approval for the first phase expansion of key WWTWs , and bearing in mind the delay being experienced by eThekwini in commencing the formal WULA application for this Works, a revised, simplified WULA application is needed. The proposal is for a task team to work through the above licensing issues. This will allow for : Agreement on the extent that the existing ecological estuarine reserves all need to be revisited (updating with new data / consideration of nutrients etc.) Agreement on the way forward for the issue – within 6 months – of Water Use Licenses for the initial expansion phase for various WWTWs (or, for the new uMdloti regional Works, the first phase of the new Works) Establishing mechanisms with DEA for the issue of their Coastal Discharge permits Water Use License for Ultimate Works Capacity The suggested way forward is : i) DWS to implement all the recommendations from the current reserve study which are not flow related including the removal of the causeway and the implementation of continuous monitoring of total inflows to the estuary; water level changes ; mouth state observations and water quality ii) The EC / PES of the estuaries to the north of Tongaat need to be identified so that these estuaries can be included in the consideration of possible trade-offs. iii) DWS initiates the inclusion of Ilembe in the development of solutions for the estuary. iv) Due to the catchment being a key National growth area (and hence that the option of limiting development in any way is probably not feasible) that DWA determine the parameters required to be considered to develop a best case trade-off condition which would compensate for the uThongati estuary to reduce to an E EC uMdloti Estuary General This is a moderate importance estuary and is considered as a special case with both DWS (Hazelmere dam) and eThekwini contributing to the deterioration in the ecology of the estuary and both organisations need to be actively involved in finding the best way forward. The uMdloti estuary is currently impacted on by the abstraction from Hazelmere dam (and the proposed raising of that dam), the dam release policy, and will be impacted on in the future by the significant increase in wastewater flow as a result of development in the catchment. There are some challenges around the site for the new regional WWTWs which are being resolved. Page 6 Water Use Licenses It has previously been agreed that DWS would arrange a workshop/study to determine the “practical” BAS within the reality of the constraints imposed by the increased abstraction from the raised dam, the environmental release flows from the dam, the possible future implementation of a ‘reserve ‘flow from the Tugela, the increased effluent volumes from this National key growth area and the opportunity of improved effluent quality standards. The anticipation is that the best ‘balanced’ combination of the above will be considered as a “preliminary classification” for input into the ‘classification’ process. eThekwini, DWA and stakeholders also need to agree on the role of the estuary as the current water body (which provides sought after passive and active recreational opportunities) will ‘disappear’ if frequency of mouth opening is significantly increased. A proposed agenda for the workshop has been discussed with DWS (Ms B. Weston) and is attached as Annexure 6. Water Use License for initial expansion of Works The existing abstraction from Hazelmere dam, and the increased abstraction from a raised dam, are the main drivers in the degradation of the system. The reserve only tested an increase in discharge from the WWTWs of 30 Ml/day, which indicated a slight improvement in estuarine health. The report (page 15 of Annexure 5) notes that “higher volumes of wastewater of appropriate quality could be used to raise the category to a C but this was not tested during the reserve workshop”. The added scenarios do now need to be tested in conjunction with the addition of nutrients (not previously tested). But as the proposed first phase of the Works is to be 25 Ml/day there does appear to be scope for an initial license. Mhlanga Estuary General The estuary should be on an improving ecological trajectory towards achieving B (BAS) following the diversion of the effluent flow from Phoenix Works away from the Mhlanga river into the Mhlangane river, and hence to the uMngeni river. However, the diversion scheme has not functioned at all for the last 9 months (plus), (and only intermittently for various reasons prior to that) due to the theft of the cabling to the pump station. The exact details of the commissioning problems and the events thereafter are currently being documented. There is a current WUL which allows Phoenix Works to accept increased flow up to 38,5 Ml/day, current flow to the Works being 20 Ml/day (with the WWTWs being currently expanded to 50 Ml/day capacity). The Cornubia development is in the catchment of these WWTWs, which will increase the flow substantially in the short term, but, notwithstanding this there are no development hold-ups in this catchment foreseeable in the next 5 to 7 years. Water Use License for Ultimate Works Capacity Consultants Marine and Estuarine Research (MER) have previously pointed out that there are corrections to the ecological reserve study conducted in circa 2000 (check date ), which need to be addressed. Page 7 A suggested way forward is : i) DWA to implement continuous monitoring of total inflows to the estuary; water level changes ; mouth state observations and water quality to allow an updated med/high level confidence reserve study within 12 months ii) DWA to conduct a med/high confidence ecological reserve study using the current methodology iii) DWA to review and implement the recommendations of the current reserve study which are not flow related Mbokodweni Estuary General This is an estuary of low importance situated within a catchment where there are pressures for (mainly Housing) development which is seen as an essential social intervention for eThekwini. The estuarine reserve report provided three recommendations to achieve the REC which can be taken forward in the following manner. i) Rehabilitation of the mouth area. DWS to identify extent of work which would be necessary to significantly improve the PES, and EWS to provide costs ii) Improve quality. DWS to identify quality standards for effluent which would be necessary to significantly improve the PES, and EWS to provide costs iii) Best case trade off conditions be developed by DWS Little aManzimtoti Estuary General This is an estuary of low importance situated within a catchment where there are high level pressures for development which is seen as key to the economic development of eThekwini. Toyota (and other developers) have previously submitted development proposals for this catchment which the Council considered as very important. However, development proposals of this nature cannot be addressed as the WWTW (Kingsburgh Works) has minimal spare (uncommitted) capacity. A suggested way forward is to consider further the three recommendations to achieve the REC i) Reduction in flow from the WWTW: This is not an option unless the key economic development is abandoned, or infrastructure mitigation measures are constructed.(see section below) ii) Improve water quality in the estuary: DWA to identify quality standards for effluent which would be necessary to significantly improve the PES, and EWS to provide feasibility / costs ii) Rehabilitation of the flood plain: This requirement needs to be unpacked by DWA/EWS and then costed The best case trade-off conditions be developed. Other estuaries not materially affected by the discharge of treated effluent : For completeness the following comments are made with respect to the following estuaries which will be affected by the discharge of treated effluent. Page 8 uMngeni The intended releases from Inanda dam are recorded as achieving the REC provided that wastewater flows are restricted to the ultimate projected flows from Northern, Kwa Mashu and Phoenix WWTWs only, all at general treatment standards. Hence, no action required under this study or until additional flows discharging to the uMngeni are proposed. Durban Bay In-flow of treated sewage effluent to the harbour not considered to be a major influence of EC of the harbour compared to effects of uncontrolled storm water and other engineering/infrastructure impacts Suggested way forward DWA to investigate removal of nutrients from the treated effluent discharging to the harbour by modelling, but to be implemented only if storm water quality can be improved and costs at WWTWs are warranted uMkhomazi Estuary It is understood that the uMkhomazi estuary will be evaluated later in the classification study at a med/high confidence level. It is foreseen that the REC could be achieved by i) Removal of temporary weir ii) Rehabilitate and manage the floodplain iii) Restore/maintain base flows It is confirmed that the proposed WWTW will be designed to achieve the general standards for discharge. There are ongoing discussions regarding an EIA application and a WULA, for the proposed new regional WWTWs (ultimate capacity 20 Ml/day). Infrastructure Mitigation Measures – northern estuaries The following studies are under way with a view to test the feasibility and cost of possible infrastructure mitigation measures: These are shown in diagrammatic form in Annexure 2 Figure 4 and consist of: Marine Outfall i) Option for only Tongaat catchment or Tongaat plus uMdloti catchments ii) Options for siting of treatment works / marine outfall uThongati catchment i) Potable water re-use plant for Tongaat catchment (including pump station, pipeline dia / routes to Northern aqueduct) ii) Pump flow to Hazelmere dam (including pump station, pipeline dia / routes) iii) Pump flow back to uMngeni river uMdloti catchment i) Pump flow to Hazelmere dam (including pump station, pipeline dia / routes) Page 9 ii) Potable water re-use plant for uMdloti catchment (including pump station, pipeline dia/ routes to Northern aqueduct) iii) Pump flow back to uMngeni river Hazelmere dam Determine maximum return flow pumped volume as limited by salts build up. Umhlanga Catchment i) Pump flows to Umgeni catchment (based on capex / opex of existing pumping scheme Phoenix Works to uMngeni river) ii) Pump flow in excess of capacity of existing pumping diversion scheme to Hazelmere dam iii) Potable water re-use plant at Phoenix Works Infrastructure Mitigation Measures – southern estuaries Possible mitigation measures are shown in diagrammatic form in Annexure 2 Figure 5 and consist of: New sea outfall off Amanzimtoti Not seen to be likely at this stage Mbokodweni catchment i) Pump flow northwards to Isipingo lagoon ii) Pump flow northwards to dig-out-port iii) Pump flow northwards to Umlaas canal iv) Accept Mbokodweni as a ‘trade-off ‘ estuary (and pump flows from Little aManzimtoti to Mbokodweni and discharge combined flow to Mbokodweni estuary) Little aManzimtoti Catchment i) Pump flow northwards to combine with Mbokodweni flows and dispose as options for Mbokodweni as above ii) Pump flow southwards to uMkhomazi estuary iii) Accept Little aManzimtoti as a ‘trade-off’ estuary and pump flows from Mbokodweni to Little aManzimtoti and discharge combined flow to Little aManzimtoti estuary. Page 10