CSKE PBL Learning Guide

advertisement

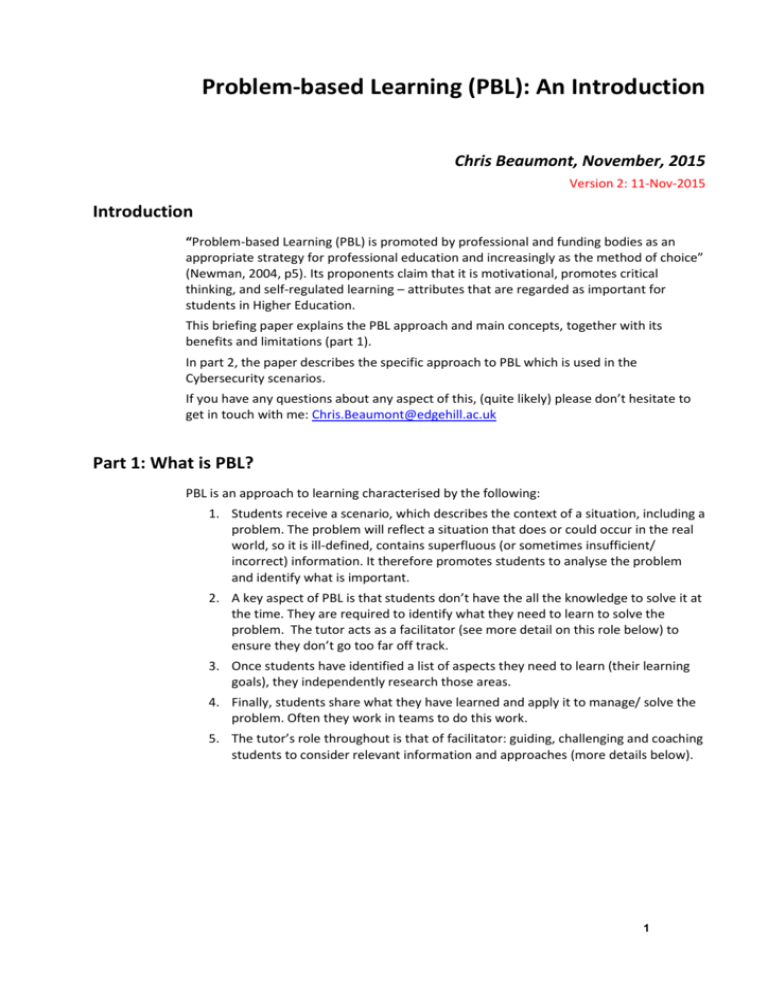

Problem-based Learning (PBL): An Introduction Chris Beaumont, November, 2015 Version 2: 11-Nov-2015 Introduction “Problem-based Learning (PBL) is promoted by professional and funding bodies as an appropriate strategy for professional education and increasingly as the method of choice” (Newman, 2004, p5). Its proponents claim that it is motivational, promotes critical thinking, and self-regulated learning – attributes that are regarded as important for students in Higher Education. This briefing paper explains the PBL approach and main concepts, together with its benefits and limitations (part 1). In part 2, the paper describes the specific approach to PBL which is used in the Cybersecurity scenarios. If you have any questions about any aspect of this, (quite likely) please don’t hesitate to get in touch with me: Chris.Beaumont@edgehill.ac.uk Part 1: What is PBL? PBL is an approach to learning characterised by the following: 1. Students receive a scenario, which describes the context of a situation, including a problem. The problem will reflect a situation that does or could occur in the real world, so it is ill-defined, contains superfluous (or sometimes insufficient/ incorrect) information. It therefore promotes students to analyse the problem and identify what is important. 2. A key aspect of PBL is that students don’t have the all the knowledge to solve it at the time. They are required to identify what they need to learn to solve the problem. The tutor acts as a facilitator (see more detail on this role below) to ensure they don’t go too far off track. 3. Once students have identified a list of aspects they need to learn (their learning goals), they independently research those areas. 4. Finally, students share what they have learned and apply it to manage/ solve the problem. Often they work in teams to do this work. 5. The tutor’s role throughout is that of facilitator: guiding, challenging and coaching students to consider relevant information and approaches (more details below). 1 Why PBL? Whilst PBL predates Social Constructivist learning ideas, it is aligned with those principles. In PBL, students identify what they need to learn, thus it does not depend on assumptions by the tutor – indeed in classes I have run, some students start with much more basic learning goals than others. This ensures that the learning is relevant to each individual – it starts from students’ current knowledge base. Knowledge is constructed by learners based on their experiences (reading, discussing, and practical work) rather than merely by acquiring external objective facts presented by a tutor. They must apply criticality to determine if the knowledge is relevant to the problem, of sufficient detail and then apply it in a real-world context. Furthermore it reflects aspects of professional practice. It develops transferable skills: problem-solving, selecting/evaluating information, communication, team-working. It can also be motivational – learning for a clear purpose – and helps retention. In short, students are actively seeking new information, integrating it with what is already known, organizing it in a meaningful way, and having a chance to explain it to others. Consequences for teaching This approach has very significant consequences for teaching. It requires a reorientation of the philosophy of teaching, changing to a facilitative approach rather than directive, giving power to students. Students learn through interaction with others and they are required to take more ownership and responsibility for learning. The learning process focuses on primary concepts, not isolated facts. Furthermore, students need to see the meaning of their new knowledge in the context of a problem, which is usually messy. This puts a significant burden on both students and tutors: students often feel overwhelmed at first and find the process stressful. Tutors often find it difficult to let go, and are concerned that students ‘aren’t learning enough’. Working in teams is both helpful and creates difficulties: Collaboration enables students to discuss and support each other to manage complex scenarios, yet it is always open to the classic group work problem of ‘freeloading’. Various recipes for PBL exist: some require a set of 7 steps, and such models assist students with a structured form of problem solving. For example, Woods (1995: pA-18) recommends a 3-phase approach: Phase 1 1. 2. 3. 4. Explore the problems, create hypotheses, and identify issues. Elaborate. Identify what you know already which is pertinent. Identify what you need to know. Prioritise learning issues, set learning goals and objectives and allocate resources. Members identify which tasks they will do. Phase 2 5. Individual self-study and preparation. Phase 3 6. Return to group, share new knowledge effectively so that all the group learn the information. Apply the knowledge to solve the problem. 7. Reflect on effectiveness of solution and process used. However, it is important to adapt the approach to suit the context in which is used: “It is rarely possible to translate a given approach from one context to another without considerable modification” (Boud & Feletti, 1997: 11). 2 “PBL is not a tool, it is a philosophy. It should not conflict with the learning environment. Thus, workloads and timetables must be consistent; the physical environment must be consistent” – Derek Raine (Uden & Beaumont, 2006: 292) “Be sure that you are not adding to the list of errors from using the method as the only method. True teaching must involve a cross section of educational technologies” - Peter French (personal communication). Facilitation Whilst there has been considerable dispute over the level of subject knowledge needed by facilitators, we consider that it is important for the facilitator to have specialist subject knowledge, since this makes for better monitoring of progress by students, though the knowledge can bring with it the temptation to teach. Bessant et al (ND: 3) identify the following key tasks for the facilitator: 1. Facilitate the group process and the PBL learning environment 2. Monitor, evaluate and guide student discussions 3. Have background information about the topic in question and ‘drip-feed’ this information as the need is identified by the group (without giving definitive answers) 4. Steer students towards certain ideas if key data is being missed out 5. Intervene if students are not working or if discussions become too tangential 6. Help students to formulate relevant learning objectives for further research (if help is required) 7. Ensure that classes run according to agreed timetables and monitor the attendance of students There is a delicate balance between prompting students to explore a problem in more depth and providing cues when students are lost and are evidently frustrated. Issues in implementing PBL There are various issues that you are likely to face when using PBL: Students Initially, PBL is often radically different from other approaches students have experienced, their expectations are often: “You are the teacher” “I can’t trust what student x has discovered” The facilitation model can vary to accommodate different levels of student experience, starting from a fairly directed style which incorporates more prompts from the tutor (or built into the scenario) through to a much more ‘hands-off’ approach with experienced students. The tutor can model and scaffold good teamwork practices. The skill levels of students in analysing problems and identifying learning issues can be very varied. Again the tutor needs to accommodate this variation. Other essential skills - researching, discussing, presenting and working as a team – can also vary widely, as does students’ perception of what ‘good’ work comprises. Some consider that “Google is the answer to every problem” Staff Similarly, academic staff/ tutors are often unfamiliar with facilitation. Their perceptions of teaching/ power/ skills may not be aligned with PBL. Other concerns 3 PBL can be conducted in short sessions, say an afternoon, through to scenarios that last several weeks, in multiple stages. The modularity of curricula does not help PBL, which works particularly well to integrate learning from various areas. Resources have always been an issue: PBL classically has a facilitator per group of 8-12 students. This does not align well with teaching / timetabling demands and organisation in many modern UK universities where class sizes are larger. There are ways around this, with either a ‘roving facilitator’ model or employing senior students as ‘learning team coaches’ (facilitators). In our experience the Computing scenarios work best with team sizes of 4-5 students. Assessment is a thorny area, PBL does not align well with exams, since the pressure of an exam at the end of the module tends to dictate the direction of learning (“is it on the exam?”) and therefore undermines the approach. One compromise is a seen exam, comprising a PBL scenario given out in advance. The amount of direction given to students depends on their experience: first year students or those new to PBL will typically require more direction, which means provision of more guidance and detail in the scenario/ resources. Experienced students should be given a messier scenario, with fewer resources. The Cybersecurity scenarios are provided in a customisable form so that users can adapt to suit their preferences and students. In short, the tutor decides on his/her objectives from the scenario, and by taking account of the students, makes the decision. Bessant et al (ND) provide an excellent toolkit for PBL which discusses the benefits, challenges, role of IT and social media together with advice over group work. Part 2: PBL approach used in the CSKE Scenarios Learning and consulting model It is recommended that students apply this model in each scenario as a means of learning an appropriate process for tackling similar problems. It adapts Woods’ PBL model by incorporating consulting skills appropriate for computing assignments. Learning Generic skills for PBL and consultancy The following table (Table 1) shows how the problem-solving model which we have adopted can be applied both to learning through our PBL learning scenarios and to a consultancy situation (e.g. working on secondment in an organisation as a consultant on a specific problem.) This shows that if students learn, apply and internalize the problem-solving process in a PBL context, they can transfer this approach to a professional consultancy context. Thus, students are learning professional skills and approaches alongside technical knowledge. 4 Table 1 The Problem- solving model mapped to the Consulting process and PBL Generic PBL process used in the Problem-solving model Consultancy process via secondment Cybersecurity scenarios Scenario analysis Desk research. Understanding Socio-technical organizational Meeting with supervisors to review 1 organizational history analysis. research and prepare for meetings. and context Clarification of ambiguities Clarification of ambiguities Requirements Analysis: identify Requirements Analysis: identify key key issues issues Simulated consultation with Data collection in the organization. stakeholders (e.g. through roleDetermining the Interviews with stakeholders. play and/or online interaction). 2 problem to be resolved Reviewing technology/ processes in Reviewing technology/ processes use. in use. Secure stakeholder/client support. Identifying learning goals. Initial report to academic supervisor. Facilitator Guidance. Individual research & learning to Identifying / Learning Individual research, learning & training resolve knowledge gaps. 3 necessary knowledge to resolve knowledge gaps. Summarising & reflection. and expertise Documentation & reflection. Teams share learning. Determine and agree evaluation Determining and agreeing criteria and process. evaluation criteria and process. Desk research. Market analysis. Identifying alternative Identifying technical possibilities, 4 Interviews with stakeholders. solutions considering acceptance issues and Identify technical possibilities organizational fit. considering acceptance issues and Facilitator Guidance. organizational fit. Deciding on best technical, Deciding on best technical, organizational and social organizational and social outcomes. Choosing optimal outcomes. 5 solution Propose solution with justification Proposing solution with Secure stakeholder/client support. justification Apply planning and scheduling Applying planning and scheduling techniques. Planning the techniques. 6 implementation Propose plan and deadlines. Proposing plan and deadlines. Ensuring stakeholder support. Building the solution (if Refine technical specification. appropriate). 7 Implementation Monitor implementation plan Deploying the solution (if Conduct progress reviews. appropriate). Formal evaluation methods re Formal report to organization. project success. Individual report to academic 8 Final evaluation supervisor. Personal reflection and Personal reflection and evaluation. evaluation. 5 Applying the generic PBL Learning Process in different educational or training contexts Table 2 demonstrates how the process can be adapted to suit different contexts. It shows how the process can be applied in an online context working with individual students where there is no face-to-face or team contact (Context 1) and in conventional teambased face-to-face PBL (Context 2). Table 2 The Problem- solving model mapped to online learners and Team-based PBL. 1 Generic PBL process used in the Cybersecurity scenarios Understanding organizational history and context Scenario analysis Socio-technical organizational analysis. Clarification of ambiguities 2 Determining the problem to be resolved 3 Identifying/ Learning necessary knowledge 4 Identifying alternative solutions 5 Choosing optimal solution 6 Planning the implementation 7 Implementation 8 6 Problem-solving model Final evaluation Requirements Analysis: identify key issues Simulated consultation with stakeholders (e.g. through role-play and/or online interaction). Reviewing technology/ processes in use. Identifying learning goals. Facilitator Guidance. Individual research & learning to resolve knowledge gaps. Summarising & reflection. Teams share learning. Determining and agreeing evaluation criteria and process. Identifying technical possibilities, considering acceptance issues and organizational fit. Facilitator Guidance. Deciding on best technical, organizational and social outcomes. Proposing solution with justification Applying planning and scheduling techniques. Proposing plan and deadlines. Building the solution (if appropriate). Deploying the solution (if appropriate). Formal evaluation methods re project success. Personal reflection and evaluation. Context 1: learner is working remotely as individual with online tutor support Individual review of scenario text and resources (e.g. clips of stakeholders) Learner raises any queries online and posts initial impressions to tutor. Context 2: learners are working in F2F team with facilitator and online access Individual and team review of scenario text and resources. Team discussion. Clarification of ambiguities with facilitator. Review Scenario text and resources with particular focus on stakeholder requirements Identify learning goals. Create individual action list & summary. Team review of scenario: identify key issues. Role-play of stakeholder interview(s) where appropriate. Team presentation of key issues. Identify learning goals. Team publish action list & summary in forum. Individual research & learning to resolve knowledge gaps. Summarize & reflect. Online tutorial if necessary Individual research & learning to resolve knowledge gaps. Summarize & reflect. Team share learning/ teach each other. Determine evaluation criteria. Individual identification of technical options considering acceptance issues and organizational fit. Learner posts progress report for tutor feedback Determine evaluation criteria through team discussion. Team identification of technical options considering acceptance issues and organizational fit. Facilitator Guidance. Individual decision and justification. Online report to tutor in role of main stakeholders Team decision and justification. Presentation to tutor in role of main stakeholders Review Scenario text and resources. Produce plan/schedule and risk analysis. Learner produces technical specification. Monitor implementation. Build/ deploy if appropriate. Individual evaluation of project success Individual reflection on personal learning & development. Review Scenario text and resources. Produce plan/schedule and risk analysis. Team presentation of technical specification. Monitor implementation. Build/ deploy if appropriate. Team evaluation of performance and project success. Individual reflection on personal learning & development. Resources Resources needed to support this form of learning comprise: 1. The problem scenario, including necessary background information and the problem to be solved. 2. A list of expected learning outcomes that the scenario is intended to help students achieve. 3. A list of resources students could use to learn the material 4. A facilitator guide that identifies potential solutions. References Bessant, S. (ND) Problem-Based Learning: A Case Study of Sustainability Education. Available online from http://www.keele.ac.uk/media/keeleuniversity/group/hybridpbl/PBL_ESD_Case%20Study _Bessant,%20et%20al.%202013.pdf This toolkit is one outcome of a three -year project, funded by the Higher Education Academy's National Teaching Fellowship Scheme. It provides useful illustrative examples and guidance for successfully implementing PBL. Boud, David, and Grahame Feletti, eds, The Challenge of Problem-Based Learning, 2nd Ed (London and Stirling: Kogan Page, 1997) An influential book which gives a thorough treatment with examples. Bridges,E.M. (1992) PBL for administrators, https://scholarsbank.uoregon.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1794/3287/pbl_admin.pdf?se quence=1 [Last accessed 11-Nov-15] A quite dated book, but good explanations about how PBL was implemented at Stanford. Duch, Barbara, Susan Groh, and Deborah Allen, The Power of Problem-Based Learning: a practical "how to" for teaching undergraduate courses in any discipline (Sterling: Stylus, 2001) An excellent ‘how-to’ book which shows how PBL can be used even with large classes, in a variety of subject disciplines. Newman, M. (2003). A pilot systematic review and meta-analysis on the effectiveness of problem-based learning. Last accessed 20-mar-11 from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.133.6561&rep=rep1&type=pd f One of the most comprehensive studies that explores the effectiveness of PBL. Savin-Baden, Maggi, Facilitating Problem-Based Learning: Illuminating Perspectives (Maidenhead: OUP, 2003) Being a successful facilitator is not easy, students complein about tutors who either do too little or teach. This book examines what it might mean to be an effective facilitator and suggests ways of designing problem-based curricula that enhance learning Schwartz, Peter, Stewart Mennin, and Graeme Webb, eds, Problem-based learning: case studies, experience and practice (London: Kogan Page, 2001) A useful set of case studies. Uden, Lorna and Chris Beaumont, Technology and Problem-based Learning, (Information Sciences: 2006) 7 A detailed explanation of the underpinning theory, methods and examples of PBL in Computing. Woods, D. R. (1995). Problem-based Learning: resources to gain the most from PBL, Donald R Woods. Don Woods provides an excellent set of resources, concentrating on developing the skills needed for successful PBL Woods, D. R. (1996). Problem-based Learning: helping your students gain the most from PBL, Donald R Woods. http://www.chemeng.mcmaster.ca/innov1.htm A student guide to help learners make the most of PBL and understand the approach Revision History V2, 11-Nov-1015 / CB 8