138260377591384587_paper

advertisement

A simple, quick and new design of scaling circuit for the

modulo set {22n 1,2n ,22n 1}

Fateme ghassemi ahangaran

Department of Computer Engineering Islamic Azad University

Kerman, Iran

ghassemi.fateme@iauk.ac.ir

ABSTRACT

In this study a new and unique design of the residue number system scaling circuit for the 3moduli

set {2 1, 2 , 2 1} which has a dynamic range over 5n is presented. Nowadays 5n dynamic range has

2n

n

2n

proved to be of good performance. The relations in this study are obtained by Chinese Remainder Theorem

which is one of the most important conversion algorithms in residue number system.

Key words: residue number system, dynamic range, scaling, scale.

1. INTRODUCTION

As number system different from the conventional ones, the residue number system has attracted

more attention from computer calculations scientists in recent a decade which is a result of its unique

features and their applications for special-purpose processors. Residue number system has played an

important role in computer calculations for ages. This advantage is revealed with the limitation of the carry

propagation [1]. As a result performing the calculations in this system can lead to a decrease in delay,

hardware cost and power consumption [2]. In residue number system production of carry is parallel, though

as we know in other systems distribution chain of the carry is long and makes the process slow.

Consequently in the residue number system adding, operations of addition, subtraction and multiplication

are done quickly. This system has widespread uses such as digital signal processing including digital filters,

picture processing, designing code detection and correction algorithms (in designing safety systems), and

encoding[1],[3]. This system can be used specifically in designing Inner Product Step Processor. The

primary and most important procedure for designing this system is selecting a modulo set which is prime

two by tow, and multiplying them by each other results a dynamic range that shows the number of visible

1

numbers in this system[1]. For transforming weighted numbers (conventional system) for this system, we

should divide the preferred number by each member of the set and the residues are usable for calculating in

this system. So far various modulo sets have been offered in residue number system that can be categorized

by dynamic range and number of members. Examples of such sets would be: 2 n 1, 2 n , 2 n 1 ,

2

n 1

2

1, 2 n 1, 2 n ,

n

1, 2n , 2n 1 1 . DRs resulting by these modulo sets are not suitable for

applications with greater range. Recently modulo sets with greater dynamic range are popular. As

mentioned above in this study we tried to present scaling circuit for modulo set {2 1, 2 , 2 1} which

has a dynamic range over 5n bit. At first RNS was paid a lot of attention by computer science but due to

some problems and hardware malfunctioning, its use was abolished. Though in recent years, they came

back by extended use of special-purpose processors and increase in hardware capability in implying

complex circuits. Types of hardware meant here could be direct and reverse conversion, various full adders

used in them, modulo multiplexers, sign detection circuits, comparing circuits and scaling circuits.

Performance boost in any of these circuits can play a significant role in system performance. The point here

in this system is that some designing some of the mentioned hardware circuits is by considering algorithms

that are used in reverse conversion, ones like Chinese Remainder Theorem, conversion in co-based

algorithm and Chinese Remainder Theorem 1 and 2. Here Chinese Remainder Theorem can be applied

quickly and parallel and as a reason we used it in this study for the anticipated circuits. Aside from the

advantages to residue number system it has disadvantages too. RNS is costly in sign detection, division,

and competing, reverse conversion and scaling and in fact has a lot of problems. The tow latter are more

urgent to be solved because they are the gateway to design the circuit for conversing numbers from residue

to binary systems. In fact reverse means return from residue system to binary system which is a costly and

complicated operation and scaling circuit is used for preventing overlapping after each calculation

procedure[4]. The difference we can see between scaling and division is that in practice division makes

each number in the system a fixed value and we seek the quotient, while in scaling we look for the residue

from the number in conventional system by each module in the modulo sets and want them to be calculable

using the resulting numbers from residue number system. It can be claimed that in scaling, division

operation is omitted meaning that a series of individuals helps derive another series of individuals. In

scaling, system’s input and output are both residue considering the modulo set. So we should design scale

circuits as many as set members.

2n

n

2n

2. PREVIOUS WORK

Designing scaling circuits was first discussed by Szabo & Tanaka in 1967. At that time calculation

period was in a cycle as long as n clock that n resembled the number of modulo set members. Their

suggested method was not error free though it was considered advancement in RNS [6]. In 1973 Okeefe &

Wright designed a circuit for the modulo set {2 1, 2 , 2 1} which was more effective than Szabo’s

but was also not error free as well, though it gave closer answers[7]. In 1978 Jullien managed to present an

algorithm that needed fewer clocks but also accompanied some errors[8]. In 1981 Taylor & Huang made a

design that despite all previous ones that were based on CRT algorithm, used MRC method in its

calculations [9]. A year later these two presented a model that was an idea based on modulo sets and LUTs,

but like others needed a long n clock of time [10]. In 1984 Polky & Miller presented a new algorithm that

needed (N+1) clock of time and the value obtained from it was closer to real value. In fact it carried fewer

errors than previous offers but claimed more time [11]. Five years later Shenoy & Kumarson offered a

design for scaling that needed a period of log n that was much more considerable than the preceding offers

[12]. Finally in 1993 Ulman wrote an essay based on SZabo’s work and promoted his method to a lot of

extent [13]. From then on, a lot of suggestions were made in this field but the point is that there were errors

in all algorithms but the value didn’t exceed 1.5 units [5]. At that time scaling circuits were applied bye

ROM memory and this made the processes slow and power consumption high. Due to this reason

researchers were always looking for a way to solve this. However ROM matrixes can be replaced by

multiplexers, it increased the cost unacceptably. We would like to mention that there are two ways to

design algorithms; one using LUTs and the other by accessing through full adders and almost in all designs

based on memory, the cost increases as the number of modules do, while designs with full adders are faster

and claim less area. In 2011 Chang could offer a new perspective in scaling circuits by modular full adders

2n

n

2

2n

which resulted in speed increase and less power consumption[5]. It is necessary to mention that there are

also other scaling circuits that benefit from both technologies of LUT and full adders, but in among these

circuits, Chang’s is the fastest and the most efficient. A weakness for this circuit would be that it is a design

for 3member modulo set {2 1, 2 , 2 1} with a dynamic range of 3n bit which does not suffice for

today’s computer needs. Chang also surveyed scaling circuits for signed numbers in a paper in 2012.

2n

n

2n

3. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

As mentioned above there are two ways to do scaling algorithms, one using LUTs [14],[15]and the

other access through full adders[16-19]. At first all algorithms used ROM but scaling algorithms their

problem was high power consumption. However ROM matrixes can be replaced with modular

multiplexers, this increases the cost unacceptably. This cost increase would be much more for greater

modulo sets. As pointed before almost all designs based on memory increase the cost as the modules’

number increases, while if those designs are manipulated with full adders it would be faster and would

claim less area[15]. In this study we surveyed designing a scaling circuit for the modulo set

{2 1, 2 , 2 1} .

2n

n

2n

CRT algorithm is defined as below:

N

CRT : X

M

3

1

i

Mi

i 1

X

xi

mi

M

M

i 1

1

i

1

m 2m 3 M 1

Mi xi

1

m1

x 1 m 1m 3 M 2

1

m2

x 2 m 1m 2 M 3

M

m3

x3

M

(1)

As we know dynamic range is obtained from multiplying modulo set members, so:

N

3

i 1

i 1

(2)

M m i m i (22 n 1)(2n )(22 n 1)

Here are some relationships that can be used for simplifying existing scaling relationships and designing

offered circuits.

A X

B

X Y

X .Y

aP1

m

P1 P2

(3)

AX

m

AB

X

X

m

Y

(4)

m m

(5)

m

.Y

m m

(6)

a P P1

2

If z is an n bit number then:

z

2n 1

(7)

z 2

Supposing p kq , if k is an integer then X

p q

X

use the below rules:

X

p

q

always applies. For proving this rule we could

(8)

X p

0,1, 2,...

Considering rules (4) and (5) it can be inferred that:

3

X

p q

X p

X

q

q.p

q

(9)

q q

Since p kq and in other words p is dividable by q, p q 0 then:

X

p q

X

(10)

q

2n

2n

If m 1 2 1 , m 2 2 and m 3 2 1 For calculating M i s we act as below:

n

M 1 m 2m3 M 1

M

2

m1m 3 M

M

3

m1m 2 M

2

(11)

(22 n 1)(2n )(22 n 1)

(22 n 1)(22 n 1)

(2n )

(12)

(22 n 1)(2n )(22 n 1)

(22 n 1)(2n )

(22 n 1)

(13)

3

(22 n 1)(2n )(22 n 1)

(2n )(22 n 1)

(22 n 1)

The reverse of needed multiplexers is gotten as below:

M

1

i

Mi M

1

i

mi

1

1

1

M1 : M1 M1

1

n

1

1

3

1 (2 )(2

m1

M 2 : M 2 M 2

M : M M

3

1

3

1 (2

m2

2n

1

1) M 1

2n

1)(2

1 (2 1)(2 ) M

2n

m

(14)

n

3

2n

2n

(2

2n

1 M 1 (2

1)

1

1 )

1 M

n

(2 )

1

3

n 1

)

(15)

1 M 2 ( 1)

(16)

1

1) M 2

1

3

1

(2

n 1

(2 )

(17)

Here we suppose Scale S m 2 2 (the second modulo). So y is:

n

X 1 m m M 1 x m m M 1 x m m M 1

1

3

2

2

1

2

3

m

m

k k 2 3 1 m 1

mm

m 1m 3

m m

1

1

1

2

3

M1

x1

M2

x2 1 2 M3

x3

m

m

m

M

k

k

k

k

Y

1

Y

2

1

Y

Y

X

m m3

2

X

k

2

1

M1

m1

1

m3 M 1

mi

m1

x1

x1

m 1m 3

m2

m1m 3

m2

3

x3

M

3

1

M2

1

m2

x 2 m1 M 3

m3

x3

m1 m 3

1

M2

1

m2

x 2 m1 M 3

m3

x3

(18)

m1m 3

Based on rule (10) for i=1, 2, 3 simplifying continues as below:

4

mi

X m M 1 x m1m 3 M 1 x

3

1

1

2 m

2

m

k m

m2

m

i 1 y1

1

(19)

2

1

1

X m M 1 x m 1m 3 M 1 x m M 1 x

3

1

1

2 m

2

1

3 m

3

m

k m

m2

i 2 y2

1

2

(20)

3

m1 m 3 m

2

2

X m1m 3 M 1 x m M 1 x

2 m

2

1

3 m

3

k m

m2

m

i 3 y3

2

(21)

3

3

3

At first we derive values that are repeated in all relationships:

m1 M 31

m3

m 3 M 11

m1

(21)

(22 n 1)(2n 1 ) (23n 1 2n 1 )

(22)

(22 n 1)(2n 1 ) (23n 1 2n 1 )

1

n

(2 1)(2 1)

2n

m1m 3

1

M2

m2

m2

2n

n

( 1)

(2 )

m2

In the above statement we omit

If k 1 2

3 n 1

m1m 3

1

2n

(2 1)

4n

1

M2

m2

2

n

(1 2 )

2 (

4n

( 1)

2

n

2

n

2

2 )

3n

n

1

2

n

2 2

3n

(23)

3n

, to analyze this omission we can write:

2n 1 and k 2 23n وk 3 23n 1 2n 1 and also p m1m 3 then:

x k x k x k x

k 1 1 2 2 3 3 p

/

Using rule (4-8) we could reconstitute the above statement as below:

x k x k x k x p k x k x k x p

1 1 2 2 3 3

k 1 1 2 2 3 3

/

In a way that

x (2

k

If

c (

3 n 1

2

is a non-negative digit. Without the replacements of k 1 ,

n 1

1

)x (

3n

2 ) x (2

1

n

2

2

3 n 1

2

n 1

)x

3

kx

1

m m

1

3

k 2 and k 3 rule (23) will be like:

1

1

(k

)x k x

2

n

2

2

3

3

1

p

x2

) is named, then we can simplify the above relationship as follows:

2n

5

k x

x

1

k x

2

2

2

n

2

k x

3

3

p

x k x k x k x c k x k x k x c p

1 1 2 2 3 3

p

k 1 1 2 2 3 3

x k x

k

1

1

k 2 x 2 k 3 x 3 p c

Since 0 x 2 2 , then we can write:

n

c

x2

2

n

0 c 1 c 0

It can be concluded from the above relationships that:

x

k

/

x

k

Now using the above replacements and notes below, we derive y i formulas of preferred scaling circuits.

Note 1: if a k bite digit (such as v) is multiplied by a 2 n and we want the result in modulo

( k ) bits

(2 1) , 2

k

n

then the answer equals n-bit circular shift to the left of the desired digit.

v

k

2 1

( k )bits

Note 2: if v is negative v

then the result equals the complementary of the digit v.

2 1

k

3.1. Calculating

y1

X

k m

y1

A

1

m3 M 1

m1

x1

m1m 3

1

m2

1

M2

m2

(2

x2

2n

1)(2

B

n 1

(24)

) x 1 ( 2 ) x 2

3n

m1

2

2n

1

To calculate value of A using note (1) we have:

A : (22n

1)(2n 1)x

2n

(2 1) 2n 2

2 1

1 22n 1 n 1

(2 )

(2n 1)

22n 1

n 1

n

2(2 ) 2

(nbits )

(2n )x 1

Also for B we can write:

( nbits )

B : (2 )x 2

3n

( 2 ) x 2

n

22 n 1

22 n 1

( nbits )

( x 2, n 1 ......x 2,0 ,11.......1)

6

22n 1

(nbits )

( x 1,n 1,......, x 1,0 , x 1,2n 1,......, x 1,n )

Finally y 1 is gotten as below:

y 1 value is designed.

This shape below illustrates how

x

x

1

2n

2

n

Operand Preparation

Unit

y

12

y

11

2n

2n

Modular (2

2n

-1) adder

2n

y

1

Figure 1. Hardware of y 1

3.2. Calculating y 2

To prevent sophistication of

that has the below value, we can divide it into the 3 sub-

y 21 , y 22 , y 23 .

formulas

y2

y 2 calculation

X m M 1 x m 1 m 3 M 1 x m M 1 x

3

1

1

2 m

2

1

3 m

3

m

k m

m2

m m

1

2

3

2

y2

X

k

1

(2 1)(2 1)( 1)

2n

n 1

(2 1)(2 ) x 1 (

2n

m2

(2 )

2n

y 23

(2

Now we can simplify for each part like this:

y 21

y 21 as below:

Using rule (4-6), we can simplify

p1

y 21 (2 1) (2

2n

a

n 1

)x 1

p2

(2

2n

1)( 2

p1

2n

(2 n 1 ) x 1

(25)

n 1

) x 2 (2 1)(2 ) x 3

y 22

3.2.1. Calculating

m2

2n

n

y 21

3

(2

2n

1)

1)

7

(2 2 n 1)

2n

1)( 2

2n

1) 2 n

( n 1) bits

( n 1) bits

y 21 ( x 1, n ......x 1,0 , x 1,2 n 1 ......x 1, n 1 ) (2 2 n 1)

( n 1) bits

( n 1) bits

( n 1) bits

( n 1) bits

(26)

y 21 ( x 1, n ......x 1,0 , x 1,2 n 1 ......x 1, n 1 , x 1, n ......x 1,0 , x 1,2 n 1 ......x 1, n 1 )

2.2.2. Calculating y 22

Using the simplification that resulted in (23), for y 22 we can have:

y 22 ( 2 ) x 2

( n ) bits

( n ) bits

(3 n ) bits

2 (00......0 , x 2, n 1 ......x 2,0 )

3n

2

4 n 1

(3 n ) bits

(27)

( x 2, n 1 ......x 2,0 ,11......1)

3n

2

4n

1

3.2.1.Calculating y 23

With the above rules and relationships we can also simplify y 23 as below:

y 231

n 1

y 23 (2 1)(2 )x 3

2n

2

4n

1

y 23 (2

y 232

3 n 1

2n 1 )x 3

2

(2 n 1)bits

y 231 (2

3 n 1

)x 3

2

4n

1

2

3 n 1

( n 1)bits

4n

4n

1

( n )bits

( 2 n 1) bits

4n

( n 1)bits

1

(2 n 1)bits

( n )bits

( n ) bits

(2 n 1)bits

y 232 (11......1, x 3,2 n ......x 3,0 ,11......1)

2 (00......0, x 3,2 n ......x 3,0 )

2

( n 1) bits

( n )bits

1

(2 n 1)bits

n 1

2

(2 n 1)bits

y 231 (x 3,n ......x 3,0 ,00......0, x 3,2 n ......x 3,n 1 )

(00......0, x 3,2 n ......x 3,0 )

2

y 232 (2 )x 3

1

(2 n 1)bits

(2 n 1)bits

n 1

4n

( n 1)bits

(28)

y 23 (x 3, n ......x 3,0 , 00......0 , x 3,2 n ......x 3, n 1 ) (11......1, x 3,2 n ......x 3,0 ,11......1)

Now with having the value of y 21 ,

y 2 y 21 y 22 y 23

2

y 22 , y 23

we can finally calculate y 2 .

(29)

n

y 22

y 21

( n 1) bits

( n 1) bits

( n 1) bits

( n 1) bits

( n ) bits

y 232

y 231

(3 n ) bits

( n 1) bits

(2 n 1) bits

( n ) bits

( n )bits

(2 n 1)bits

( n 1)bits

y 2 ( x 1, n ......x 1,0 , x 1,2 n 1 ......x 1, n 1 , x 1, n ......x 1,0 , x 1,2 n 1 ......x 1, n 1 ) ( x 2, n 1 ......x 2,0 ,11......1) ( x 3, n ......x 3,0 , 00......0 , x 3,2 n ......x 3, n 1 ) (11......1, x 3,2 n ......x 3,0 ,11......1)

2

Designing y 2 is as follows:

8

4 n 1

2n

x1

x 2

n

x3

n

(2n+1)

Operand Preparation

Unit

y

21

4n

y

22

4n

y

231

y 232

4n

4n

(4n-bit)CSA with EAC

Modular(2

4n

-1)adder

n

y

2

Figure 2. Hardware of y 2

3.3. Calculating y 3

Like the 2 previous parts, to calculate this part we use the mentioned rules and relationships.

y3

X

k

B

A

m1m 3

m2

m3

1

M2

1

m2

x 2 m1 M 3

m3

x3

m3

X (23n ) x (22 n 1)(2n 1 ) x

y3

2

3

k m

3

2n

2 1

A : ( 23 n ) x 2

2n x 2

2 1

y 3 B : (2 2 n 1)(2 n 1 ) x 3

(23 n 1 2 n 1 ) x 3

y

y

y 2n (x x )

2

3

3

2n

2

2n

1

2

31

2

2n

1

2n

1

2n

1

( 1)

( 2 n ) bits

1bit

( x 3,2 n 2 ) ( x 3,2 n 1 .......x 3,0 )

( 2 n ) bits

(31)

( x 3,2 n ) ( x 3,2 n 1 .......x 3,0 2)

2

And lastly for

1

(30)

2n

2n

2n

y 32 we can have:

negative

2

2

(00......0 , x 2, n 1 .......x 2,0 )

Considering rule (7), for

n

1

1

2

y 32 ( 2 ) x 3

2

( n ) bits

( n ) bits

y 31 2 ( x 2 )

1

( 2 n ) x 3

2n

32

2

n

2n

2n

1

2

y 3 we can have:

9

2n

1

y 3 y 31 y 32

( 2 n 1) bits

( n ) bits

( n ) bits

( 2 n ) bits

1bit

2 ((00......0 , x 2, n 1 .......x 2,0 ) (00......0 , x 3,2 n ) (x 3,2 n 1 .......x 3,0 ) 2)

n

2

2n

1

y 31

We can define y

*

y 32

y 33

(32)

2

2n

1

to organize the above rule as below.

(2 n 1)bits

(2 n 2)bits

1bit

2bits

y y 32 2 (00......0, x 3,2 n ) 2 (00......0,1x 3,2 n )

*

y 32

And at last for

y 3 we have:

( n )bits

(2n 2)bits

( n )bits

(2n )bits

2bits

y 3 2 n (( 00......0 , x 2,n 1.......x 2,0 ) ( 00......0 ,1x 3,2n ) ( x 3,2n 1.......x 3,0 ))

y 31

y 33

y*

(33)

22 n 1

And the shape resulted from the above rules is like this.

x

x3

2

Operand Preparation Unit

y31

y*

2n

2n

Multi Modular ( 2

y33

2n

2n

+1)Adder

y

3

Figure 3. Hardware of y 3

4. CONCLUSION

As it was explained in the beginning of the article, using the residue number system in computer

systems is one of the imminent problems for the lack of efficient hardware necessary. This problem can be

tackled with designing scaling circuits to a great extent. Needing to use modulo sets with larger dynamic

ranges, we chose modulo set

2

2n

1, 2 , 2 1 . This design caused the omission of division operation

n

2n

and the transforming reverse unit for calculating the overlap in residue number system. As we know in

RNS we are supposed to take the residues resulted from preferred modulo set to the conventional number

system with using the reverse transformer and then do de division on them and formerly transfer the digit to

residue system and this can be costly and time consuming. While there is no need to do these operations in

scaling circuits and we can get the division residues directly from the residues available in RNS system

without need to use reverse transformer or division. As follows we prove scaling circuits improving role in

residue number system with presenting an example.

Without using scaling:

10

Here as an example we assume that n=3, then modulo set will be {63,8,65}. If preferred numbers’ residues

of this set are{24,5,51}, we should firstly transfer the preferred digit to conventional number system that is

performed by Chinese residue algorithm:

n 3 M .S {63, 8, 65}

{x 1 , x 2 , x 3 } {24, 5, 51}

M 63 8 65 32760

32760

M1

63

32760

M1

8

32760

M1

65

520 M 11 : 520 M 11

4095 M

1

2

2

1

X (x 1 M 1 M 1 ) (x 2 M

2

M

1

2

1

536

1

n

2

2

: 4095 M

504 M 31 : 504 M 31

2n

2

2n

1

4095

504

) (x 3 M 3 M

1

3

)

32760

X (24 520 536) (5 4095 4095) (51 504 504)

32760

X 1221

Y

X

2

n

1221

152

8

y 1 152%63 26

Y 152 { y 1 , y 2 , y 3 } ? y 2 152%8 0

y 152%65 22

3

{ y 1 , y 2 , y 3 } {26, 0, 22}

Up to this step we have only developed preferred digit in residue system. Now we should divide it by the

scale that is 8 here in this example (it is obvious that division operation in computer calculations is costly

and time consuming), and again transfer the digit to residue number system.

X

1221

152

n

2

8

Y 152 { y 1 , y 2 , y 3 } ?

Y

y 1 152%63 26

y 2 152%8 0 { y 1 , y 2 , y 3 } {26, 0, 22}

y 3 152%65 22

Now we survey through the above calculations and relations with the use of scaling.

With using scaling:

n 3 M .S {63, 8, 65} {x 1 , x 2 , x 3 } {24, 5, 51}

y 1 2 (x 1 x 2 )

n

y 2 (2

2n

1)(2

2

2n

n 1

1

8(24 5)

63

26

) x 1 ( 2 ) x 2 (2

3n

2n

1)(2

n 1

y 2 (65)(4)(24) ( 512)(5) (63)(4)(51)

y 3 ( 2 ) x 2 (2

3n

2n

1)(2

n 1

)x 3

)x 3

4095 8

22 n 1

y 3 (512)(5) (63)(4)(51) 65 22

11

2

4n

1 2

0

n

It is concluded that using scaling can improve residue system’s efficiency in computer calculations to a

great extent.

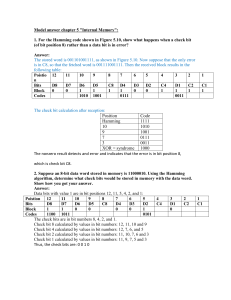

As a final point we survey the results of implementing scaling circuits for the presented modulo set. We

would like to mention that designs were firstly transformed to VHDL codes and then using Modelsim

software we plotted them in terms of design performance. After making sure of the accuracy of what we

did before, they were simulated for various values using software ISE on different technologies (Virtex4 ,

Virtex5 & Virtex6).

Charts of implementation results in Area lines according to Slice, LUT and Latency are announced.

Table 1. Result for moduli set 2 1, 2 , 2 1 with virtex4

2n

n

2n

Virtex 4

2

2n

Area (Slice)

Area (LUT)

Latency (ns)

N=4

94

156

6.254

N=8

171

283

7.790

N=16

330

551

9.219

N=32

639

1086

11.627

N=64

1308

2158

16.441

1, 2n , 2 2 n 1

Table 2. Result for moduli set 2 1, 2 , 2 1 with virtex5

2n

n

2n

Virtex 5

2

2n

Area (Slice)

Area (LUT)

Latency (ns)

N=4

44

110

5.371

N=8

84

230

7.054

N=16

164

447

7.628

N=32

322

820

8.012

N=64

638

1534

8.961

1, 2n , 2 2 n 1

12

Table 3. Result for moduli set 2 1, 2 , 2 1 with virtex6

2n

n

2n

Virtex 6

2

2n

Area (Slice)

Area (LUT)

Latency (ns)

N=4

44

84

2.939

N=8

84

214

4.966

N=16

164

420

5.592

N=32

322

796

6.328

N=64

638

1492

7.641

1, 2n , 2 2 n 1

As shown in charts all the three technologies Virtex4 , Virtex5 & Virtex6, are increased as n value

increases (calculated values for Area according to Slice , LUT and latency are per nanosecond).

In chart 1 average rate of Area (slice) column compared to Area (LUT) column is 1.6. It means the

calculated area according to LUT equals 1.6 times the calculated area according to slice with the same n

value.

In chart 2 increase in Area column values according to Slice compared to Area column according to LUT

has an average rate of 2.56. Here again with increasing n value by 2 times, the area acquired from both

Slice and LUT units has 1.93 times average rate and latency has had a growth 1.13 times average rate.

Values obtained from chart 3 show that the increase of Area column according to Alice compared to LUT

is 2.32. Doubling n value, the area calculated from Slice and LUT columns have growth rate of 1.94. This

value for Latency is 1.07.

With an overall look at the calculated numbers, it can be stated that in Virtex5 we observed the most

average growth rate compared to areas resulting from Slice and LUT. The highest average growth rate

belongs to Latency column of Virtaex6.

13

References

[1] Molahosseini, A. S.,Navi, K,Dadkhah, C., Kavehei, O.,Timarchi, S., (2010)." Efficient Reverse

Converter Designs for the new 4-moduli Sets 2n 1, 2n , 2n 1, 2 2 n 1 1 and 2n 1, 2n 1, 22 n , 22 n 1 Based

on New CRTs". IEEE Trans. Circuits and Systems-I, 57, 823.

[2] Molahosseini, A. S., (2011). "Improving the Delay of Residue-to-Binary Converter for a Four-Moduli

Set". Advances in Electrical and Computer Engineering, 11.

[3] Chang, C. H., Low, J., Y., S. (2011). "Simple,Fast and Exact RNS Scaler for the Three-Moduli Set

n

n

n

2 1, 2 , 2 1 ". IEEE Trans. Circuits and Systems-I, 58, 2686-2697.

[4] Safari, A., Cong, Y. (2012). "Simple,Fast and Synchronous Hybrid Scaling Scheme for the 8-bit Moduli

Set 2 1, 2 , 2 1 ". Journal of Emerging Trends in Computing and Information Sciences.

n

n

n

[5] Anders Lindström, Michael Nordseth, Lars Bengtsson, Amos Omondi, "Arithmetic Circuits Combining

Residue and Signed-Digit Representations," Proceedings of the Eighth Asia-Pacific Computer Systems

Architecture Conference, vol. 2823, 2003.

[6] G. A. Jullien, "Residue number scaling and other operations using ROM array," IEEE Transaction

Coniputer, vol. 27, pp. 325-336, 1978.

[7] F. J. Taylor and C. H. Huang, "A floating point residue arithmetic unit," vol. 311, pp. 33-43, 1981.

[8] F. J. Taylor and C. H. Huang, "An autoscale residue multiplier," IEEE Trunsaction Computer, vol. 31,

pp. 321-325, 1982.

[9] D. D. Miller and J. W. Polky, "An implementation ol the LMS alalgorithms in residue number

system," IEEE Trunsaction Circuits System, vol. 31, pp. 452-561, 1984.

[10] A. P. Shenoy and R. Kumaresan, "Fast base extension using a redundant modulus in RNS," IEEE

Transaction Computer, vol. 38, pp. 292-297, 1989.

[11] Z. D. Ulman, M. Czyzak, J. M. Zurada, "Effective RNS scaling algorithm with the Chinese remainder

theorem decomposition," IEEE Pacific Rim Confference Communication, Computer, Signal Process,

pp. 528-531, 1993.

[12] R. Zimmermenn, "Efficient VLSI Implementation of Modulo (2^n-1) Addition and Multiplication,"

Computer Arithmetic, pp. 158-167, Apr 1999.

[13] R. Zimmermann, "Binary Adder Architectures for Cell-Based VLSI and their Synthesis," SWISS

FEDERAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, ZURICH, 1997.

[14] Shenoy, M. A. P., Kumaresan, R. (1989) “A fast and accurate rns scaling technique for high speed

signal processing,” IEEE Trans. Acoust, Speech, Signal Process, 37, 929–937.

[15] Ulman, M. C. Z. D., Zurada, J. M. (1993) “Effective rns scaling algorithm with the chinese remainder

theorem decomposition,” IEEE Pacific Rim Conf. Commun., Computer, Signal Process, 528–531.

[16] Griffin, F. T. M., Sousa, M.( , 1988) “New scaling algorithm for the Chinese remainder theorem,”

Proc. Conf. Rec. 22nd Asilomar Conf Signals, System., Computer , 375–378.

14

[17] Kong, Y. Phillips, B. (2009) “Fast scaling in the residue number system,”Very Large Scale

Integration (VLSI) Systems, IEEE Transactions on, 17, 443 –447.

[18] Dasygenis, M., Mitroglou, K., Soudris, D., Thanailakis, D.(2008)“A full-adder-based methodology

for the design of scaling operation inresidue number system,” Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers,

IEEE Transactions on. 55, 546 –558.

[19]Benardson, P. (1985) “Fast memoryless, over 64 bits, residue-to binary convertor,” Circuits and

Systems, IEEE Transactions on, 32, 298 – 300.

15