![[A Trio of Seminars—Short Version: Seminar Three 8.iv.2013] A Trio](//s3.studylib.net/store/data/007004909_1-ee1380b1f942c4f4804ae8ae893cec62-768x994.png)

1

[A Trio of Seminars—Short Version: Seminar Three 8.iv.2013]

A Trio of Seminars on Sovereignties – Seminar Three

The Third Sovereignty Seminar: The Individual*

Peter McCormick

Individual Sovereignties

Overview

§14. Individual Sovereignties

14.1 A Composite Account of Self-Sovereignty

14.2 Immanence and Transcendence

14.3 Evaluating the Composite Account

Discussion Seminar Three §14 and Concluding Remarks

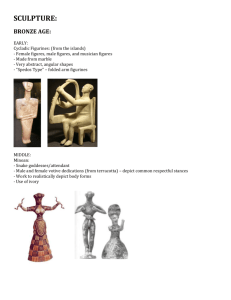

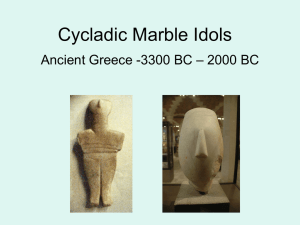

§15. Cycladic Europe: the Marble Lady of Naxos

15.1 Early Cycladic Marble Figurines

15.2 Nature and Provenance

15.3 A Canonical Folded-Arm Figurine

15.4 Another Folded-Arm Figurine

Discussion Seminar Three §15 and Concluding Remarks

*Copyright C 2013 by Peter McCormick. All Rights Reserved.

Draft Only: not authorized for citation in present unrevised form.

2

§16. Cultural Meanings

16.1 Cultural Meaning

16.2 Religious Contexts

16.3 Meanings: Philosophical vs. Cultural?

Discussion Seminar Three §16 and Concluding Remaks

§17. Philosophical Significance: TBA

17.1

17.2

17.3

Discussion Seminar Three §17 and Concluding Remarks

§18. A Third Set of Interim Conclusions:

Bounded Sovereignties III (TBA)

18.1 Endogenously limited individual sovereignties

18.2 Exogenously limited individual sovereignties

18.3 Religiously limited individual sovereignties

3

In Brief

A final stage of our inquiry here into the earliest European

backgrounds for an enlarged understanding of today’s overly

narrow interpretations of sovereignty as almost exclusively state

sovereignty focuses now on the idea neither of limited political

sovereignty nor of limited social sovereignty but on that of

individual sovereignty as also necessarily limited.

We begin as earlier with a critical description and appraisal of

another contemporary account of individual sovereignty under

the guise of a so-called composite account of self-sovereignty.

Recalling several salient details of this account will then sharpen

our awareness of what we may be able to retrieve from another

step back into the Aegean Bronze Age historical and conceptual

origins of modern notions of individual sovereignty that are still at

the center of our reflections today.

Proto-European Aegean Cycladic cultures (ca. 3200-2000 BCE

arguably reached one its several highpoints in the sculptured

human forms first developed in the Early Cycladic II Period from

2800 to 2300 BCE.1

The symbolic representations of this highpoint of Cycladic culture

may be found especially in the unprecedented sculptural

creations of what appears to have been a loosely related school

of outstanding artists.

Archeological interpretations of one of these artist’s most

striking creations point to the fundamental salience of a certain

form of individuality. This individuality is very carefully traced in

the sculpturally detailed forms of individual standing persons,

mostly but not exclusively women, called figurines.

I follow here the development charts of K. Iliakis reproduced in Daskalakis 1994 and

Doumas 2000.

1

4

The quite particular characterization in these figurines is evident

in the various artistic means chosen not just to stylize but also to

individualize a genuine kind of individual sovereignty.

This individualized sovereignty may perhaps best be illustrated

with the details of the outstanding Folded-Arm Figurine from the

Spedos Phase of Cycladic culture with its sculpted torso, lower

body, and carefully shaped legs together with its lyre-shaped and

upward turned flattened face.

This individualized sovereignty, however extensive, was

nonetheless also clearly limited by at least the creation of other

major figurines in several other competing Cycladic island

workshops such as at Saliagos, Melos, and elsewhere.

*****

§14. Individual Sovereignties

In Seminar Two we focused on the significance of the Middle

Minoan culture’s male statuette, the Palaikastro Kouros, for identifying

representations of several more of the earliest settled European

values. With the help of the reflective work of John Rawls and Jürgen

Habermas we also saw how some artistically represented ethical

values might be taken as provoking second thoughts today about just

what ethical and in particular social values might figure in various

draft preambles to an historically sensitive eventual EU constitution.

We need now in Seminar Three to deepen our reflective concerns

with a larger than exclusively political understanding of sovereignties

in the light of culturally meaningful and philosophical significant

aspects today of some of the most significant artworks from the

origins of European civilization in the Bronze Age Aegean.

After our reflections on political sovereignties in the first part of

5

our inquiries and then on social sovereignties in the second part, we

now take up in this third and final part related issues concerning

individual sovereignties. Some distinguished work in contemporary

political theory will be our initial guide.2

14.1 A Composite Account of Self-Sovereignty

In her 2005-2006 Gifford Lectures, published in expanded form

under the title Sovereignty: God, State, and Self,3 Jean Bethge-Elshtain

sets out both an historical as well as thematic account of different

kinds of sovereignty. Her perspective, like that of R. Jackson (2007)

whom we took as our initial guide in Seminar One, combines both

political science and the history of ideas.

Unlike Jackson’s perspective, however, Bethge Elshtain is more

concerned with political theory rather than with political science as

such. Moreover, she places much more historical emphasis on the

medieval and pre-modern periods. Still more, unlike Jackson she

explores in great detail both the natural theologies of Augustine and

Aquinas as well as the work of the central Protestant reformers, Luther

and Calvin.

Finally – and it is this aspect of her account that will occupy us

here – Bethge Elshtain’s account of sovereignty pays much attention to

the idea of the self, or what she calls “self-sovereignty,” in the

contexts of personal or individual sovereignty. because the scope of

her treatment of sovereignty is much wider than any exclusively

Note that political theory as a field of inquiry is identical today with neither political

science nor with political philosophy.

2

New York: Perseus Books, 2008. Unless otherwise noted, further references here to

this book are enclosed in parentheses in the text.

3

6

political account or social account, we will find it convenient to refer

to her work hereafter as a “composite account” of sovereignty.4

The first key idea in this composite account derives from the

understanding of medieval political theory in terms of “a bewildering

variety of overlapping jurisdictions, none of which could claim de facto

the kind of absolutism that sovereigns began to embrace from the

sixteenth century or so on” (p. xv). These overlapping jurisdictions,

while requiring today fresh analysis and discrimination, nonetheless

had the virtue of taking sovereignty itself as being an “inclusive” rather

than an “exclusive” notion.

That is, not only political but also religious considerations were

then understood as being part of the basic notion of sovereignty itself.

In this respect, medieval political theory might be said to have imitated

medieval practice where no clear borders stood between the regnum

and the sacerdotum (pp. 40-47).

5

Now, part of the greatness of Hobbes’s achievements with

respect to delimiting the notion of sovereignty was to eliminate all

such overlaps by taking political sovereignty as absolute sovereignty.

Thanks largely to that extraordinary work, the Westphalians6 in 1648

were able conceptually to mark out absolute state sovereignty in such

clear, if later much disputed, terms that the recurring devastations and

4

For another composite account see Philpott 2001.

5

Cf. Jackson 2007, pp. 24-33.

For the Westphalians and “Westphalian sovereignty” see Philpott 2010. Recall that

Westphalian sovereignty is, in Krasner’s 1999 account, the principle that “states

have the right to exclude external authority from their own territory.” Westphalian

sovereignty is to be contrasted with international legal sovereignty, the principle that

“international recognition should be accorded only to juridically independent

sovereign states.”

6

7

catastrophes of the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) came to an end.

The reverse side of Hobbes’s intellectual achievement, however,

was that no larger notion of sovereignty was left on the table. Neither

any notion of divine sovereignty nor of social sovereignty nor of

individual sovereignty could compete with the absolute political

sovereignty that Hobbes so magisterially laid out against the

backgrounds of his bleak views on human nature in his 1651

masterpiece, Leviathan.7 Only later, when John Locke brought back

into discussion, mainly in his 1689 Essay Concerning Human

Understanding, some of the previously banished connections between

politics and religion, was there a new move set on foot to recapture

some of the earlier breadth of vision that the pre-Hobbesian uses of

sovereignty had already included.8

Besides this idea of the importance of an inclusive understanding

of sovereignty that that the composite account emphasizes, a second

key idea about individual sovereignty in this account also deserves

special attention. That idea is a suggested distinction between hard

and soft versions of self-sovereignty.

Since Augustine’s debates with the Pelagians about whether

human beings could take the first steps towards salvation without

God’s grace, what may be called hard self-sovereignty can be

understood in terms of power. On this view, the self is both “legislator

and enforcer: the self is a kind of law unto itself, taking the form of a

faux categorical imperative, faux in the sense that one could not

See especially N. Malcolm’s Introduction to his recently published three volume

edition of Leviathan in Hobbes 2013.

7

Cf. Locke 1979 and the discussion for example in Wolterstorff 1995, pp. 261-280.

Note that Locke’s larger discussion is in the Essay and not in either the Two

Treatises on Government and the Letter on Toleration, both published also in 1689

but anonymously. For critical discussion of those texts see Rawls 2007, pp. 103-155.

8

8

coherently will that there be no daylight between one’s own will and

universal willing” (p. 172). Thus, the hard version of self-sovereignty is

all about “power, self-encoded, enacted whenever the self sees fit”

(Ibid.). Hard sovereignty is the sovereignty of the Pelagian individual.

By contrast, the soft version of self-sovereignty is all about

relaxing or repudiating “any standards on, or for, the self” (p. 173). On

this version of self-sovereignty, the soft sovereign self “ongoingly

affirms itself, validates itself . . . [for] the only valid rules are those I

make for myself” (Ibid.). Soft sovereignty is the sovereignty of the

Augustinian person.

What is especially important about this distinction between hard

and soft self-sovereignty for our concerns with trying to win a fuller

understanding of necessarily limited individual sovereignties is the

realization that neither of these kinds of self-sovereignty is

satisfactory. For the hard version of self-sovereignty, with its

commitment to the absolute autonomy of the self, rules out any

genuine community of personal sovereignties. And the soft version of

self-sovereignty, with its commitment to the exaggerated fluidity of the

self, leads to the loss of any proper critical distance from community.

On this composite account, then, “each features a monistic,

voluntaristic notion of the self, the self ‘as one’ with its projects” (p.

204). If hard sovereign selves stand alone, soft sovereign selves “are

absorbed in a collective or group project” (Ibid.).

Thus, this composite account of self-sovereignty, or of what we

are calling here individual sovereignty, comprises at least two key

notions. The first is the idea that individual sovereignty must be

properly inclusive, and the second is the idea that properly inclusive

individual sovereignty must be neither a hard nor a soft self-

9

sovereignty. Rather, a properly inclusive individual sovereignty must be

open to the transcendence of both the state and society, of both

political and social sovereignties.

Individual sovereignty, in short, must finally be construed in such

terms that the relations between transcendence and immanence

determine its proper limitations.

14.2 Immanence and Transcendance

One persisting problem with these two key elements of the

composite account of individual sovereignties is the unresolved

tension between the individual’s necessary participation in a political

and social world and the individual’s necessary critical distance form

any particular political or social world as such.

The participation is necessary in the sense that part of what it

means to be a human being is to be socially and politically part of a

larger whole. And the critical distance is necessary in the sense that

part of what it also means to be a human being is to exercise the

capacities of self-consciousness in such ways as to remain irreducible

to one’s political and social world. Or, in the familiar religious idiom on

which this composite account often relies, one must, so to speak, be in

the world but not of it.

How then can we reconcile this double necessity, the necessity

of belonging and the necessity of critical distancing?

On several of the terms of this composite account, individual

sovereignty is properly a matter of making room for transcendence in

the midst of immanence. Making some sense here of that distinction

will be fruitful for making still more specific our intuition that individual

sovereignties, like political and social ones (even if not “just like”

10

them), are necessarily limited sovereignties.

Transcendence on the composite account comes into discussion

when one takes a close look at the nature of the absolute monarchy

during the French Revolution. For the theorists of the time, the

absolute monarch was the intermediary between the two realms of the

worldly and the other-worldly, of the immanent and the transcendent.

Indeed, the task of the French revolutionaries, as they themselves

understood it, was “dethroning the semi-sacred body of the one – the

king – the living mediator between heaven and earth, the transcendent

and the immanent – and rethroning [sic], via a ‘religion of reason’ a

collective sacral body, le people, the people, the general will to which

all must pledge ‘Amen’ without reservation” (pp. 141-142).9

On this composite account, the revolutionary program of radically

replacing an individual royal person (the king) with a collective person

(the people) as the intermediary between the transcendent and the

immanent had two central consequences. Together, these two

consequences resulted in changing radically many of the previous

understandings of both the transcendent and the immanent.

Thus, for one, the transcendent lost its consistency. The

transcendent became “remote, gauzy, dematerialized, a vague ‘beyond’

but, in reality, presentist and based on a particular manifestation of the

self” (p. 142). Conversely, the immanent became more substantive. The

immanent, “rather than emerging chastened from the experience of

‘revolutionary virtue’ and less tempted toward sovereign excess and

grandiosity, goes in the other direction and sacralizes a finite set of

temporal arrangements” (Ibid.).

The general outcome of these two consequences was promotion

Note that this in fact controversial reading in the composite account of sovereignty

of one of the main tasks of the French Revolution is Camus’s interpretation in his The

Rebel which Bethge Elshtain cites at some length. See Camus 1956, pp. 106-122.

9

11

of the immanent at the expense of the transcendent at both the

political and the individual levels. “Denial of the transcendent and a

correlative divinizing of the experiences of ‘self’ or the state,” Bethge

Elshtain writes in summary, “fuels a self driven to certain sorts of

extreme ‘on the edge’ experiences as a way to feel wonder and awe,

and a state driven to a form of ‘overcoming’ or transcendence that

courts triumphalism: there are markers of monism, even nihilism”

(Ibid.).

14.3 Evaluating the Composite Account of Sovereignty

There is much that is helpful in this composite account of

individual self-sovereignty. The retrieval of the quite important

medieval backgrounds to the major elaboration of the key notion of

sovereignty today in the seventeenth century as well as the careful

reminders of the relations between politics and religion in some of the

central writings of the Reformers are significant correctives to what

can often be a rather blinkered or overly abbreviated reading of the

origins of modern understandings of sovereignty.

Moreover, as we have seen, the composite account of individual

self-sovereignty usefully reminds us of several crucial distinctions in

trying to understand sovereignty better. The distinctions are between

inclusive and exclusive sovereignties, between hard and soft

sovereignties, and between the vertical sovereignties of

transcendence and the horizontal ones of immanence.

Nonetheless, at least three critical points suggest the need for

still further reflection about the nature of individual sovereignties as

necessarily limited sovereignties.

The first critical point concerns the pertinence of the exclusive-

12

inclusive distinction with respect to individual sovereignties in

particular. Admittedly, this distinction applies in a fruitful way to our

understandings today of political and even social sovereignties. Still,

its application to the quite different domain of individual sovereignties

is not so evident. For in this domain, unlike in the other two domains,

whether one can speak properly of the exclusive and the inclusive is

questionable.

Thus, rather than speaking about how individual sovereignty can

be exclusive of other sovereignties such as the political or the social,

perhaps we do better to speak of individual sovereignties not in terms

of exclusive and inclusive but in those of internal and external. Thus,

political and social sovereignties arguably are better understood as

being external to individual sovereignties rather than individual

sovereignties being such as to exclude political and social

sovereignties.

A second critical point arises with respect to the usefulness of

the distinction between hard and soft individual sovereignties. For it is

not evident what gains we may realize in terms of better understanding

the necessary limits of individual sovereignties by talking freshly of

hard and soft individual sovereignties instead of continuing to talk

about absolute and relative individual sovereignties. The second,

traditional distinction, for example, arguably renders more service than

the more contemporary one in this composite account between hard

and soft individual sovereignties. This is especially the case when we

try to account for some of the causal mechanisms that mainly bring

about the negative consequences of any exaggerated individual

sovereignties.

And a third critical point, the most important one, concerns the

central distinction in this composite account between the

transcendent and the immanent. This distinction, unlike perhaps the

13

other two, is certainly pertinent to our concerns with understanding

the necessary limitations of individual sovereignty. For it captures a

dimension that the previous accounts of political and social

sovereignty have, perhaps for good enough reasons, underplayed. That

underlying and very important distinction is between the political and

the religious. And as we have noted one of the strengths of the

composite account is its emphasis on the major significance of the

religious. For it is the religious that brings into critical discussion the

ineluctable human tensions between the immanent and the

transcendent.

On reflection, however, what seems still lacking in the composite

discussion of immanence and transcendence is a higher resolution in

the analyses of each of the two central terms.10 That is, if we are to

understand better the limitations of individual sovereignty, then we

need to refine our understanding of both the immanent as such and the

transcendent as such. Restricting our account just to their roles as

correlatives if we have not provided independent account of each of

these notions in particular is insufficient.

There are of course different basic types of transcendence and

different basic types of immanence. Moreover, not all of these different

types can be properly paired as correlatives. Still more, the roles of

these different and polymorphic concepts differ appreciably depending,

to take but one of several factors, for instance on the particular

domains in which we are employing them. Thus, the immanent in the

domain of issues arising in the philosophy of art is not necessarily the

same at all as the immanent in the domain of metaphysics. Similarly,

the transcendent in the domain of the philosophy of religion is not

necessarily the same at all as the transcendent in the domain of social

epistemology.

10

See for example the entry on “transcendence” in Honderich 2005.

14

In our continuing inquiries then into the necessity of limited

individual sovereignties we will need to be more careful about

specifying our particular domains of inquiry. Morover, we will need to

take note of some important non-correlations between various senses

of transcendence and immanence than seem to be the case in the

composite account of self-sovereignty we have looked at here briefly.

Concluding Remarks

Among many other virtues, the composite account of selfsovereignty is rich in history and in distinctions. After noting those

virtues and, in addition, having noted as well several critical points

that must be kept in mind, we may now find it useful to take up still

another and here final excursus into the Aegean Bronze Age cultures

where so many of our central cultural notions today first took their

very tentative forms.

Specifically, we will now look at the earliest proto-European

culture in the Aegean Bronze Age, namely the Cycladic culture. Our

concern will be to retrieve if we can, with both sufficient historical and

conceptual care, several almost forgotten insights into the nature in

particular of individual sovereignties as necessarily limited.

§15. Cycladic Europe: the Marble Lady of Naxos

Following on our considerations of symbolic golden embossed

funerary masks dating from the closing centuries of the Late Helladic

Bronze Age on the Greek mainland, and on our reflections on a

symbolic Minoan male statuette dating from the Middle Aegean Bronze

Age on Crete, we now turn still farther back. Here we take up the

appearance in the Early Aegean Bronze Age (ca. 3200-2000 BCE) of the

15

familiar symbolic white marble female figurines dating from the first

permanent settlements in the Cycladic islands of the Aegean Sea.

15.1 Early Cycladic Marble Figurines

Archeologists and ancient historians tell us, cautiously, that the

singular culture if not civilization in the Greek Aegean of what

Herodotus called the Cyclades

11

begins with the first Neolithic

permanent settlement known there so far.12 This culture appears

roughly at the middle of the fifth millennium BCE.i The Greek mainland

backgrounds to the Cycladic figurines are to be found in the Middle

Neolithic (ca. 5800-5300) ii double figurines from Thessaly.13

Archeological excavations on the tiny islet of Saliagos in the

straits between the Cycladic islands of Antiparos and Paros have

uncovered evidence for a much later communally organized permanent

settlement in the collectively constructed defensive works and in the

several stone houses these works enclose.14 Other later sites

exhibiting features of the same Saliagos culture have also been found

elsewhere in the Cyclades, notably on Naxos, Mykonos, and Thera.15

By the end of the so-called “Keros-Syros Phase” of Cycladic

For a recent overview of early Cycladic culture see Bintliff 2012, pp. 102-122. The

reference for Herodotus is to his Histories, V, 31.

11

12

Doumas 2000, p. 18. For the Late Neolithic see Tomkins 2010, esp; pp. 39-42.

13

See the drawings in Figure 3.10 in Bintliff 2012, p. 75.

Cf. Evans and Renfrew 1968. See however Doumas 2000, pp. 36-37 on the

significance of the defensive works that appear suddenly at this time.

14

For the Cyclades in the Early Bronze Age see Renfrew 2010, esp. pp. 86-90, Barber

2010a, pp. 128-129, Barber 2010b, pp. 162-166. Cf. Broodbank 2008 and Davis 2001.

15

16

culture in the transitions between the Early Cycladic II and III periods

ca. 2300 BCE,iii a great decline occurs in the carving of these white

marble figurines. They are succeeded by much less artistically realized

schematic figurines and “the solid, soulless forms which confirm the

poverty of the period.”

16

Many scholars currently understand the Late Neolithic Saliagos

settlement as, among other things, a center for preparing the much

prized obsidian, a black, sharp, volcanic, glassy stone, for export and

distribution to many earlier Neolithic permanent settlements on the

Greek mainland.17 There, mainlanders would further work the obsidian

into cutting devices not just for butchering but also for carving marble,

which is a white, soft, crystalline stone.

As imported obsidian remains from the Franchthi cave in the

Argolid and other evidence demonstrate,18 however, long before the

founding of the Saliagos settlement some Neolithic mainlanders were

already braving the seas to visit the Cyclades from roughly 8000-7000

BCE onwards.19 They continued to do so for the next several thousand

years. But only with the later development of more reliable boats and

seafaring skills

20

of the late Neolithic could mainlanders establish

permanent settlements on Saliagos and on other islands in the

16

Doumas 2000, p. 36.

17

See Shackley 1998.

Cf. Jacobsen 1981. For the Franchthi Cave see Bintliff 2012, pp. 33-37; cf. Pullen

2008, pp. 20-21.

18

19

Cf. Strasser et al. 2010.

Cf. Broodbank 2000. The citation from Sikelianos at the beginning of Part Three is

anachronistic here since boats with sails appeared later than the figurines we are

examining. Still, the poem may give a sense of the sensations of early mariners.

20

17

Cyclades such as on Melos for more obsidian and on Naxos for emery.21

With these settlements the elements for the emergence of one of

the most singular manifestations of Cycladic culture generally were in

place.

iv

“With obsidian,” as one specialist has written, “the prehistoric

islanders could cut the soft marble into shapes.”

22

And with emery

they then could “polish and smooth [the] marble without leaving behind

any scuffs or colors,” thus imparting to the soft marble “the soft patina

of the stones on the shore.”

23

This innovative technology made

possible, among other inventions, the creation of the early Cycladic

distinctive artifacts first discovered at the end of the nineteenth

century and now called Cycladic figurines.24

Before, however, trying to discuss the cultural meanings of

several of the most representative of these artifacts, specifying their

nature and their provenance is a priority.25 Indeed, to be thorough, one

would need “to record the location and number of found figurines, the

other objects they are found with, their depositional histories, how

they were made and later broken, the history of their existence, and

their use life from the moment they were formed, through the many

uses and reuses, to their recycling and eventual discard.”

26

Also,

originally many of these figurines displayed tattoos, 27 painted

21

22

23

Broodbank 2008, p. 51.

McGilchrist 2012, p. 31.

Ibid. On marble-carving in the Cyclades see Doumas 2000, pp. 42-43.

See Renfrew’s 1972 typology of figurines reproduced in Bintliff 2012, p. 115. Cf.

Doumas’s later and somewhat different typology in Doumas 2000, pp. 44-45.

24

“few have been recovered from their original context of deposition rather than via

the antiquities market; there is no clear guide to their function” (Bintliff 2012, p. 113).

25

26

Tsonou-Herbst 2010, p. 219.

27

Broodbank 2008, pp. 48-49;

18

features,v and jewelry.

Here, we must settle for something much more modest.

15.2 Nature and Provenance

During the third millennium BCE

28

almost 2000 figurines are now

known to have been produced in the Aegean areas.vi Figurines are

“small-scale representations of humans, animals, and objects,” the

same specialist writes, “that were regularly produced throughout the

Bronze Age in the Aegean, continuing an extant tradition from the

Neolithic period.”

29

Cycladic and Minoan figurines continue to appear after the end of

the Early Aegean Bronze Age. By contrast “the mainland tradition of

female figurines with exaggerated body features dies out in the Early

Bronze Age.” It is important to remember, however, that the production

of figurines has its high point in the Early Aegean Bronze Age and then

declines afterwards in the Middle Aegean Bronze Age while at the

same time their production increases dramatically in Crete.30

Figurines are handmade, small (between 0.05 and 0.20 m. in

height), rather numerous, and found mainly in cemetery graves and

sometimes in the households of settlements. Materials vary but most

early figurines are made of clay and a good number are also made of

white marble. In some cases details of the early marble figurines are

highlighted in bright colors.31

28

Cf. Renfrew 1972.

29

Ibid., p. 211.

30

Ibid., p. 215.

31

Ibid., p. 211. Cf. Hendrix 2003.

19

In these respects figurines are unlike figures. Figures are larger

than figurines; they are between 0.35 to 0.69 m. They are also rarer -only 43 late Minoan and 17 Mycenaean figures are currently known.

Figures, for example the “Palaikastro Kouros,” are similar to small

statues. Figures thus are statuettes. Further, figures are wheel made.

Moreover, they are found perhaps exclusively in sanctuaries and ritual

sites like the ritual site where the “Palaiskatro Kouros” was found.

Well-documented examples are from the excavations at the Phylakopi

32

settlement on the Cycladic island of Melos and from the so-called

“Keros Hoard” under excavation since the 1950s.33

Figurines from the “Keros Hoard” are notoriously difficult to study

because grave robbers in the 1960s devastated the site where very

many fragmented objects were found. They destroyed the architectural

contexts, and then flooded the antiquities markets with the stolen

goods as well as with fake figurines.34 Although there is as yet no

scholarly consensus regarding the functions of these specific figurines,

whether strictly ritual or not, they have been found mainly in

cemeteries and settlements. Ongoing excavations on Keros are partly

designed to provide much needed further information on this point.

Archeologists have found many figurines (“up to fourteen”) in

individual tombs with the burial. And “both male and female figurines

are interred with many valuable grave goods or none at all. [But] they

are not equally common in all islands.”

35

The spatial distributions, chronologies, and typologies of the

32

Renfrew 2010, pp. 89-90; cf. Renfrew 1985, Whitelaw 2004, and Renfrew 2007.

33

Cf. Renfrew 1985 and Sotirakopoulou 2008.

34

Doumas 2000, p. 30; Broodbank 2008, p. 50.

35

Tsonou-Herbst 2010, p. 214.

20

early white marble figurines are complicated and controversial. 36 We

will thus find it useful here to narrow our focus to one distinctive type

only of the in fact quite various Cycladic white marble female figurines.

This type is the more anatomically detailed, so-called “Folded-Arm

Figurines” which replace the still earlier schematic figurines. In

particular, we will focus on the slender, Folded-Arm Figurines,vii

standing “on tiptoe with the head tilted back and the arms folded over

the stomach” of the Spedos variety.37

Perhaps one of the most important of these figurines is the

female figurine, one of the so-called “canonical” figurines attributed to

a supposedly distinctive styleviii of “the Goulandris Master,”

38

on view

in the N. P. Goulandris Foundation Collection in the Museum of

Cycladic Art in Athens.ix

15.3 A Description of a Canonical Folded-Arm Figurine

Here is the catalogue description of this piece.

“214. Female figurine

“White marble. Chipped on the shoulders and head.

H. 63.4.

Provenance unknown [possibly southern Naxos].

Coll. no. 281.”

“Lyre-shaped head with large conical nose and pointed chin. Markedly

sloping shoulders. The arms and small breasts are rendered in relief.

36

The pioneering work is that of Renfrew 1965, 1985.

37

Ibid., p. 211.

Cf. Getz-Gentle 2001. Note that attributions to individual “masters” on the basis of

unique individual artistic styles while “persuasive” remain controversial. See Renfrew

and Bahn 2012, p. 413.

38

21

Slightly concave incisions demarcate the neck and the limbs from the

trunk and emphasize the joints of the knees and ankles. Incisions

indicate the fingers and shallow grooves the toes. The limbs are

distinguished by a shallow cleft and flex slightly at the knees. Traces of

pigment preserved on the chest and the back of the head, where it

evidently coated the coiffure: a curved band runs down from the right

shoulder to the right forearm, two diagonal bands down the head and

neck at the base of which they separate and terminate in two curls,

each reaching low down on the back.”

“Canonical type, [late?] Spedos variety. The largest known intact work

attributed to the ‘Goulandris Master.’”

39

15.4 Another Folded-Arm Figurine

For comparison and contrast here is another catalogue

description of a similar figurine.

“178. Female figurine

White marble. Badly eroded on the face and right thigh. Pale

incrustation in places. H. 47.2. Provenance unknown. Coll. no. 311. Lyreshaped head with forehead tilted backwards. The arms and breasts are

in low relief. The modeling of the top of the thighs also defines the

pubes. The legs are flexed at the knees and the calves separated, while

the fingers and toes are incised. The figure is distinguished by its

relative slenderness, its curvaceous profiles and the rounded modeling

mainly on the arms and abdomen.

Canonical type, one of the large-scale works of the early Spedos

variety.”

40

§16. Cultural Meanings

39

Doumas 2000, p. 147 and Fig. 214 ; cf. Getz-Preziosi 1987, p. 160, note 27.

40

Doumas 2000, p. 133.

22

With these general contexts in mind and with these catalogue

descriptions if not the actual figurines before us, we may take up the

question of the cultural meaningfulness of such figurines.

16.1 Cultural Meanings

We have already discussed briefly in the previous seminars some

of the general definitional problems concerning the very idea of culture

and cultural meanings. There are, moreover, a host of related

interpretive issues that cluster around the cultural meanings of

symbolic, ritual artworks in particular.41 Here, however, we need only

recall that ancient historians and archeologists approach such

artifacts almost invariably with a particular set of interests and

concerns.

Thus, with respect to the early Cycladic figurines in particular,

“scholars have searched for interpretations based on certain criteria,

and then they [have] questioned whether the archeological record

preserves any clue to help uncover the meaning figurines had for their

makers and owners.”

42

But, while not uninformative, the results have unfortunately been

meager. Indeed, so far are specialists today from reaching any

consensus about the cultural meanings of these enigmatic figurines,

that even after years of excavation and study the best known of these

specialists and one of the world’s greatest living archeologists has

declared: “We do not know, and we shall probably never know, quite

why they were made.”

43

41

See Renfrew and Bahn 2012, pp. 410-416, and Insoll 2011.

42

Tsounou-Herbst 2010, p. 210.

43

Cf. Renfrew 2003, p. 77; cited in Tsounou-Herbst 2010, p. 2010.

23

Even if, as here, we restrict ourselves very greatly just to Female

Folded-Arm Figurines of the canonical types of “The Goulandris

Master” of the late Spedos variety in the Syros Phase towards the end

of the Early Cycladic II Period (2800-2300 BCE), we still must ask many

questions.

Were these figurines made “simply and solely to be ‘good to look

at’” as Renfrew himself has suggested?

44

Was there an important

functional difference between the figurines made of clay and those

made of white marble? Or were they ritual objects to be used at

sanctuaries? Or were they funerary artifacts to be buried with the

deceased? Or were they elite household luxury items? Or, since some

were found near tomb burials of children, were they just made as

educational objects, or even as toys?

Or did their functions vary, and not just from one site to another

but from one time period to another? Or even within a particular

setting, were their functional transformations the same during their

use lives, as in the case of many much later Minoan and Mycenaean

figurines? Why are some figurines apparently unique pieces and others

figurines in a stylistic series?

Or were they made as religious representations? Were they

meant as votive offerings? Or were they household shrine objects?

Were they primarily individual or community possessions? And why

were some buried respectfully and others discarded in trash deposits?

Unlike the meaningfulness then of figures like the Palaikastro

Kouros, the cultural meanings of at least figurines like those of “The

Goulandris Master” that we have focused on here were apparently

44

Ibid.

24

much more various.45

The archeological contexts in which archeologists have

unearthed these figurines and the assemblages in which they have

been found are indeed many and varied. That remains the case even

when we restrict our considerations to those archeological contexts in

the Cyclades only, specifically during the Syros Phase,46 and leave out

of account the Early Helladic mainland sites, the Early Minoan sites,

and the still later Bronze Age Aegean sites where similar figurines with

apparently different functions have been found.

None of the Cycladic sites, however, whether taken alone or

together, allow of any definitive assignments of the functions of even

this very narrowly selected subgroup of figurines to any one particular

sphere of human activity. Their cultural meanings would seem to be

almost as various and multiple as the sites in which they have been

found so far. And even such sites where still further discoveries are

being made, as in the Dhaskalio Kavos site on Keros where

excavations are still continuing,47 have yet to provide sufficient

materials to answer these questions satisfactorily.

16.2 Religious Contexts

Still, even our quite limited probings in the vast literature

disclose roughly four main approaches to the cultural meaningfulness

45

Ibid., p. 217.

“The very wide distribution of the shapes of the Syros phase illustrates that a

single Cycladic Culture prevailed throughout the archipelago. . . .” (Doumas 2000, p.

35. Doumas divides the Early Cycladic Period (2800-2300 BCE) into first the Kampos

phase and then into the longer Syros phase (p. 20).

46

47

Cf. Renfrew 2006, Whitley 2007.

25

of the finest of these pieces. Thus, the majority of specialists in

Aegean archeology today are willing to grant that the great number of

religious contexts in which they have been unearthed does not exhaust

the cultural meaningfulness of the Cycladic figurines. Nonetheless,

they seem to hold that the religious accounts for most of the cultural

meanings of such figurines.48

Others, however, have noted that the religious contexts often

provide much information not just about cult practices and sanctuary

arcana. These religious contexts also provide information about the

groups of people who were the actual users of these figurines.

Accordingly, this second group of archeologists, the minority, believes

that the major cultural meanings here are to be understood more as a

function of mainly ethnic identities rather than of mainly religious

importance.

Other archeologists have called fresh attention in particular to

the archeological contexts in which these figurines have been found.

“The find contexts,” one specialist has written recently, “show that

figurines had a varied existence. They were not religious artifacts for

all people at all times. Some considered them religious if or when they

had been made efficacious through ritual. Others recycled, reused, or

threw them in the trash.”

49

And still another group of archeologists has called attention to

the presence of what they call “a priori assumptions” that lie behind

the almost exclusively religious or almost exclusively ethnic

interpretive approaches. To avoid such methodological pitfalls, these

archeologists hold that less problematic interpretive approaches

should start from the idea that other alternatives must be sought out.

48

See Whitehouse and Laidlow 2007.

49

Tzonou-Herbst 2010, p. 219.

26

“To be able to produce these,” perhaps their most important

advocate writes, “we need to record the location and number of found

figurines, the other objects they are found with, their depositional

histories, how they were made and later [often deliberately] broken,

the history of their existence, and their use life from the moment they

were formed, through their many uses and reuses, to their recycling

and eventual discard. We can then infer the lifestyle of figurine

owners.”

50

16.3 Meanings: The Philosophical versus the Cultural?

Some have pursued this critical approach further. “Inevitably,”

one archeologist writes, “archeological interpretation consists of

facts, but it also depends on the imagination and speculation of the

archeologist. The multiple interpretations produced for figurines

demonstrate that. Figurines are enigmatic and will continue to puzzle

us. They have their own idiosyncratic characteristics since they are

creations of landscapes, times, and people that no longer exist. We

attempt to revive their worldview, thoughts, and perceptions as they

portrayed them in these objects.”51

When such an approach is adopted, what then is the outcome?

The basic outcome, the claim here runs, is that figurines are to be

understood as properly supporting no one interpretation; rather,

figurines are to be understood as supporting multiple interpretations.

Two reasons are adduced for this outcome. First, multiple

interpretations are to be sought rather than any one interpretation

These are the methodological principles that I. Tzonou-Herbst makes explicit in

2010, p. 209.

50

51

Tsonou-Herbst 2010, p. 2010.

27

because the cultural meaningfulness of these figurines is “fluid and

variable.” 52 And, second, multiple interpretations are to be sought

because, necessarily, archeologists read into the socio-cultural

environments that these figurines create by themselves producing

“meanings according to their own perceptions and interests.”

53

The result is that there must be many cultural meanings of Early

Cycladic figurines. How so? Because “their meaning or meaningfulness

is “fluid and variable and because archeologists construct those

interpretations, which reflect their readings of the sociocultural

environment that created the figurines. Archeologists produce

meanings according to their own perceptions and interests.”

54

One of the most recent of these interpretive approaches that

would seem to espouse such multiplicity while notably taking many

pains to anchor any particular interpretation strongly on evident

empirical evidence runs as follows.

“. . . one reasonable hypothesis would suggest that

Cycladic figurines could represent both real people, as

nodes of social interaction, and divine forces as nodes of

society’s ritual interaction. In the absence of a system of

genuinely large communities acting as a focus for individual

islands, or as centers for a much larger scale of sociability

between several islands, we may be seeing instead an

exaggerated emphasis on chains of smaller-scale

interactions: these would revolve around communal meals,

voyages, marriages, burials, festivals, and acts of group

52

Ibid., p. 220.

53

Ibid.

54

Ibid., p. 220.

28

worship. . . .”

55

With these remarks in place on the varied cultural

meaningfulness of such figurines as the Goulandris Master piece and

on their apparently necessary multiple interpretations, we now need to

draw a last series of interim conclusions about sovereignties, this time

about the nature of individual sovereignties. These interim

conclusions, when added to the previous two sets, will then set us the

task in our final section on “Re-Orientations” to make several direct

connections with renewed discussion of different kinds of sovereignty

today in the EU.

We will find that in addition to our concerns with the political

values of order and eventually the rule of law arising from reflections

on several salient artworks of the Mycenaean origins of European

civilization, and the social values of rankings and eventually of

pluralisms arising from reflections on several artworks of the Minoan

origins of European civilization, something further needs consideration.

For an historically representative preamble to any eventual EU

constitution would also do well to make room for incorporating the

moral and political individual values of proportions and eventually

dignity. And these values may be seen as arising from reflections on

several salient features of the Cycladic origins of European civilization

today.

§17. Philosophical Significance (TBA)

17.1

55

Bintliff 2012, p. 116; see also pp. 74-77.

29

17.2

17.3

Discussion of Seminar Three §17 and Concluding

Remarks

§18. A Third Set of Interim Conclusions III:

Bounded Sovereignties

Once again a short case study of the archeological findings of the

canonical Cycladic figurines from the zenith of the Early Cycladic

period when the Cycladic Culture had spread throughout the

archipelago at the beginnings of European civilization in the Aegean

Bronze Age suggests for critical discussion three major points about

the nature of individual sovereignties.

18.1 Individual sovereignties are limited with respect to other

individual sovereignties that exist within the same political and social

realm.

18.2 Individual sovereignties are also limited with respect to

individual sovereignties that exist beyond their own political and social

realm in other, quite different political and social realms.

18.3 Individual sovereignties are limited still more with respect

to their subordination to the norms, values, and ideals of religious and

spiritual realms.

After our investigations then of the limited nature at the outset of

European civilization of both political sovereignties at the apogee of

30

Mycenaean culture, social sovereignties at a highpoint of Minoan

culture, and individual sovereignties at the zenith of Cycladic culture,

we need now to bring our historical inquiries to a conclusion by turning

to the philosophical significance of these disparate but related cultural

meanings.

Endnotes

Again with simplifications and adaptations, and as above in Chapter

One for the Mycenaean Civilization and in Chapter Five for the Minoan

Civilization, I use here for the Cyclades Bintliff’s 2012, p. 46 calibrated

Carbon 14 dated chronologies and abbreviations as follows (dates give

the approximate beginnings of the BCE periods):

i

7000: Pre-Ceramic Greek Neolithic

6500:

5800:

5300:

4800:

4500:

EN, or early phase of Neolithic with generalized uses of ceramics

MN, or middle phase of Neolithic

E-LN, or early-late phase of Neolithic

L-LN, or later-late phase of Neolithic

FN, or final phase of Neolithic

32OO: EBA, or Early Bronze Age

These figurines are “predominantly female, and are relatively

abundant in the Greek (and Balkan) Neolithic, with clear Near Eastern

parallels. However, little can be said about their meaning in any of

these contexts. The natural tendency has been to read the female

class (Figure 3.10) either as a goddess or a series of goddesses, or as

ancestors (in a female-oriented kinship system or matriliny), or, given

the ample proportions of most, as symbolic representations of (female

or general) fertility, which can then be extended to animals whose

fertility is also welcome” . . . Most recently several commentators

suggest that the meaning of figurines depended more on their context,

such as their deployment in different phases of human life or in the

ii

31

circulation of the objects themselves. It is very unhelpful that their

occurrence in Greek Neolithic burials is little known about, due to the

poverty of such contexts; since the successor figurines from the FNEBA in Southern Greece occur frequently in formal cemeteries, and are

then considered as likely to have religious associations” (Bintliff 2012,

pp. 74-75).

To the Bintliff’s general scheme in endnote ix above should be added

the more particular chronologies for Early Cycladic culture from

Doumas 2000, p. 20 with period, phase, and presence on the islands

indicated as below with small changes. The highpoint is the Early

Cycladic II period from 2800-2300. “The florescence of the Cycladic

Bronze Age art . . . is in the ECI-II period of the third millennium BCE

(Grotta-Pelos and Keros-Syros phases” (Bintliff 2012, p. 114).

iii

[4800: LN as above] / presence on: Antiparos, Thera, Mykonos, Naxos

4500: FN / Kea

3200-2800: Early Cycladic EC I / Successive Phases:

Lakkoudes Phase on Naxos;

[Grotta-] Pelos Phase on Antiparos, Despotikon, Thera, Melos, Naxos,

Paros, Siphnos; and

Plastiras Phase on Antiparos, Despotikon, Thera, Kea, and Paros

2800-2300: EC II /

Kampos Phase on Amorgos, Antiparos, Despotikon, Thera, Koufonisia,

Naxos, and Paros;

[Keros-] Syros Phase on Amorgos, Despotikon, Delos, Thera, Kea, Keros,

Naxos, Paros, Siphnos, Syros, Christiana

2300-2000: EC III /

Phylakapi I on Thera, Kea, Melos, Naxos, and Paros

2000: Middle Cycladic MC / Thera, Kea, Melos, Naxos, and Paros

“The very beginning of generalized settlement on the Cyclades, with

the late Neolithic Saliagos culture, is already associated with marble

figurines . . . but they belong to the Neolithic Greek and Near Eastern

style. In the following Final Neolithic, at Kephala on Kea, both ceramic

iv

32

figurines and marble vessels show the development of characteristic

Early Cycladic styles, and the formal cemetery here also introduces

the Cycladic form of burials. However the florescence of Cycladic

Bronze Age art . . . is in the EC1-2 periods of the third millennium BCE

(Grotta-Pelos and Keros-Syros phases).

The commonest figurine appears on analysis to be female; with

folded arms, and naked, with a highly schematic appearance. It

appears throughout the islands and on their margins, such as parts of

the Eastern Greek Mainland and in Early Minoan Crete. . . . from the

minute study of the corpus of figurines . . . nearly all seem to have

been painted. . . . It can be suggested that the canonical

‘undifferentiated human,’ till recently forming the accepted reading of

the figurines now appears to be a distinctive individual, very much

affecting the possible meaning of such objects” (Bintliff 2012, p. 114).

There is a realization “from the minute study of the corpus of figurines

[by “ultraviolet reflectography and computer enhancement”: Broodbank

2008, p. 49], that nearly all have been painted. Although the aim was to

highlight detail, the effect dramatically alters their appearance with

hair and eye color and painted designs on the face (resembling

warpaint or tattoos rather than makeup, to my eyes). It can be

suggested that the canonical ‘undifferentiated human,’ till recently

forming the accepted reading of the figurines now appears to be a

distinctive individual, very much affecting the possible meaning of

such objects” (Bintliff 2012, p. 114).

v

Major collections are to be found in the Goulandris Collection of the

Museum of Cycladic Art in Athens (see Renfrew 1991 and Doumas

2010), in the Getty Museum collection in Los Angeles (cf. Getz-Gentle

1995), and in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford (cf. Sherratt 2000)

based on the early collections of Sir Arthur Evans. Cf. collections also

in the Louvre in Paris and the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

vi

x

???

Specifically, this type of figurine is called the Early Cycladic II “white

marble figurine, Late Spedos variety.” See Tsonou-Herbst 2010, Figure

vii

33

16.1 (2), p. 212. This type of figurine corresponds roughly (excepting its

lyre-like head shape) to Renfrew’s 1972 IV.A figurine from the KerosSyros period reproduced in Bintliff 2012, p. 115, Figure 4.12.

“When talking of ‘style,’ Renfrew and Bahn 2012 remark, “we must

separate the style of a culture and period from the (usually) much more

closely defined style of an individual worker within that period. We

need to show, therefore, how the works that are recognizable in that

larger group (e.g. the Attic black-figure style [in the classic

categorizing work of J. Beazley in the mid-twentieth century]) divide on

closer examination into smaller well-defined groups. Moreover, we

need to bear in mind that these smaller subgroupings might relate not

to individual artists but to different time periods in the development of

the style, or to different subregions (i. e. the local substyles). Or they

might relate to workshops rather than to single artists” (p. 412). The

attempt to assign individual figurines to individual “masters” was

pioneered by Getz-Preziosi 1987. Related closely to the figurines

attributed to the Goulandris Master are those of the late Spedos

variety attributed to the so-called “Naxos Museum Master.” Other

masters are “The Copenhagen Master,” named because of a group of

stylistically individualized figurines at the Copenhagen Museum, “The

Steiner Master,” “The Schuster Master,” and “The Ashmolean Museum

Master” at Oxford (see Doumas 2000, pp. 46-48).

viii

Doumas 2000, cat. no. 178, provenance unknown, showing front and

side views of the figurine and providing references to Renfrew 1991.

Cf. the later similar but characteristically larger figure (not figurine) in

cat. no. 222, possibly from Keros, and also of the Spedos variety, with

references to Renfrew 1986a and 1986b.

ix

Philosophers today generally prefer to use the expression

“physicalism” rather than the expression “materialism.” Already

among such Pre-Socratic philosophers as Democritus and the Greek

atomists the idea that everything is composed ultimately of matter

was current. In the twentieth century the Vienna positivists linked the

notion of materialism more precisely with modern scientific

understandings of matter. Materialism became the view that every

ix

34

existing thing simply is matter. Shortly after the middle of the

twentieth century, however, philosophers began to take over even

more precise scientific understandings of matter as ultimately forces

and energy. To capture this understanding more clearly, they went on

to use instead of the expression “materialism” the expression

“physicalism.” In what then I use the expression “physicalism”

generally as the simple view that everything in the space-time world is

physical, and particularly to denote the compound view that (a) all

mental particulars are physical particulars and that (b) all properties of

these mental particulars are physical properties. Note however that,

pace talk of forces and energy, what counts as physical remains

vague. Consequently, much continuing discussion in the philosophy of

mind concerns to how conceptually to manage such vagueness.

Envoi

(TBA)

35

![[A Trio of Seminars—Short Version: Seminar Three 8.iv.2013] A Trio](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007004909_1-ee1380b1f942c4f4804ae8ae893cec62-768x994.png)