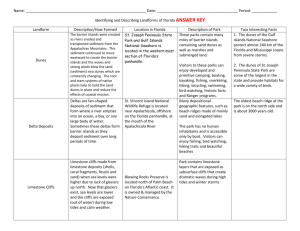

COTF Recommendations Report 10/06/2015

advertisement