Please click here - Irish Planning Institute

advertisement

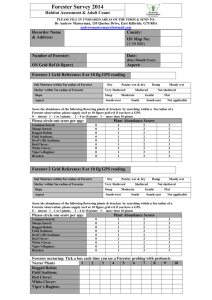

PLANNING AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT (M.PLAN), UNIVERSITY COLLEGE CORK PD6101 – Foundations in Planning and Sustainable Development Comparative Analysis of Three Core Planning Theory Readings Gregor Herda Student number 112221728 2/26/2013 This essay was produced as a continuous assessment for the module ‘Foundations in Planning and Sustainable Development’ during the first year of the MPlan programme at University College Cork. The three essays were selected by the student after consultation with the lecturer. Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 Stephen Wheeler (2011) ‘Urban Planning and Global Climate Change’ .................................... 1 John Forester (1987) – ‘Planning in the Face of Conflict’ .........................................................3 Tanja Winkler (2011) ‘Between Economic Efficacy and Social Justice: Exposing the EthicoPolitics of Planning’ ................................................................................................................... 5 Comparison................................................................................................................................9 References................................................................................................................................ 10 Introduction In the following I would like to analyse three core texts on planning theory individually and finally contrast them in terms of their relevance to contemporary planning issues. I have chosen John Forester’s ‘Planning in the Face of Conflict’ (1987), Stephen Wheeler’s ‘Urban Planning and Global Climate Change’ (2011) and Tanja Winkler’s ‘Between Economic Efficacy and Social Justice: Exposing the Ethico-Politics of Planning’ (2011). Stephen Wheeler (2011) ‘Urban Planning and Global Climate Change’ Out of these three articles I would like to begin my analysis with Stephen Wheeler’s overview of the challenge of climate change since it offers the broadest scope among the three selected texts and also outlines, in my view, the biggest challenge which planning will have to face in the coming decades. Climate change constitutes both the most dire threat to cities and at the same time the most golden opportunity for positive change. Incidentally, the same holds true for a more balanced human presence in rural settings. Likewise, failing to deal with this threat decisively and effectively would likely have enormous consequences for the observations and suggestions put forward by Forester and Winkler in their respective texts: In a post-tipping point world of rising sea levels, extended droughts and unpredictable weather patterns, Forester’s mediation and negotiation strategies would be made all the more difficult, if not impossible, as his observations are based on the assumption of a controlled, more or less ordered, environment with mainly rational (or predictably irrational) actors negotiating non-existential stakes. All these prerequisites seem very unlikely in the kind of worst-case scenario described by Wheeler. Similarly, one would have to be of a very optimistic nature to assume that the social equity and ‘moral improvement’ of individuals along Winkler’s liberal interpretation of governance will have even less relevance, if the focus of the discussion has shifted from, say, preventing litter in an urban neighbourhood to 1 existential questions of food security, forced relocation or exacerbated human health concerns. In his article Stephen Wheeler, an associate professor of landscape architecture and environmental design at the University of California, Davis, seeks to give an overview of how climate change has been dealt with on different organisational levels and as such the article does not go into great depths of pointing out specific challenges on the micro-level or claims to mention all the relevant devices applied to the task. I will therefore not try to criticise the text for not achieving something it did not set out to achieve. Wheeler states clearly that the reality of climate change and the need for mitigation and adaption are unquestionable. He goes on to roughly outline what measures governing bodies on all levels, but cities and regional authorities in particular, have taken to address both of these tasks. Turning first to mitigation, Wheeler mentions several actions undertaken by local and regional agencies in settlements as well as interventions in rural settings to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) or regenerate the planet’s natural capacity for carbon uptake. All the actors involved on these different levels address the issue of mitigation by way of either policy or direct action in ways which are within their financial or legal power. Local agencies, for instance, seek to promote bicycle and pedestrian transport, recycling, ecological education, improve standards of energy-efficiency for buildings or adopt more sustainable ways of heating and cooling those buildings. Regional agencies work to promote public transit systems and development which is in a mutually beneficial relationship to such transit as well as ensuring a compact urban form through different policy measures (local agencies can both draft and implement such policies depending on the legal framework in which they operate). In terms of interventions in the natural landscape, it is recognized that preservation of still existing natural assets will not be enough to significantly mitigate against climate change but that large-scale restoration has to take place as well. Expanding forests is as important as preserving wetlands such as peat bogs. The burning of drained peatlands, especially in developing countries with large peat reserves like Indonesia, is one of only three fire-related net sources of CO2, next to deforestation fires and fires from other areas with increased levels of disturbance (van der Wert et. al. 2010, p. 16155). The picture that emerges here is certainly one of busy optimism and one could be led to assume that averting the climate crisis is only a matter of will power and time. However, so far only the what has been mentioned, the how much is yet unknown. Wheeler (2011, p. 463) then turns to adaptation which deals with questions of how to best prepare for a changing climate. Different regions already face and will continue to face very different threats: heat waves in one region, floods and strong winds in another, rising sea levels, droughts or a combination of both in a third. Outlier events like the 2003 heat wave across Europe demonstrate the vulnerability of even developed nations in the face of increasingly unpredictable weather phenomena. However, Wheeler rightfully bemoans the fact that developing countries of the global South, that is, those least responsible for climate change, are the ones most vulnerable to the severe consequences of climate change. This is a 2 crucial issue since many adaptation measures like water conservation, flood and wind preparation or adapting to sea level rise are costly and without substantial help from developed countries, the poorer nations will have no means to adjust to their changing environment. The article’s final section deals with the social and political challenges involved (Wheeler 2011, p. 465). It states that despite the above-mentioned efforts on all governmental and organisational levels, emissions in fact increased 22 percent between 1990 and 2008. Wheeler attributes this sobering result to a lack of political will, a rising population and increasing levels of affluence in the developing world. As Wheeler points out, global life-style choices will have to be made by everybody. Especially in developing countries, this will entail sacrifices of less mobility and less consumption which may seem to many all but unthinkable. But where does this leave planning and its role in this gargantuan human task? Wheeler sees it in ‘proactively shaping social ecologies in such a way as to bring out the best potential of human beings’ (2011, p. 467). While not going into detail on what this would entail, Wheeler could be referring to helping to draft policies to promote large-scale shifts towards more sustainable development patterns or the use of different technologies, as well as implementing and enforcing these policies in an attempt to influence behaviours by changing environments. One may argue that, considering planning’s position of relative powerlessness in some countries (the United Kingdom of recent years comes to mind), that Wheeler’s view overestimates planning’s bargaining power and may be altogether too optimistic. Nevertheless, Wheeler provides a firm enough vantage point for planners from which to overlook a broad spectrum of current challenges as well as opportunities. John Forester (1987) – ‘Planning in the Face of Conflict’ Moving on to the second article selected we are in a way turning from the future concerns of Wheeler to the present day framework in which planning (mainly concerning the public sector) tends to take place. For planners working in the public sector in a developed country, the settings Forester describes must appear very much close to home. ‘Planning in the Face of Conflict’ constitutes a qualitative study performed through various interviews with members of the planning profession to gain an insight into which considerations and strategies these planners adopt when dealing with various conflicts. The article first gives an overview of the challenges, contradictions and paradoxes planners are presented with even before they begin. They are constantly pulled back and forth between ‘multiple, ambiguous and conflicting political goals’ (Forester 1987, p. 423), legal mandates, the demands of residents as well as professional norms and their own personal visions. The picture that emerges here is one of a delicate balancing act. Other external factors are equally complicating. Planners have to make judgments with longlasting consequences but without having all the information. This creates a very high level of uncertainty. Then there is the question of imbalances of power between different actors with an interest in a certain development. The following table illustrates Forester’s point: 3 Developers - Residents respond to developments Have ‘lungs’ borrow expertise Have time, though rarely turned into real negotiating power don’t speak ‘development language’ don’t speak with one voice initiate developments invest capital and financing hire expertise have money speak ‘development language’ speak with one voice The main bulk of the article deals with how to negotiate and/or mediate between these very different parties including various strategies of achieving optimal outcomes for all concerned parties. One of Forester’s main concerns is the dual role of negotiator and mediator a planner has to fulfill. The negotiator seeks to achieve a particular outcome to satisfy a particular interest, while the mediator is ‘stuck in the middle’ resolving conflicts through facilitating participation. What becomes apparent is that planners are virtually surrounded by both internal and external conflicts during all of which their position needs to remain clear and predictable – not an easy task. Something that planners can employ to their advantage, according to Forester’s research, is a significant amount of discretion defined by ‘formal responsibilities’ and ‘informal initiatives’ (Forrester 1987, p. 423). The complexity of the issues involved is also something which creates leverage for planners, for instance, when a less knowledgable party is forced to rely on their expertise or when they are free to interpret legislation a certain way. Thinking strategically about time is another tool at the planner’s disposal. A developer may be more willing to comply if he is slowed down as every delay ends up increasing his costs. Similarly, waiting to push for changes can give a planner’s favoured projects more chance of success. Before finally moving on to Forester’s six strategies, I would like to mention briefly the different roles planners may choose to fulfill or are forced into. I already mentioned the at times conflicting roles of negotiator and mediator. Forester also identifies three further roles: rule enforcers, resource people and shuttle diplomats. Rule enforcers state clearly what the law allows and move the discussion away from unrealistic options. Resource people provide information and interpretations to help with the decision-making process. Shuttle diplomats, then, extract each side’s ideas and concerns individually to present them with comments to the opposite party. Forester lays out six different strategies or ways in which planners can choose to exert their discretion, many of them dealing with the emotional complexity of the task at hand. For instance, one ‘community-organiser-turned-planner’ (p. 431) points out that appearing rational and objective may sometimes be counterproductive as the person on the other side may be quite emotionally (and/or financially) invested in a project and needs to know that you, the planner, care as well. Keeping in mind that one may have to maintain a healthy longterm working relationship is crucial in deciding how and when to argue a point and when to 4 approach the issue a different way at a different point in time. As one planner put it, the planner’s task is 25% technical skills but 75% diplomacy (p. 432). Whether or not the exact percentages are true, one instinctively tends to agree with the general point, reevaluating the importance of ‘people skills’ over technical ones. Each of the planners interviewed by Forester employed one or several of the strategies described here to improve both the process of decision-making as well as the final outcome. The planner as regulator (1) provides information about the technical requirements and what is permissible under current legislation, but also makes professional judgements and gives recommendations. Power imbalances are not considered in such an approach, everybody is treated equally. The pre-mediator (2) relays what he or she thinks neigbourhood concerns are to developers before the fact to make them consider alternatives. This obviously raises questions of how the planner knows which concerns are most relevant and in what relationship he or she stands towards the residents. The planner as resource (3) encourages informal back and forth meetings between developers, neighbourhood representatives and elected members. His job is simply to explain the rules, not to act as a “neutral”. This seems to be the most passive out of all the approaches. As mentioned before, the shuttle diplomat (4) bounces ideas off each side individually allowing him to bring in his own ideas without the other side using them against him. Shuttle diplomats argue that one would lose one’s ability to be frank if both parties were present. The active and interested “non-neutral” (5) tries to build understanding between the two sides, let each side prepare their own defense against possible arguments while making sure that real evidence is not ignored. With such an approach anticipating issues early on is of vital importance. The final approach is the planner as professionally interested negotiator with the mediator role being delegated to a third party (6). One planner applying this strategy identified so strongly with the ‘political and professional mandate’ of his position that a neutral mediator role was out of the question (Forester 1987, p. 430). The final advice Forester gives to local authorities for implementing some or all of these strategies into their everyday work processes appears sound: conceding that processes still need to be flexible enough to allow for different circumstances as treating every project with the same formula would not be appropriate. Nevertheless, he argues that there is still scope and opportunity for applying these strategies regularly, especially if all parties are convinced that they lead to “both gain” outcomes. Tanja Winkler (2011) ‘Between Economic Efficacy and Social Justice: Exposing the Ethico-Politics of Planning’ Turning to the last piece selected, we are shifting our focus again from the present to the past, to where planning has come from, its ideological and theoretical roots and how these are still 5 influencing planning practice and discourses about planning today. Tanja Winkler, a planning researcher at the University of Cape Town, argues that the paradox in liberal democracies of having to both provide for economic growth and social justice is rooted in liberalism itself. She delineates the conflicted nature of liberalism as a philosophy and as a model for government. Finally, she argues that the role liberal thinking plays in shaping public policies needs to be questioned in order to discover alternative possibilities for planning. As some of Winkler’s points overlap in the course of her article, I will try to summarize and restructure them into what I understand to be a more clear and linear representation of her argument. To avoid cluttering the text with citation references, I will try to use them only where I believe them to be strictly necessary. Winkler starts out with two observations: (1) following the global financial crisis, the opposition to austerity measures imposed on developed countries (especially in the Eurozone) is putting pressure on policy makers to rethink and reconcile policies for economic competitiveness with those for social justice. (2) the idea of free-market policies as a catalyst for growth has been imported from the North to the South, even though the political, economic, social and urban contexts in the South are radically different. The example of the city of Johannesburg is cited. This has created a greater need for social justice policies in these countries. For Winkler the question arising from these two observations is not primarily of how to reconcile the paradox, but rather to name the origins of this paradox and then question the practical relevance of these origins today. Following Roy’s claim that ‘liberalism is planning’s most influential ancestor’ (Roy 2008, p. 97) she proposes that planning in liberal and socioliberal democracies is governed mainly by liberal norms and that these should be questioned in order to discover new approaches and possibilities (Winkler 2011, p. 167). For chronology’s sake, let us first turn towards the history of liberalism as described by Winkler since it is one of the premises of her argument. Liberalism originated out of the need to emancipate subjects from serfdom, proposing minimal state control while being based on the idea of the self-regulating market. Yet at the same time, it was also born out of the skepticism that free citizens would still not be reasonable enough to temper their selfinterests for the benefit of others and the common good. Thus, some form of government was deemed to be necessary. This meant that from the outset liberalism was a conflicted philosophy, ever caught between governing too little and governing too much. Adam Smith recognized this conflict in The Theory of Moral Sentiments when he admitted that ’”the private interests of men [sic]’’ are desirable only when these interests lead to ‘‘the interests of the whole society’’’ (Smith 2000 [1759] cited in Winkler 2011, p. 168). Another weight was added to the balance tray of control with the rise of statistics in the 19 th century which necessitated a form of government that statistically improved the material conditions for individuals and society by regulating and controlling private interests. The 6 increase in health, sanitation and housing by-laws during that time were an outcrop of that thinking. Finally, the utilitarian approach to liberalism, most notably represented by John Steward Mill, argued that restrictions on trade would interfere with the efficiency of the economy and individual liberty. He and others proposed that these measures were indeed not necessary if only people were ‘morally improved’ enough through education in such a way that this would instill them with habits of self-government. These habits would be based on the idea of moral obligations towards others for a collective good. Again following Roy’s interpretation, Winkler argues that this three-pronged set of ideas with the notion of serving the public interest at the centre, is in fact what has been forming the ‘ethico-politics’ of planning until today. To rephrase this in plainer terms, what she must mean is the ethical and moral framework which has since then guided planning decisions in liberal and socio-liberal democracies (Winkler 2011, p. 168). Planning as a profession then developed out of the fact that social problems in the 19th century started to be linked to spatial concerns. Space was seen to shape the individual and thus society as a whole. The need was felt to both represent the spatial reality, presumably in theoretical terms, but also to design reasoned spatial interventions for it. Thus, planning as a profession came into being. This coincided with the creation of the first ‘welfare states’ in which planners were seen as objective professionals who could make ‘moral judgements’ on how to improve the spatial reality in the name of public interest (Winkler 2011, p. 169). This last point warrants some further interpretation as the very technical craft of planning in the 19th century is, at least in my conception of it, rarely associated with having considered issues of ‘morality’. But what I presume Winkler means is that the impetus for improving living conditions for society as a whole stemmed from a moral obligation towards all parts of society which governments must have begun to feel at the time and that this task was, among others, then deferred to ‘experts’ such as the planning profession. This grounding in ‘moral obligation’ is what may be at the heart of planning’s claim to legitimacy and the legitimacy of intervention in general. At the same time, public interest was seen to also rest on “corresponding controls and selfcontrols by all individuals making up the population of a territory’’ (Huxley 2005 cited in Winkler 2011, p. 169). Again, Winkler is certainly able to find references to support her claim for liberalism’s influence on planning. Critique and the Johannesburg Case This reliance, one might almost say ‘trust’, in individuals to act rationally and ethically towards others if one were only to improve the spatial aspects of human life is what Winkler criticises about the liberal approach as being too optimistic. She also criticises that this approach has been imported to many countries in the global South, regardless of whether or not it is applicable in this significantly different context. Both criticisms go beyond the scope of this essay to assess, yet instinctively appear to have the ring of truth. Finally, it is argued that the inherent tension between planning for public interests and economic 7 competitiveness creates insecurities and instabilities which are certainly undeniable (Winkler 2011, p. 169). Winkler illustrates her critique of the implementation of the liberal approach to governance with an example of the city of Johannesburg. Spawned by the debilitating economic effect of some blighted areas of inner city Johannesburg, the local authority found the political will to initiate fiscal and physical interventions in these areas to foster economic growth. However, in pursuit of this, 125 illegal occupiers of ‘bad buildings’ were evicted between 2002 and 2006 without providing suitable accommodation in return. When citizens – as free individuals - appealed against this eviction to the highest court in South Africa, the eviction was deemed unlawful and the municipality was ordered to provide evictees with accommodation, stating that both parties should act ‘reasonably and in good faith’ (Winkler 2011, p. 171) for each to understand its obligations towards oneself and to others. The state was seen to have ignored its moral obligation to safeguard both public and private interests. Again, this is the notion of ‘public morality’ mentioned earlier. Yet what happened in response to this verdict was evictees being moved to a state-managed facility without negotiation which significantly deprived them of their freedom to self-control. Here, we see a discrepancy between regarding citizens as ‘free’, for instance to judicially challenge how they are governed, and how imbalances of power are eventually able to warp these notions into justifying the infringement of the individual rights of these citizens. What Winkler is pointing to here is the large gap between liberalism as a concept for government and the reality of how it is actually applied. While Johannesburg expressly stated its ‘commitment to the poor’, this commitment was, again, often undermined by the presupposition that the ‘lower’ sections of society would disregard public interests, for instance, in terms of maintaining buildings or preventing litter (‘failure to self-control’), and that this could only be prevented through a programme of education (‘control’ and ‘moral improvement’) of those sections of society. As policymakers see a ‘demonstrable relationship’ between ‘grime and crime’ these education measures would then also facilitate the stricter enforcement of by-laws which in turn would lead to a decrease in crime. Apart from possibly constituting a case of confusing correlation and causation on the part of policymakers, Winkler also sees a distinct double-standard in that middle-class citizens are clearly not considered to be in need of similar ‘moral improvement’ measures. This represents another loss for social equity as liberal norms are applied differently to different sections of society. Winkler’s final point then is that planning and policymaking are ‘instruments of control and public morality’ rather than drivers for change and that this framework “remains unaltered regardless of residents’ legal actions and constitutional rights”. While not stating that this framework is “inappropriate or unjust” she proposes to challenge the “entrenched ‘norms’ of planning that stem from its foundations in liberalism” (Winkler 2011, p. 172). Her point is clearly well-made, though it remains unclear what, in her mind, planning as a ‘champion for change’ would entail. However, this may be exactly the kind of question Winkler intends us to ask ourselves after having followed her argument. 8 Comparison Comparing such diverse texts as these is easy when pointing to their differences. Wheeler’s text is descriptive, ‘big picture’ and forward-looking; Forester’s is personal, practical and present-focused; Winkler’s is academic and theoretical yet her underlying concern for a realworld paradigm shift in planning is palpable. How do they differ in terms of the clarity of their message? Wheeler, in my opinion, succeeds in setting the stage for this daunting human task and a more in-depth look at all the individual challenges mentioned, and I believe it could become a core introductory text for planning students in the coming years. The importance of Forester’s text is unquestionable as it was one of the first texts to bridge the gap between theorists and practitioners. It clearly spells out the fact that planners will have to face and work with conflicts in their professional lives but also offers advice on how to do this. In this respect, ‘Planning in the Face of Conflict’ is an immensely valuable resource. What I would like to point out, though, is its possible lack of relevance in other parts of the world. Forester’s research is largely based on his experience as a planner in the United States – but how would these strategies apply in, say, dictatorial regimes like China or African countries where civil society is much less developed or even non-existent? What kind of strategies would planners apply in these countries to ‘face down’ power or mediate? And mediate between whom? Considering the immensity of urban challenges in the global South, this constitutes a void which other planning theory texts will have to fill (Vanessa Watson’s (2012) ‘Planning and the ‘stubborn realities’ of global south-east cities: Some emerging ideas’ comes to mind). Winkler’s text represents perhaps the boldest of the three as it tries to question the very foundations on which planning rests. The difference between her approach and either Wheeler’s or Forester’s may be compared to the difference between ‘Big Coefficient Thinking’ and ‘New Reality Thinking’. Big Coefficient Thinking is about finding the coefficient with the biggest magnitude, that is, the biggest influence on either policy or practice and trying to contribute towards that. Wheeler chose awareness of the ‘big picture challenge’, Forester chose the understanding of conflicts and how to solve them. Both of their causes are relevant and important, yet what Winkler is trying to do is finding a completely new way of looking at the norms and values that underlie planning and what it understands its role in society to be. Does it want to be an instrument of control and public morality or does it want to be a ‘champion for change’? Even though the density and complexity of her language may obscure her message to some degree, I believe her text to be the most powerful and relevant of the three texts chosen for this essay. 9 [4452 words excluding cover page and references] References Forester, J. (1987) ‘Planning in the Face of Conflict’ in The City Reader: Fifth Edition. ed. by LeGates, R. and Stout, F. New York: Routledge, 421-434. Huxley, M. (2005) The soul’s geographer: Spatial rationalities of liberal government and the emergence of town planning in the twentieth century. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Milton Keynes: The Open University. Roy, A. (2008) ‘Post-liberalism: On the ethico-politics of planning’. Planning Theory 7(1), 92–102. Smith, A. (2000) The theory of moral sentiments. London: Prometheus Books. Van der Werf, G.R. et. al. (2010) ‘Global fire emissions and the contribution of deforestation, savanna, forest, agricultural, and peat fires (1997–2009)’. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Discussions (10), 16153–16230. Wheeler, S. (2011) ‘Urban Planning and Global Climate Change’. in The City Reader: Fifth Edition. ed. by LeGates, R. and Stout, F. New York: Routledge, 458-468. Winkler, T. (2011) ‘Between Economic Efficacy and Social Justice: Exposing the EthicoPolitics of Planning’. Cities 29, 166–173. Watson, V. (2012) ‘Planning and the ‘stubborn realities’ of global south-east cities: Some emerging ideas’. Planning Theory 0(0), 1-20. 10