Practitioners - Knowsley Safeguarding Children Board

Knowsley Early Help System

Integrated Working

Effective Early Help

Assessments

Practitioners

Handbook

January 2015

This Practitioners Handbook has been developed with the support and contributions from staff and volunteers who work with children, young people and their families in

Knowsley.

It has been endorsed by Knowsley Safeguarding Children Board who will hold to account all agencies in respect of delivering high quality, effective early help assessment and interventions that meet the needs of children and young people and keep them safe.

First Edition Published January 2015

Page | 2

1 Key principles of effective early help in Knowsley

Based on what we know from recent publications, professional expertise and local knowledge, below are outlined the key principles of effective early help in Knowsley together with our measures of success that will evidence the benefits to families.

Key principles

There are effective systems, tools and processes in place to support early help

A comprehensive and well co-ordinated offer of good quality early help services

Everyone has a part to play in a system of early help

Targeting those most at risk and those where early help is likely to have most impact

Indicators of effective early help

Measures of success which will evidence the benefits to families include:

More young people leave school with a good level of educational attainment

More young people regularly attending school

Fewer exclusions from school

Narrowing the gap between children achieving well on the early years foundation stage and those doing less well and more children accessing free high quality early education and childcare provision

Fewer repeat referrals needed into social care

Fewer children and young people report they feel at risk

Reduced number of repeat child protection interventions to prevent further harm

Children achieve permanence more quickly if they are unable to live with their families

Fewer first-time entrants into the criminal justice system

More young people are in education, training or employment

More young people make positive choices in relation to risk taking behaviour

More children with special educational needs and disabilities supported in universal settings

More young people report increased resilience and self-esteem

Page | 3

2 The voice of the child

The vision of children implicit in the UNCRC and in the Children Act 1989 is that children are neither the property of their parents nor helpless objects of charity. They are individuals, members of a family and a community, with rights and responsibilities appropriate to their stage of development.

Professor Eileen Munro introduced the term ‘The Child’s Journey’, meaning the child’s journey from needing to receiving effective help for problems arising from family and social circumstances. It was further noted that while many professionals make strenuous efforts to keep a focus on the child, there are aspects of the current system that push practitioners into prioritising other aspects of their work.

“The child protection system should be child-centred, recognising children and young people as individuals with rights, including their right to participate in major decisions about them in line with their age and maturity.

Although a focus of work is often on helping parents with their problems, it is important to keep assessing whether this is leading to sufficient improvements in the capacity of the parents to respond to each of their children’s needs.”

The Munro Review of Child Protection Final Report, 2011

Failings in safeguarding systems are too often the result of losing sight of the needs and views of the children within them, or placing the interests of adults needs ahead of the needs of children. As noted in Working Together to Safeguarding Children

2013, children are very clear what they want from an effective safeguarding system.

Anyone working with children and young people should see and speak with them; listen to what they have to say about their life and circumstances; take their views seriously; and work with them collaboratively when deciding how to support their needs. This is a child-centred approach.

Children and young people are a key source of information about their lives and the impact any problems are having on them in the specific culture and values of their family.

Participation can be empowering for a child or young person if undertaken well.

Some of the core skills required for effective communication with children and young people include listening, being able to convey genuine interest, empathic concern, understanding, emotional warmth, respect for the child, and the capacity to reflect and to manage emotions (Jones D.P.H., 2003).

Page | 4

Children have said that they need

Vigilance : to have adults notice when things are troubling them

Understanding and action : to understand what is happening; to be heard and understood; and to have that understanding acted upon

Stability : to be able to develop an on-going stable relationship of trust with those helping them

Respect : to be treated with the expectation that they are competent rather than not

Information and engagement : to be informed about and involved in procedures, decisions, concerns and plans

Explanation : to be informed of the outcome of assessments and decision and reasons when their views have not met with a positive response

Support : to be provided with support in their own right as well as a member of their family

Advocacy : to be provided with advocacy to assist them in putting forward their views

Working Together to Safeguard Children, Pg 10, 2013

Page | 5

3 Early Help Assessments

Across the children and families Partnership the EHA is the means by which we will identify additional needs of children, young people and their families. The assessment will:

help develop a shared u nderstanding of a child’s needs

help avoid children, young people and families having to re-tell their story

ensure we are assessing families’ needs properly and

help generate a whole picture of the services children, young people and families need and are being offered.

An EHA should always be considered and used when unmet needs have been identified (and consent received from the child/young person and/or their parent/carer, unless the case is so serious that consent can be waived) before any referral.

A holistic assessment process

An early help assessment is a holistic assessment of a child’s needs for services. It is a process for recognising signs that a child may have unmet needs that universal services cannot meet. It is also a process for identifying and involving other agencies who may be able to support the child and/or undertake a specialist assessment.

Central to the development of the assessment is the principle that it is child or person centred, holistic and can be shared with professionals as appropriate.

The assessment should be grounded in knowledge, i.e. theory, research findings and practice experience in which confidence can be placed to assist in the gathering of information, its analysis and the choice of intervention in formulating a plan.

When to use an EHA?

The EHA should be used at universal to complex, primarily as a holistic assessment of need to support multi-agency work. It should be used whenever there is a concern about a child or young person’s well-being and the cause and appropriate response are not clear.

Some of the reasons why you might use an EHA are noted below:

You are concerned about how the child/young person is progressing, in terms of their health, welfare, behaviour, learning, or any other aspect of their wellbeing

You receive a request from the child/young person or parent/carer for more support

You are concerned about the child/young person’s appearance or behaviour, but their needs are unclear or are broader than your service alone can address

Page | 6

There is persistent absenteeism from school

There is a teenager under 16 years who is pregnant or they are teenage parents

The young person is homeless and not receiving support from a social worker

The young person requires a referral to substance misuse services

Children/young people require additional support to prevent their entry into the youth justice system

Practitioners should, in particular, be alert to the potential need for early help for a child who:

Is disabled and has specific additional needs

Has special educational needs

Is a young carer

Is showing signs of engaging in anti-social or criminal behaviour

Is in a family circumstance presenting challenges for the child, such

as substance abuse, adult mental health, domestic abuse; and /or

Is showing early signs of abuse and/or neglect

WTSC, 2013

The holistic picture gathered through the EHA process might then underpin either a single-agency response of a joint-agency response, a coordinated multi-agency response organised by a Lead Professional and a TAF.

When approaching children, young people and families about issues it is important to be open and relaxed with your questioning style. You should advise them that the process is about supporting them to make changes in their lives and that the more information you gain the more tailored the support can be to best suit their needs.

Page | 7

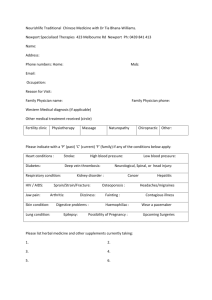

Worried/concerned/unmet needs about a child? Discuss with your line manager. Consider what you need to do to help. You have a responsibility to take appropriate action.

Child at risk of immediate/significant harm or acute need identified? If yes, contact KAT

No

Practitioner to ascertain if EHA has already been completed and / or if any other service is involved with the child / young person / family.

Yes

KAT decision.

Has the threshold been met for Social

Worker assessment.

Yes

Social

Worker

Assessment

Is an EHA required?

Yes No

Complete EHA, consider Single Agency support required

Yes

Delivery

Is a multi-agency response required?

No

Yes No

Agree action plan and set time and date for

TAC/TAF

Yes

Continue with Single

Agency Delivery

Review: Have all needs been met?

Yes

Step Down to universal services

Review action plan.

Reconsider unmet need and seek appropriate consultation and additional support from targeted support services.

No

Provision of advice and guidance

Request other service to assist by offering early help using EHA to support unmet needs.

Refer to other agency.

T

No

Review: Worry/Concern/Unmet needs?

Yes

Continue with support until step down to universal services

Step Up

Child at risk of immediate / significant harm or acute need identified? Contact

Knowsley Access Team.

Page | 8

When not to do an EHA ?

If you think the child is a ‘Child in Need’ which includes being at risk of significant harm, you should follow the established child protection procedures immediately.

There is no need to do an assessment for every child you work with. Children who are progressing well or have needs that are already being met do not need one.

You don’t need to do an assessment where you have identified the needs of the child and your service alone can meet them. When the child/young person:

Already has an active referral open with children’s social care

Is a looked after child or has a child protection plan

Or their parent/carer does not give consent; the assessment is voluntary

Person Centred Planning

Person centred planning is a process of continual listening, and learning; focussed on what is important to someone now, and for the future; and acting upon this in alliance with their family and friends. It is not simply a collection of new techniques for planning to replace Individual Programme Planning. It is based on a completely different way of seeing and working with people, in particular those with disabilities, which is fundamentally about sharing power and community inclusion.

Person centred planning requires that practitioners have a flexible and responsive approach to meet peoples’ changing circumstances, guided by the principles of good planning rather than a standard procedure. Practitioners need to be constantly problem solving in partnership with the child/young person and their family.

Five key features of person centred planning:

1. The person is at the centre

The person is consulted throughout the planning process

The person chooses who to involve in the process

The person chooses the setting and timing of meetings

2. Family members and friends are partners in planning

3. The plan reflects what is important to the person, their capacities and what support they require

Focused on capacities

Identifying supports

A shared understanding – rethinking the role of professionals

Discovering what is important to the person

4. The plan results in actions that are bout life, not just services and reflect what is possible, not just what is available

5. The plan is ongoing, listening, learning and further action

Page | 9

Structuring your discussion with children, young people and families

You talk to the child/young person and their parent/carer and wider family members where appropriate; discuss the issues with them and what you can do to help. You then speak with anyone else you need to for example your manager, colleagues and other staff (including those in other agencies) that are already involved with the child/young person and/or parent/carer. You check if a CAF already exists for the child/young person. Reflecting on the information you have gathered you decide that an early help assessment would be useful and seek the agreement of the child/young person and their parent/carer as appropriate.

You talk with the child/young person, parent/carer or wider family members and complete the assessment with them. The Early Help Mind Maps have been designed for the child/young person, parent/carer to complete in their own words to help practitioners to see things from their perspective. You should use information you have already gathered from the child/young and family members or other practitioners so that they do not have to repeat themselves. If you have identified that an assessment already exists you add to or update it with the family. At the end of the discussion you should have a better understanding of the child/young person and family’s strengths, needs and what can be done to help. You agree actions that your service can deliver and the family can deliver. You also agree with the child/young person and the family any actions that require others to support. You record this on the assessment form.

You deliver your actions within the agreed timeframe. You make requests for support or broker access to other services for support, using the assessment to demonstrate evidence of need. You monitor progress against the plan.

Where the child/young person or family need support from a range of services, there should be a Team Around the Family (TAF) meeting. This will be arranged with the help of the Early Help Coordinators to ensure all required services are fully engaged and involved in planning actions and monitoring progress.

Thinking, judging and analysing are essential to formulating effective plans for children and young people. The following five questions will help structure the conversation: 1. What is the assessment for? 2. What is the story? 3. What does the story mean? 4. What needs to happen? 5. How will we know we are making progress?

Page | 10

Information sharing and consent

– a partnership with the child/young person and parent/carer

The assessment process is designed to be empowering for children, young people and families. You should discuss your concerns with the child/young person and their parent/carer before deciding whether to complete an Early Help Assessment or not.

Consent is the key to successful information sharing and central to the assessment process as without it the assessment process cannot proceed. As such, it is essential that children, young people and their family understand the process and how their information will be shared between agencies.

Throughout the process, practitioners should discuss the issue of consent with the family and explain why it may be necessary for agencies to share information. The practitioner should be clear about what information is likely to be collected, how it will be used, who it will be shared with and why. Children, young people and their families may agree only to partial consent, specifying what information may be shared and with whom. The individual’s wishes should be respected, unless a child is at risk of harm.

There are some circumstances in which it would be appropriate to share information without consent, such as:

the disclosure prevents the child/young person from committing a criminal offence or places the Practitioner at risk of collusion;

the child/young person is at risk of significant harm or harming someone else;

the information is required as part of a legal proceeding;

information is requested by the police as part of a criminal investigation;

in any other circumstance where public interest overrides the need to keep information confidential.

When decisions are made to share information without consent, the reasons for doing so should be recorded and the family should be made aware (if this does not place the child at increased risk of harm).

Working with young people and consent

Although the assessment process focuses on the need to share information and the importance of including the whole family in assessment, Knowsley recognises that young people may not always want to involve their families in decision making. As such, procedures have been established to allow young people to consent to the assessment process.

When working with a young person it is important to encourage them to discuss issues with their parents/carers, however this may not always be appropriate. At this point, depending on the young person’s needs, it should be explained that only limited support may be offered to meet their needs as many services work with the whole family. However, the young person should be reassured that the appropriate services will work with him/her and respect their wishes if they are deemed to be

Page | 11

‘Gillick Competent’ or whether they meet the ‘Fraser Guidelines’.

What is Gillick Competency? What are the Fraser guidelines?

(Written and compiled by the NSPCC Safeguarding Information Service, December

2009)

When deciding whether a child is mature enough to make decisions, people often talk about whether a child is 'Gillick competent' or whether they meet the 'Fraser guidelines'.

What do 'Gillick competency' and 'Fraser guidelines' refer to?

Gillick competency and Fraser guidelines refer to a legal case which looked specifically at whether doctors should be able to give contraceptive advice or treatment to under 16-yearolds without parental consent. But since then, they have been more widely used to help assess whether a child has the maturity to make their own decisions and to understand the implications of those decisions.

In 1982 Mrs Victoria Gillick took her local health authority (West Norfolk and Wisbech

Area Health Authority) and the Department of Health and Social Security to court in an attempt to stop doctors from giving contraceptive advice or treatment to under 16year-olds without parental consent.

The case went to the High Court where Mr Justice Woolf dismissed Mrs Gillick’s claims. The Court of Appeal reversed this decision, but in 1985 it went to the House of Lords and the Law Lords (Lord Scarman, Lord Fraser and Lord Bridge) ruled in favour of the original judgement delivered by Mr Justice Woolf:

"...

whether or not a child is capable of giving the necessary consent will depend on the child’s maturity and understanding and the nature of the consent required. The child must be capable of making a reasonable assessment of the advantages and disadvantages of the treatment proposed, so the consent, if given, can be properly and fairly described as true consent."

Below is some further guidance to help you determine and record your decision as to whether a young person is able to participate in the early help assessment process without the involvement and support from their parent(s) / carer(s).

Has the young person explicitly requested that you do not tell their parent(s)/carer(s) about the early help assessment and any services that they are receiving?

Have you done everything you can to persuade the young person to involve their parent(s)/Carer(s)?

Have you documented clearly why the young person does not want to inform their parent(s)/Carer(s)?

Can the young person understand the advice/information they have been given and have sufficient maturity to understand what is involved and what the implications are?

Can the young person comprehend and retain information relating to the early help assessment and the services, especially the consequences of having or

Page | 12

not having the assessment and services in questions?

Can they communicate their decision and reasons for it?

Is this a rational decision based on their own religious belief or value system?

Is the young person making the decision based on a perception of reality e.g. this would not be the case for a chaotic substance misuse?

Are you confident that the young person is making the decision for themselves and not being coerced or influenced by another person?

Are you confident that you are safeguarding and promoting the welfare of the young person?

Without the service(s), would the young person’s physical or emotional health be likely to suffer? (if applicable)

Wou ld the young persons’ best interests require that the early help assessment is done and the identified services and support provided without parental consent?

You should be able to answer YES to these questions to enable you to determine that you believe the young person competent to make their own decisions about consenting to taking part in the early help assessment, sharing information and receiving services without their parent(s)/carer(s) consent. You should record the details of your decision making.

Cultural sensitivity

Cultural variations in child-rearing patterns do exist and a balanced assessment must incorporate a cultural perspective. When planning the assessment practitioners need to establish each family’s particular needs with regard to their culture, race, religion etc. Some questions which may need to be considered include:

Is it possible to allocate a worker from the same cultural background as the family?

Is it possible to co-work with an individual who can assist the practitioner in understanding the cultural issues?

Is an interpreter required?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of doing this?

Most importantly a practitioner that is working with a child, young person and their family of a different racial origin from themselves should ensure they are as familiar with the family’s culture as possible, through reading research and asking questions.

Practitioners should always be prepared to explain to children and families which particular questions need to be asked, particularly when they can be seen as intrusive. By doing so, families are more able to make an informed choice about responding or not.

Page | 13

Team Around the Family (TAF)

The aim of the ‘Team Around the Family’ is to provide a more integrated approach to support within existing resources, reduce duplication and support a common service delivery approach which continues from the early help assessment process. A TAF aims to p lan actions around the child/young person’s identified unmet needs through an agreed written TAF plan.

Practitioners may be involved in the TAF in a number of different ways, for example:

As the Lead Practitioner having completed an early help assessment

As a practitioner involved with the child or family

For information, consultation and advice

Delivery of support services

Parents/carers should have an active role in the TAF and their contribution should be recognised as they have a central role in meeting the needs of the child/young person. Some parents/carers may themselves need to be supported to achieve this due to their own unmet needs.

Practitioners in the TAF should consider solutions that include building on the family strengths and univers al children’s services, as well as statutory services. It is important that the team are creative in finding needs-led solutions.

The functions of the TAF include:

Reviewing and agreeing information shared through the assessment

Planning and agreeing actions with timescales

Identifying solutions, allocating tasks and appropriate resources

Agreeing the Lead Professional

Monitoring and reviewing outcomes with timescales

Reporting, as required, to other review meetings or resource panels

Identifying gaps and informing planning and commissioning

The membership of the TAF will inevitably change as the needs of the child/young person and family change. The TAF operates as a supportive team, rather than just a group of practitioners and family members. In this way there is direct benefit to parents who have new opportunities to discuss their child and family with key practitioners all in one place and to practitioners who might otherwise feel isolated and unsupported in their work with the child, young person and family.

The TAF always has a Lead Practitioner and an agreed plan of involvement. It is paramount that the child/young person and parent/carer can relate to the practitioners involved.

Good practice suggests that the initial TAF meeting should happen within 4 weeks and then be reviewed no more than 3 months. Meetings should be arranged according to the identified needs. At least two weeks prior to the review meeting the family should be asked to review the RAG ratings they indicated in the initial assessment and update these as they see appropriate. At the review meeting the

Lead Practitioner will revisit the original assessment and RAG ratings and with the family reflect on the revised ratings and the outcomes identified in the plan.

The Role of the Lead Practitioner

The Lead Practitioner (LP) will be the practitioner with the most relevant skills and experience that the child/young person, parent/carer know and possibly already have a relationship with. Their role is to ensure that services are coordinated, actions completed, share information and monitor progress.

The Lead Practitioner is not a new role. Instead, s/he deliver three core functions as part of their work:

act as a single point of contact for the child or family;

co-ordinate the delivery of the actions agreed;

reduce overlap and inconsistency in the services received

A Lead Practitioner is accountable to their home agency for their delivery of the lead professional functions. They are not responsible or accountable for the actions of others.

This role can be taken on by different types of practitioners in the wider children’s workforce. This is because the skills and knowledge required to carry out the role are similar, regardless of professional background or job.

The Lead Practitioner needs the knowledge, competence and confidence to develop a successful and productive relationship with the child and family, and communicate without jargon.

Responsibility for meeting the unmet needs of the child/young person lies with the whole team, with the Lead Practitioner having a coordinating role.

Where the child/young person or parent/carer does not consent to information being shared or to the TAF process this is factored into the assessment so that the most relevant way forward for all concerned can be taken.

The Lead Practitioner role should help to increase choice for children, young people and their family and improve the effectiveness and efficiency in the delivery of support services.

Young people should also have a say in who will act as their Lead Practitioner.

Provided they have the skills and knowledge, any Practitioner may be requested to act as a Lead Practitioner, meaning that those who specifically work with young people, such as a Youth Worker or a Connexions Personal Adviser, could take on this role. The young person should feel comfortable with the Practitioner and able to express their opinions, knowing that the Practitioner will work in partnership with them to ensure their needs are met.

Becoming a Lead Practitioner does not imply that the person does all the work and is singly accountable. It is important that all practitioners involved in the

TAF recognise that they continue to be accountable for the child’s welfare.

Page | 15

The Role of Early Help Coordinator

The Early Help Coordinators are part of a team whose role it is to coordinate, develop and sustain the Early Help Assessments and interventions to ensure the

Early Help Assessment Framework is embedded in good practice throughout the children’s workforce in Knowsley.

The Early Help Coordinators will work with parents, carers, practitioners and voluntary groups to support the implementation of integrated processes (Early Help

Assessment Framework), Lead Practitioner and TAC and TAF meetings to secure the wellbeing of children and young people.

The Early Help Coordinators will:

coordinate and chair TAC/F meetings so they take place with the right people at the right time with the right information

organise arrangements for TAC/F meetings including the collation & distribution of appropriate documentation to all relevant parties

advise on who would be the most appropriate Lead Practitioner to coordinate multi-agency plans

advise and support the Lead Practitioner to carry out their roles in liaison with their line managers

work with the Early Help Champions in agencies to enable them to provide advice, guidance and support colleagues working with vulnerable children and young people throughout the borough

maintain effective monitoring and evaluation processes of the Early Help

Assessment Framework and produce statistical information relating to trends and predicators of need

facilitate the active community involvement and participation in the Early Help

Assessment Framework and associated processes

work with the Early Help Assessment Manager and Early Help Champions in developing, delivering and sustaining multi-agency training to relevant practitioners

Page | 16

Dealing with persistent non-engagement with services by uncooperative families

There are frequent occurrences where children, and/ or their families, have a request for service(s) referred to an agency without their full appreciation of the need for a service or indeed with open objections to that request.

Professional judgment, based on evidence gathered via an assessment, shows that the plan needs to be actioned in the interests of the child. As such, there is a need for all agencies involved in providing support and safeguarding children to be alert to the different types of non-engagement and react to it in a consistent and effective manner. Persistent non-engagement with a service should trigger a review and impact assessment in respect of any children within a family.

Where a request for support is accepted by an agency as valid, necessary to ensure the child is kept safe and able to thrive, and where the request is based on assessed need, it should be considered that the engagement of the parents is required. By refusing to work with the agency in completing the assessment, the parents or carers would be potentially causing neglect to the child: "avoidable impairment" of health, education or other need.

What is persistent?

A useful definition is "unrelenting, steadfast opposition to a course of action proposed".

Issues to be considered when determining the action required are;

Impact on assessment - if there are outstanding areas of assessment to be completed, can this be done via liaison with other professional colleagues who would be able to share the information with other agencies

Impact on the child/family - if the recommendations are not carried out, will the child suffer Significant Harm and what will be the effect be on the family functioning? For example, will stress levels increase to a level where breakdown is likely?

Impact on availability of resources - is this a one-off chance to access a resource for the child or their family?

Disguised Compliance

'Disguised compliance' involves a parent or carer giving the appearance of cooperating with agencies to avoid raising suspicions, to allay professional concerns and ultimately to diffuse professional intervention.

All agencies should collate details of failed appointments if they suspect a family is operating in this mode - this assists in evidencing this issue by giving an overview of co-operation levels and reason for failed appointments.

Managing persistent non engagement

Single agency approach - Within supervision, the practitioner and their line manager should discuss the case. Issues to be considered would include other

Page | 17

agency involvement, the use of EHA as a tool to inform decision-making, consultation with an Early Help Coordinator.

Multi-agency concern - If the single agency approach is not successful, a multiagency meeting under the EHA procedures is appropriate to explore whether there are other ways of engaging the family, for example, where it is believed that one agency has a more constructive working relationship with the family - this may be the school, health visitor or midwife who may be viewed as more acceptable than other services e.g. Children’s Social Care.

In all cases where a TAF meeting is convened but the family fails to arrive, professionals present should continue to meet and plan their engagement with the family. The purpose of proceeding will enable practitioners to explore, share and affirm the information held on single agency assessments as a means of updating

EHA and formulate and set a timescale for an engagement plan with the family concerned. This will vary according to each circumstance but must be reviewed within a maximum of 6 weeks.

Where Children's Social Care is not already involved and non-engagement continues, a worker from Children's Social care should be invited to attend the first multi-agency review, which should take place within 6 weeks. Children's Social Care workers should provide information and advice to the review about any strategies not yet known or tried and on the referral process to Children's Social Care where deemed appropriate. Children's Social Care should continue to attend reviews of the plan where appropriate.

Where Children's Social Care become involved and non-engagement continues, the multi-agency review will need to consider making a referral to Children's Social Care with a view to a Strategy meeting, Section 47 Enquiry and a Child Protection

Conference. It may, in some circumstances, be valid for the multi-agency meeting to decide to take no further action. This course of action should be confirmed and approved by line managers in each agency and only in the absence of safeguarding concerns.

No Access Visits

Each agency should have guidance in place for when a practitioner is unable to gain access to a home. Following a 'no access' visit the responsibility for any assessment of the situation rests with the practitioner who has been unable to gain access. The assessment should include:

Liaison with other relevant agencies;

The needs of the child and the parents'/carers' capacity to meet those needs;

The environmental context of the child's situation and;

Consideration whether immediate intervention is required to secure the child's welfare.

Where there are clear safeguarding concerns a referral should be made to Children's

Social Care. If there are clear indicators that a child is home alone and/or at risk of significant harm the Police should be called and the need for the child's immediate protection through Police Protection or an application for an Emergency Protection

Order should be considered.

Page | 18

Practitioner Tools and Resources

Ten things to consider when involving children in assessment

1. How well do you know the child and to what extent do you know their views, feelings and wishes? This includes describing your relationship with them, how you think they perceive you, how often you have seen them and in what context, i.e. where and who else was present.

2. Which adults (including professionals) know the child best (what is their relationship like and how well placed are they to represent the child’s views) and what do they think the child’s key concerns and views are?

3. What opportunities does the child have to express their views to trusted or

‘safe’ adults? Do they know how to access the right people, what would be the barriers and what has been done to ensure they know where to go if they want to talk to someone?

4. How has the child defined (if at all) the problems in their family or life and the effects the problems are having on them? This includes the child’s perceptions and fears; and what they themselves perceive as the primary causes of pain, distress and fear.

5. What opportunities has the child had to explore this?

6. When the child has shared information, views or feelings, in what circumstances has this occurred and what, if anything, did they want to happen? This should only be stated if known, i.e. can be clearly demonstrated.

Assumptions should not be made about a child’s motivations for communicating something.

7.

What has been observed regarding the child’s way of relating and responding to key adults, such as parents and foster carers? Does this raise concerns about attachment? This would include describing any differences in the way the child presents with different people or in different contexts and where conclusions are being drawn about the child’s attachment. The reasons for such conclusions should be clearly demonstrated.

8. What is your understanding of the research evidence in relation to how this child might have been affected by the experiences they have had? That is, what is the likely or possible impact on children who experience ‘X’, where X is the specific issue at hand, for example, parental alcohol misuse or domestic violence. This includes a consideration of potential harm along with resilience factors. How far is what you know of this particular child consistent with the above?

9. What communication methods have been employed in seeking the views and feelings of the child and to what extent have these optimised the child’s opportunity to contribute their views? Would the use of equipment, facilitators, interpreters, signs, symbols, play, story boo ks be helpful and are the child’s preferences are known?

Page | 19

10. How confident are you that you have been able to establish the child/young person’s views, wishes and feelings as far as is reasonable and possible? This would include consideration of things that may have hindered such communication such as pressure from other adults, time limitations, language barriers or lack of trust in the child/social worker relationship. How much sense are you able to make of the information you do have?

Page | 20

Building a toolkit for communicating with children

Here are some suggested items you might want to think about having in your resource bag:

Pens, pencils, felt-tips, colouring pencils, crayons, chalk.

Coloured paper, sticky paper, coloured sticky notes, bigger sheets of paper, small coloured notebooks.

Glue, scissors (not too sharp), cellotape.

Play dough and other similar material that you can make shapes out of.

Photographs

– cut outs from magazines, pictures of houses, animals, young and old people, children and photos of professions, for example, nurse, policeman, footballer. All photographs to be stuck on cards to make a set of flashcards – or you may be able to buy a set of flashcards.

Stickers showing feelings, including happy, sad and smiley faces.

Worksheets that focus on different subjects and feelings.

Hand puppets, dolls or other figures such as trolls and little animals.

Storybooks – either specialist books designed for working with children or just anything you can pick up from a children’s department in any good bookshop

– there are so many good children’s books available, covering a huge variety of subjects.

A selection of simple toys, for example, dinky cars, toy telephones, a magic wand (always helpful for making wishes), picnic sets.

A make-up bag and cosmetics for older girls

A selection of up-to-date teen magazines, which can be cut up and used to make pictures.

Page | 21

The Three Houses

The Three Houses tool for interviewing children was first created by Nicki Weld and colleagues in New Zealand and further refined and developed through the efforts of many international practitioners. This tool focuses on interviewing children through their own words and drawings focused on a ‘house of worries’, ‘house of good things’ and ‘house of dreams’.

Example

A child protection worker had to investigate a domestic violence case involving a mother, her boyfriend and children ‘Ramon’ (10 years) and ‘Stephanie’ (7 years).

The children had been interviewed twice previously but were very withdrawn, giving very little information. Knowing she needed to do something different, the worker conducted the third interview using the three houses tool.

After the children drew house outlines on three separate blank sheets, she gave the children the choice of which house they would start with. They began by together drawing cold and drafty stables where the boyfriend would often lock them at night together with his aggressive black dog. As the children drew, the worker would write their exact explanations alongside the drawings.

Next the children drew the following in the house of worries:

Ramon kicking and yelling at the boyfriend – this had never actually happened but it was obvious to the worker that it was important to let

Ramon draw this picture;

on the roof Stephanie drew her mother crying in distress;

Page | 22

in the roof space Ramon drew his bedroom which he said he hated including a broken window that made the room cold. Stephanie described that she didn’t have a bedroom since the boyfriend moved in but had her bed in a corridor;

a picture of the boyfriend yelling at the children for not finishing a meal; and

a fork, which he used to stab them if they did not eat their meals.

(Ramon showed the worker healing scars on his hand consistent with the tines of a fork.)

The children then went on to create their house of good things drawing their experience of visiting their father, and then on separate sheets of paper drew separate houses of dreams. Though Stephanie’s house of dreams was more colourful both showed them living with their mother, the boyfriend gone, each house protected by strong doors and guard dogs and them having good food, nice clothes and activities and their own rooms.

With the children’s permission, the worker showed the mother the children’s drawings, which led the mother for the first time to admit the problems at home.

The mother made commitments to leave the boyfriend but unfortunately was not able to and the children were brought into care. Nine months later when the mother was able to separate she came immediately back to the worker to work to get her children back.

This is an extract from The Munro Review of Child Protection: Final Report A child-centred system

2011, page 30-31

Page | 23