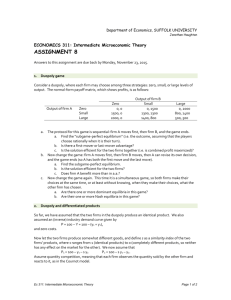

time - Economic Sociology Seminar

advertisement