Interaction in Online Learning: A Comparative Study on the Impact of

advertisement

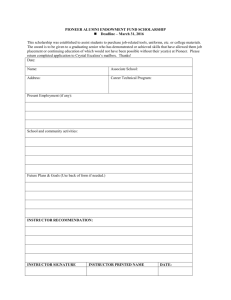

1 Interaction in Online Learning: A Comparative Study on the Impact of Communication Tools on Student Learning, Motivation, Self-regulation, and Satisfaction Moallem, M., Pastore, R. & Martin, M. Abstract The emergence of the newer web synchronous conferencing has provided the opportunity for high level of students to students and students instructor interaction in web-based learning environments. However, it is not clear whether absence or presence of synchronous or live interaction will affect the learning processes and outcomes to the same extent for all learners with various characteristics, or whether other factors that compensate for the absence of the live interaction can be identified and accounted for deeper learning processes and for higher quality of learning outcomes. The purpose of this presentation is to report the results of a study that investigated whether various communication tools and methods influence student learning process, learning outcomes, motivation, self-regulation and satisfaction. 2 Introduction The emergence of the newer web synchronous conferencing tools (e.g., Eluminate Live, Wimba Live (Contribute), WebEx, Saba Centra, and Adobe Connect) has provided the opportunity for high level of students to students and students to instructor interaction in web-based learning environments. The potential of these tools for providing interactive learning experiences that are closer to what is possible in face to face teaching and learning environments (Rourke, Anderson, Garrison,& Archer, 2001; Shi & Morrow, 2006) while simultaneously providing high levels of learner control, freedom of time and place make these tools the best viable option for distance education courses in general and online courses in particular. The use of web synchronous learning environments to provide interactive learning experiences for learners who participate in a variety of online classes has increased (Skylar, 2009; Stephens & Mottet, 2008) in recent years. In a survey study conducted by International Association for K-12 Online Learning (iNACOL, 2009) at 108 virtual schools, 47 percent of the responders reported that they had policies about frequency of contact through synchronous platforms (such as Elluminate, NetMeeting, Wimba). In another study, among the institutions offering online courses in 2006-2007, 31 percent reported that they offered the courses in a synchronous format; 19 percent used two-way video and audio (NCES, 2008). The inclusion of these relatively new online tools is an indication of how rapidly the field of online learning is changing and adapting to web synchronous conferencing tools. Research on online learning continues to support the importance of dialogue or interaction (defined as two-way communication among two or more people within a learning context (Gilbert & Moore, 1998)) between the teacher and students and among students for advancing the learning process and for internalizing the learning (e.g., Cavanaugh, 2005; Friend & Johnson, 2005; Offir, Lev & Bezale, 2008; Palloff & Pratt, 1999; Shale & Garrison, 1990; Zucker & Kozma, 2003). The importance of the interaction and its influence on the learning process in distance education is confirmed by Moore (1992,1993) in his model of transactional distance education (i.e., a physical separation that results in a psychological and communicative gap). Moore (1992) argues that increasing the interaction between learner and instructor results in a smaller transactional distance and more effective learning. Other studies also point that increased interaction results in increased student course satisfaction and learning outcomes (e.g., Chiu, Hsu, Sun, Lin & Sun, 2005; Lee, Tseng, Liu & Liu, 2007; Irani, 1998; Wang, 2003; Zhang & Fulford, 1994; Zirkin & Sumler, 1995). Two communication methods (i.e. synchronous and asynchronous) are used to engender high levels of student-student and student-teacher interaction in online learning environments. Using web conferencing tools, synchronous instruction brings teacher and students together simultaneously in virtual spaces while asynchronous instruction is delivered without any specific timetable using communication tools such as e-mail and discussion boards. Thus, the question is whether absence or presence of synchronous or live interaction will affect the learning processes and outcomes to the same extent for all learners with various characteristics (backgrounds, motivation and needs) and learning preferences, or whether other factors that compensate for the absence of the live interaction can be identified and accounted for deeper learning processes and for higher quality of learning outcomes. In addition, whether one can expect better understanding (integration and incorporation) of the learning materials for students who are taught by the synchronous distance education method than for students who are taught by the asynchronous intervention method (facilitated by media such as e-mail and discussion boards, supports work relations among learners and with teachers, even 3 when participants cannot be online at the same time), due to the limited live interaction in distance or online learning. Furthermore, regardless of availability of the newer Web-synchronous conferencing tools, our education system continues to offer online courses as separate units for distance students and live or blended courses for students who are able to attend classes live and in physical settings. Therefore, the power of the new Web-synchronous conferencing tools that combine ultra-high-definition video, quality audio, specially designed environment and interactive elements in order to create the feeling of being in person with students in distance locations are not utilized to bridge the separation between live and online learning environments. The Purposes of the Study The purposes of the present study were to (1) compare various communication methods (e.g., synchronous or live interaction; asynchronous or online interaction and a combined method of synchronous and asynchronous interaction) within a learning environment that combined live and online learning spaces to find out how they influence the learning process, learning outcomes, learner motivation, self-regulation and satisfaction, (2) identify factors that compensate for the absence of live interaction in online asynchronous environment and vice versa; (3) identify factors that can be accounted for deeper and higher quality of learning, and (3) assess the impact of various communication methods (synchronous, asynchronous and combined) on problem-solving skills (deep learning process), collaborative learning, learner motivation and self-regulation. Review of the Literature The review of the literature on the effect of the quality and level of interactions offered in various communications modes (i.e. synchronous and asynchronous) on student learning, satisfaction and motivation in online learning environment points to the following influencing factors: social and cognitive presence; immediacy of feedback; possibility of affective and interpersonal interactions; and the opportunity for learners to improve critical thinking, problem solving and communication skills. Social and Cognitive Presence The review of the literature on the advantages of asynchronous online learning environments, in general and asynchronous online interaction in particular points to several issues. First, asynchronous online learning environments provide the convenience and flexibility offered by the “anytime, anywhere” accessibility for interaction (Harasim, Hiltz, Teles & Turoff, 1995; Matthews, 1999; Jiang, 1998; Swan, Shea, Frederickson, Pickett, Pelz & Maher, 2000). Anywhere, anytime concept means that students can have access to courses discussion board and course materials 24 hours a day, regardless of location, making them more convenient than the live or synchronous learning environment (Berge, 1997; Harasim, 1990; Matthews, 1999; Simonson, Smaldino, Albright & Zvacek, 2000). Another advantage of asynchronous learning is that it allows students to reflect upon the materials and their responses before responding, unlike live interactions (Berge, 1997; Harasim, 1990; Matthews, 1999; Simonson, et. al, 2000). Furthermore, students also have the ability 4 to work at their own pace, which is especially important for those students who need more time to process information and learn the materials (Matthews, 1999; Simonson, et. al, 2000). However, many researchers who studied computer mediated communication (CMC) or asynchronous online interaction point to its limitation with regard to nonverbal and vocal communication and note that the inability of text-based asynchronous online discussion to transmit vocal and non-verbal cues (found in synchronous interaction) causes it to be less immediate, less intimate or colder and less personable experience. This feeling that is called “social presence” (Walther, 1992; Short, Williams, and Christi, 1979) postulate that a critical factor of a communication medium is its social presence. Social presence is defined as the “degree of salience of the other person in the (mediated) interaction and the consequent salience of the interpersonal relationships” (Short, et. al., 1979, p. 65). On the basis of this definition earlier studies argued that different communication media convey varying degrees of social presence based on their ability to transmit nonverbal and vocal information (Short et al, 1979). Thus, synchronous web interaction (e.g., audio and video) has the potential of having a higher degree of social presence compared with asynchronous interaction (e.g., text). However, later studies examined the degree to which a person is perceived as “real” in mediated communication questioned whether the attributes of a communication medium determined its social presence (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000; Gunawardena, 1995; Gunawardena & Zittle, 1997; Swan, 2003b; Walther, 1996). They argued that the learner’s personal perceptions of presence mattered more than the medium capabilities; therefore social presence could be a factor of both the medium and the communicators’ perceptions of presence in a sequence of interactions. Given this new construct, Gunawardena and Zittle (1997) further differentiated social presence and interaction, indicating that interactivity is a potential quality of communication that may or may not be realized by the individual. When it is realized and noticed by participants, there is “social presence.” Tu and McIssac (2002) also supported the reciprocal relation of interaction and social presence, noting that in order to increase the level of online interaction, the degree of social presence must also be increased. Supporting the same line of argument, Garrison (2003) argued that while social presence (personal and emotional connection presented in rich media) is essential for effective online interaction it is not enough for higher-order learning. He suggested that cognitive presence or the process of both reflection and discourse is necessary for achieving meaningful learning outcomes (Garrison, 2003). Garrison and his colleagues (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000) used this argument to develop a conceptual model for community inquiry in higher education. Their model identified three core elements of an educational experience that included social presence and two other concepts: cognitive presence, and teaching presence. Hence, researchers seem to agree that asynchronous online learning environments which provide the opportunity for both reflection and collaboration is more likely to shape cognitive presence in ways that are unique to this form of interaction. In sum, researchers seem to agree that social and cognitive presences are critical factors in building an interactive learning environment (Garrison, 2003) and when information is presented in a way that increases social presence, it is better remembered by learners and the learning process is considered more engaging (Homer, Plass, & Blake, 2008). However, the researchers do not appear to agree upon a single definition for social presence (Rettie, 2003; Tu, 2002). Furthermore, included 5 in the construct of social presence are concepts of immediacy and intimacy, which in turn influence social presence and level and quality of interaction. Immediacy and Intimacy Researchers argue that the two concepts of intimacy (Argyle & Dean, 1965) and immediacy (Wiener & Mehrabian, 1968) that are present in synchronous or live learning settings are related to social presence. Intimacy is defined as a function of eye contact, physical proximity, topic of conversation, etc. Changes in one function will produce compensatory changes in the others (Short, Williams, & Christie, 1976). A communication with maintained eye' contact, close proximity, body leaning forward, and smiling conveys greater intimacy (Burgoon, Buller, Hale, & deTurck, 1984). Thus, the interaction is likely to be unpleasant if behavior cannot be altered to allow an optimal degree of intimacy. Immediacy is the psychological distance communicators place between themselves and their recipients (Short et al., 1976). Immediacy, a concept proposed by Mehrabian (1971), refers to “physical and verbal behaviors that reduce the psychological and physical distance between individuals” (Baker, 2010, p. 4). Nonverbal immediacy behaviors include physical behaviors (e.g., leaning forward, touching another, looking at another’s eyes etc.), while verbal immediate behaviors are nonphysical behaviors (e.g., giving praise, using humor, using self-disclosure etc.). Immediacy also includes eye contact, smiling, vocal expressiveness, physical proximity, appropriate touching, leaning toward a person, gesturing, using overall body movements, being relaxed and spending time. The immediacy research points that verbally immediate behaviors can be conveyed in computermediated communication (O‟Sullivan, Hunt, & Lippert, 2004). Furthermore, research concludes that instructor immediacy is positively related to student cognition, affective learning and motivation (Arbaugh, 2001; Baker, 2004, 2010; McAlister, 2001), and that synchronous online instruction provide more immediacy than asynchronous communication alone (Haefner, 2000; Pelowski, Frissell, Cabral, & Yu, 2005). Collaborative Learning From a socio-cultural perspective, at the core of meaningful interaction is the concept of collaboration and co-construction, which involves all learners in the process of learning. Furthermore, researchers suggest that co-construction of ideas promotes greater ability for students to apply what they are learning (Chinn, O’Donnell, & Jinks, 2000; Roschelle, 1992). In order to build a learning community, meanings are to be jointly constructed as learners modify, confirm or discard their original ideas through hearing other points of views and referring to others’ experiences (Bakhtin, 1981; Chinn, Anderson, & Waggoner, 2001; Golden, 1986). Therefore, various communication methods for online learning should provide collaborative learning experiences at the convenience of the learner. Therefore, various communication methods (e.g., synchronous or live interaction; asynchronous or online interaction and a combined method of interaction) for online learning should provide collaborative learning experiences at the convenience of the learner. Since in a synchronous learning environment learners have access to visual and social cues and can offer comments at any time and without a prompt and change the conversation (Groenke, Maples, & Dunlap, 2005; Davidson-Shivers, Muilenberg, & Tanner, 2001; Herring, 1999) it is more likely that they can establish team work environment. 6 Motivation and Self-regulation There is much empirical evidence that self-regulated learning is of great importance for academic achievement (Zimmerman 1990; Zimmerman and Schunk 2001). Research also shows that students who reported using more self-regulatory strategies also reported higher levels of intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, and achievement (Pintrich & De Groot, 1990). From a constructivist perspective, selfregulated learning is defined as “an active, constructive process whereby learners set goals for their own learning and then attempt to monitor, regulate, and control their cognition, motivation, and behavior, guided and constrained by their goals and the contextual features in the environment” (Perry & Smart, 2002, p. 741). In other words, students are self-regulated to “the degree that they are metacognitvely, motivationally, and behaviorally active participants in their own learning process” (Zimmerman, 1986, p. 5). Thus, the concept and practice of self-directed and regulated learning have focused on issues of control, both externally and internally (Garrison, 2003). Garrison (1997) developed a model of self-directed learning that integrates motivation with issues of reflection and action. He identifies monitoring (reflection) and managing (action) the learning process as key dimensions of self-directed learning. According to this model, monitoring is learner’s assessment of feedback information, while managing is learner’s control of learning tasks and activities. Initiating interest and maintaining effort are also listed as being essential elements in self-direction and effective learning (Garrison, 1997). Without self- monitoring and self-management, learning effectiveness will be diminished considerably. Given this conceptualization, the issue of learner’s control is related to the concept of metacognition which has two essential features “self-appraisal and self-management of cognition” (Paris & Winograd, 1990, p. 17). Self-appraisal is “reflection about knowledge and motivational states for the purpose of resolving a problem, while selfmanagement is the metacognitive orchestration of actually solving a problem” (Garrison, 2003, p. 6). Researchers argue that the asynchronous and virtual nature of online learning provide better learning environment for learners to be self-directed and to take responsibility for their learning (practice selfregulation) (e.g., Garrison, 2003). In other words, in online learning environments learners have to assume greater control of monitoring and managing the cognitive and contextual aspects of their own learning. In addition, the learner's self-motivation increases as a result of self-regulatory attributes and self-regulatory processes in online learning (Eom, S. B. Wen, H. J. & Ashill N., 2006). In sum, some research studies seem to highlight the impact of online learning on student motivation and self-regulatory behaviors and students’ success in online learning when they are able to selfmotivate and self-regulate their own learning. What factors in various online communication methods influence student motivation and self-regulation is a question that needs further exploration. Technology Characteristics and Task Complexity Characteristics of technology tools can improve or hinder efficient delivery of instructional material (Alavi & Leidner, 2001). In online learning, technology characteristics are specifically linked to the communication features provided by the synchronous and asynchronous tools. The impact of different technology characteristics to present information and for communication may depend on task complexity (Tan & Benbasat, 1990; Tractinsky & Meyer, 1999). Brown et al. (1984) categorized tasks into three types ranging from easy, simple to difficult, and complex. Several different task characteristics have been alleged to affect performance through their influence on cognitive processes. Skehan (1998) identifies a task with a series of defining traits “a task is an activity in which meaning is primary; there is some kind of communication problem to solve; there is some sort of relationship to comparable real-world activities; task completion has some priority; 7 the assessment of the task is in terms of outcome” (p. 95). Swales’ (1990, p. 75) adds two more traits to the definition of task “differentiated” and “sequenceable.” Performance of a more complex task requires the learner to generate a more elaborate mental model (White & Frederiksen, 1990). Skehan & Foster (2001, p. 196) state that “task difficulty has to do with the amount of attention the task demands from the participants. Difficult tasks require more attention than easy tasks”. Hence, tasks that are more complex are associated with an increase in cognitive load, which can reduce performance and learning (Bannert, 2002; Sweller, vanMerrienboer, & Paas, 1998). Thus, higher level of interactivity captures the learner’s attention and increases user’s engagement with the task environment (Alessi & Trollip, 2001; Heinich et al., 1989). This results in deeper processing of the information, resulting in mastery of the information (Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989; Merrill, 1975), as well as aiding the individual in forming a personal mental model of the task (Wild, 1996). Thus, one can hypothesize that a learning environment such as the synchronous virtual classroom with a high level of interactivity and immediacy can aid in mental model creation, which helps in reducing the cognitive load and increasing learning and performance. When the task to be learned is complex, an interactive environment is important. Conceptual Framework Figure 1, Appendix A conceptualizes the online learning environment in this study and the factors that influences it. The framework has been used to design the study. It has also been used to guide the implementation of the study and its data collection and analysis procedure. As Figure 1 shows, the impact of a series of factors derived from the literature and others as they emerge are examined in the study. The framework also represents the three different learning environments under the study namely synchronous, asynchronous, and a combination of synchronous and asynchronous. In all the three environments, three types of interaction are examined. The visual also shows different outcomes that are targeted to be measured in the study. Methodology The study is designed to explore the following questions: How and in what ways can synchronous or live interaction, asynchronous or online interaction and a combined method of synchronous and asynchronous interaction influence students’ learning process, learning outcomes, motivation, self-regulation and satisfaction? What factors in various communication modes can be accounted for the effectiveness of interaction? What factors will impact the quality of learning, problem-solving (deep learning process) and collaborative skills, learner motivation and self-regulation? The exploratory nature of the study suggested a qualitative methodology, although quantitative data were also collected and analyzed in order to compare various communication methods and explore possible factors impacting interaction, quality of learning, collaboration, student motivation and selfregulation. As such, rather than just obtaining statistically significant results a comparative design was used as a basis for further exploration (Yin, 1994). 8 The Courses and their participants The conceptual framework was used to design and develop three modules/units of instruction (two weeks of instruction for each unit) for a graduate level course (three units) that is offered every spring semester during each academic year in the Instructional Technology program at a southeastern university. Data collected from the course in spring of 2011 and again in spring 2012. The spring semester graduate level course is a foundation course required of all students enrolled in the program. In order to enroll in this course, all students must have taken at least one foundation course in the program as a prerequisite and be familiar with the technology used for the delivery of courses in the program. Table 1 shows the design specifications for the three modules. Blackboard vista was used to deliver the course in spring of 2011 and Blackboard Learn was used to deliver the course in spring of 2012. A Synchronous Learning Management System (SLMS) (Horizon Wimba in spring 2011 and WebEx in spring 2012) was used for conducting real time discussion, group work and presentations. For synchronous delivery modules while all students used SLMS to communicate with each other and the instructor during real-time interaction, some students were also physically present in the classroom and had an opportunity to see each other face-to-face and through video feeds. Fourteen students (total 28) enrolled in each course. One of the researchers was also the instructor of record for the course. Students were assured of anonymity and were informed of their ability to choose not to participate at any time. According to demographic data, students were heterogeneous with regard to age, background and experience in both courses. All students participated in instruction of three units. The first unit was delivered asynchronously, the second unit was delivered synchronously and mixed method was used for the delivery of the third unit. The content and complexity of the units for all three modules/units were kept comparable. Course Design Specification A problem-based learning (PBL) or constructivist learning environment (Jonassen, 2008) was used as the instructional design model for both courses. The design specifications are summarized in Table 1. These specifications were used to keep the design of all modules consistent. Table 1: Design Specifications for the study Module 01 (Week 1 & 2) Module 02 (Week 3 and 4) Asynchronous Module Synchronous Module Students were assigned Students were assigned to to readings and other readings and other instructional materials instructional materials (e.g., (e.g., instructors’ lecture instructors’ lecture notes and notes and multimedia multimedia materials) a materials) a week earlier. week before live and synchronous meeting. Students then used module’s problem During live and synchronous solving team assignment class meeting, students to collaborate in participated in large group completing the discussion and/or a assignment. demonstration with lecture facilitated by the instructor. A small group discussion Module 03 (Week 5 and 6) Mixed Approach Students were assigned to readings and other instructional materials (e.g., instructors’ lecture notes and multimedia materials) a week earlier. Students were also assigned to a team and were instructed to begin discussing and collaborating with their teams on module’s problem-solving assignment using a small group discussion in the 9 area was created for each The large group discussion team as they worked on then was followed by their team assignments. breaking out into small teams. A large group discussion forum was created to Teams were assigned to provide opportunity for collaborate in completing interaction among all module’s problem-solving students and with the assignment during live and instructor. synchronous team meeting. Students were instructed Students were offered to not to meet continue team discussion in synchronously and just their designated virtual use asynchronous tools to rooms to follow up on live or communicate and to synchronous class and team complete their team discussion. However, assignments even if they Students were instructed to were in close proximity only use synchronous with each other. Students meetings for completing submitted and published team activities. their assignments to other The instructor also reviewed groups to review and students’ product and comment. collaborative process and offered feedback in The instructor also provided written synchronous or live meeting. feedback and comments In addition to oral comments on students’ team the instructor also provided products and written feedback on teams’ collaboration process. products and collaboration process. forum area. A large group discussion forum was created to provide opportunity for interaction among all students and with the instructor before live and synchronous class discussion. The asynchronous large and small group discussion was followed by a live and synchronous class and team meeting. During live and synchronous class meeting, students participated in large group discussion and/or a demonstration with lecture facilitated by the instructor. During live and synchronous class meeting, students participated in large group discussion and/or a demonstration with lecture facilitated by the instructor. The large group discussion was then followed by breaking out into teams to complete team assignment and present it for both peers’ and instructor’s review and comments. As with the previous modules, the instructor also provided written feedback and comments on students’ team product and collaboration process. Data Gathering Methods and Strategies Multiple sources of data were used to test the consistency of the findings and to examine various factors across different communication method. Table 2 summarizes data collection strategies and sources. 10 Table 2: Detail description of data collection strategies Data Gathering Methods Description and Strategies Student Satisfaction Student perception of quality of the interaction, learning experience and their degree of satisfaction was assessed at the end of each module using a 20 items questionnaire adopted from the literature. Student profile including At the beginning of each course and before the instruction students style of thinking and were asked to complete a profile form and take learning and learning thinking style inventories and post the results in the course forum discussion area under “get to know me” or similar thread. Student motivation and Student motivation and self-regulation skills were assessed at the self-regulation skills beginning and before intervention and then repeated at the end of each unit using 38 questions adopted from the literature (Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A. F., Garcia, T., & McKeachie, W. J., 1991). However, to triangulate the consistency of the results, student motivation and self-regulation skills were also assessed using observation of students’ behaviors using similar criteria drawn from the literature and responses to three reflective questions at the end of each module/unit. Social presence scale The Social Presence Scale developed by Gunawardena and Zittle (1997) was adopted and used to study the effectiveness of social presence in relationship to learning for each method of interaction or communication. Collaboration and The quality of students’ collaboration and communication was communication assessed using Tuckman’s group development model (1965). Students learning of the Students learning of the content and achievement of the objectives content and achievement were measured using a post-test for each module as well as the of the objectives products that student teams developed at the end of each module. Faculty perception and The faculty member kept a reflective log on workload, achievement reflection logs of learning objectives; quality of students’ products and ability to work collaboratively. Student postings, chat log All students’ postings in their personal spaces, team areas and large and audio archive of group discussion were downloaded and analyzed. In addition, the SLMS discussion archives of students’ synchronous discussion and asynchronous discussion logs were analyzed. Data Analysis Mixed methodology was used for data collection and data analysis. However, the overall design of the study was qualitative with focus on triangulation of various sources of the data to make conclusion. The constant comparison method was used to analyze different data sources for questions by cross-case grouping of answers (Patton, 1990). Results Table 3 summarizes student demographic information. As it is shown in Table 3, students were varied in their age and work experiences in both semesters. While 67% of students indicated 11 that they had not taken an online course that used synchronous communication tool before about the same percentage noted that they had taken online courses that had used asynchronous communication tools. Table 3: Student demographic data Question (N = 27) Had you taken an online course that used synchronous communication tools for interaction prior to enrolling in the program? Had you taken an online course that primarily used asynchronous communication (forum; e-mail) for interaction prior to enrolling in the program? How many classes have you taken in the MIT program? What is your age? What you gender? Indicate your prior college degrees. Indicate your prior work experience and number of years working. % Yes 33 % No 67 Yes 67 No 33 1-3 courses 22-30 31+ 42.4 53.6 Male Female 37 63 BS or BA MS 85 15 2-24 years of work experience Impact of various communication tools & methods on motivation and self-regulation The motivation and self-regulation survey was conducted prior to the first module and again at the end of each unit/module. The survey included 38 items (scale of 1-7; 1= not true of me, 7 = very true of me) and assessed intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, task value, control of learning, selfefficacy and self-regulation. The overall results did not show any significant difference between students’ motivation and self-regulation prior to the course and after each intervention. Students’ average score on four items measured Intrinsic motivation was high (M = 5.78 to 6.26) prior to the course and remained high at the end of each module. Students’ average score for 4 items measured extrinsic motivation was lower (M = 4.22 to 5.48) prior to the intervention and remained lower at the end of each module suggesting that students appeared to be more intrinsically motivated to learn the content of the course. The average score for six items measured task-value was high (M = 6.15 to 6.59) prior to the intervention and remained consistently high at the end of each module. This result was not surprising since the course is a required foundation course. The average score of four items measured control of learning was high (M = 5.70 to 6.33) prior to the intervention. However, the average score declined slightly at the end of module one or asynchronous learning approach (M = 4.96 to M = 5.96) but remained high for the other two intervention. The average scores for 8 items measured self-efficacy were high (M = 5.46 to 6.46) prior to the intervention and remained consistently high at the end of each module. The average scores for nine out of 12 items measured metacognitive or self-regulation skills were moderately high (M = 5.38 to 6.07) and remained high at the end of each module. However, while average scores for three items were moderate prior to the intervention (M = 4.08 (SD = 1.55); 4.96 (SD = 1.45) and 4.15 (SD = 1.88)), they changed slightly at the end of each module. The average scores for the item: “During class time I often miss important points because I am thinking of other things,” deceased at the end of module one (asynchronous 12 only; M = 3.91 (SD = .97)) and module two (synchronous only; M = 3.96 (SD = 1.60)), but increased at the end of module three (mixed method; 4.23 (SD = 1.27)). Similar change was observed for the item “I often find that I have been reading for class but don’t know what it was all about,” (M = 4.91 (SD (.94); 4.96 (SD = 1.14); M = 5.00 (SD = 1.45). Average scores for the third item “I often find that I have been reading for class, but don’t know what it was all about” however, increased slightly. In sum, the comparative results of motivation and self-regulation survey did not show significant changes. Minor changes were observed in a few items in the category of selfregulation in favor of mix methodology. Results of motivation and self-regulation survey were cross-examined using the instructor’s observation notes. The observation notes for both semesters confirmed that students were highly motivated at the beginning of the semester, as it was evidenced by their enthusiasm for reading and discussing the content and completing team activities. In their communication students also noted that previous students had told them about the importance of the course content in their future success. Furthermore, having had a positive learning experience in their previous course with the same instructor appeared to have an impact on student motivation and self-regulation skills, as they seemed to be familiar with the teaching strategies. Cross examination of students’ responses to the end of each intervention reflective questions combined with instructor’s observation notes, however, indicated that some students appeared to have much harder time staying on tasks and regulating their activities during asynchronous intervention (completing readings and taking notes, posting in the discussion area and contribute to the team discussion) while others seemed to became more anxious in spite of reading and keeping summary notes because they were worried that they might have missed or misunderstood some concepts and expressed their concerns in the discussion area (e.g., “. . . feel somewhat lost, because the asynchronous format lacks a live lecture of the material . . . “; “My worry is that I’m not getting the whole picture.”; “I had a really hard time understanding the information this week (which is bad since it’s the first week!.”; “Enjoyed the flexibility in my schedule, however, did struggle with the content "on my own."; “I feel that I would be more successful if I had been guided a little more with some reinforcement to the reading.”). Students’ responses to the reflective questions at the end of module one indicated that instructor’s opening and closing remarks, participation in the discussion forum and her lecture notes and slides did not seem to ease some students’ doubts about whether or not they had good understanding of the materials. Analysis of students’ learning and thinking styles surveys in relation to students’ patterns of behavior (reading and summarizing materials, posting in the discussion area and contributing to the team discussion) showed that students who were active, verbal and sequential learners had much harder time regulating their learning compared with reflective, visual, and global learners. Reflective learners indicated that they enjoyed reading and pondering on their own although they also mentioned that they missed live discussion and lectures (e.g., “. . . made me really think about readings and ponder my own conclusions.”; “. . . it was nice to have more time to read and work on assignments.”; “The biggest advantage for me was that I actually read a lot more from the texts and had to create my own levels of understanding. "think" it stunk.” ; “Without the interaction and discussion, I found that I had to re-read the materials for better understanding and try to answer my own questions.”). Impact of various communication tools and methods on social presence 13 A 12 item questionnaire (Gunawardena and Zittle (1997) was used to measure students’ reaction to social presence factor (scale of 1 to 5, 1 = very unsatisfied, 5 = very satisfied). The scale has been used in many studies of online courses with undergraduate and graduate students (e.g., Richardson & Swan, 2003; Skiba, Holloway, & Springer, 2000). The adopted scale assessed three categories of social presence (affective, interactive and cohesive). Table 4, summarizes each category and its behavioral indicators. Table 4: Categories and Indicators of Social Presence Categories Indicators Expression of emotions Affective CMC conveys feeling and emotion, Use of humor and the language used in CMC is Self-Disclosure stimulating, expressive, meaningful and easily understood. Continuing a thread Interactive two-way exchanges, immediacy Quoting from other messages CMC as pleasant, immediate, Referring explicitly to other messages responsive and comfortable when Asking questions dealing with familiar topics Complimenting, expressing appreciation, expressing agreement Vocatives Cohesive Addresses or refers to the group using inclusive pronouns Phatics / Salutations The social presence average scores for some items were consistently lower for module one (asynchronous only) and higher for mixed method. For instance, students scored the item “the communication used in this unit was an excellent medium for social interaction” lower (M= 2.46) for asynchronous only module, higher (M = 3.78) for synchronous only and much higher for mixed method (M = 4.65). Similar trend was also observed for the following items “I felt comfortable conversing through this unit’s medium” or “I felt comfortable participating in the discussion.” However, the items that measured instructor’s social presence seemed to show minor differences across three modules. For instance the average scores for following items “The instructor(s) created a feeling of community” and “the instructor facilitated discussion in the module” were 4.00, 4.08, 4.33 for module 1 to 3. Overall, the average scores for mixed method were higher and were above 4.15 indicating higher social presence in mixed communication method. Students’ responses to the end of modules’ reflective questions confirmed students’ positive feeling toward their interaction with their peers and the instructor. Three themes that emerged from students’ narrative responses to reflective questions that were related to social presence were “relationship,” “communication difficulty,” and “immediate feedback.” These factors appeared to impact students’ perception of social presence. Table ?? provide excerpts for each theme. Without the interaction and discussion, I found that I had to re-read the materials for better understanding and try to answer my own questions. 14 Communication Difficulty “I thought that it is very difficult to fully express my thoughts [in] writing without being able to actually speak to my group members.” “Schedules made it tougher b/c you had to "wait" for others to respond or they had to wait on you.” . . .not be able to talk with classmates immediately about the readings; having to write out thoughts in the discussion board without first discussing it in class. “ “. . .having to wait for others slowed me down. In all, it was counterproductive.“ “I was forced to rely more on my own ideas and opinions as I didn't have the advantage of turning to my classmates. “ Impact of various communication tools & methods on immediacy Immediacy or verbal and non-verbal behaviors that reduce the psychological and physical distance between individuals was measured with a 34 item survey (scale of 1 to 5, 1 = very unlikely, 5 = very likely). Twenty items measured verbal communications while 14 items measured nonverbal communications. The results showed no significant difference across three types of communication methods. Average scores were consistently moderate to high for all three interventions. This result could be due to students’ familiarity with the instructor’s communication styles. It could also be related to course design specifications and the fact that the students had constant communication with their peers and the instructor to accomplish weekly activities despite communication tools. Impact of various communication tools & methods on student satisfaction Student satisfaction was measured at the end of each intervention using 20 item questionnaire (scale of 1 to 5, 1 = very unsatisfied, 5 = very satisfied). The results point to some differences in students’ satisfaction. While in none of the interventions students showed their dissatisfaction with any of the items students’ responses showed highest level of satisfaction for the following items at the end of the first intervention (Asynchronous only): “It is easy to contact the instructor,” “overall, the instructor of the course acknowledged student participation in the course (for example replied in a positive, encouraging manner to student submissions),” “If I have an inquiry, the instructor finds time to respond,” “The instructor encourages my participation” at the end of the first intervention (Asynchronous only). However, while high level of satisfaction for some items remained the same at the end of second intervention (synchronous only) (e.g., “If I have an inquiry, the instructor finds time to respond,”) students were highly satisfied with different set of items (“I work with others,” I collaborate with other students in the class,” and “Group work is a part of my activities.”). Interestingly enough, students’ satisfaction was steady across all items at the end of the third intervention (combined method). Students’ responses to the reflective questions at the end of each 15 intervention provided some explanations for these results. However, more specific and detail quantitative analysis is under way to make a better sense of the results. References Arbaugh, J. B. (2001). How instructor immediacy behaviors affect student satisfaction and learning in web-based courses. Business Communication Quarterly, 64(4), 42-54. Baker, C. (2010). The Impact of Instructor Immediacy and Presence for Online Student Affective Learning, Cognition, and Motivation. The Journal of Educators Online, 7(1), 1-30 Baker, J. D. (2004). An investigation of relationships among instructor immediacy and affective and cognitive learning in the online classroom. The Internet and Higher Education, 7(1), 1-13. Baker, J. D. (2010). The Impact of Instructor Immediacy and Presence for Online Student Affective Learning, Cognition, and Motivation. The Journal of Educators Online, 7(1), 1-30. Berge, Z.L. (1997). Computer conferencing and the online classroom. International Journal of Educational Telecommunications, 3 (1). Cavanaugh, C. (2005). Virtual Schooling: Effectiveness for Students and Implications for Teachers. In C. Crawford et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education International Conference (301-308). Chesapeake, VA: AACE. Friend, B., & Johnston, S. (2005). Florida Virtual School: A choice for all students. In Z. L. Berge & T. Clark (Eds.), Virtual schools: Planning for success (pp. 97-117). New York: Teachers College Press. Gilbert, L., & Moore, D. R. (1998). Building interactivity into web courses: Tools for social and instructional interaction. Educational Technology, 38(3), 29-35. Gunawardena, C.N. & Zittle, F.J. (1997). Social presence as a predictor of satisfaction within a computer-mediated conferencing environment. The American Journal of Distance Education, 11(3), 8-26. Haefner, J. (2000). Opinion: The importance of being synchronous. Academic.writing . Retrieved Oct. 5, 2010 [http://wac.colostate.edu/aw/teaching/haefner2000.htm]. Harasim, L.M. (1990). Online education: Perspectives on a new environment. New York: Praeger. Harasim, L.N., Hiltz, S.R., Teles, L., and Turoff, M. (1995). Learning networks: A field guide to teaching and learning online. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. International Association for K-12 Online Learning (iNACOL, 2009). Committee Issues Brief: Examining Communication and Interaction in Online Teaching. iNACOL, retrieve on Sept. 2010 [http://www.inacol.org/research/docs/NACOL_QualityTeaching-lr.pdf]. 16 Irani, T. (1998). Communication potential, information richness and attitude: A study of computer medicated communication in the ALN classroom. ALN Magazine, 2(1). Jiang, M. (1998). Distance Learning in a Web-based Environment. (Doctoral dissertation, University at Albany/SUNY, 1998). UMI Dissertation Abstracts, No. 9913679. Matthews, D. (1999). The origins of distance education and its use in the United States. T.H.E. Journal, 27 (2), 54-66. McAlister, G. (2001). Computer-mediated immediacy: A new construct in teacher-student communication for computer-mediated distance education (Doctoral dissertation, Regent University, 2001). Dissertation Abstracts International, 62, 2731. Moore, M. (1993). Theory for transactional distance. In D. Keegan (Ed.), Theoretical principles of distance education (pp. 22–38). London, New York: Routledge. Moore, M. (1993). Theory for transactional distance. In D. Keegan (Ed.), Theoretical principles of distance education (pp. 22–38). London, New York: Routledge. National Center for Educational Statistics (2008, December). Distance education at degreegranting postsecondary institutions: 2006-07. Retrieved Sept. 2010, from http://www.nces.ed.gov/pubs2009/2009044.pdf. Offir, B., Lev, Y. & Bezale, R. (2008). Surface and deep learning processes in distance education: Synchrnous versus asynchronous systems. Computers & Education, 51, 1172-1183. Available online [www.sciencedirect.com]. O‟Sullivan, P. B., Hunt, S. K., & Lippert, L. R. (2004). Mediated immediacy: A language of affiliation in a technological age. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 23(4), 464-490. Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (1999). Building learning communities in cyberspace. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Pelowski, S., Frissell, L., Cabral, K., & Yu, T. (2005). So far but yet so close: Student chat room immediacy, learning, and performance in an online course. Journal of Interactive Learning Research, 16, 395-407. Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 33-40. Rettie, R. (2003). Connectedness, awareness, and social presence. Paper presented at the 6th International Presence Workshop, Aalborg, Denmark. Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. (2003). Examining social presence in online courses in relation to students' perceived learning and satisfaction. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 7(1), 68-88. Richardson, J. C., & Swan, K. (2003). Examining social presence in online courses in relation to students' perceived learning and satisfaction. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 7(1), 6888. 17 Rourke, L., Anderson, T., Garrison, D. R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing social presence in screen text-based computer conferencing. Journal of Distance Education, 14 from http://cade.athabascau.ca/vol14.2/rourke_et_al.html Rourke, L., Anderson, T., Garrison, D.R., and Archer, W. (2001). Assessing social presence inasynchronous text-based computer conferencing. Journal of Distance Education, 14 (2). Russo, T., & Benson, S. (2005). Learning with invisible others: Perceptions of online presence and their relationship to cognitive and affective learning. Educational Technology & Society, 8(1), 54-62. Shale, D., & Garrison, D. R. (1990). Introduction. In D.G.D.R. Shale (Ed.), Education at a distance (pp. 1-6). Malabar, FL: Robert E. Kriger. Shea, P. J., Fredericksen, E., Pickett, A., Pelz, W., & Swan, K. (2001). Measures of learning effectiveness in the SUNY learning network. In J. Bourne & J. C. Moore (Eds.), Online education, volume 2: Learning effectiveness, faculty satisfaction, and cost effectiveness (pp. 31 54). Needham, MA: SCOLE. Shi, S., & Morrow, B., V. (2006). E-Conferencing for instruction: What works? EDUCAUSE Quarterly, 29(4), 42-49. Short, J., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The social psychology of telecommunications. London: John Wiley & Sons. Simonson, M., Smaldino, S., Albright, M., and Zvacek, S. (2000). Teaching and Learning at Distance: Foundations of Distance Education. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill. Skiba, D. J., Holloway, N. K., & Springer, H. (2000). Measurement of best practices and social presence in web-based international nursing informatics pilot course. Nursing Informatics 2000: Proceedings of the 7th IMIA International Conference on Nursing, 650-657. Skylar, A. A. (2009). A comparison of asynchronous online text-based lectures and synchronous interactive web conferencing lectures. Issues in Teacher Education, 18(2), 69-84. Skiba, D. J., Holloway, N. K., & Springer, H. (2000). Measurement of best practices and social presence in web-based international nursing informatics pilot course. Nursing Informatics 2000: Proceedings of the 7th IMIA International Conference on Nursing, 650-657. So, H. J., & Brush, T. A. (2007). Student perceptions of collaborative learning, social presence, and satisfaction in a blended learning environment: Relationships and critical factors. Computers & Education. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2007.05.009. Stephens, K. K., & Mottet, T. P. (2008). Interactivity in a web conference training context: Effects on trainers and trainees. Communication Education, 57(1), 88-104. Swan, K. (2003a). Developing social presence in online course discussions. In S. Naidu (Ed.), Learning and teaching with technology: Principles and practices (pp. 147-164). London: Kogan Page. 18 Swan, K. (2003b). Learning effectiveness online: What the research tells us. In J. Bourne & J. C. Moore (Eds.), Elements of quality online education, practice and direction (pp. 13-45). Needham, MA: Sloan Center for Online Education. Swan, K., Shea, P., Frederickson, E., Pickett, A. Pelz, W., and Maher, G. (2000). Building knowledge building communities: Consistency, contact, and communication in the virtual classroom. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 23 (4), 389-413. Tu, C.-H. (2000). On-line learning migration: From social learning theory to social presence theory in a CMC environment. Journal of Network and Computer Applications, 2, 27-37. Tu, C.-H. (2002). The measurement of social presence in an online learning environment. International Journal on E-Learning, April-June, 34-45. Tuckman, Bruce W. (1965) 'Developmental sequence in small groups', Psychological Bulletin, 63, 384-399. The article was reprinted in Group Facilitation: A Research and Applications Journal - Number 3, Spring 2001 and is available as a Word document: http://dennislearningcenter.osu.edu/references/GROUP%20DEV%20ARTICLE.doc. Accessed Oct. 14, 2010. Zucker, A., & Kozma, R. (2003). The virtual high school: Teaching generation V. New York: Teachers College Press. 19 Appendix A Table 1: Design Specifications for the study Module 01 (Week 1 and 2) Asynchronous Module Students were assigned to readings and other instructional materials (e.g., instructors’ lecture notes and multimedia materials) a week earlier. Students then used module’s problem-solving team assignment to collaborate in completing the assignment. A small group discussion area was created for each team as they worked on their team assignments. A large group discussion forum was created to provide opportunity for interaction among all students and with the instructor. Students were instructed not to meet synchronously and just use asynchronous tools to communicate and to complete their team assignments even if they were in close proximity with each other. Students submitted and published their assignments to other groups to review and comment. The instructor also provided written feedback and comments on students’ team products and collaboration process. Module 02 (Week 3 and 4) Synchronous Module Students were assigned to readings and other instructional materials (e.g., instructors’ lecture notes and multimedia materials) a week before live and synchronous meeting. During live and synchronous class meeting, students participated in large group discussion and/or a demonstration with lecture facilitated by the instructor. The large group discussion then was followed by breaking out into small teams. Teams were assigned to collaborate in completing module’s problem-solving assignment during live and synchronous team meeting. Students were offered to continue team discussion in their designated virtual rooms to follow up on live or synchronous class and team discussion. However, Students were instructed to only use synchronous meetings for completing team activities. The instructor also reviewed students’ product and collaborative process and offered feedback in synchronous or live meeting. In addition to oral comments the instructor also provided written feedback on teams’ products and collaboration process. Module 03 (Week 5 and 6) Mixed Approach Students were assigned to readings and other instructional materials (e.g., instructors’ lecture notes and multimedia materials) a week earlier. Students were also assigned to a team and were instructed to begin discussing and collaborating with their teams on module’s problem-solving assignment using a small group discussion in the forum area. A large group discussion forum was created to provide opportunity for interaction among all students and with the instructor before live and synchronous class discussion. The asynchronous large and small group discussion was followed by a live and synchronous class and team meeting. During live and synchronous class meeting, students participated in large group discussion and/or a demonstration with lecture facilitated by the instructor. During live and synchronous class meeting, students participated in large group discussion and/or a demonstration with lecture facilitated by the instructor. The large group discussion was then followed by breaking out into teams to complete team assignment and present it for both peers’ and instructor’s review and comments. As with the previous modules, the instructor also provided written feedback and comments on students’ team product and collaboration process. 20 Table 2: Detail description of data collection strategies Data Gathering Methods and Strategies Student questionnaire Student profile including style of thinking, learning and problem solving and collaborative learning skills Student motivation and self-regulation skills Social presence scale Collaboration and communication Students learning of the content and achievement of the objectives Faculty perception and reflection logs Student postings, chat log and audio archive of SLMS discussion Description Student perception of quality of the interaction, learning experience and their degree of satisfaction was assessed at the end of each module using a questionnaire in which students respond to a list of questions (both open ended and closed-ended items) about the course design specifications. At the beginning of each course and before the instruction students were asked to complete a profile form and take learning and thinking style inventories and post the results in the course forum discussion area under “get to know me” or similar thread. Student motivation and self-regulation skills were assessed at the beginning and at the end of each course using a series of questions adopted from the literature. However, to triangulate the consistency of the results, student motivation and self-regulation skills were also assessed using observation of students’ behaviors using a set of criteria drawn from the literature and responses to three reflective questions. The Social Presence Scale developed by Gunawardena and Zittle (1997) was adopted and used to study the effectiveness of social presence in relationship to learning for each method of interaction or communication. The scale has been used in many studies of online courses with undergraduate and graduate students (e.g., Richardson & Swan, 2003; Skiba , Holloway, & Springer, 2000). The Social Presence Scale consisted of fourteen items that embody the concept of “immediacy” as defined in Short, et al. (1976). Modification of the wording of the scale was made as needed to adjust it to the courses content. Permission was obtained from Gunawardena to make these minor modifications and use the scale. The quality of students’ collaboration and communication is assessed using Tuckman’s group development model (1965). Students learning of the content and achievement of the objectives were measured using post-test for each module as well as the products that student teams developed at the end of each module. The faculty member kept a reflective log on workload, achievement of learning objectives; quality of students’ products and ability to work collaboratively. All students’ postings in their personal spaces, team areas and large group discussion were downloaded and analyzed. In addition, the archives of students’ synchronous discussion and asynchronous discussion logs were collected and analyzed. 21 Figure 1: The conceptual framework for the study