D must have an intention to permanently deprive

advertisement

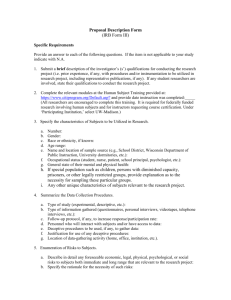

Criminal Law Mini Exam Notes 1 Contents 2 Basic bits ....................................................................................................................................2 2.1 Burden of proof ............................................................................................................................. 2 2.2 Doli Incapax ................................................................................................................................... 2 3 Larceny ......................................................................................................................................3 3.1 Statute:.......................................................................................................................................... 3 3.2 Common Law ................................................................................................................................ 3 4 Larceny by finding ......................................................................................................................8 5 Assault .......................................................................................................................................9 5.1 Types of injury ............................................................................................................................... 9 5.2 Common Assault (s61) ................................................................................................................ 10 5.3 Aggravated Assaults ................................................................................................................... 11 5.4 Mitigating factors ....................................................................................................................... 12 6 Sexual Assault .......................................................................................................................... 13 6.1 Elements ...................................................................................................................................... 13 6.2 Offenses ...................................................................................................................................... 13 6.3 Definition of “sexual intercourse” (s61H) .................................................................................... 13 6.4 Consent (s61HA) .......................................................................................................................... 14 6.5 Mens Rea..................................................................................................................................... 15 7 Attempt ................................................................................................................................... 16 7.1 Actus reaus .................................................................................................................................. 16 7.2 Mens Rea..................................................................................................................................... 16 8 Joint Criminal Enterprises ......................................................................................................... 17 8.1 Doctrine of common purpose ...................................................................................................... 17 8.2 Offenses ...................................................................................................................................... 17 9 Defences .................................................................................................................................. 18 9.1 Automatism................................................................................................................................. 18 9.2 Insanity ........................................................................................................................................ 18 9.3 Intoxication ................................................................................................................................. 20 9.4 Self-Defence ................................................................................................................................ 21 9.5 Duress.......................................................................................................................................... 22 9.6 Necessity ..................................................................................................................................... 23 Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 1 2 Basic bits 2.1 Burden of proof The burden of proof falls to the prosecution in proving all charges beyond reasonable doubt Woolmington v Director of Public Prosecutions [1935]. With the defenses, the burden shifts to the defense, where they have to raise it as an issue (i.e. for provocation or insanity) or prove that it is reasonable, and the Prosecution must negative it beyond all reasonable doubt. 2.2 Doli Incapax If the defendant is below the age of ten, they cannot form the mens rea (Children (Criminal Proceedings) Act 1987 (NSW) s5)) Between the ages of ten and 14, there is a rebuttable presumption of doli incapax (R (a child) v Whitty (1993)) Any defendant under the age of 17 may be tried in a childrens court (Children's Court Act 1987 (NSW)) Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 2 3 Larceny 3.1 Statute: S117 Crimes Act 1900 Whosoever commits larceny […] shall, except in cases hereinafter otherwise provided for, be liable to imprisonment for 5 years. This leaves the definition of larceny to the common law, only stipulating the punishment. 3.2 Common Law Ilich v R (1987) At common law, larceny is committed by a person who: Acts Reus Mens Rea Takes and carries away With intent to permanently deprive the owner Anything capable of being stolen And without a claim of right made in good (property; owned by another) faith Without the consent of the owner Fraudulently With temporal coincidence 3.2.1 3.2.2 Takes and carries away Asportation physical removal of property (even the smallest movement will suffice) (Lapier (1784))[trying to remove earring, earring became entangled; held: this satisfied asportation] Must be a positive act (Thomas (1953)) Property capable of being stolen Property must be tangible (Perry (1845)) Property must have value (even tiny value is sufficient) (R v Morris (1840)) Intangible goods, patents, copyrights and trademarks cannot be stolen Land cannot be stolen; squatters prosecuted for trespass under Enclosed Lands Protection Act 1901 (NSW) s4 Crimes Act 1900 (NSW), s4 "Property" includes every description of real and personal property; money, valuable securities, debts, and legacies; and all deeds and instruments relating to, or evidencing the title or right to any property, or giving a right to recover or receive any money or goods; and includes not only property originally in the possession or under the control of any person, but also any property into or for which the same may have been converted or exchanged, and everything acquired by such conversion or exchange, whether immediately or otherwise. Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 3 3.2.3 In someone else’s possession Property must be in someone else’s possession to be able to be stolen (DPP v Brooks (1974))[one has in one’s possession whatever it is, to one’s knowledge, physically in one’s custody and under one’s control]. Actual Possession o immediate and direct physical control over property, with intention (knowledge) to possess (Moors v Burke) o person does not have to know of property to own it (Hibbert v McKiernan (1948))[golf course with golf balls, place/number unknown; held: possession was satisfied] Constructive Possession (Ellis v Lawson) [Shop assistant, friend stole radio; held: owner still had constructive possession of the radio as he had not consented to the radio’s removal] o having the power and intention to have and control property but without direct control or actual presence upon it (Ellis v Lawson) Control satisfies “belonging” (Harding (1929)) o “Manual custody or exclusive right to place his hands on it […] have manual custody whenever he wishes (Moors v Burke (1919)) Abandoned property cannot be stolen (Donogue v Coombe (1987)) If property is not in someone’s possession, it can still be stolen if it is owned (Flood) Property may be owned by more than one person, since control, ownership and possession are not mutually exclusive (Anic (1993)). Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 4 3.2.4 Without the consent of the person in possession To satisfy larceny, property must have been taken w/o consent (Croton (1967))/against the will of the person in possession (Davies (1970)). Thus, consent nullifies this offense. 3.2.4.1 Facilitation =/ consent, question of fact to differentiate between them. Kennison v Daire (1986) [Facilitation] Guy took money out of an ATM by a card that was invalid. ATM “facilitated” this transaction Held: this did not amount to consent by the bank; the machine could not consent for the bank. Turvey (1946) [Consent] Guy planned on stealing Boss found out Boss allowed him to steal to entrap him Held: He did not carry goods away against the will of the owner Martin v Puttick (1968) [Facilitation] Chick stole, put stuff in shopping bag and gave stuff to manager, who returned it to her Held: she did not give over her constructive possession to the manager, and thus returning the bag was not consent 3.2.4.2 Threats Consent because of threats can be nullified (Lovell (1881)). Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 5 3.2.4.3 Consent due to a mistake Question is: Should D be held criminally liable for V’s mistake? Unilateral mistake o D is aware of the mistake at the time Mutual mistake o D subsequently becomes aware Potisk (1973) Not binding, merely “cogent” Bank teller used the wrong exchange rate, gave too much money Bank teller knew how much money he had given D did not realize until after he had left (unilateral mistake) Held: Where V consented to handing over property due to a mistake, =/ larceny, because handing over was with consent Ilich (1987) [authority] Persuasive, since high court decision based on SA law which does not require absence of consent D was overpaid by employer D put overpaid amount aside Consent had not been induced by fraud; mistake had not prevented property passing to D Held: unilateral or mutual mistake only negate consent if the mistake is so fundamental so as to prevent ownership from passing; can occur three ways: Mistake as to the identity of the person to whom property was given (as per Middleton (1873) [post office, unilateral mistake, mistaken identity]) Mistake as to the identity of what is being handed over (as per Ashwell (1885) [soverign rather than shilling given, was larceny]) Excess quantity of goods is delivered, ownership of excess not transferred (Russell v Smith (1958)) Ilich on money: Excluded from fundamental mistake; mistake of quantity is not a fundamental mistake Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 6 3.2.5 Intent to permanently deprive D must have an intention to permanently deprive (Foster (1967)). 3.2.5.1 Conditional return E.g. took, pawned, re-bought after pay; does not nullify mens rea Crimes Act 1900 (NSW), s118 “Intent to return property no defence” Where, on the trial of a person for larceny, It appears that the accused appropriated the property in question to the accused’s own use, or for the accused’s own benefit, or that of another, but intended eventually to restore the same, or in the case of money to return an equivalent amount, such person shall not by reason only thereof be entitled to acquittal. However, this is limited by Foster (1967) to cases where D appropriated property “with an intention to take ownership of the goods, to deal with them as his own”; not where D has merely “the intention to deprive the true owner of the possession for a limited time”. Foster (1967) D borrowed V’s pistol to show parents Said he was to return pistol Did not exercise ownership (like “conversion”) Held: =/ larceny 3.2.5.2 Altered Condition When condition of good is altered, there is larceny (Duru (1973)) [was going to return checks after they had been banked, was still larcenous as their value was drastically reduced]; this alteration of goods must be drastic, not part of normal use of the item (Bailey (1924)) [using petrol when borrowing a car held not to be larcenous]. 3.2.5.3 Joyriding Under s154A, joyriding does not require intention to permanently deprive; only requiring lack of consent to charge. 3.2.5.4 Fungibles/Commodities Replacing with “like”/“equivalent” objects can still be larcenous (as the object, rather than the value, is the subject of the law); in cases of borrowing from a till, larceny can be charged since exact notes are not to be returned (Cockburn (1986)). If V knows of the transaction, such as a loan, actus reus is not satisfied, since he would intend to transfer ownership. Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 7 3.2.6 Without a claim of right made in good faith A legal claim of right negates any mens rea (Fuge (2001)); a moral right is insufficient (Harris v Harrison (1963)). Mistake of law (i.e. D though that he had a legal right to the good) prevents mens rea from forming (Lopatta (1983)) [was owed money, stole oil worth the same amount; held: prosecution had to negate beyond reasonable doubt the possibility of D honestly believing he had a claim of right, the reasonableness of this belief is irrelevant]. Claim of right must be to full extent of the property taken (i.e. not a defense if you took more than you were owed) (Astor v Hayes (1988)) [claim of right to handbag, not contents]. 3.2.7 Fraudulently = dishonesty; question of fact (Feely (1973))UK (Peters (1998))as applied in NSW “intentional creation of a situation [where D,…]knowing that he has no right to deprive [does so]”. 3.2.8 Temporal Coincidence Normal temporal coincidence (Thurdbon (1849)) extended by the Riley (1853) principle: where the original taking is innocent, and D later forms intent to permanently deprive, Larceny is a continuing trespass, and temporal coincide is satisfied. This principle is limited by the doctrine of continuing trespass, that is, the original taking must be trespassory for the Riley principle to extend this trespass to allow for extended temporal coincidence. Butle (1960) [farmer herds in extra sheep, later kills them, originally lacked mens rea, but original act was trespassory, thus subsequent formation of mens rea satisfied temporal coincidence]. Davies (1970) [D bought car, car was stolen, D didn’t know originally. D found out, kept the car. Held: would have been trespass, but D had the consent of the person in possession]. 4 Larceny by finding If D picks up property with the intent of finding the ownder, the taking is not trespassory MacDonald (1983). D must make a reasonable effort to find the owner (MacDonald (1983)) [Camera, not asking enough questions] (Thurbon (1849)) [found banknote, did not know owner, later found out the owner and did not return]. D can, after trying to find V and failing, later appropriate the property (Matthews (1873)). Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 8 5 Assault Classified by level of injury (trifling harm (s61), ABH (s59), wounding (s33, 35), GBH (s33, 35)). Murder/Homicide Assault occasioning GBH • Intent (s33) • Reckless (s35) • Nelgigent (s54) Wounding with intent (s33) •Recklessly (s35) Assault occasioning ABH (s59) Common Assault (s61) •With contact •Without contact 5.1 Types of injury Actual bodily harm (R v Donovan [1934]) o Any hurt or injury calculate to interfere with the health or comfort of the victim o More than transient and trifling Wounding (R v Devine (1982)) o 2 layers of skin, i.e. penetrates the epidermis and reaches the dermis Grievous bodily harm o Bodily harm of a really serious kind (DPP v Smith (1961)) o In s4 (definitions) Destroying a foetus (outside of medicine) Permanent or serious disfiguring Any grievous bodily disease Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 9 5.2 Common Assault (s61) 5.2.1 Battery Fagan (1969) Actus reus o Application of unlawful contact o w/o consent of V Mens rea o Intention to apply unlawful contact; OR, o Recklessly applies unlawful contact (MacPherson v Brown (1975)) Test for recklessness is “possibility rather than probability” Test is subjective) Temporal Coincidence 5.2.2 Assault Darby v DPP (2004) Actus reus o Threatened application of unlawful contact Omission cannot be an assault o V apprehends a threat of unlawful contact o V apprehends that the unlawful contact is imminent (Zanker) Threat of future violence is generally not assault (Knight (1988)) Telephone + (Ireland) Conditional threats Does D have a right to impose the condition (Rosza v Samuels) Words of the threat (did D wish to impose apprehension) (Tuberville v Savage) Mens Rea o Intentionally creating an apprehension of imminent unlawful contact; OR, o Recklessly does so (as per battery) Temporal coincidence Ability to execute threat is irrelevant, just V’s perception of D’s ability to execute threat (Everingham (1949)). Zanker (1988) In car Refused sex “my friend will fix you up” Could not leave care Held: immideate and continuing fear Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 10 5.3 Aggravated Assaults NB: the precedent in Royall allows us to extend psychic assaults to these. 5.3.1 Aggravated assault with actual bodily harm (s59) There is no mens rea requirement to want to cause ABH, merely to assault Ss(1) assaults … w ABH Ss(2) in company 5.3.2 Reckless GBH or wounding (s35) Ss(1) reckless GBH in company Ss(2) reckless GBH Ss(3) Reckless wounding in company Ss(4) Reckless wounding 5.3.3 Wounding or GBH with intent (s33) Additional mens rea requirement Ss(1) Wound or GBH with intent to GBH is prosecuted under this section 5.3.4 Negligent GBH (s54) Must be by unlawful or negligent act (s54); negligence is proved to the criminal standard (a high degree of negligence) (Newman (1948)). 5.3.5 Assault w intent to kill (s27) Whosoever administers to, or causes to be taken by, any person any poison, or other destructive thing, or by any means wounds, or causes grievous bodily harm to any person, with intent in any such case to commit murder, shall be liable to imprisonment for 25 years. Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 11 5.4 Mitigating factors 5.4.1 Lack of hostility does not negate mens rea Boughey (1986) Doctor strangled his wife for sexual arousal No hostility Held: hostility is not necessary to establish mens-rea 5.4.2 Consent to assault Consent (express or implied (Collins v Wilcock (1984))) nullifies assault (Clarence (1888)); commonplace actions (pat on the back, etc) have implied consent (Boughey (1986)). V cannot consent to ABH or higher (Brown (1994)); unless in exception (boxing, surgery, “manly pastimes”). With regards to sport, the harm must be within the recognized reasonable rules of the game, and in a sporting spirit (i.e. not in anger) (Pallante v Stadiums) 5.4.3 Physical assault during consensual sex Protected by Human Rights (Sexual Conduct) Act 1994 (s4(1)). Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 12 6 Sexual Assault This is an extremely codified section of law; Part 3, Division 10. 6.1 Elements Sexual Assault Actus Reus Sexual intercourse (s61H) Without consent (s61HA) Mens Rea Intent to have non consensual sexual intercourse; OR Reckless non-consensual intercourse No reasonable grounds for believing the other person consented to sexual intercourse Temporal Coincidence 6.2 Offenses S61I – Sexual assault S61J – Aggravated sexual assault o Sources of aggravation (2) ABH (a) Weapon (b) Company (c) V is under 16 (d) V is under D’s authority (e) V is physically disabled (f) V is cognitively disabled (g) (defined in s61H(1A)) D is in the commission of a serious indictable offense, or breaks into the house (h) V is falsely imprisoned (i) 61JA – Aggravated sexual assault in company o In company (1)b) o AND o ABH, weapon or falsely imprisons (c) 6.3 Definition of “sexual intercourse” (s61H) Penetration of the vagina or anus by any part of the body or manipulated object (ss(1)a)). o Even for gender reassigned o Only the slightest penetration necessary (Papadimitropoulos (1957) Fellatio (ss(1)b)) Cunnilingus (ss(1)c)) Is a continuing act (ss(1)d)) Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 13 6.4 Consent (s61HA) Definition: A person "consents" to sexual intercourse if the person freely and voluntarily agrees to the sexual intercourse (ss(2)). No consent if (ss(3)). Knowledge (a) Recklessness (b) No reasonable grounds (c) o Court can use attempts to ascertain consent to disprove recklessness (d), no selfinduced intoxication is relevant to disprove recklessness (e). Consent is negated if (ss(4)): Person does not have the capacity to consent (a), s61H(1A) Unconscious/asleep (b) Consent is by force/terror (c) Consent is by person falsely imprisoned (d) Mistaken belief of (5) o identity (a) o marriage (b) o false belief that sex is for medicine/hygene (c) o This must be of the act itself and not the quality of the act (Mobilio). Consent negation may be found by (6): V is grossly intoxicated (a) V is coerced/intimidated (b) D uses authority wrongly (c) Lack of a struggle does not imply consent (7). The above list is not exhaustive (8) 6.4.1 Age of Consent If under 10, incapable of consent (s66A) If under 16, rebuttable presumption (s66C) (D can prove on balance of probabilities 6.4.2 Marriage does not imply consent s61T Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 14 6.5 Mens Rea 6.5.1 Intention If D intends to have sexual intercourse with V, knowing that V does not consent (s61HA(3)(a)). If D honestly believes that V was consenting then D will lack the MR, even if this belief is unreasonable (DPP v Morgan). 6.5.2 Recklessness If D is reckless as to whether V consents to sexual intercourse (s61HA(3)(b)). o The possibility of non-consent (Saragozza (1984)). D can be guilty for either reckless advertence or inadvertence (Kitchener). 6.5.3 No reasonable grounds for belief in consent D has no reasonable grounds for believing that V consents to sexual intercourse (s61HA(3)(c)), then mens rea is satisfied Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 15 7 Attempt Liability as per offense (s344A) 7.1 Actus reaus Beyond preparation (Collingridge) Asserted via: o Proximity (acts remotely connected =/ attempt, they have to be immediately connected (Eagleton) o Last act before completion (Eagleton) o Would offence have been committed if it had not been interrupted (Haughton v Smith) o Attempt only substantiated if there is unequivocal indication of intent to commit an offence (Barker) Voluntary stopping is no defense (O’Connor v Killian) Impossibility of completing offense does is not defense (Britten v Alpogut) 7.2 Mens Rea Had intention (recklessness insufficient (Giorgianni)) to commit specific harm associated w offense (Knight). Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 16 8 Joint Criminal Enterprises 8.1 Doctrine of common purpose Extends liability for incidental crimes (McAuliff) if D can foresee act as possible incident of the original crime (Johns) To withdraw: must be timely and clearly communication (Rook) and must nullify participation (White v Ridley) Principle need not be charged/found guilty. Innocent agents are not guilty (Cogan v Leak; Hewitt) 8.2 Offenses Actus reus P1, Present @ Actus P2, not Mens rea P1, as crime P2, knowledge of crime 8.2.1 AR Principle in the 2nd degree (s345) charged as P1 Aids = natural meaning – give support or assist (Beck). Abetting = incite, instigate, encourage (Giorgi). Counselling = encouragement or advice prior to commission of crime. Procure = causes or brings about offence (AG’s Reference (No 1 of 1975)). o Only procuring requires causal link between D’s conduct and commission of offence (AG’s Reference (No 1 of 1975). MR Knowledge of the essential facts of the crime(Giorgianni); and o Wilful blindness = knowledge BUT negligence or recklessness = insufficient. o Need not contemplate precise crime but should be same type or kind (Bainbridge). With this knowledge D intentionally aided, abetted, counselled or procured the acts of P (Giorgianni). 8.2.2 Accessory before the fact (s346) 8.2.3 Accessory after the fact (s457) 8.2.4 Aidors and Abbettors charged as principles (s351B) 8.2.5 Recruiting persons to commit a crim (s351A) (3) "recruit" means counsel, procure, solicit, incite or induce. Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 17 9 Defences 9.1 Automatism Prosecution may presume voluntariness (Falconer). D must satisfy evidential burden by raising the possibility that D’s actions were involuntary. Then prosecution must prove beyond reasonable doubt that acts were voluntary. If D successful = complete acquittal. Distinguishing between sane/insane automatism (Falconer): o Recurrence test: If a mental condition is prone to recur, it should be considered a disease of the mind (Bratty v AG Northern Ireland). o Internal/external test: If the mental state is internal (Hennessy) to D, as opposed to arising from an external cause (Quick), then it should be defined as a disease of the mind (Falconer). o Unsound/sound mind test: A disease of the mind is considered to be evidenced by the reaction of an unsound mind to its own delusions or external stimuli (Radford). 9.2 Insanity D bears burden of proving insanity on BOP (Ayoub) and results in a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity detained in custody for indefinite period. M’Naghten’s Rules: At time of committing act D was labouring under a defect of reason, owing to a disease of the mind, so as: 1. Not to know the nature and quality of their act; or 2. If D did know, then D did not know that what they were doing was wrong. Disease of the mind (Porter) can include: o Arteriosclerosis (hardening of arteries affecting the body) (Kemp). o Hyperglycaemia (Hennessy). o Malfunctioning of the mind due to insulin (Quick). o Sleepwalking (Burgess). o Epilepsy (Sullivan). ‘Nature and quality of the act’ has been defined as referring to the physical nature and consequences of the act, rather than to its moral aspects (Sodeman). ‘Wrong’ = wrong according to the principles of ordinary people (Porter); not wrong in the sense of being contrary to the law (Stapleton). The defence may exclude psychopaths (Willgoss) and someone suffering from irresistible impulse (AG v Brown). Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 18 INSANITY AUTOMATISM (relieves A of responsibility for crime) (negates actus reus element of voluntariness) Availability Any charge Any charge Verdict Complete defence Sane automatism complete defence (acquittal). (finding not guilty by reason of insanity). Insane automatism (finding not guilty by reason of insanity). Punishment Acquittee detained for indefinite period. Acquittee detained for indefinite period (insane). Legal distinction Narrow test for mental disorder. Defence confined to sane automatism (otherwise may be subsumed by insanity). Burden of Proof Defence must prove on balance of probabilities. Ie. D is more likely than not to be insane. If D discharges burden P must disprove BRD. Defence has evidentiary burden (sane automatism) ie put forward sufficient evidence as to reasonable possibility of automatism. If D satisfies evidentiary burden P must disprove BRD. Insane automatism same as insanity. Relevance of Intoxication Temporary intoxication does not amount to a disease of the mind. If intoxicant acts as trigger to underlying disease of mind then may satisfy the rules of the defence. Self-induced intoxication cannot be taken into account to determine whether conduct was voluntary. Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 19 9.3 Intoxication Not a defence in itself but may negate elements of a crime (involuntariness or insanity). In NSW D can incur liability while lacking vital elements of the offence, due to the culpability of becoming intoxicated (Majewski). The reasonable person is to be considered sober (s428F). Self induced intoxication (s428A) UNLESS it was involuntary: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Fraud Sudden Emergency Accident Reasonable Mistake Duress or force Where prescription/non-prescription drug taken in accordance with instructions Can intoxication be used to negative the AR (i.e. render the act involuntary)? Self Induced Intoxication = NO! (s428G(1)) Involuntary Intoxication = YES! (s428G(2)) Can intoxication be used to negative the MR? Specific intent (s428B) = if MR requires intention (larceny, s33, joint crim enterprise). Basic intent = negligence/recklessness (s61, s59, s35). YES! (428C(1)) NO! = self-induced intoxication (s428D(1)) BUT not where D became intoxicated for ‘dutch courage’ (s428C(2); AG v Gallagher) YES! = involuntary intoxication (s428D(2); Kingston) Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 20 9.4 Self-Defence D must satisfy the evidentiary burden to raise the defence of self-defence, and if satisfied, the prosecution must then negate the defence beyond a reasonable doubt (s 419). A person may be justified in using some level of self-defence (s418(1)) for: Defence of self (s418(2)(a)) and own liberty (s418(2)(b); Other persons (s418(2)(a)) and their liberty (s418(2)(b); Defence of property (s418(2)(c)); Effecting lawful arrest (s418(2)(d)). Must satisfy both tests (Katarzynski): 1. SUBJECTIVE test: Is there a reasonable possibility that the accused believed his conduct was necessary within the circumstances? 2. OBJECTIVE test: Is there a reasonable possibility that what the accused did in his/her selfdefence was a reasonable response as he/she perceived them? a. Reasonable person is sober – i.e. self-induced intoxication NOT taken into account (s428F). Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 21 9.5 Duress D must satisfy the evidentiary burden but, once this is satisfied, the prosecution must negative the defence beyond reasonable doubt. Full acquittal if D succeeds. D not liable for a crime where it was committed due to a threat of physical harm to D (or another person) if D refused to comply (Hurley). Establishing duress (Hurley): 1. Serious threat if act not done – recognised threats include: Death and GBH to a person (Hurley); A lawful nature (child/insanity); Imprisonment (Lawrence); Torture causing intense pain but without residual injury (Goddard v Osborne); Harm to a third party (Abusafiah) 2. An average person of ordinary firmness of mind, of like age and sex, in like circumstances would have yielded to the threat – OBJECTIVE test (Lawrence). BWS can be considered (Runjanjic). 3. The threat was present and imminent. Threat may be present and continuing even if threatener has no direct physical control over D at the time D commits the crime (Hudson). 4. Accused reasonably believed that would be carried out. 5. The threat actually induced the crime. Threat overbore D’s will D incapable of acting independently (AG v Whelan). 6. Crime was not murder. 7. D did not, by their own fault, expose themselves to the threat. 8. No reasonable way of avoiding the threat – OBJECTIVE test (Lawrence). Failure to seek police protection, due to the reasonable belief that such aid would be ineffectual will not necessarily exclude the defence (Brown). Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 22 9.6 Necessity D should not be liable for criminal acts where D was compelled due to sudden or extraordinary emergency (White). Establishing necessity (Loughnan): Act must have been done to avoid consequences that would have inflicted irreparable harm on V or those they were required to protect. Threat must place immense pressure due to imminence or gravity of threat. D must honestly believe on reasonable grounds that there is a threat of imminent peril o Ordinary person must have been capable of wielding in the way that D did. Acts done to avoid peril must not be out of proportion to the peril avoided o Must be reasonable and necessary; no other alternative. Abortions are unlawful unless they are necessary (s82) – court has a relaxed view on what is necessary (Davidson). Johanan Ottensooser 70218 – Criminal Law: Autumn 2010 23