Air Pollutant Watch List Proposed Change, Removal of Texas City

advertisement

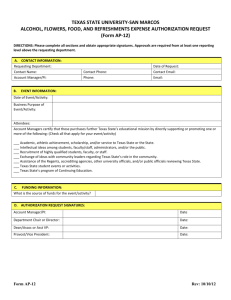

Air Pollutant Watch List Proposed Change Removal of Texas City, Benzene Texas Commission on Environmental Quality Air Permits Division March 11, 2013 Summary The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) established the Air Pollutant Watch List (APWL) to address areas of the state where air toxics were monitored at levels of potential concern, and the TCEQ uses the APWL to reduce air toxic levels by properly focusing limited state resources on areas with the greatest need. The TCEQ added a portion of Texas City to the APWL to address persistent, elevated ambient concentrations of air toxics, including the air toxic benzene. Since Texas City’s inclusion on the APWL, the TCEQ has increased monitoring, investigations, enforcement, and air permitting efforts for the companies located in the APWL area. The primary benzene contributors in the Texas City APWL area have implemented significant equipment improvements. Companies have implemented voluntary measures to reduce benzene and have also agreed to make improvements through the TCEQ and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) enforcement process. Certain companies continue to use monitoring data to identify elevated concentrations and mitigate emissions. The TCEQ’s Toxicology Division establishes air monitoring comparison values (AMCVs) to evaluate ambient air toxic data. No adverse health effects would be expected if annual average benzene concentrations remain below 1.4 parts per billion by volume (ppbv). Stationary monitoring data show that annual average benzene concentrations have remained below 1.4 ppbv at each monitoring location in Texas City for two consecutive years. For example, the 2010 and 2011 annual average benzene concentrations were 0.5 ppbv at TCEQ’s Texas City Ball Park Monitor; 0.4 ppbv and 0.3 ppbv (respectively) at BP’s 31st Street Monitor; 0.6 ppbv and 0.5 ppbv at BP’s Logan Street Monitor; and 0.9 ppbv and 0.8 ppbv at Marathon’s 11th Street Monitor. The TCEQ determined that monitored concentrations can reasonably be expected to be maintained below levels of potential concern and is proposing to remove benzene in Texas City from the APWL. Texas City would remain on the APWL for the air toxic propionaldehyde. 2 Area and Pollutant of Concern The TCEQ established the APWL to address areas of the state where air toxics were monitored at levels of potential concern. Figure 1, Texas City APWL Area 1202, illustrates the portion of Texas City that the TCEQ has included on the APWL. The TCEQ added this area to the APWL to address persistent, elevated ambient concentrations of air toxics, including the air toxic benzene. Figure 1: Texas City APWL Area 1202 Benzene, a widely used industrial chemical, is a clear liquid that readily evaporates into the air. Benzene occurs naturally in crude oil, and therefore refined products like gasoline contain benzene. Benzene is also used to make glues, lubricants, and certain prescription medications. Several agencies, including the TCEQ, the EPA, the National Toxicology Program, and the International Agency for Research on Cancer, have 3 designated benzene as a human carcinogen. The TCEQ has developed a Development Support Document, which provides additional detailed information on the potential toxicological effects of benzene. The bold yellow line in Figure 1 shows the boundary of the Texas City APWL area, and the thinner green lines represent streets. Some of the industrial equipment owned and operated by the companies in the Texas City APWL area, like larger storage tanks, can be seen in Figure 1. Designated Land Use and Proximity to Residential Areas and High-Traffic Roadways The Texas City APWL area boundary encompasses the area south of Texas Avenue/State Highway (SH) 348/Farm-to-Market Road (FM) 1765, east of Highway 146, and west of Galveston Bay. The majority of this land area is industrial; however, there are some residences located within the APWL boundary designation for the area. Some of these homes are also located in close proximity to industrial equipment. Most of the population density in the area is located north of SH 348 (approximately a quarter-mile north of the industrial complexes) and west of Hwy 146 (where, in some places, homes are within one-tenth of a mile of industrial equipment). The streets that make up the APWL boundary are high-traffic roadways. Highway 197 is also a high traffic roadway, running between some of the industrial complexes in the APWL area. In addition, the area around Swan Lake is located within the APWL boundary and is designated as a waterfront conservation and recreational area. 4 Companies Located in the Texas City APWL Area Table 1, Companies in the Texas City APWL Area, lists the 19 industrial complexes located within the APWL boundary. Table 1: Companies in the Texas City APWL Area Company Name Regulated Entity (RN) Number BP Products North America (BP) RN102535077 Marathon Petroleum – Texas City Refinery (Marathon) RN100210608 Valero Refining Texas City Refinery (Valero) RN100238385 Praxair Texas City (Praxair) RN100220599 Praxair Texas City Hydrogen Complex (Praxair HC) RN104095435 Union Carbide Texas City (Union Carbide) RN100219351 BP Texas City Chemical Plant B (BP Chem) RN102536307 Eastman Chemical Texas City (Eastman) RN100212620 INEOS Texas City Chemical Plant (INEOS) RN104579487 Oiltanking Texas City Terminal (Oiltanking) RN100217231 NuStar Texas City Terminal (NuStar) RN100218767 Texas City Cogeneration (TX City Cogen) RN100224245 South Houston Green Power (SH Green Power) RN103934493 Enterprise Crude Pipeline, Seaway Texas City Station (Enterprise) RN102560182 Shell BP Texas City Compression Dehydration Facility (Shell) RN105644223 Marathon Pipe Line Texas City Pump Station (Marathon Pipe Line) RN104574918 Gulf Coast Waste Disposal Authority (GCWDA) RN100212463 Bollinger Texas City (Bollinger) RN100218627 Oxbow Marine Terminal Texas City (Oxbow) RN102707049 As Table 1 illustrates, Texas City APWL area 1202 is highly industrialized. The APWL area contains three petroleum refineries (BP, Marathon, and Valero), six chemical plants (two Praxair sites, Union Carbide, BP Chem, Eastman, and INEOS), three petroleum and chemical terminals (Oiltanking, NuStar, and Enterprise), two power generation plants (TX City Cogen and SH Green Power), two oil and gas support facilities (Shell and Marathon Pipe Line), a wastewater treatment facility (GCWDA), a barge manufacturing and repair facility (Bollinger), and a petroleum coke and coal 5 material handling facility (Oxbow). Figure 2, Texas City APWL Companies, shows the relative locations of the industrial complexes within the APWL boundary. Figure 2: Texas City APWL Companies Emissions Inventory Owners or operators of certain stationary sources are required by Title 30 Texas Administrative Code §101.10, Emissions Inventory Requirements, to submit an annual emissions inventory to the TCEQ. A company is required to report all of its actual air emissions each year, including all authorized and unauthorized emissions. Unauthorized emissions may include those emissions released as a result of emissions events or unauthorized maintenance, startup, and shutdown (MSS) activities. Companies located in APWL areas are subject to this requirement. Of the 19 companies located in the APWL area, 12 of them have reported benzene emissions in their emissions inventories, as the following table illustrates. 6 Table 2: Tons of Benzene Emissions Reported by Companies in the APWL Area* Company 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 BP 85.31 32.22 33.69 54.88 47.79 64.05 61.83 75.4 66.33 29.96 45.63 Marathon 12.84 17.06 16.32 16.28 15.61 14.52 14.31 15.2 14.58 10.88 8.55 Valero 9.84 8.56 8.37 40.41 5.92 3.35 4.25 4.59 7.85 4.44 5.04 Eastman 32.78 9.33 11.53 12.72 17.87 15.47 16.05 17.32 5.93 0 0 Union Carbide 17.15 10.64 17.3 26.17 1.23 0.95 0.05 0.05 0.02 0.03 0.02 Oiltanking 0.31 0.19 0.33 0.19 0.04 1.61 6.2 8.17 7.1 5.67 2.15 BP Chem 3.61 3.53 3.76 3.77 12.27 1.06 0.23 0.62 0.17 5.56 3.2 GCWDA 0.41 0.77 0.1 0.21 0.21 0 0 0 0 0 0 INEOS 0 0 0 0 0 6.33 4.85 15.34 3.51 1.84 1.87 NuStar 0 0.02 0.09 0.11 0.59 0.53 1.97 1.98 3.57 2.48 0 Enterprise 0.29 0.42 7.02 9.17 8.1 9.74 8.28 2.26 0.35 0.32 0.18 TX City Cogen 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.11 0.11 0.1 Total 162.54 82.74 98.51 163.91 109.63 117.61 118.02 140.93 109.52 61.29 66.74 *Includes emissions resulting from emissions events and unplanned MSS activities. Monitoring of Benzene in Texas City The TCEQ has historically conducted mobile monitoring projects and has also used stationary monitoring data to evaluate ambient benzene concentrations in Texas City. The TCEQ began evaluating ambient benzene monitoring data from the stationary Texas City Nessler Pool Monitor in 1995. Since 2001, the TCEQ has conducted mobile monitoring projects in Texas City and has measured elevated benzene levels. The Galveston City-County Health Department previously operated the stationary Nessler Pool Monitor, which was located at 17th and 5th Avenue North. The monitoring site operated from January 1, 1979, to July 30, 2007. On October 20, 1997, the TCEQ activated the Texas City Ball Park Monitor (AQS Number 481670005), a stationary monitor located at 2516 ½ Texas Avenue. The TCEQ continues to collect ambient benzene data from this site. The Texas City Ball Park Monitor is a 24-hour canister sampler, as was the Nessler Pool Monitor. These canisters collect a 24-hour sample every sixth day. In addition to the active TCEQ stationary monitoring site, individual Texas City companies sponsor four monitoring sites. Two companies installed the monitors 7 pursuant to individual enforcement agreements with the TCEQ and/or the EPA and U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). The TCEQ refers to these monitoring locations as “industry-sponsored” monitoring sites. These four monitoring sites contain automated gas chromatograph monitors (auto GCs), which provide the ambient concentration of benzene and other chemicals on an hourly basis. Table 3, Industry-Sponsored Stationary Monitors, lists the four industry-sponsored monitoring sites. Table 3: Industry-Sponsored Stationary Monitors Monitoring Site Name AQS Number Location Owner Texas City BP Logan Street Monitor 481670621 303 Logan Street BP Texas City BP On-Site Monitor 481670616 BP property near Highway 197 BP Texas City BP 31st Street Monitor 481670615 BP property between Texas Avenue and 5th Avenue BP Texas City 11th Street Monitor 481670683 502 10th Street South Marathon The Texas City/La Marque Community Air Monitoring Network also operates four stationary monitors in the Texas City area. This network is supported by a financial agreement between participating companies and an independent operator/contractor who conducts and validates the monitoring data from the Texas City/La Marque Community Air Monitoring Network. This data is then presented to the TCEQ on a periodic basis. Unlike the Texas City Ball Park Monitor and the industry-sponsored monitors, the TCEQ does not prescribe data quality standards for the community air monitoring network. The four Texas City/La Marque Community Air Monitoring Network monitoring sites are: (1) Avenue A; (2) 2nd Avenue; (3) 34th Street; and (4) the North Site. The 34th Street site contains an auto GC, the Avenue A and North Site1 Monitors contain 24-hour canister samplers, and the 2nd Avenue site contains an auto GC and a 24-hour canister sampler. Use of the 34th Street Monitor was critical in the TCEQ’s evaluation, remediation, and delisting of APWL 1203, which was a separate benzene APWL area near the Black Marlin Pipeline Company Texas City (Williams Field Services Group LLC; RN100906155), in 2004. Figure 3, Texas City Stationary Monitoring Sites, illustrates the locations of the monitors discussed in this section in relation to the Texas City APWL 1202 area (bottom right corner) and the historical APWL 1203 area above left (surrounding the 34th Street Monitor). All canister samplers discussed in this document collect a 24-hour sample every six days, with the exception of the North Site and 2nd Avenue canister samplers, in which a 24-hour sample is collected every 12 days. 1 8 Figure 3: Texas City Stationary Monitoring Sites Evaluating Air Monitoring Data The TCEQ evaluates concentrations of air toxics, like benzene, through the use of its AMCVs. AMCVs are screening values that are chemical-specific air concentrations established by the TCEQ’s Toxicology Division, and are designed to protect human health and welfare. The Toxicology Division establishes both short-term AMCVs and long-term AMCVs. Short-term AMCVs are based on data concerning acute health effects, the potential for odors, and effects on vegetation. Long-term AMCVs are based on data concerning chronic health and vegetation effects. Short- and long-term, healthbased AMCVs are set below levels at which health effects would occur. Short-term AMCVs are based on a one-hour exposure scenario, whereas long-term AMCVs are based on lifetime exposures, approximately 70 years. The Toxicology Division uses its scientifically-rigorous effects screening level guidelines to establish these AMCVs, in 9 which proposed AMCVs are scrutinized through a scientific peer review and public comment process. More details on AMCVs can be found on the TCEQ’s Web site. The short-term, health-based AMCV for benzene is 180 ppbv. The long-term, healthbased AMCV for benzene is 1.4 ppbv as a lifetime average exposure concentration, although it is compared to the calendar year annual average to determine if concentrations should be reduced. Canister samplers (like the Nessler Pool and Texas City Ball Park Monitors discussed previously) collect data every six days for a 24-hour period. Canister data are then averaged and compared to long-term AMCVs. Auto GCs (like the industry-sponsored monitors) collect data every hour. Auto GC data are, therefore, appropriate for comparison to short-term AMVCs. Auto GC data are also averaged annually for comparison to long-term AMCVs. Mobile monitoring samples provide data over a short duration (samples are usually instantaneous or are taken over a period of time up to three hours) and must be compared to short-term AMCVs. Reasons for Texas City’s Inclusion on the APWL The TCEQ added Texas City (APWL 1202) to the APWL in 2001 to address elevated concentrations of the air toxic propionaldehyde—an odorous compound used in the manufacture of plastics, in the synthesis of rubber chemicals, and as a disinfectant and preservative. The TCEQ then added benzene to the Texas City APWL area in 2003 because, for multiple years, the annual average benzene concentration at the Texas City Ball Park Monitor had exceeded the long-term, health-based AMCV of 1.0 ppbv.2 In addition, the TCEQ measured five exceedances of the 180 ppbv short-term, health-based AMCV during a 2001 mobile monitoring project in Texas City. Benzene Data Collected After Area’s Inclusion on the APWL After Texas City was added to the APWL, annual average benzene concentrations have exceeded the long-term AMCV of 1.0 ppbv at additional locations other than the Texas City Ball Park Monitor. These exceedances have been monitored at the 34th Street, 31st Street, and 11th Street Monitors. In 2007, the TCEQ conducted a thorough scientific evaluation of the toxicity of benzene and derived a new long-term, health-based AMCV of 1.4 ppbv using the most up-to-date and scientifically defensible methods. After the TCEQ established the current long-term AMCV of 1.4 ppbv in 2007, annual average benzene concentrations continued to exceed levels of concern at the 11th Street Monitor. In addition, although the data are not representative of public exposure and therefore not used to determine the potential for health effects in the general public, annual average benzene concentrations have exceeded the 1.4 ppbv long-term AMCV at the BP On-Site and Marathon On-Site Monitors.3 The annual average benzene concentration at the Texas City Ball Park Monitor was 1.2 ppbv in 1998, 1.1 ppbv in 1999, 1.5 ppbv in 2000, 1.3 ppbv in 2002, and 1.2 ppbv in 2003. 3 Ambient concentrations are evaluated in conjunction with wind directional data in order to help identify sources of air toxics that potentially contribute to elevated concentrations. BP operates an on-site monitor, and Marathon previously operated an on-site monitor. These on-site monitors provide data that, from the predominant wind direction, is upwind of the companies’ benzene sources (and nearby houses). Having an upwind and a downwind monitor is extremely useful in better understanding an 2 10 In addition to data collected from stationary monitors in the surrounding area, a mobile monitoring project in 2008 measured three exceedances of the short-term, health-based AMCV. Health Effects Reviews of Ambient Monitoring Data and Previous Source Determinations The TCEQ has conducted annual health effects evaluations regarding the benzene monitoring data in Texas City for many years. In its health effects review memorandums, the TCEQ’s Toxicology Division has encouraged emission reductions in Texas City because annual average benzene concentrations have exceeded long-term, health-based AMCVs at the Texas City Ball Park, 31st Street, and 11th Street Monitors. The memorandums also describe the Toxicology Division’s source evaluations using the Texas City Ball Park, 31st Street, and 11th Street monitoring data as well as data from BP and Marathon’s on-site monitors. The Toxicology Division determined that auto GC data at the 31st Street Monitor indicated that higher benzene concentrations were associated with winds blowing from the direction of BP. Similarly, the Toxicology Division determined that higher benzene concentrations at the 11th Street Monitor were most frequently associated with winds blowing from the direction of Marathon. TCEQ Actions to Reduce Benzene Emissions The purpose of the APWL is to reduce ambient air toxic concentrations below levels of potential concern. The TCEQ uses the APWL to properly focus limited state resources on areas with the greatest need. The TCEQ also uses the APWL to heighten awareness of elevated concentrations and to engage the companies in APWL areas to encourage efforts to reduce emissions. In Texas City, the TCEQ increased its monitoring efforts with the deployment of its mobile monitoring team. Additionally, as discussed previously in this document, two of the larger benzene contributors in the area operate stationary monitors. The TCEQ also focused its compliance and enforcement resources to ensure that companies located in the APWL area are operating in compliance. Initially, the TCEQ used monitoring data in conjunction with emissions events and compliance reports as well as information found during routine records reviews and inspections to identify potential violations and non-compliant emissions. In addition to the routinely scheduled, comprehensive compliance investigations for all major sources in the region, investigators have conducted surveillance (during business hours and also after hours) individual company’s contribution of an air toxic to the ambient air, and is also helpful in better pinpointing sources of emissions. It is important to note that BP’s on-site monitor and, formerly, Marathon’s on-site monitor do not provide data that is representative of potential exposure to the community due to their locations. These monitors were located on industrial property, away from residences and other sensitive receptors. Where the data from the on-site monitors is used to better pinpoint benzene sources, the Texas City Ball Park, Logan Street, 31 st Street, and 11th Street Monitors are downwind monitors that are located closer to residences and provide data that is, hence, more representative of community exposure. As discussed later in this document, data from the Texas City Ball Park, Logan Street, 31st Street, and 11th Street Monitors demonstrate that the annual average benzene concentrations have been maintained below the AMCV, a level of potential health concern. 11 using the GasFind Infra-Red camera to detect equipment leaks in an effort to identify possible non-compliant volatile organic compound emissions (which include benzene). Investigators conducted on-site investigations regarding any issues identified during surveillance activities and also conducted focused benzene investigations at APWL companies to look for unreported and under-reported benzene emissions. Additionally, TCEQ’s Region 12 Office undertook an initiative regarding the degassing or cleaning of stationary, marine, and transport vessels in 2010 in response to citizen complaints. The increased efforts by TCEQ’s Region 12 staff have resulted in the issuance of multiple Notices of Violation (NOVs) to several of the companies in the Texas City APWL area. The commission has thusly been able to enter into Agreed Orders with several of the companies to resolve its concerns. Through the enforcement process, several companies in Texas City have agreed to conduct significant activities to monitor and reduce benzene emissions in Texas City. In addition, the EPA’s Petroleum Refinery Initiative resulted in emission reductions from refineries across the country. All three of the refineries located in Texas City entered into settlement negotiations with the EPA in response to its Petroleum Refinery Initiative and agreed to implement improvements to reduce benzene emissions. The summary below describes some of the positive changes that were effectuated through the TCEQ Agreed Order and/or EPA Consent Decree process. BP has entered into multiple Agreed Orders with the TCEQ since the mid-90s regarding alleged violations at its petroleum refinery located at 2401 5th Avenue South. Two of the relevant Agreed Orders stipulating improvements are Agreed Order 2001-0329-AIR-E and Agreed Order 2005-0224-AIR-E. BP also entered into a Consent Decree (Civil No. 2:96 CV 095 RL) with the EPA in 2001 relating to alleged violations at multiple locations around the country, including the Texas City refinery. Some significant improvements required by Agreed Order/Consent Decree include: Requirement to cease discharging process wastewater into the oil-water separator and storm water basin at Plant A along Highway 197; Requirements for Benzene Waste National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants Program enhancements, including a waste stream audit and installation of dual, sequential carbon canisters; Requirements for Leak Detection and Repair enhancements and sustainable skip period monitoring program; Preparation of a comprehensive report identifying each benzene emission point and fugitive source, its authorization and other requirements regulating benzene, and benzene emissions data; Development of a monitoring plan including the installation of two auto GC monitors, one near the refinery’s northwest corner and one near the southeast corner; Commencement of the Benzene Tank Upgrade project to install controls on floating roof tanks used for storing benzene or benzene containing materials; and Minimization of emissions from flares and other combustion devices, including the operation of flare gas recovery systems. 12 In response to BP’s March 2005 explosion, the Texas Attorney General’s Office issued a Temporary Injunction (No. D-1-GV-09-00921), requiring BP to operate the Logan Street Monitor. The Agreed Final Judgment, filed in Travis County District Court in December 2011, stipulated a large penalty and no additional technical requirements, although BP continues to operate the Logan Street Monitor. Additionally, the EPA conducted a series of inspections after the explosion to determine BP’s compliance with the terms of the 2001 Consent Decree, and BP agreed to implement additional measures to address benzene. Marathon, who operates a petroleum refinery at 1320 Loop 197 South, through the enforcement process, has also agreed to conduct ambient benzene monitoring. Agreed Order 2001-0575-AIR-E required Marathon to submit a benzene monitoring plan to measure concentrations of benzene within the surrounding communities, using an auto GC monitor for a 12-month period. Marathon conducted this monitoring from October 2004 to October 2005. Marathon continued to collect monitoring data at the site from January 2006 to January 2007 under a benzene emission investigation plan with the TCEQ and the EPA. Marathon, through a Consent Decree with the EPA and the DOJ (Civil Action No. 4:01-CV-40119-PVG, which also stipulated decreases in emissions from leak detection and repair of fugitive components and the control of benzene emissions from wastewater treatment and conveyance systems), again began monitoring benzene in April 2007 and continued monitoring until December 2009. Agreed Order 20081709-AIR-E required the continuation of monitoring through December 2010, including the implementation of an Environmental Monitoring Response System, which notifies Marathon staff that an internal investigation is warranted when ambient concentrations exceed a specified trigger level. More recently, Marathon has entered into an agreed order settlement with the EPA (EPA Docket No. CAA-06-2011-3318), specifying that Marathon continue monitoring from July 1, 2011 to July 1, 2014. Marathon, in response to an EPA Consent Decree, optimized the operation of its flares. Valero entered into multiple Agreed Orders for its petroleum refinery located at 1301 Loop 197 South. Some of the Agreed Orders addressed violations relating to benzene and/or volatile organic compounds. Valero agreed to implement corrective measures. Valero also installed a flare gas recovery system in April 2009 (Agreed Order 20100390-AIR-E). Valero also committed to implement enhanced procedures to reduce or eliminate fugitive benzene waste emissions through a consent decree with the EPA (Civil Action No. SA05CA0569RF). INEOS, who operates a chemical plant at 2800 Farm-to-Market Road 519, entered into Agreed Order 2010-0261-AIR-E, relating to an unauthorized release of benzene from the cooling tower in the ethylbenzene unit when multiple tubes in a heat exchanger failed due to corrosion. The company implemented corrective measures including the complete retubing of the heat exchanger with upgraded metallurgy, updating the lab system to flag high sample results, and training personnel to avoid future violations. In addition to increased monitoring, investigations, and enforcement, the TCEQ has focused its air permitting efforts for companies located in APWL areas, including Texas City. The TCEQ has scrutinized air permit applications for those companies in the Texas City APWL area requesting an increase in benzene. In addition, the TCEQ is in the process of evaluating emissions from routine MSS that have been historically 13 unauthorized for sites located throughout the state. A permit review of MSS activities includes an evaluation of best available control technology and a health impacts review, and MSS permitting often requires controls and/or operational changes for activities that have been previously uncontrolled (and, in some cases, controls are required for equipment whose emissions were previously vented to the atmosphere). The TCEQ has specifically evaluated and permitted MSS activities from two of the three petroleum refineries in Texas City—BP and Valero. BP is now required to control vapors from depressurizing, draining, and degassing equipment; implement additional controls for degassing floating roof and fixed roof tanks; and painting white the tanks that store liquid temporarily during the duration of MSS for other equipment. Valero’s permit now also specifies additional control requirements for tank purging; eliminates convenience tank landings; requires controls for vacuum truck vapors; and requires certain tanks to be painted white. The authorization of MSS activities for these two refineries requires additional controls, helping to further ensure that activities at the refineries are properly controlled and are protective of human health and welfare. Additional Pollution Prevention Efforts In addition to the improvements described in the previous section that were effectuated through the enforcement process, some companies in the Texas City AWL area have implemented additional, voluntary measures to reduce benzene emissions. Marathon implemented operational changes to significantly reduce emissions associated with losses from the tanks that have historically stored high benzene-content liquid near sensitive receptors, including reducing throughput and the number of turnovers from the tanks. Marathon also installed a new solvent sewer in its aromatic recovery unit, installed a thermal oxidizer for its wastewater treatment plant, and has changed the method of operation of its benzene extraction unit to reduce emissions. In addition, Marathon has implemented internal notification procedures to better identify and respond to elevated benzene concentrations observed at the 11th Street auto GC. As discussed previously, Marathon is required to conduct monitoring. The company is also required to take action when ambient hourly benzene concentrations are monitored at a certain trigger level; however, Marathon has implemented much lower trigger levels to investigate lower concentrations of benzene. Additionally, Marathon inspects sewers, tanks, and fugitive components with an FLIR camera to check for vapor tightness. BP has also implemented procedures to respond to elevated hourly concentrations at its auto GCs and also uses an infrared camera to check for leaks. In addition, Eastman permanently shut down its ethylbenzene and styrene units in 2008, reporting no benzene emissions in its 2009 or 2010 emissions inventories. Monitored Decline in Ambient Benzene Concentrations TCEQ’s Texas City Ball Park Monitor The annual average benzene concentration at the Texas City Ball Park Monitor was at its highest value in 2000, in which the annual average concentration was 1.5 ppbv. This is the only year in which the annual average benzene concentration exceeded the current 14 long-term AMCV of 1.4 ppbv. In 2001, the monitor did not collect enough valid data to be considered complete for the year (the TCEQ established a 75 percent completeness objective for data analyzed at the TCEQ laboratory), but the average of the data collected was 1.0 ppbv. In 2002, the annual average benzene concentration was 1.3 ppbv, and the annual average concentrations have declined significantly since that time. The annual average concentration was 1.2 ppbv in 2003, 1.0 ppbv in 2004, 1.1 ppbv in 2005, 0.8 ppbv in 2006, 0.6 ppbv in 2007, 0.7 ppbv in 2008, 0.6 ppbv in 2009, 0.5 ppbv in 2010, and 0.5 ppbv in 2011. All of these concentrations are below the long-term AMCV of 1.4 ppbv and show a downward trend. Furthermore, the TCEQ determined that the rolling 12-month average as of March 28, 2012, was 0.5 ppbv at the Texas City Ball Park Monitor, also indicating sustained improvement. Industry-sponsored Monitors The annual average benzene concentrations at the industry-sponsored monitors have also declined significantly. The TCEQ specifically evaluated the potential for health effects from BP’s 31st Street and Logan Street Monitors and Marathon’s 11th Street Monitor. These monitors are auto GCs, which provide data that are appropriate for comparison to the short-term AMCV and for averaging for comparison to the long-term AMCV. At BP’s 31st Street Monitor, the 2003 annual average benzene concentration was 1.6 ppbv, though it should be noted that this was an incomplete year of data (the TCEQ established an 85 percent completeness objective for industry-sponsored monitors). The annual average concentration was 1.7 ppbv in 2004 and increased to 2.7 ppbv in 2005. In 2006, the annual average concentration decreased to 1.7 ppbv, but still exceeded 1.4 ppbv. In 2007, the annual average concentration decreased to 1.0 ppbv and has remained at or below the long-term AMCV, with 0.8 ppbv in 2008, 1.4 ppbv in 2009, 0.4 ppbv in 2010, and 0.3 ppbv in 2011. The rolling 12-month average as of April 15, 2012, was 0.4 ppbv at the 31st Street Monitor, also indicating sustained improvement. The annual average benzene concentration at Marathon’s 11th Street Monitor was below the long-term AMCV in 2003 at 0.9 ppbv. In the years 2004 – 2007, the data for each calendar year was incomplete (monitoring was conducted October 2004 to October 2005, January 2006 to January 2007, and April 2007 to November 2007). These data did not meet the 85 percent completion requirement for calendar years 2004 – 2007, yet for the data that were validated, the average concentrations were 1.9 ppbv, 2.1 ppbv, 2.1 ppbv, and 2.2 ppbv, respectively. On November 5, 2007, the monitor was moved one block north to the corner of 11th Street South and 6th Avenue South. In the years 2008 and 2009, the annual average benzene concentrations exceeded the long-term AMCV with 1.8 ppbv and 1.6 ppbv, respectively, and the validated data met the required data completeness specifications. In 2010, for the first time in several years, the annual average benzene concentration was below the long-term AMCV at 0.9 ppbv. In 2011, the annual average concentration was also below the long-term AMCV at 0.8 ppbv. The rolling 12-month average concentration was 0.9 ppbv as of February 29, 2012, indicating sustained improvement. BP’s Logan Street Monitor began providing data in April 2010. The average concentration for the available 2010 data was 0.6 ppbv, but not enough data were 15 collected for the year to be considered complete. The 2011 average annual benzene concentration was below the long-term AMCV at 0.5 ppbv. The rolling 12-month average concentration was 0.6 ppbv as of April 15, 2012. Even the BP On-Site Monitor shows an improvement in air quality with a 2011 annual average benzene concentration of 0.8 ppbv. As discussed previously in this document, BP’s on-site monitor was installed to provide upwind concentrations and better pinpoint benzene sources, but does not provide data that is representative of community exposure due to its specific on-site location. Yet, the data indicates that the annual average of this site monitor was below 1.4 ppbv in 2011. Community Monitors Several of the companies in the area, including BP and Marathon, pay a third party contractor to collect data at four monitoring locations within the Texas City community. As discussed previously, this monitoring network consists of the 34th Street, 2nd Avenue, Avenue A, and North Site Monitors and is known as the Texas City/La Marque Community Air Monitoring Network. The third party contractor reports these data to the TCEQ on a periodic basis, and a summary of these reported data is provided here. Although the TCEQ did not evaluate the data specifically for the purposes of delisting Texas City from the APWL, the TCEQ is providing the information in this proposal because many individuals will likely be interested in the results from these monitors. The first complete year of data collected at the 34th Street Monitor was 2004, in which the annual average benzene concentration was 1.6 ppbv. The annual average benzene concentration improved in 2005 and was reported as 0.8 ppbv, below the long-term AMCV of 1.4 ppbv. The annual average concentrations were reported under the AMCV in all subsequent years, with 0.4 ppbv in 2006, 0.3 ppbv in 2007, 0.2 ppbv in 2008, 0.2 ppbv in 2009, 0.2 ppbv in 2010, and 0.2 ppbv in 2011. The average benzene concentrations at the Avenue A, 2nd Avenue, and North Site have been reported below 1.4 ppbv since 1994. Monitored Trends Figure 4, Annual Average Benzene Concentrations, demonstrates the downward trends in ambient benzene concentrations observed at all active Texas City monitors. These downward trends represent a significant improvement in air quality. The monitoring data show that ambient concentrations have remained below the long-term AMCV (represented by the dashed line) at each monitoring location, including the active BP on-site auto GC monitor, for two consecutive years (2010 – 2011). Additionally, as discussed previously, available rolling 12-month average concentrations at BP’s 31st Street Monitor, at Marathon’s 11th Street Monitor, and BP’s Logan Street Monitor indicate sustained improvement. 16 Figure 4: Annual Average Benzene Concentrations 3.0 2.5 Ball Park BP 31st Street 2.0 BP Logan Street Marathon 11th Street 1.5 2nd Avenue 34th Street 1.0 Avenue A North Site 0.5 0.0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 TCEQ Determines that Monitored Concentrations are Below a Level of Potential Concern Conducting air monitoring enables the TCEQ to accurately characterize chemical concentrations in the ambient air of communities in order to assess the potential for adverse health effects in the general public. The TCEQ is able to evaluate an extensive amount of monitoring data from several stationary monitors in the Texas City area— several of which are auto GCs that measure ambient concentrations every hour. The TCEQ has conducted multiple health effects evaluations of the ambient data collected at the Texas City monitors. The data show that, consistently, annual average concentrations show a significant improvement in air quality, decreasing to levels below those of potential long-term health concern. All monitors demonstrate that the annual average benzene concentrations have remained below the long-term, health-based AMCV of 1.4 ppbv for two consecutive years, and rolling 12-month averages also remain below the AMCV, indicating sustained improvements in air quality. 17 Figure 5: 2010 and 2011 Average Benzene Concentrations Below Level of Concern at all Monitors 1.8 1.6 1.4 Ball Park 1.2 BP 31st Street BP Logan Street 1.0 Marathon 11th Street 0.8 2nd Avenue 0.6 34th Street Avenue A 0.4 North Site 0.2 0.0 2009 2010 2011 The TCEQ previously conducted source determinations to identify the primary benzene contributors in the Texas City APWL area, and these companies have implemented significant equipment improvements. Certain companies that were previously identified as primary benzene contributors continue to use the industry-sponsored auto GCs for rapid notification of elevated benzene concentrations, enabling them to make repairs quickly and ensure that benzene emissions are mitigated. As such, the TCEQ is confident that the annual average benzene concentrations will be maintained below the AMCV. The TCEQ therefore determines that monitored concentrations can reasonably be expected to be maintained below levels of potential concern, and the TCEQ is proposing to remove benzene in Texas City from the APWL. 18 Public Comment Period The TCEQ will accept comments on the proposed delisting of Texas City from the APWL for the air toxic benzene. Interested persons may send comments to APWL@tceq.texas.gov or may send comments to the APWL coordinator at the following mailing address: Ms. Tara Capobianco, P.E. Air Pollutant Watch List Coordinator Texas Commission on Environmental Quality Air Permits Division MC-163 P.O. Box 13087 Austin, Texas 78711-3087 The comment period began on March 11, 2013, and the TCEQ will accept comments through April 26, 2013. Any questions regarding the proposed delisting or the APWL process may be forwarded to Ms. Capobianco at (512) 239-1117. Public Meeting The TCEQ will conduct a public meeting to receive comments on the proposed delistings of Texas City from the APWL for the air toxics benzene and hydrogen sulfide. The public meeting will be held on Thursday, April 11, 2013, at 6:00 p.m. at the Nessler Center Wings of Heritage Room, located at 2010 5th Avenue North, Texas City, Texas. The TCEQ will give a short presentation of the delisting of both benzene and hydrogen sulfide at 6:00 p.m. After a short question and answer session, the TCEQ will officially open the public meeting. The public meeting will be structured for the receipt of oral or written comments by interested persons. Individuals may present statements when called upon in order of registration. Open discussion within the audience will not occur during the public meeting; however, the TCEQ staff will be available to discuss the proposed delistings and answer any additional questions after the meeting. Persons who have special communication or other accommodation needs who are planning to attend the meeting should contact the Office of the Chief Clerk at (512) 2393300 or 1-800-RELAY-TX (TDD) at least one week prior to the meeting. 19