System vs Syllabus

advertisement

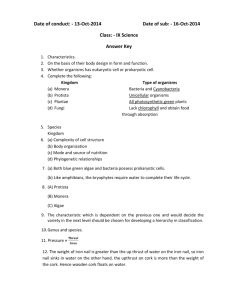

System vs Syllabus: a comparison between Meyer’s 1560 and 1570 rappier texts As a professional educator as well as a long-time amateur martial arts instructor, one of the issues that fascinates me about the historical fighting manuscripts is their approach to teaching. Broadly speaking, there are two types of texts: a) “Reference” texts which attempt to preserve a system of fighting b) “Teaching” texts which attempt to sequence the teaching of a weapon or style Reference texts aim to present everything of importance, aiming to tie ideas together, or to present memory cues for techniques learnt through physical instruction. For instance, the early German corpus revolves around the Lichtenhauer verses, which are mnemonic in nature. Terms in the verses are not explained, and the verses can be broken down into sections which do not necessarily link to ideas previously mentioned. Each subsequent author added a commentary or “glossa” to the verses, but retained the sequence of verses. Such a reference text works well for a reader already submerged in the art illustrated, but is not necessarily the ideal vehicle for teaching a raw beginner. A teaching text, on the other hand, aims to present material in a sequence to facilitate learning. Ideas are introduced in order from simple to complex, each building on the previous work. Many works of the 16th and later centuries are built on this model, reflecting a change in mindset by the writers from preserving an art to transmitting an art. Both types of text have their strengths and weakenesses. In the same way I keep reference books for mathematical operations or geological materials, a HEMA reference text covers the entirety of a system, and gives you a lot of technical information. However, I prescribe teaching texts for my undergrad students, as the volume of information in a reference text often obscures the important points a student must learn. Many of the best texts incorporate both teaching and reference material, making these essential reading for the HEMA interpreter and teacher. Joachim Meyer’s “rappier” or sidesword texts provide an ideal example of the difference between these two approaches. Meyer wrote several texts on the rappier during his lifetime and so it is possible to compare and contrast the same weapons system presented in two different ways. Whereas Meyer’s longsword texts often consciously mirror the traditional Lichtenauer corpus, the rappier system is essentially a “new” art, without a large number of accepted technical terms, and without a pre-existing group of practitioners. Thus, Meyer spends significant time describing actions with the weapon, making these texts a valuable source for the interpreter. Meyer’s 1560 rappier text: the systematic approach Meyer’s early text on the rappier is purely systematic. A guard is defined, potential parrying techniques are listed, and then suitable ripostes are listed. It is possible to present this material in a synoptic chart: Guard Possible Parries Cutting Off Suppressing Ripostes 1560 Reference High Thrust 71 l Low Thrust 70 l Inside Cut 71 l (with feint) Outside Cut 71 l Straight Cut 70 l High Thrust 71 r Low Thrust 71 r Inside Cut 72 l (with follow-up) Outside Cut 71 r Straight Cut High Thrust Low Thrust Going Through Inside Cut Outside Cut Straight Cut Nebenhut High Thrust 72 l Low Thrust Hanging Inside Cut 72 l Outside Cut 72 l (with feint) Straight Cut High Thrust Low Thrust Taking out with Long Edge Inside Cut Outside Cut Straight Cut After detailing the possible options from a particular guard, Meyer then gives selected examples to illustrate the techniques (listed in the fourth column). Thus, it is possible to use the 1560 text to summarise the rappier system as follows: a) There are 7 guards, presented in order as: i. Nebenhut ii. Wechsel iii. Right Ochs iv. Left Ochs v. Eisenpfort vi. Langenort vii. Pflug b) There are 6 different parrying techniques listed, but some techniques are unusable from some guards. The techniques named are: i. Cutting Off/Away ii. Suppressing iii. Going Through iv. Hanging v. Taking out with the Long Edge from above vi. Taking out from below with the Short or Half Edge vii. Setting Off c) After parrying, the follow-up strike can be one of five strikes: i. A thrust from above ii. A thrust from below iii. A cut from the inside iv. A cut from the outside v. A vertical cut straight down d) Attacking sequences are dealt with last On the face of it, the system presented in the 1560 system is extremely simple, with only a limited number of techniques to learn. In practice, however, selecting the right parrying technique and right counter attack adds a lot of complexity to the system. For instance, if an opponent attacks while you are in Nebenhut, your choice in technique is dictated by distance, timing, and attitude. Similarly, choosing to counter with a thrust from below or an inside cut will depend on the circumstances. An example of this complexity can be found in the first set of counters, those done after cutting away the incoming attack (an attack to your left in this case). After parrying, you can immediately counter with a thrust from below, a straight vertical cut to the head, a cut to his inside, and (with some practice at the body mechanics), a thrust from above left. However, how do you cut to his outside? Meyer’s example shows that he sets this cut up by threatening a cut to the inside, but then pulling away and cutting from the outside. Thus, feints and deceptions form an integral part of the system. Meyer’s 1570 rappier text: the teaching syllabus Meyer’s 1570 rappier text can be broken down into four portions: a glossary, a set of sequenced teaching drills, an advanced commentary, and a section on rappier and dagger/cloak. Though the glossary is of great use (especially with interpreting the 1560 text), my focus here is on the teaching drills, presented in the second part of the treatise. Unlike in the 1560 text, Meyer does not list guards and their appropriate techniques. Instead, Meyer presents a sequence of drills building in complexity. Techniques are introduced one by one and discussed in detail, but all options from a particular position are not detailed. This approach can be shown as a flowchart: Figure 1: the first action from Straight Parrying In the first device shown in figure 1, a simple linear sequence is given. You are attacked, you parry and launch a counter-attacking thrust. This can be done against attacks from the left and right, thrust or cut, provided the attacks come in at the head or upper body. The second device (figure 2) adds another layer to the first sequence. In this device, the attack is parried as before, but the attacker pulls away and cuts to other side before the counter attack can be delivered. This necessitates further parrying, until the attacker tires and a countercut can be launched. Subsequent devices (not shown) deal with attacks that come in from below, or drift down below your hand, and involve modifying your actions to deal with these threats. Thus, Meyer details possible counters to all possible attacks, building the sequence up. The next layer of complexity is added when Meyer deals with the aftermath of the counter attack. In devices following on from the basic setup, Meyer details how to maintain the attack when the opponent parries the counterattacking thrust (figure 3). Meyer offers three ways to defeat the opponent’s parry: turning the sword over the opponent’s blade for a high thrust, changing through under the opponent’s blade, or feinting a change and attacking back at the first target. Thus, the approach in the 1570 rappier text is essentially to build up the fighter’s skills systematically. First, basic parry-riposte technique is taught, then attacking technique is taught. Further sections detail using the cut as a counter attack, advice on avoiding deception, advice on attacking a defensive opponent, and then a variety of different techniques to use in different situations. Figure 2: How to parry multiple attacks . Figure 3: Maintaining the initiative after a counterattack Summary Meyer’s two rappier texts present a very similar system, but from two very different viewpoints. The early 1560 text allows the reader to understand the system in its entirety, where each guard allows certain defensive actions, and each defensive action can be followed with one of five counter attacks. The 1570 text introduces techniques in a sequence building from basic moves to more advanced techniques, showing the skill progression a student needs to follow to master the weapon. Hopefully this article has shown how a teacher can use these two texts to complement each other, and I have given instructors some ideas on how best to teach the material.