Humphrey Foote v2 - American Intellectual Property Law Association

advertisement

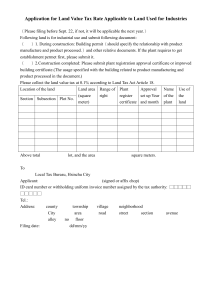

International IP Protection for Plants Dr Humphrey Foote humphrey.foote@ajpark.com AJ Park I. Introduction Protecting plant-based intellectual property internationally presents unique challenges. The law around what and how plant subject matter can be protected in different countries varies considerably, and in some countries options are quite limited. Creative approaches are therefore beneficial to maximise protection in the jurisdictions in which protection is desired. Described here are some of the available options for protecting both genetically modified (GM) and non-GM plants in 16 of the most important markets for such plants. The chosen jurisdictions are Australia, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Europe, India, Indonesia, Japan, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand, United States, Vietnam and South Africa. II. Protecting genetically modified (GM) plants A. Protecting GM plants with patents Generally the broadest protection for GM plants and products is provided by patents. However the extent of patent protection available varies significantly between countries. The author believes it is important to be aware of the limitations and challenges, and to have a global focus from the outset, when drafting patents which may ultimately be filed many different jurisdictions. 1. Patent eligible subject matter The issue of patent eligible subject matter has recently come to prominence with the decision, in June this year, of the US Supreme Court in Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc. (the "Myriad" case). As has been well publicised, the Court ruled that naturally occurring DNA, even in its isolated form, is no longer patent eligible subject matter in the US, but that cDNA with some exceptions is. The Myriad decision has prompted a great deal of 1 discussion and blogging concerning how, and if, various gene-based technologies can be protected in the United States now that naturally occurring DNA is no longer patentable. It is interesting to note that the United States is not the first territory to take this position. Those of us who have been protecting GM plant technology around the world have likely had to deal with the exemption of isolated naturally occurring DNA from patent protection in some countries for quite some time. Table 1 below provides general guidelines to what is patent eligible subject GM plant subject matter in the listed countries. There may be subtle exceptions, for example based around whether or not the plant parts and seeds can be used to reproduce further plants. Furthermore, patent offices and/or courts in some countries sometimes adopt unexpected interpretations of the wording of the relevant statutes. Therefore this information should be considered as a guide only. Table 1 – Patent eligible subject matter for GM plants internationally Country Isolated DNA sequences from plants Modified sequences / expression cassettes with heterologous sequence elements Transgenic plant cells Australia yes yes Argentina no Brazil Transgenic plants Transgenic plant parts (e.g. seeds) Methods for producing transgenic plants yes yes yes yes yes no no no yes no yes no no no yes Canada yes yes yes no no yes Chile yes yes no no no yes China yes yes yes no no yes Europe yes yes yes yes yes yes 2 India no yes no no no no Indonesia yes yes yes yes yes yes Japan yes yes yes yes yes yes New Zealand yes yes yes yes yes yes Philippines yes yes yes no no yes Thailand no yes no no no yes United States no yes yes yes yes yes Vietnam yes yes yes yes yes yes South Africa yes yes yes yes yes yes 2. Some observations with reference to Table 1 Some observations based on the author's experiences and with reference to Table 1 are discussed below. a. Value in a claim to a construct including heterologous elements A claim to the sequence that is used to transform the plant can be the most desirable claim to have, especially in situations where transgenic plants are not patentable. In some cases a claim to the sequence may also protect a plant or plant part transgenic for the sequence. As mentioned above, and shown in Table 1, several countries do not allow protection of isolated naturally occurring DNA. It is worth noting that in all countries listed above a claim to an expression cassette including a heterologous element (e.g. a promoter or terminator heterologous to the coding sequence) is eligible. Therefore such a claim is certainly worth including. In theory use of the heterologous element such as a promoter could be avoided by transforming the coding sequence alone into the genome of the plant where its expression could be controlled by an endogenous promoter. However this would be relatively unusual and most expression cassettes used to produce GM plants include a heterologous promoter anyway. Claims to such constructs can also be useful for overcoming novelty objections in jurisdictions such as Europe where examiners often object to claims generally directed to plants simply "comprising" a specified plant polynucleotide on the basis that such plants are not distinguished from wild-type plants. 3 Similarly, post Myriad, the author has received s101 objections from examiners at the USPTO arguing that plants simply defined as comprising a specified plant polynucleotide are not distinguished from naturally occurring plants. Again having the option to amend to include a heterologous element in the expression cassette can be useful to overcome such objections. b. Good method claims are important It is also worth noting that while in many countries at least some GM plant subject matter is excluded from patentability, all countries in the table with the exception of India allow claims to methods for producing transgenic plants. Therefore good method claims are important. However in some countries examiners may still object if they consider such claims encompass the transgenic plants themselves if these are not patent eligible. Therefore alternative method claims for example directed to altering a phenotype in a plant, or growing/cropping plants under certain conditions, are also be worth including. c. Conclusion Exclusions of certain GM plant materials as eligible subject matter, as illustrated in the Table 1, highlights the need for multiple further claims formats (beyond the scope of this paper) when filing patents for GM plants internationally. This is especially true when considering the challenges to protecting subsequent generations of the primary transformed plants, and protecting material harvested from the GM plants. B. Protecting GM plants with "plant variety-type protection" Individual varieties of GM plants can also be protected by "plant variety-type protection". The term "plant variety-type protection" as used here, is intended to include plant variety protection and plant patents in the United States, as well as the similar plant variety rights and plant breeders' rights protection provided in other countries. Plant variety-type protection is typically limited to a single variety, and so is generally much narrower than the classical type gene-based patent protection for GM plants. In addition plant variety-type protection in not available for every species in every country. However plant variety-type protection does have the advantage that no inventive step is required among other advantages. In many countries a degree of regulatory approval for a GM plant variety is required before a plant variety-type application can progress. It is therefore often important to monitor dates of first sale of the variety to ensure that there is sufficient time to consider obtaining such regulatory approval within filing time limits typically governed by the novelty requirements for the plant variety-type protection in the chosen territories (see Table 3 below). 4 C. Protecting GM plants with "event" patents Another option for protecting GM plants in addition to the typical claims built around the sequence transformed is to protect a particular transformation event. The event may be defined in part by the sequences flanking the inserted DNA. This type of protection is also narrower than the classical gene sequence-based patents for GM plants, but can be broader than plant variety-type protection because such patents can encompass plant produced through further crossing that also contain the same event. This type of protection may therefore be particularly useful for species that are often used to produce hybrids. D. Combining protection methods to extend protection for GM plants The approaches described in sections A, B and C above can be used in combination to effectively extend the term of patent protection for particularly preferred GM plants. For example a particularly beneficial variety or transformation event could be protected by "plant variety-type" protection or in an "event" patent respectively, beyond the term of an initial broader gene-based patent. This approach however requires careful management/planning to ensure that the novelty/inventive step requirements of the later plant variety-type protection or event patent are met III. Protecting non-GM plants Protecting non-GM plants offers further challenges with some but not all of the approaches discussed above being available for such traditionally bred plants. A. Protecting non-GM plants with patents Because patent protection is generally broader than plant variety-type protection, patent protection for non-GM plants, or methods for producing them, is an attractive option. However such protection is not available in all jurisdictions. In some countries plant varieties are excluded from patent protection. In others countries plant varieties can be protected by either patent of plant variety type protection. Table 2 below shows summarises this information for the same 16 jurisdictions in Table 1. Again this information should be treated as a guide only. Table 2 – Availability of patent protection for non-GM plants and methods for their production, and for plant varieties. Country Non-transgenic plants Refined methods* for the breeding of nontransgenic plants Plant varieties Australia Yes Yes No 5 Argentina No Yes No Brazil No Yes No Canada No** Yes No Chile No Yes No China No Yes No Europe Yes No No India No No No Indonesia No No No Japan Yes Yes Yes New Zealand Yes Yes Yes Philippines No No No Thailand No Yes No United States Yes Yes Yes Vietnam Yes Yes No South Africa No No No *For methods for production of non-GM plants to be protectable by patents, additional technical steps beyond standard breeding practices, such as steps that cannot occur in nature, may be required. **In Canada, a claim to a non-transgenic cell is eligible, and should be enforceable against a plant comprising the cell B. Protecting non-GM plants 'plant variety-type' protection Varieties of non-GM plants, as well as GM-plants as discussed above, are of course protectable by plant variety-type protection. As noted above however, plant variety-type protection in not available for every species in every country. Table 3 below summarises some relevant information for the same 16 jurisdictions discussed above. Again this information should be treated as a guide only. 6 Table 3 – Novelty provisions and term of protection for plant variety-type protection. Country Protection Plant breeder's right Novelty provisions No sale in AU more than 1 year before filing No sale abroad more than 6 years (trees/vines**) or 4 years (other plants) before filing Term 20 years from grant 25 years from grant (trees and vines) Plant variety protection No sale in AR before filing. No sale abroad more than 6 years (trees/vines) or 4 years (other plants) before filing Between ten and twenty years, depending of the species or group of species. Plant variety protection No sale in BR more than 1 year before filing No sale abroad more than 6 years (trees/vines) or 4 years (other plants) before filing 15 years from Provisional Protection Certificate 18 years from Provisional Protection Certificate(trees and vines) Plant breeder's right No sale in CA prior to effective date of application No sale abroad more than 6 years (woody plants) or 4 years (other plants) before filing. 18 years from grant No sale in CL more than 1 year before filing No sale abroad more than 6 years (trees/vines) or 4 years (other plants) before filing 15 years from grant 20 years from grant (trees and vines) Plant variety protection No sale in CN more than 1 year before filing No sale abroad more than 6 years (trees/vines) or 4 years (other plants) before filing 15 years from grant 20 years from grant (trees and vines) Community plant variety right No sale in EP more than 1 year before filing No sale abroad more than 4 years or 6 years (trees and vines) before filing 25 years from grant (other) 30 years from grant (potatoes, trees and vines) Plant variety protection No sale in IN more than 1 year before filing No sale abroad more than 4 years or 6 years (trees and 18 years from grant ( trees and vines) 15 from the date of notification of that variety Australia Argentina Brazil Canada Chile China Europe India 7 vines) before filing by the Central Government under the Seeds Act, 1966 for extant varieties 15 years from grant (other) Plant variety protection No sale in ID more than 1 year before filing No sale abroad more than 4 years (seasonal plants) or 6 years (annual plants) before filing 20 years from grant (seasonal plants) 25 years from grant (annual plants) Plant variety protection No sale in JP more than 1 year before filing No sale abroad more than 6 years (trees/vines) or 4 years (other plants) before filing 25 years from grant 30 years from grant (trees and vines) Plant variety right No sale in NZ more than 1 year before filing No sale abroad more than 6 years (woody) or 4 years(non-woody) before filing 20 years from grant (nonwoody) 23 years from grant (woody plant) Plant variety protection No sale in PH more than 1 year before filing No sale abroad more than 4 years or 6 years (trees and vines) before filing 20 years from grant 25 years from grant (trees and vines) Plant variety protection No sale in TH or abroad more than 1 year before filing -12 years if yield characteristics within 2 years -17 years if yield characteristics in more than 2 years -27 years for woody plants that yield characteristics in more than 2 years Plant patent - Asexually reproduced (except tubers) As for utility patents. 1 year grace period 20 years from filing Plant variety protection – Sexually reproduced No sale in US more than 1 year before filing 20 years from grant Indonesia Japan New Zealand Philippines Thailand United States No sale abroad more than 4 years or 6 years (trees and vines) before filing Plant variety protection Vietnam No sale in VN more than 1 year before filing No sale abroad more than 4 years or 6 years (trees and 8 25 years from grant (trees and vines) 20 years from grant 25 years from grant (trees and vines) vines) before filing Plant breeders' rights South Africa No sale in ZA more than 1 year before filing No sale abroad more than 4 years or 6 years (trees and vines) before filing 20 years from grant 25 years from grant (trees and vines) * "Sale" in many countries includes an "offer for sale". "Sale" may also be limited to sale of reproductive material. ** "Vine" in many countries is interpreted as "grapevine" IV. Conclusion The information above provides an overview of options for protecting plant intellectual property in 16 of the most important jurisdictions for such material. This information is by no means comprehensive, but is intended to highlight some of the important differences between the jurisdictions that plant biotechnology IP practitioners should be aware of or wary of when considering IP protection strategies for their companies or clients. V. Acknowledgement The author acknowledges the following for helping provide some of the information with respect to the countries discussed above: Marval, O'Farrell & Mairal - Argentina, Dannemann Siemsen Brazil, Sim & McBurney, Smart and Biggar - Canada, Estudio Villaseca - Chile, Melvin Li China, Kan & Krishme - India, Lumenta, Sitorus & Partners - Indonesia, TMI Associates Japan, SyCipLaw - The Philippines, Domnern,Somgiat & Boonma - Thailand, Greenlee Sullivan Winner - United States, VCCI-IP CO., LTD - Vietnam, Adams Adams - South Africa, http://www.katzarov-manual.com, Karl Rogers and Marcia Rosenfeld. VI. Disclaimer While the author has tried to ensure that the information provided is accurate, the information provided is not a substitute for legal advice. The author, the author's firm, and those acknowledged above are not responsible for any errors or omissions. Humphrey Foote (humphrey.foote@ajpark.com) – August 2013 9