Evidence-Based Medicine May 22, 2009 Sally Ravanos, MD Oral

advertisement

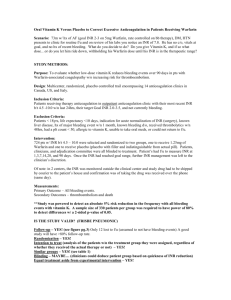

Evidence-Based Medicine May 22, 2009 Sally Ravanos, MD Oral Vitamin K Versus Placebo to Correct Excessive Anticoagulation in Patients Receiving Warfarin Crowther et al. Ann Intern Med.2009; 150: 293-300. Study Design: Multicenter , randomized, placebo-controlled trial Study Participants: 724 patients in 14 anticoagulation clinics in Canada, US, and Italy recruited between Sept 2004 and June 2006 Inclusion criteria: Patients with target INR between 2.0 and 3.5 presenting for routine INR monitoring, not actively bleeding Exclusion criteria: Age <18years, imminent discontinuation of warfarin therapy, life expectancy < 10 days, any indication for acute reversal of INR (such as surgery), severe liver disease, h/o major bleeding event within one month, known bleeding disorder, receipt of thrombolytic therapy in past 48 hours, platelets < 50,000, inability to take oral medications, known allergy to vitamin K, and inability to return for lab or clinical monitoring Study Protocol: Patients who met inclusion criteria and consented for participation were randomized to receive 1.25mg vitamin K or an identical placebo pill and were then followed up by telephone or in person on day 1, 3, 7, 14, 28, and 90 after randomization. Signs and symptoms of bleeding were assessed at each follow-up. Primary outcome measure: The frequency of bleeding events during the 90 days after randomization. Major bleeding=fatal bleeding, bleeding requiring transfusion of 2 or more units of PRBCs, bleeding resulting in therapeutic intervention (e.g. endoscopy), or objectively confirmed bleeding into a closed space Minor bleeding=bleeding resulting in a medical assessment Trivial bleeding=all patient-reported bleeding events that did not result in a medical assessment **All types of bleeding were considered together in this study. Secondary outcome measures: The frequency of major bleeding events, confirmed arterial or venous thromboembolism, and death during the 90 days after randomization. All bleeding and thromboembolic events were investigated by an independent committee blinded to treatment allocation. Results (see tables 2 and 3, p. 296-297) --Almost 2/3 of patients in the study had INRs between 4.5 and 6.0 at the time of randomization. --In the 90 days after randomization, 56 of the 355 patients given vitamin K had a bleeding event (15.8%); 60 of the 369 patients given the placebo had a bleeding event (16.3%). --Major bleeding events occurred in 9 patients (2.5%) in the vitamin K group and 4 patients (1.1%) in the placebo group. --In the first 7 days, bleeding events occurred as follows: -34 events occurred between INR 4.5 and 6.0 (12 vitamin K, 22 placebo) -17 events occurred between INR 6.1 and 8.0 (9 vitamin K, 8 placebo) -11 events occurred between INR 8.1 and 10.0 (7 vitamin K, 4 placebo) --8 lost to follow up in vitamin K group; 4 lost to follow up in placebo group. --Over half of bleeding events occurred in the first 7 days after randomization. --INR response was brisker in the vitamin K group, as is expected. This is evidence that subjects took the study drug. --10 of the 13 major bleeding events occurred in patients over age 70. Vitamin K Placebo Any bleeding event 56 60 No bleeding event 299 309 CER= 60/369=16.3% RRR=(16.3%-15.8%)/16.3%=3.1% EER= 56/355=15.8% ARR=16.3%-15.8%=0.5% There was no statistically significant difference in frequency of bleeding events in the vitamin K group vs the placebo group. Are the results valid? Was the assignment of patients randomized? Yes, randomization was performed via a computer-generated random number table. Patients were randomized to receive either 1.25mg vitamin K or an identical placebo pill. Was the randomization list concealed? Yes, randomization was determined by a computer. Study personnel handed out envelopes containing either vitamin K or placebo without knowing what was in the envelope. Was follow-up of patients sufficiently long and complete? Yes, the patients were assessed by telephone and in person on days 1, 3, 7, 14, 28, and 90 after randomization. Each follow-up consisted of evaluation for signs and symptoms of bleeding or thromboembolism. Further INR checks and changes in warfarin dosing were left up to the patients’ personal physician. Were all patients analyzed in the groups to which they were randomized? Yes, this was an intention to treat analysis. 724 patients were randomized (355 to vitamin K, 369 to placebo). 8 were lost to follow up in the vitamin K group; 4 were lost to follow up in the placebo group. Were patients and clinicians kept blind to treatment? Yes, neither was aware of the content of the drug given at the time of treatment. Were the groups treated equally, apart from the experimental treatment? Yes. Were the groups similar at the start of the trial? Yes. See Table 1, p. 296. Can this evidence be applied to our patient population? Yes, supratherapeutic INRs occur frequently without any evidence of active bleeding. The use of vitamin K to lower INR is well established. Strengths -Randomization with concealed allocation -Blinding of all parties involved -Intention to treat analysis -Complete follow-up in almost all patients Weaknesses -Insufficient power to detect differences in the frequency of major bleeding events -No control over open label vitamin K administration by subjects’ PCP after initial randomization and how that might affect bleeding event rates -Some of the data was collected by telephone survey and not in person Conclusion Low dose oral vitamin K did not reduce the frequency of bleeding events in patients taking warfarin with an INR between 4.5 and 10. Further Studies A similar study with INR greater than 10 and vitamin K 2.5mg is currently being performed and is to be published soon.