MS Word - Winona State University

advertisement

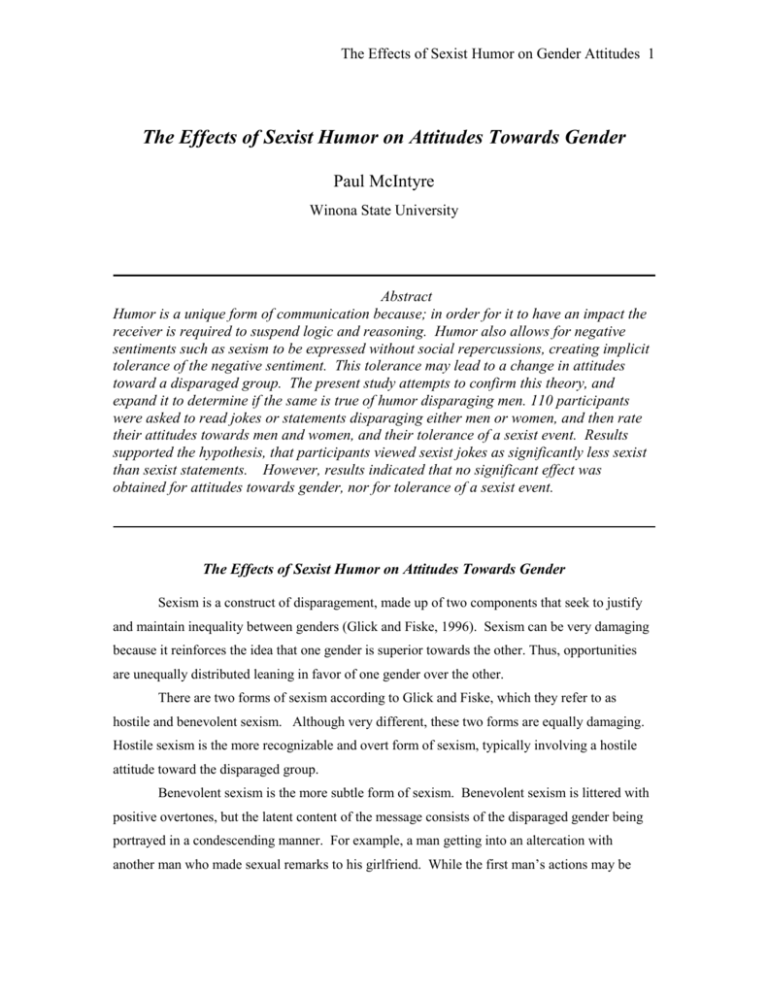

The Effects of Sexist Humor on Gender Attitudes 1 The Effects of Sexist Humor on Attitudes Towards Gender Paul McIntyre Winona State University Abstract Humor is a unique form of communication because; in order for it to have an impact the receiver is required to suspend logic and reasoning. Humor also allows for negative sentiments such as sexism to be expressed without social repercussions, creating implicit tolerance of the negative sentiment. This tolerance may lead to a change in attitudes toward a disparaged group. The present study attempts to confirm this theory, and expand it to determine if the same is true of humor disparaging men. 110 participants were asked to read jokes or statements disparaging either men or women, and then rate their attitudes towards men and women, and their tolerance of a sexist event. Results supported the hypothesis, that participants viewed sexist jokes as significantly less sexist than sexist statements. However, results indicated that no significant effect was obtained for attitudes towards gender, nor for tolerance of a sexist event. The Effects of Sexist Humor on Attitudes Towards Gender Sexism is a construct of disparagement, made up of two components that seek to justify and maintain inequality between genders (Glick and Fiske, 1996). Sexism can be very damaging because it reinforces the idea that one gender is superior towards the other. Thus, opportunities are unequally distributed leaning in favor of one gender over the other. There are two forms of sexism according to Glick and Fiske, which they refer to as hostile and benevolent sexism. Although very different, these two forms are equally damaging. Hostile sexism is the more recognizable and overt form of sexism, typically involving a hostile attitude toward the disparaged group. Benevolent sexism is the more subtle form of sexism. Benevolent sexism is littered with positive overtones, but the latent content of the message consists of the disparaged gender being portrayed in a condescending manner. For example, a man getting into an altercation with another man who made sexual remarks to his girlfriend. While the first man’s actions may be The Effects of Sexist Humor on Gender Attitudes 2 well intentioned (getting the other man to leave her alone, protecting her), his actions also imply that the woman is insufficiently equipped to deal with the situation, and needs a man’s protection. A study conducted by Inman and Baron (1996) indicates that people are most likely to call a potentially prejudice instance prejudice when it involves a specific kind of perpetrator and a specific type of victim. To conduct this research Inman had participants read vignettes that were discriminatory towards women and men, and varied the perpetrator of the discrimination’s gender (male and female). Participants then placed each vignette into categorical piles based on similarities in the actor’s characteristics. Participants were more likely to place male-on-female (prototypical) discriminatory vignettes in the discrimination pile than place female-on-female vignettes (non-prototypical) in the discrimination pile. However, this was only true when females where being disparaged against. There was no significant difference between female-on-male discrimination, or on male-on-male discrimination. Their findings demonstrate that the template for sexism as a construct is typically exemplified in a prototypical manner (i.e. men disparaging women). Thus far I have discussed research that primarily examines sexism in the context of statements. The previously mentioned research begs the question; what role does the context of humor play in conveying a sexist message? I will now examine sexism in the context of humor. Sev’er and Ungar (1997) argued that humor serves as vehicle for the perpetuation of a power differential between males and females. Thus keeping the status of the female gender unequal to males. They assert that humor reinforces the differential by hiding under the guise of harmless fun. In order for this to be true, a person must assume that humor has the ability to negatively affect people’s attitudes toward a particular group. Research supports the assumption that people’s attitudes can be negatively influenced by humor. Hobden and Olsen (1994) found that participants who told jokes making fun of lawyers adopted a more negative disposition toward lawyers in general. In other words, a person’s attitude toward a particular group may be shifted negatively by telling jokes that make fun of that particular group. However, numerous studies have concluded that people will enjoy disparaging humor as long as they have predilection toward negative attitudes of that group (e.g., Ford, 2000; Hobden & Olsen, 1994). Under this assumption we can infer that many people do not have negative attitudes toward these groups, therefore most people engaging in disparaging humor may be looked upon unfavorably. Research conducted by Olsen, Maio, and Hobden (as cited in Ford, 2000) found that there was no consistent affect on people’s attitudes of a disparaged group when they were exposed to disparaging humor. Ford (2000) proposed an explanation for this finding; people with The Effects of Sexist Humor on Gender Attitudes 3 stable, internalized attitudes toward a traditionally disadvantaged group will not be affected by disparaging humor towards that group. His research supports his explanation. In his 2000 study, Ford assigned participants to condition based on their scores on a hostile sexism inventory. He then asked participants to rate the humorousness of sexist jokes in vignette form. The results indicate that when compared to subjects low in hostile sexism, participants high is hostile sexism deemed the disparaging jokes to be more humorous than neutral jokes and non-humorous sexist statements. High in hostile sexism participants were also more likely to be tolerant of a sexist event after exposure to sexist jokes, but not after sexist statements. Another study conducted by Bill and Naus (1992); found that when male participants perceived an incident of sex discrimination as humorous, they were more likely to consider the incident harmless. This finding may be explained by the uniqueness of humor as a form of communication. Humor is a distinctive medium of communication, in that it identifies itself through cues that tell the receiver not to analyze the message in a serious or critical manner. In a sense, humor is exempt from critical analysis as long as the receiver understands and interprets the cues that mark the message as a humorous communication (Attardo, 1993). Rouhana, (as cited in Ford, 2000) suggests sexist humor conveys a meta-message, which implies that sexism need not be taken seriously, compounded by the fact that humor inhibits the critical analysis of it’s message. This is especially problematic if the person receiving the message sets their standards of conduct based on the prevailing social norms of the situation (Ford, 2004). In an essay on disparagement humor, Ford (2004) proposed a prejudice norm theory; people who are high in prejudice beliefs set the parameters for appropriate conduct based on the external social norms. For example, a person may reserve a sexist joke for another time, after learning the person they are with is a feminist. Humor serves to change social judgment by manipulating the perception of the social context. Under this assumption, Ford believes that the rules change for a given context. Humor essentially blocks the rules that govern appropriate reaction to discriminatory statements from being activated. This broadens the definition of appropriate conduct, creating a norm of tolerance of discrimination. If this is true, than participants exposed to sexist statements will be limited by the rules of the appropriate conduct, and hence, be less tolerant of a sexist event than those exposed to sexist jokes. Similarly, participants who are exposed to sexist statements will be less likely to endorse sexist attitudes towards genders, than those exposed to sexist jokes. The present research is also interested in determining if participants exposed to sexist humor will rate jokes as less sexist, than participants exposed to similar sexist statements. Finally in order to test the assumption that The Effects of Sexist Humor on Gender Attitudes 4 sexism is only recognized as such in a prototypical situation this study attempts to determine if sexist statements against men are even considered sexism or if it is not even recognized as such. Another goal of the present study is to determine if sexist jokes against men will have the same hypothesized affect as sexist jokes belittling women; jokes will be viewed as less sexist compared to the sexist statements against men. Methods Participants The present study had 110 Winona State University undergraduates (79 women, 31 men) as participants. All participants were between 18 and 25 years of age. Students were enrolled in undergraduate psychology courses and received extra credit in their courses as compensation for their participation Materials Design. A 2X2 factorial with an independent control group was used to compare material gender (males/females) and material type (joke/statement). All material, with the exception of the control group, contained a sexist message. Independent variables. 7 paradigms that disparaged either males or females, in the form of either a statement or a joke were used to expose participants to sexism. An example of a typical joke about women would be: “Why haven’t any women been to the moon? Because it doesn’t need cleaning yet.” An example of a statement that was disparaging toward women would be: “Women are not as smart as men. Women may be intelligent, however they are not equivalent to men. They lack common sense intelligence, and are not as good at rational and critical thinking.” Jokes and statements that derogated men were similar to the two previous examples, however they were tailored to the male gender. The control paradigms contained jokes that were not disparaging toward a particular gender. An example is: “What did the drummer get on his ACT? Drool.” Jokes were taken from various Internet websites, and each joke appeared on at least two different websites demonstrating that the content of the joke was consistent, and reoccurring. Jokes were chosen under the criteria that they be: Humorous, disparaging The Effects of Sexist Humor on Gender Attitudes 5 toward a particular gender, not overtly sexual, not blatantly offensive, non-aggressive, and non violent. Statements were constructed from the content of the jokes. The implicit message that each joke conveyed was used in order to keep the sexist message consistent. Manipulation checks. Instructions required that each of the seven paradigms be analyzed on three different dimensions. Using a Likert type scale ranging from 0 (not at all humorous/sexist) to 5 (extremely humorous/sexist), participants were asked to indicate: how humorous the paradigm was and how sexist the paradigm was. The final dimension asked whom, if anyone, was the paradigm disparaging. The final dimension instructed participants to indicate men, women, or neither. Dependent measures. The dependent measures consisted of two scales designed to measure the extent of sexist attitudes of the participants. The first measure was titled Attitudes toward Gender and Society Inventory and was a compilation of 20 questions; the second measure was titled Tolerance of a Sexist Event and consisted of a sexist scenario and eight proceeding questions. Attitudes toward Gender and Society. This measure combined 20 items on one page taken from Glick and Fiske’s Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI, 1996) and the Ambivalence Toward Men Scale (ATMS, 1999). Both of these scales are designed to measure the hostile and benevolent sexism attitudes toward women (ASI) and men (ATMS). The measure consisted of questions such as, “Most women interpret innocent remarks or acts as being sexist” to measure hostile sexism. Benevolent sexism would be measured with the question “Women should be cherished and protected by men” for example. A hostile sexism question regarding men is “Most men sexually harass women, even if only in subtle ways, once they are in a position of power over them.” Of the 20 selected items, 10 were used for judging attitudes toward both males and females. There were five items that measured hostile sexism, and the remaining five measured benevolent sexism toward women (ASI). Similarly five measured benevolent sexism and the remaining five measured hostile sexism toward men. The four different measures were randomly placed throughout the page and each of the 20 questions was rated on a scale of 0 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). The Effects of Sexist Humor on Gender Attitudes 6 Tolerance of a Sexist Event. This was a scenario explaining a sexist situation that took place in a work office type setting. A woman was deprecated as being incompetent, for making a simple mistake, by a male co-worker while she had left the room to retrieve an item needed for a meeting. All the male co-workers in the room laughed at the disparaging remark, and an accompanying comment about the woman’s body. The items that followed the scenario were designed to measure how tolerant the participants were of the situation. Examples of the questions include: “How sexist does this situation seem?” “How offensive is the man’s statement?” “Do you agree that taking appropriate action would prevent further remarks made by the men in the office?” A scale of 0 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) was used to measure the degree to which the participants agree with the questions. Procedure Groups ranging from 1 to 10 participants were randomly assigned to one of the five conditions. After entering the lab area, participants filled out credit slips, which would later be turned in to their professors for extra credit. In addition participants signed informed consent forms, as the researcher gave a verbal description of the consent form. All participants were told in advance that the proceeding statements may be considered offensive, and those who found the materials offensive were allowed to stop at any time with no penalty toward their extra credit. Participants were given a copy of the directions and the researcher verbally explained the directions, instructing participants to rate the paradigms on the previously mentioned dimensions using the scales 0 to 5. Participants read the paradigms individually, and once they had completed indicating the humor, sexism, and appropriate group disparagement for all seven statements they indicated to the researcher that they had completed that portion of the experiment. Participants were then given the Attitudes Toward Gender and Society inventory, and the accompanying Tolerance of a Sexist Event Scenario. Once every individual in the group had finished both packets, they were asked if they found anything overly offensive. Participants were debriefed and thanked for their participation then were allowed to leave. The Effects of Sexist Humor on Gender Attitudes 7 Results Four participants had to be removed due to experimental error; another three participants were also removed from the final analysis because they did not use the proper scales to rate the humor and sexism of the jokes. All scales ranged from 0 to 5, with higher numbers indicating positive values. Results did not support the hypothesis; there was no difference across the conditions on endorsement of sexist attitudes. Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and F Statistics for the Manipulation Checks Condition Humor Sexism Gender Disparagement SW M=2.84 SD=0.18 M=0.22 SD=0.16 M=-0.65 SD=1.18 JW M=2.62 SD=0.17 M=0.22 SD=0.16 M=-0.65 SD=1.18 SM M=0.79 SD=0.15 M=3.90 SD=0.13 M=-6.43 SD=1.17 JM M=2.69 SD=0.18 M=2.43 SD=0.16 M=4.00 SD=1.21 C M=0.58 SD=0.18 M=3.52 SD=0.16 M=5.90 SD=1.45 Overall F F (4,105)=44.54,p =.0001 F (4,105)=44.54,p =.0001 F (4,105)=227.11, p =.0001 S-statement, J-joke, W-women, M-men, C-control. * Numbers that share a color are not significantly different from each other A 2X2 ANOVA was conducted to test the effects material gender and material type on sexist attitudes measured by a compilation of Glick and Fiske’s ASI and ATMS (Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to be .8428). Results indicated that there was no significant interaction, F(1,86)=1.187,p =.279. The results also indicate that there where not any significant main effects for material gender, F(1,86)=.022, p =.882, nor for material type, F(1,86)=.515, p =.475. A second 2X2 ANOVA was conducted to test the effects of material type and material gender on tolerance of a sexist event (Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to be .7129). Results did not support the hypothesis; there were no significant differences across the groups on their tolerance of a sexist event. Results indicate that there was no significant interaction F(1,86)=.004, p =.947, nor where there any significant main effects for material gender, F(1,86)=.006, p =.938, or for material type F(1,86)=.152,p =.698. The results of a one-way ANOVA support the hypothesis; groups found the jokes significantly more humorous than statements. Results revealed significant differences in humor The Effects of Sexist Humor on Gender Attitudes 8 ratings across conditions F(1,105)=44.55, p =.0001. Multiple comparisons show that joke paradigms were rated significantly funnier than statements (see figures 1& 2). A second one-way ANOVA supported the hypothesis; the conditions differed significantly on the ratings of sexism on the paradigms. Jokes were seen as significantly less sexist than statements. Results showed significant differences in sexism ratings across conditions F(1,105)=96.13 p =.0001. Multiple comparisons revealed that statements were significantly more sexist than jokes (see figures 1& 2). A third one-way ANOVA revealed significant differences on gender disparagement across conditions F(1,105)=227.12,p =.0001. Multiple comparisons show that subjects recognized anti-female material as such, but were less likely to recognize material that was anti-male as being anti-male (see figures 1&2) Figure 1. Mean rating of sexism and humor on a 0 to 5 point scale, by condition. Me a n Score on 0 t o 5 Like rt Sca le 5 4 3 2 1 Ave rag e Hu m o r 0 Ave rag e Sex is t SW JW SM JM C Co ndit ion A t-test conducted across gender revealed significant differences between male and female participants on the dimensions of humor and sexism. Overall, males (M=2.41, SD= 1.12) viewed the paradigms as significantly funnier than females(M=1.61,SD=1.26), t(68)= 3.29, p= .0008, and females (M=2.64, SD=1.44) considered the paradigms to be significantly more sexist than males(M=1.92, SD=1.60), t(108)=-2.29, p=.0118 (males- females). The Effects of Sexist Humor on Gender Attitudes 9 Figure 2. Overall average rating of humor and sexism scores by subject gender. Me a n Score on 0 t o 5 Like rt Sca le 2 .8 2 .6 2 .4 2 .2 2 .0 1 .8 1 .6 Ave rag e Hu m o r 1 .4 Ave rag e Sex is t Fem ale Ma le Subje ct ge nde r Discussion It was hypothesized that there would be differences seen between the conditions on their endorsement of sexist attitudes toward men and women, and their tolerance of a sexist event. More specifically, the hypothesis presumed that groups that received joke paradigms would be more likely to endorse sexist attitudes, and be more tolerant of the sexist event. However, the results provide evidence to the contrary. The hypothesis surmised that the joke paradigms would be seen as less sexist because the humor created greater acceptance of the sexist message, which the results support. We hypothesized that the joke paradigms that belittled men would be seen as significantly less sexist than the sexist statement paradigms degrading men. The results for men, mirror those of the women in terms of jokes being less sexist. Jokes that disparaged men were rated as significantly less sexist than statements that disparaged men, suggesting that sexism may not only work in a prototypical manner. The results not only contradict the prototypical view, but The Effects of Sexist Humor on Gender Attitudes 10 they also suggest that humor plays an important role in reducing the severity of a sexist message, perhaps more important than the prototypical view of sexism as a construct. One interesting result is that the statements that disparaged men were seen as slightly more sexist than the paradigms disparaging women, although this result was not significant. A possible explanation for such a counterintuitive finding would be the fact that the amount of women who participated in this study far outnumbered the amount of men (79 to 31). Because women are the typically disparaged group, when it comes to sexism, they may be in position where their individual experiences played a big factor in determining what constitutes sexism. This was the case with the present study, the scores attributed to the paradigms on sexism and humor differed significantly across gender. Men found things to be funnier, and consequently less sexist, while women had the opposite reaction. One plausible explanation for this discrepancy is women, compared to men, have more experience with discrimination on the basis of gender, therefore it is easier for them to recognize and interpret certain cues that symbolize sexism. Because of women’s previous experiences with sexism they may be less likely to endorse a sexist attitude. If a woman feels that a particular gender is being treated unfairly in a certain situation, they may be intolerant of attitudes and expanded rules of appropriate conduct that caters to that type of discriminatory behavior. Another possible explanation for the lack of significance achieved on our two scales (attitudes toward gender and society and the tolerance of a sexist event) can be explained by the previously mentioned research done by Ford. Recall that Ford’s findings suggest that only people high in hostile sexism were likely to be tolerant of a sexist event, and endorse sexist attitudes when exposed to sexist humor. In may very well be the case that our sample of 110 college students has very egalitarian attitudes toward genders, and strongly internalized attitudes about what is appropriate when making judgments about their feelings toward the genders. Unlike someone high in hostile sexism, a person with low hostility towards women, for instance, may use their internalized attitudes as a guide to navigate appropriateness in a given context. They do not need to understand the social context in order to protect themselves from repercussions of making an inappropriate comment, because the likelihood of such an event is improbable. A completely opposite, yet plausible explanation concerns participant effects, the participants in the study may have been unwilling to, or felt uncomfortable with exposing their sexist attitudes. It may very well be the case that participants were concerned about the social judgments they elicit by admitted to having sexist attitudes, despite the researchers attempts to quell these concerns by stressing anonymity. The Effects of Sexist Humor on Gender Attitudes 11 It is important to mention that in the instance of this study Glick and Fiske’s ASI and ATMS may have not elicited the desired effect because they were not properly used. Researchers like Ford, who have used these two scales, used the participants individual scores to assign them to condition, there by stratifying the sample based on endorsement of sexist attitudes. An explanation as to why these scales were not used in a similar manner in the present study is that one of the desired outcomes of this study was to determine whether or not the scales could be used as dependant measures. Obviously this was not the case in the present study; this may be because attitudes toward gender may be a static internalized attitude, not subject to manipulation by reading 7 paradigms in a laboratory setting. Further research in this area should take caution to pretest these scales, and use them appropriately. By assigning participants to condition on the basis of their scores, a study is in a better position to determine the affects humor has on sexist attitudes across genders. Other recommendations may be to use different variables in order to gain a better understanding of each participant’s view of women and men. Variables such as rape myth acceptance, and just world belief are good examples of variables that have been established in psychology and could be easily used to gain a more aggregate view of participant’s attitudes. The last and final recommendation to researchers interested in this area is to determine if the form of communication plays an important role in the manipulation. For instance, instead of having participants read paradigms or vignettes it would be interesting to determine if hearing the joke told by live person or a professional comedian has an affect on the attitudes of participants versus reading the paradigms. Also, how does the social influence of others in the room affect the humor rating of the paradigms? This would allow for more external validity, because rarely is it the case that one isolated person is experiencing a sexist joke. References Angelone, D.J., et al. 2005. The influence of peer interactions on sexually oriented joke telling. Sex Roles. 52. 187-199 Attardo, S. (1993). Violation of conversational maxims and cooperation: The case of jokes. Journal of Pragmatics. 19. 537-558. Bill, B. & Naus, P. (1992). The role of humor in the interpretation of sexist incidents. Sex Roles. 27. 645-664. Ford, Thomas E. (2000) Effects of sexist humor on tolerance of sexist events. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 26. 1094-1107. Ford, Thomas E. & Ferguson, Mark A. (2004) Social consequences of disparagement humor: a prejudiced norm theory. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 8. 7994. The Effects of Sexist Humor on Gender Attitudes 12 Glick, P. & Fiske, S.T. (1996) The ambivalent sexism inventory: differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 70. 491-512. Glick, P. & Fiske, S.T. (1999) The ambivalence toward men inventory: differentiating between hostile and benevolent beliefs about men. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 23. 519-536. Hobden, K.L. & Olsen, J.M. (1994). From jest to antipathy: Disparagement humor as a source of dissonance-motivated attitude change. Basic & Applied Social Psychology. 15. 239-249. Inman, Mary L. Baron, Robert S. Influence of prototypes on perceptions of prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996. 70. 727-739. Sev’er, A. & Ungar, S. (1997). No laughing matter: boundaries of gender-based humor in the classroom. Journal of Higher Education. 68. 87-105.