Shrader-Frechette, Kristin. Tainted: How Philosophy of Science Can

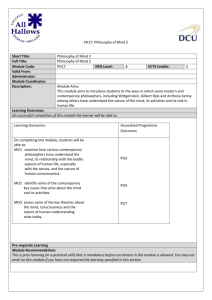

advertisement

Shrader-Frechette, Kristin. Tainted: How Philosophy of Science Can Expose Bad Science. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014. Can philosophy of science make a difference to science? Or is it as useful as ornithology is to birds, as the famous quip attributed to Richard Feynman goes? Kristin Shrader-Frechette has no patience for debating this question from first principles. Throughout her career she has demonstrated by example that philosophy of science can and should make a difference. And this is also the conceit of her latest book – to assemble together the many cases she studied over the past decades (most previously published) in which scientific controversies can be illuminated and indeed resolved by careful application of knowledge developed in traditional philosophy of science. But not just any controversies. Shrader-Frechette’s focus is squarely on what she calls ‘welfare-related science’ (6) – that is scientific research that bears directly on human and animal health and well-being, and most importantly bears on corporate profits. The safety of nuclear waste storage; the habitats of endangered animals; the health effects of pesticides and radiation are some of her examples. It is this combination of high economic and moral stakes that makes some scientific knowledge a valuable commodity whose content all too often benefits those who pay for this research. This is not a rare occurrence. As Shrader-Frechette repeatedly reminds, “at least in the United States, 75 percent of all science is funded by special interests in order to achieve specific practical goals” (2). When philosophers of science use their skills to redress the balance – that is, to evaluate the weight of evidence in a controversy blighted by asymmetries in power and money – they practice liberation science, of which this book is a primer and a manifesto. Shrader-Frechette argues for liberation science in two ways. First, each chapter puts forward a first-order claim evaluating a particular scientific controversy. All in all there are 14 such substantive claims spanning chapters 2 to 15 from across social, physical and biological sciences. The range is truly remarkable, from hydrogeology, to conservation ecology, economics, biochemistry, toxicology, statistics and nuclear physics. In each case, the presentation is accessible, requiring no background in either science or philosophy; but at the same time it is detailed and comprehensive enough to give prima facie support the author’s substantive verdicts. Thus, for instance, in chapter 3 Shrader-Frechette makes a strong case against the industry-funded toxicologist Edward Calabrese’s defense of hormesis (roughly, it refers to the alleged beneficial effect of toxins at low doses). Only time will tell whether her 14 verdicts will stand up to scrutiny, but the ball is squarely in the court of Shrader-Frechette’s critics. In many cases in question she is the first professional philosopher of science to engage in these controversies. (Kevin Elliot’s work on hormesis is one exception). So the mere existence of her 14 arguments in print is just as significant as their actual merits. Her strategy and hope is to show that these exercises are part of philosophy of science too. They are its proper applications so far wrongly neglected and underappreciated in the profession. The other side of her argument is second-order – to show the precise tools with which philosophy of science effects liberation. For starters logic and classic conceptual analysis, which are second nature to philosophers, often do the job. Thus chapters 2-4 uncover familiar logical fallacies in instances of scientific inference and expose lack of clarity about the boundaries of concepts. For example, in defending hormesis Calabrese shifts between different definitions of it in a way that protects hormesis from inconvenient evidence. Less convincingly, the author accuses Cass Sunstein’s defense of cost-benefit analysis of being logically inconsistent, an argument I found uncharitable. It is hardly news that logic and clarity can improve science, but Shrader-Frechette’s contribution is to show the power of these tools. The second and third role for philosophy of science is, respectively, with discovery and with justification of hypotheses. Discovery can be helped with judicious use of statistical data and thought experiments (chapters 5-8); while justification can be achieved by attending to theory’s favorable and unfavorable evidence, by conducting careful case studies and by inference to the best explanation (chapters 9-12). Again it is hard to disagree that indeed scientific practice presents instances in which each of these methods fails or succeeds. But Shrader-Frechette’s recurring theme is that these familiar tools look dramatically different when their use is scrutinized in practice rather than in idealized examples or cleaned up cases from history of science to which academic philosophers often help themselves. She observes time and again that methodological rules that look reasonable in the abstract – look for statistically significant results, favor the hypothesis best confirmed by evidence – can be dubious and harmful in the real world. If only statistically significant results are attended to, we miss out on important effects visible only in more narrowly defined populations or when causal mechanisms are complex. This rule becomes a convenient tactic for dismissing undesirable theoretical and mechanistic evidence, for example, evidence that points to harmful effects of various chemicals. Similarly, if we follow Larry Laudan in attending only to the comparative advantages of hypotheses rather than their truth or probability, it becomes all too easy to support hypothesis ‘nuclear power accidents do not cause cancer’ just because no evidence is collected that allows us to properly evaluate an alternative hypothesis. Absence of evidence, which is frequently, an intended outcome because evidence is expensive and troublesome to collect, is then easily converted into evidence of absence in the public sphere. When collection and analysis of data is carried out by scientists whose livelihoods stand or fall with the profits of their employers, it is no wonder that scientific evidence, produced in apparently legitimate ways, ends up lining up conveniently with those who foot the bill. The final set of second-order claims concerns the ability of philosophy of science to effect normative analysis of science. Chapters 13-15 intend to show that liberation science requires more than just logic, conceptual analysis and appropriate rules for discovery and justification. It also requires value judgments. In these chapters Shrader-Frechette uses moral and political arguments to argue a) in favor of maximin over expected utility maximization in some societal contexts, b) in favor of minimizing false negatives rather than false positives when stakes and uncertainty are high, and c) that scientists and philosophers of science have a duty to practice liberation science. The book closes with a shout-out to similarly-minded philosophers of science and practical suggestions about how to further liberation science in the public sphere through teaching, advocacy, activism and engagement with law. Does the overall case of the book succeed? Note that Shrader-Frechette adopts an expansive definition of philosophy of science, encompassing logic, conceptual analysis, decision theory and moral philosophy as well as the more traditional discussions about discovery, confirmation and explanation. It is hard to imagine even Feynman disagreeing that the first two – logic and clarity – are a good idea in science. On the latter three – the bread-and-butter topics of philosophy of science – some of Shrader-Frechette’s examples illustrate better how science can expose bad philosophy of science, rather than the other way around. After all it is the details of scientific practice, not philosophy of science primarily, which enable Shrader-Frechette to argue convincingly that Laudan was wrong about comparativism and that hypothetico-deductivists were wrong to dismiss case studies. Granted the line between philosophy of science and analysis of scientific practice is blurry if at all existent, but my point is that the grouping of so many radically different examples under one heading of ‘philosophy of science fixing science’ at times seems forced. But my main question concerns Shrader-Frechette’s proposal regarding values. The bringing of moral philosophy under the heading of philosophy of science is a more controversial though increasingly popular proposal. Philosophers of science from Philip Kitcher, to Helen Longino, Hugh Lacey and Heather Douglas to mention but a few, have all argued that good science requires good ethics and politics in a deeper way than traditionally recognized. Shrader-Frechette’s liberation science is also unabashedly value-laden – it invites us to identify the oppressed and the oppressors and help the former resist the latter. Stated as such liberation science might appear to follow the recent value turn in philosophy of science – indeed it is plausibly read as allowing the priority of justice over truth. But in fact none of the examples Schrader-Frechette discusses take us that far – she documents and exposes cases where economic interests got in the way of uncovering the full truth about phenomena of importance to welfare, but she does not discuss what happens when truth and justice collide. What to do, for instance, when truth is on the side of the oppressors? We are never told, and here lies the disadvantage of the example-based approach of this book. The rich examples illustrate liberation science without properly theorizing it. Liberation science speaks truth to power, but it is ambiguous whether the author is willing to go further and argue that scientific truths themselves may be subject to quality control by morality and politics. Today’s philosophy of science is not lacking in these latter more radical proposals: Kitcher is willing to claim that some research is off limits because of its power to hurt, Elizabeth Anderson and Alison Wylie have urged that feminist scientists are within their epistemic rights to fashion scientific concepts in line with their politics. I could not say where Shrader-Frechette’s liberation science falls on the spectrum of valueladenness. She is open to using value judgments to determine the relative importance of Type 1 versus Type 2 errors in Chapter 14. (This is very much in line with proposals by Douglas and others that epistemic standards should be sensitive to risks, which this chapter puzzlingly does not acknowledge). She is also open to redefining objectivity in a way that makes room for values. But she relies on intuitive notions of oppression, power and liberation, and on uncontroversial examples of bias in science, instead of offering a theory of which bias is legitimate and which isn’t. This approach would be perhaps understandable if no political philosophy of science existed and the intellectual territory was entirely uncharted, but that is no longer the case. Philosophy of science of today has embraced moral and political questions, or at least enough so, for it to be incumbent on anyone who proposes a project such as liberation science to develop this proposal properly and distinguish it from other comparable proposals. These reservations aside, today it is hard to find anyone who has done more to apply philosophy of science to correct injustice than Shrader-Frechette. This book gathers together the fruits of her admirable intellectual and practical efforts over several decades and gives these efforts a unifying narrative capable of inspiring other philosophers of science to use their skills where they are urgently needed. For that it deserves unreserved praise. Anna Alexandrova