Help for the Client and Veterinary Team

advertisement

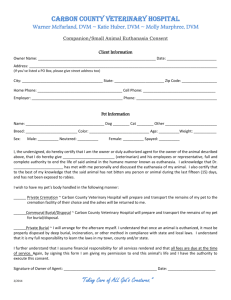

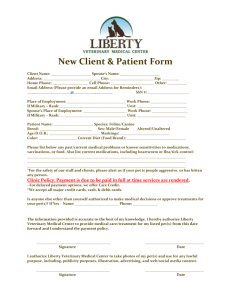

Companion Animal Euthanasia: Help for the Client and Veterinary Team Peter Foley, MSc, DVM, DACVIM Pet Loss and Grief Dealing with pet death and their owners’ grief can be very stressful for the veterinary team. Surprisingly, however, these can also be among the most fulfilling moments in your career, if you are able to deal with them in a healthy way, because you can be a real source of comfort and support to the client. Conversely, the stress generated by these encounters drive many animal health professionals from clinical practice. All clients experience grief when they are faced with a beloved pet’s death. Normal grief is defined as a normal emotional response to an external, consciously recognized loss. Grief is self-limited, and gradually subsides within a reasonable time. Grief can be anticipatory when knowledge of the impending death is foreseen. For example, the client begins grieving the moment a diagnosis of a fatal disease such as cancer is made – it does not start with the pet’s death. Different people may manifest grief differently, and their outward display of grief does not always reflect the depth of feeling they have inside. Sometimes grief is complicated, when more than the animal’s companionship is being lost. For example, the loss of a service dog can be particularly upsetting because not only is an animal friend being lost, but also the freedom that that partnership brought to the owner. Unresolved grief can be experienced when a current grieving episode triggers memories and feelings of another loss experienced in the past that was not fully dealt with. In rare instances, grief can be pathologic when the feelings that are experienced are so overwhelming that the client is profoundly depressed, and may even have suicidal or homicidal thoughts. While veterinary team members are not trained to treat unresolved or pathologic grief in their clients, they should be aware that these exist and should not hesitate to seek out help for the client from mental health services. Helping Clients Face the Decision to Euthanize In North America, few animals die directly of natural causes. Euthanasia is performed in the vast majority of cases to spare the animal the prolonged suffering and debilitation of a “natural” death. In many cases, the client and the veterinary team agree on when euthanasia is warranted. It can be very stressful if the client feels that euthanasia is not warranted, and the veterinary team does. Likewise it can be very stressful if the client wants to euthanize an animal that the veterinary team feels could be cured or at least given a chance. In cases where the veterinary team feels euthanasia is appropriate, but the client does not, one has to be very difficult that the client not be pressured into making a decision for euthanasia. In these situations, the client is seeking veterinary care in the hope that the animal can be cured. They have not understood or accepted how grim the prognosis is and how much the animal is suffering. If they have an optimistic outlook and they are confronted with a veterinarian who is pressuring them to euthanize, they now have to protect their pet from the veterinarian who is trying to kill it. This is obviously a dynamic the veterinary team wants avoid at all costs. If clients allow themselves to be convinced to euthanize their pets when they have not fully accepted that this is the best course of action, they will regret their decision, and for a long time afterwards they may be angry with themselves and their veterinary team because they “abandoned their pet in its hour of need.” The objective instead should be to help the client understand the disease process the animal is experiencing. In particular the client need to understand the animal’s comfort level (pain, respiratory distress, nausea, etc), and the prognosis for relieving any distress. Once the client fully understands the situation their pet is experiencing, the decision for euthanasia is usually made quite quickly. Sometimes the veterinarian and their staff may be tempted to judge the client for their reluctance to euthanize the pet: “He’s keeping the dog alive for his sake, not for the dog’s sake.” Be careful about judging clients in this situation. The very fact that the owner has taken the time to seek veterinary care, and is spending hard earned money proves that they are taking the situation very seriously. Be patient with clients as they struggle to understand and accept bad news. Often the information needs to be explained several times before the client can fully grasp the gravity of the animal’s situation. Concentrate on explaining the disease in layman’s terms, with particular emphasis on the animal’s comfort and prognosis. Avoid minimizing or “sugar-coating” the information. You do not need to be insensitive, but if the animal is suffocating from its lungs being full of fluid, then it is “in significant distress trying to breath” not “a little short of breath.” When Clients Want to Euthanize and the Veterinary Team Does Not In situations where the client wants to euthanize a pet, and the veterinary team is reluctant to do so, it is important to know what the policy of the clinic is. We need to have a service in our society that is able to destroy unwanted animals, otherwise owners will be obliged to abandon or attempt to destroy the animals on their own. In some communities, it is an animal shelter or animal control authority that performs this function. In others, it is the veterinary team. In other practices, the policy is to perform euthanasia only on animals with significant disease. Some practices leave the decision up to the veterinarian. Be careful not to pass judgment on owners who are presenting pets for euthanasia for apparently minor reasons. On the outside, they may appear to be nonchalant about it. Realize, however, that few people take such decisions lightly, and that it probably took a lot of courage to bring the pet to the veterinary clinic and face being judged by the most animal-loving people in the community. Realize as well that people in this situation often see themselves as having few options to solve the problem. Client-Present Euthanasia Not so very long ago, it was considered very unusual for a client to be present at the euthanasia of their pet. Now, the situation is reversed, and it rare for a client not to be present. Having the client present for the euthanasia adds challenges, but often helps to bring closure to owners struggling with the death of their pet. For many owners, it is important to comfort the animal at the end, so it does not die anxiously in the presence of strangers. When planning a client-present euthanasia, it is important to choose a time of day when you are unlikely to be interrupted by other emergencies. For some practices that is first thing in the morning; for others at the end of the day; and for still others a euthanasia in the client’s home. When the client arrives at the clinic, they should be taken to a private area so they do not need to wait in the waiting room with other clients. The room where the euthanasia is to be performed should be large enough to be comfortable for all the people present – usually a minimum of four people (the client and friend, the veterinarian, and one staff member to assist). There should be enough chairs for everyone to sit, and the floor or table should be made comfortable for the animal with blankets or pillows. Regardless of the time and setting, it is best to determine details of paperwork, payment, and disposal of the body prior to the euthanasia procedure. A consent form should be signed by the client indicating ownership, the identity of the animal, the request that euthanasia be performed, and the plan for disposal of the body (owner leaving with the body, clinic disposal, cremation, post-mortem examination, etc). Even if the client has been present for the euthanasia of a pet in the past, they should be prepared for what they will see. This should include an explanation of how the drugs work, pointing out that it is an overdose of an anesthetic medication, that the drug is painless, and that because it is an overdose, it not only anesthetizes the animal and makes it fall asleep, it also anesthetizes the heart and lungs after the animal falls asleep. The animal is not aware of its heart of lungs ceasing to function. There are some things the client may witness that may be disturbing if they are not prepared for them. In particular, the some animals may feel dizzy or disoriented as the anesthetic first takes effect. This may cause them to bark or meow for a few seconds just before they fall asleep. I explain that this is not a sign of pain, but rather of surprise, and is common in all animals just as the anesthetics begin to take effect. I find this vocalization is more common in healthier animals, and it seems to happen less commonly if rapid acting anesthetic agents like thiopental, propofol, or alfaxalone are used before the pentobarbital euthanasia solution. Owners should be cautioned that the eyes of dogs and cats tend to remain open after death. They should also be aware that as the body relaxes, the animal may urinate or defecate, so we put absorbent pads under the animal for this purpose. I caution the owners that they may see some reflex muscle contractions after death. In particular, I tell them that the muscle that controls breathing, the diaphragm, can contract after death – sometimes, even minutes after the animal has stopped breathing. The animal can sigh unexpectedly when this happens. If clients are not prepared for this, it can be shocking, as they worry that the animal is somehow reviving itself. Once I take the client to the room where the procedure will be performed, I ask them if they are ready for me to take the pet around back to place an intravenous catheter. Either the cephalic veins in the front legs or the saphenous veins in the hind legs can be used. Frequently, I prefer the hind leg veins as they allow the owner to be closer to the animal’s head as I am euthanizing the animal. Once the catheter has been placed, I bring the animal back to the owner and again offer them time to spend alone with the pet. When everyone is ready, I have my assistant gently hold the pet’s leg so the pet does not withdraw it suddenly as I inject the euthanasia solution. Death happens within seconds. I listen to the heart for any signs of life, and clearly let the owner know that the pet has died (“He’s gone”, or “He is dead”). Clients are frequently surprised by how rapidly the death occurs, so they need to be informed that it is over. Often clients want to talk about their pet at that time, and I give them as much time as they need. I always offer them time alone with the body if they want, and sometimes they take me up on that offer. If you leave the client alone with the body, be sure to tell them when you will check back with them (usually 10 minutes), so they can prepare and compose themselves before you return. When the time comes to escort the owner from the room, I leave the animal in the care of my assistant, so that the last look that the client has of their pet is with someone who is carefully tending to the body. It can be disturbing to the owner to have them see the body left alone and unattended in the room as they leave. Likewise, do not place the body in a plastic garbage bag in front of the owner, and always handle the body gently as if the animal were still alive and just asleep. Seeing the body being jostled or improperly supported can be distressing to the owner. We routinely make paw prints in quick drying modeling clay that can be purchased from most craft stores. Clients often appreciate keepsakes like paw prints, locks of hair, collars, and leashes. We also routinely send condolence cards signed by everyone who has cared for the animal. There are condolence cards that are specifically designed for pet death, but my own personal preference is blank cards with nature scenes, landscapes, or flowers, and I write the message myself inside. With clients who are particularly isolated in the community, or who have had a particularly hard time with the death of their pet, we usually give a follow-up call in the next day or two, sometimes accompanied by flowers. Some clients want to memorialize their pets in some way. Often that takes the form of making a contribution to some fund to help other animals: a donation to the local animal shelter, a donation to a research fund that investigates particular diseases in animals, a fund that provides care to pets of clients with limited finances, etc. Clients often sympathize with me, and say that euthanasia must be one of the hardest things about my job. I agree that it is not easy, but at the same token I feel very humbled and privileged to help people through this very difficult time. I am seeing people at their most vulnerable, but also at their most courageous, noble, and loving. That is a true honor to serve people at that time in their lives.