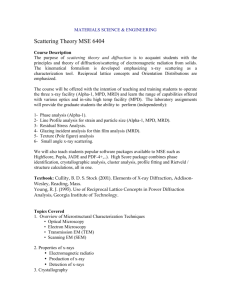

Table of Contents

advertisement

Phase Identification by X-ray diffraction Group 3 Amir Keyvan Edalat Nobarzad Mahdi Masoumi Khalilabad Keivan Heirdari SYS862/Autumn 2014 Prof. Mohammad Jahazi Table of Contents 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 3 2 Generation of X-ray ......................................................................................................... 3 3 Bragg`s Law ..................................................................................................................... 6 4 Diffraction Intensity ......................................................................................................... 7 5 Structure factor ................................................................................................................. 8 6 X-ray Diffractometry........................................................................................................ 9 6.1 Instrumentation ....................................................................................................... 10 6.2 System Aberrations ................................................................................................. 12 7 Samples and Data Acquisition ....................................................................................... 13 7.1 Sample Preparation ................................................................................................. 13 7.2 Acquisition and Treatment of Diffraction Data ...................................................... 14 8 Distortions of Diffraction Spectra .................................................................................. 14 8.1 Preferential Orientation ........................................................................................... 14 8.2 Crystallite Size ........................................................................................................ 15 8.3 Residual Stress ........................................................................................................ 15 9 Application ..................................................................................................................... 16 9.1 Phase Identiication .................................................................................................. 16 9.2 Quantitative Measurement ...................................................................................... 17 10 Wide-Angle X-Ray Diffraction and Scattering .......................................................... 17 11 Refrences .................................................................................................................... 18 1 Introduction X-ray diffraction (XRD analysis or XRPD analysis) is very useful to identify the phases in powder specimens, poly crystalline aggregate solids and thin-film samples. The key for identifying of materials by this method is their unique crystalline structure. XRD has wide variety applications such as: Detecting crystalline minority phases (at concentrations greater than ~1%) Determining crystallite size for polycrystalline films and materials Determining percentage of material in crystalline form versus amorphous Measuring sub-milligram loose powder or dried solution samples for phase identification Analyzing films as thin as 50 angstroms for texture and phase behaviors Determining strain and composition in epitaxial thin films Determining surface offcut in single crystal materials Measuring residual stress in bulk metals and ceramics 2 Generation of X-ray X-rays are short wavelength and high energy waves of electromagnetic radiation which are characterized either by wavelength or photon energy. Most X-rays have a wavelength in the range of 0.01 to 10 nanometers; X-ray wavelengths are shorter than those of UV rays and typically longer than those of gamma rays. Figure 2-1. The electromagnetic spectrum, presented as a function of wavelength, frequency, and energy. X-rays and γ-rays comprise the high-energy portion of the electromagnetic spectrum[1] X-rays are produced by high speed electrons accelerated by a high voltage filled colliding with a metal target. rapid deceleration of electrons on target enables the kinetic energy of electrons to be converted to energy of X-ray radiation, the wavelength of x-ray radiation, λ, is related to the acceleration voltage of electrons(V)as shown in the following equation [2]: 𝜆= 1.2398 ∗ 103 (𝑛𝑚) 𝑉 Eq. 2-1 Figure 2-2. X-ray tube schematic[2]. Figure 2-2 indicates an X-ray tube containing a source of electrons and two metal electrodes in a vacuum tube, the high voltage maintained across these electrodes rapidly draws the electrons to the anode (target) there are windows to guide X-rays out of the tube. Extensive cooling is necessary for the X-ray tube because most of the kinetic energy of electrons is converted into heat; less than one percent is transformed into X-rays. As we can see in equation more voltage we have we will produce an X-ray with shorter wavelength which has maximum radiation energy. For XRD we need we need a single wave Xray radiation which is generated by filtering out other radiations from the spectrum. Figure 2-3 indicates the phenomenon of X-ray generation. Figure 2-3. electronic transition in an atom (schematic), emission processes indicated by arrows [3]. In this phenomenon an incident electron with enough energy excites an electron in inner shell of an atom (our target) to a higher state; another electron from outer shell will be replaced instead of excited electron. The energy released by this action is in form of X-ray. The wavelengths can be different depending that the electron in replace to which layers, these lines are called characteristics lines, for example if we have molybdenum as target metal, the K lines have a wavelength of 0.7A, L lines about 5A, and M lines still higher, usually only K lines are used for X-ray diffraction because the longer wavelengths are being too easily absorbed. As shown in Figure 2-3 K layer can be filled by an electron from L or M layer, the waves produced are named Kα and Kβ respectively. Intensity of Kα is higher than Kβ because the probability of filling an electron from L to K is more than M to K. Table 2-1 shows the X-ray characteristics of usual target materials. If the heavier metal that we always use is Mo, because the metals with high density are not appropriate for target. Table 2-1. X-ray characteristics of usual target materials[2]. Many X-ray diffraction experiments need radiation which is as closely monochromatic as possible to We need to also filter the rays in order to keep only Kα, to do this filters made of some materials which can absorb all other rays except Kα.Table 2-2 indicates the appropriate filters for each target. Table 2-2. Filters for suppression of Kβ radiations[3]. Before explaining the Braggs law, let’s make a quick review on phenomenon of wave interferences, as indicated in Figure 2-4 Constructive interference occurs when combining two same-wavelength waves that do not have a phase difference between them. However, completely destructive interference occurs when combining two waves with phase difference of a half wavelength (λ/2). In fact When they have a phase difference of nλ (n is an integer), called ‘in phase’, constructive interference occurs. When they have a phase difference of nλ/2, called ‘completely out of phase’, completely destructive interference occurs. Figure 2-4. Constructive(upper figure) and destructive interface[2]. 3 Bragg`s Law The interpretation of XRD is based on Brag law which determines the scattering angles at which peaks of strong scattered intensity may occur, composition is measured through identification of positions and intensities of diffraction peaks which are unique to a given chemical compound. When an X-Ray beam with a known wavelength is incident to a crystalline solid, the crystalline planes will make the diffraction, according to Bragg`s Law the deflected waves will not be in phase except when the following relationship is satisfied: 𝑛𝜆 = 2𝑑 sin 𝜃 Eq. 3-1 The Eq. 3-1 is the Bragg`s law, with this equation when we have constructive interface we can determine the distance between atomic planes and therefore we can determine the crystalline structure of material. Figure 3-1.Brags law [2]. Bragg's law, as stated above, can be used to obtain the lattice spacing of a particular cubic system through the following relation: 𝑑= 𝑎 √ℎ2 𝑘2 Eq. 3-2 𝑙2 + + Where a is the lattice spacing of the cubic crystal, and h, k, and l are the Miller indices of the Bragg plane. Combining this relation with Bragg's law: (sin 𝜃)2 𝜆 2 ( ) = 2 2𝑎 ℎ + 𝑘 2 + 𝑙2 Eq. 3-3 One can derive selection rules for the Miller indices for different cubic Bravais lattices; here, selection rules for several will be given as is. 4 Diffraction Intensity Even if we satisfy the Bragg`s law we cannot make sure that we can detect diffraction from crystallographic planes. We need also appropriate diffraction intensity. Diffraction intensity may vary among planes even though the Bragg conditions are satisfied. X-ray diffraction by a crystal arises from X-ray scattering by individual atoms in the crystal. The diffraction intensity relies on collective scattering by all the atoms in the crystal. In an atom, the X-ray is scattered by electrons, not nuclei of atom. An electron scatters the incident X-ray beam to all directions in space. The scattering intensity is a function of the angle between the incident beam and scattering direction (2θ). The X-ray intensity of electron scattering can be calculated by the following equation. 𝐼0 1 + (cos 2𝜃)2 𝐼(2𝜃) = 2 𝐾 𝑟 2 Eq. 4-1 Io is the intensity of the incident beam, r is the distance from the electron to the detector and K is a constant related to atom properties. The last term in the equation shows the angular effect on intensity, called the polarization factor. The incident X-ray is unpolarised, but the scattering process polarizes it. The total scattering intensity of an atom at a certain scattering angle, however, is less than the simple sum of intensities of all electrons in the atom. There is destructive interference between electrons due to their location differences around a nucleus, as illustrated in Figure 4-1. Destructive interference that results from the path difference between X-ray beams scattered by electrons in different locations is illustrated in Figure 3-1. Figure 3-1-b shows an example of a copper atom, which has 29 electrons. The intensity from a Cu atom does not equal 29 times that of a single electron in Equation 2.9 when the scattering angle is not zero. The atomic scattering factor (f) is used to quantify the scattering intensity of an atom. 𝑎𝑚𝑝𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑢𝑑𝑒 𝑜𝑓 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑤𝑎𝑣𝑒 𝑠𝑐𝑎𝑡𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑒𝑑 𝑏𝑦 𝑜𝑛𝑒 𝑎𝑡𝑜𝑚 Eq. 4-2 𝑚𝑝𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑢𝑑𝑒 𝑜𝑓 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑤𝑎𝑣𝑒 𝑠𝑐𝑎𝑡𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑒𝑑 𝑏𝑦 𝑜𝑛𝑒 𝑒𝑙𝑒𝑐𝑡𝑟𝑜𝑛 The atomic scattering factor is a function of scattering direction and X-ray wavelength as shown in Figure 3-1-b for copper atom. The scattering intensity of an atom is significantly reduced with increasing 2θ when the X-ray wavelength is fixed. 𝑓= Figure 4-1. (a) Scattering of an X-ray by electrons in an atom and (b) the intensity of a scattered beam represented by the atomic scattering factor (f), which is a function of scattering angle (θ) with the maximum value at 0◦. The maximum is equal to the number of electrons in the atom[2]. 5 Structure factor Structure Extinction refers to interference between scattering atoms in a unit cell of a crystal if there is more than one atom in a unit cell. The resultant of the waves scattered by all the atoms in the unit cell, in the direction of the h, k and l reflection, is called the structure factor (Fhkl). The structure factor depends on both the position of each atom and its scattering factor. For j atoms in a unit cell, 𝐹ℎ𝑘𝑙 = ∑ 𝑓𝑗 𝑒 2𝜋𝑖(ℎ𝑥𝑗+𝑘𝑦𝑗+𝑙𝑧𝑗) 𝑗 Eq. 5-1 Where fj is the scattering factor of the jth atom and xj, yj, and zj are its fractional coordinates. This series can be expressed in terms of sines and cosines (periodic nature of a wave) and is called a Fourier series. In a crystal with a center of symmetry and n unique atoms in the unit cell (the unique set of atoms is known as the asymmetric unit): For example, a body-centered cubic (BCC) united cell has two atoms located at [0,0,0] and [0.5, 0.5, 0.5].We can calculate the diffraction intensity of (001) and (002) using Equation 2.11. 𝐹001 = 𝑓𝑒𝑥𝑝[2𝜋𝑖(0 + 0 + 1) + 𝑓𝑒 2𝜋𝑖(0∗0.5+0∗0.5+1+0.5) ] = 𝑓 + 𝑓𝑒 𝜋𝑖 = 0 𝐹002 = 𝑓𝑒𝑥𝑝[2𝜋𝑖(0 + 0 + 2 ∗ 0) + 𝑓𝑒 2𝜋𝑖(0∗0.5+0∗0.5+2∗0.5) ] = 𝑓 + 𝑓𝑒 2𝜋𝑖 = 2𝑓 This structure factor calculation confirms the geometric argument of (001) extinction in a Body-centered crystal. Practically, we do not have to calculate the structure extinction using Eq. 5-1 for simple crystal structures such as BCC and face-centered cubic (FCC). Their structure extinction rules are given in Table 2.2, which tells us the detectable crystallographic planes for BCC and FCC crystals. From the lowest Miller indices, the planes are given as following. BCC (1 1 0), (2 0 0), (2 1 1), (2 2 0), (3 1 0), (2 2 2), (3 2 1), …. FCC (1 1 1), (2 0 0), (2 2 0), (3 1 1), (2 2 2), (3 3 1), .... A unit cell with more than one type of atom, the calculation based on Eq. 5-1 will be more complicated because the atomic scattering factor varies with atom type. We need to know the exact values of f for each type of atom in order to calculate F. Often, reduction of diffraction intensity for certain planes, but not total extinction, is seen in crystals containing different types of atoms. 𝐹ℎ𝑘𝑙 = 2 ∑ 𝑓𝑗 cos 2𝜋(ℎ𝑥𝑛 + 𝑘𝑦𝑛 + 𝑙𝑧𝑛 ) Eq. 5-2 𝑗 6 X-ray Diffractometry The XRD instrument is called an X-ray diffractometer. Single wave length incidents to the specimen surface and detector measure the intensity of the diffracted beam. The beam incident angle changes continuously thus a spectrum of diffraction intensity versus the angle between incident and diffraction beam is produced. This spectrum is compared with database containing over 60,000 diffraction spectra of known crystalline substances 6.1 Instrumentation Diffractometer functions are the x-ray diffraction detecting from material and the measuring of diffraction intensity. Figure 6-1 shows a real picture of a powder X-ray diffractometer. Figure 6-2 demonstrates the geometrical arrangement of X-ray source, specimen and detector. The Xray radiation generated by an X-ray tube passes through special slits which collimate the X-ray beam. These Soller slits are commonly used in the diffractometer. They are made from a set of closely spaced thin metal plates parallel to plane of Figure 6-2 to prevent beam divergence in the director perpendicular to the figure plane. A divergent X-ray beam passing through the slits strikes the specimen (Figure 6-3). X-rays are diffracted by the specimen and form a convergent beam at receiving slits before they enter a detector. The diffracted X-ray beam needs to pass through a monochromatic filter (or a monochromator) before being received by a detector. Relative movements among the X-ray tube, specimen and the detector ensure the recording of diffraction intensity in a range of 2θ. Note that the θ angle is not the angle between the incident beam and specimen surface; rather it is the angle between the incident beam and the crystallographic plane that generates diffraction. Diffractometers can have various types of geometric arrangements to enable collection of X-ray data. The majority of commercially available diffractometers use the Bragg–Brentano arrangement, in which the X-ray incident beam is fixed, but a sample stage rotates around the axis perpendicular to the figure plane of Figure 6-2 in order to change the incident angle. The detector also rotates around the axis perpendicular to the plane of the figure but its angular speed is twice that of the sample stage in order to maintain the angular correlation of θ–2θ between the sample and detector rotation. The Bragg–Brentano arrangement, however, is not suitable for thin samples such as thin films and coating layers. The technique of thin film X-ray diffractometry uses a special optical arrangement for detecting the crystal structure of thin films and coatings on a substrate. The incident beam is directed to the specimen at a small glancing angle (usually <1◦) and the glancing angle is fixed during operation and only the detector rotates to obtain the diffraction signals as illustrated in Figure 6-4. Thin film X-ray diffractometry requires a parallel incident beam, not a divergent beam as in regular diffractometry. Also, a monochromator is placed in the optical path between the X-ray tube and the specimen, not between the specimen and the detector. The small glancing angle of the incident beam ensures that sufficient diffraction signals come from a thin film or a coating layer instead of the substrate[2]. Figure 6-1. Image of a powder X-ray diffractometer. The incident beam enters from the tube on the left, and the detector is housed in the black box on the right side of the machine. This particular XRD machine is capable of handling six samples at once, and is fully automated from sample to sample[4]. Figure 6-2. diffractometer[2]. Geometric arrangement of X-ray Figure 6-3. Soller slit position [5] Figure 6-4. Optical arrangement for thin film diffractometry[2]. 6.2 System Aberrations The ideal and experiment situations are not completely same in other words there are errors in experiments. XRD data are sensitive to as many as 35 different factors. These factors can be grouped in to three general sources of "error". Instrument sensitive Sample sensitive Specimen sensitive The experimental d value is not exactly same with d theoretical value[6]: Theoretical d-value (nλ = 2d sinθ) Practical d-value (theoretical + inherent aberrations) Experimental d-value (practical + inherent sample aberrations + errors) Errors due to parafocusing always exists. The errors of parafocusing are referred: Axial divergence error; Flat-specimen error; and Specimen transparency error. Focusing circles for various geometries is shown in Figure 6-5.The incident X-ray beam has a certain degree of divergence; part of the specimen surface is not located on the focusing circle and the atomic planes inside the specimen are not located on the focusing circle. These aforementioned conditions generate system errors which affect the peak positions and widths in the diffraction spectrum[2]. Figure 6-5. Focusing circles for various geometries in Bragg–Brentano arrangement[6] 7 Samples and Data Acquisition 7.1 Sample Preparation The X-ray diffractometer was originally designed for examining powder samples. However, the diffractometer is often used for examining samples of crystalline aggregates other than powder. Polycrystalline solid samples and even liquids can be examined. Importantly, a sample should contain a large number of tiny crystals (or grains) which randomly orient in threedimensional space because standard X-ray diffraction data are obtained from powder samples of perfectly random orientation. Relative intensities among diffraction peaks of a non-powder sample can be different from the standard because perfect randomness of grain orientation in solid samples is rare. The best sample preparation methods are those that allow analysts to obtain the desired information with the least amount of treatment because chemical contamination may occur during the sample treatments[2]. The most commonly used approach to reduce particle size is to grind the substance using a mortar and pestle, but mechanical mills also do a fine job (Figure 7-1). Both the former and the latter are available in a variety of sizes and materials. Mortars and pestles are usually made from agate or ceramics. Agate is typically used to grind hard materials (e.g., minerals or metallic alloys), while ceramic equipment is suitable to grind soft inorganic and molecular compounds. Mechanical mills require vials and balls, which are usually made from hardened steel, tungsten carbide, or agate[7]. Figure 7-1. The tools most commonly used in sample preparation for powder diffraction experiments: agate mortar and pestle (left), and ball-mill vials made from hardened steel (middle) and agate (right). 7.2 Acquisition and Treatment of Diffraction Data A diffractometer records diffraction intensity versus 2θ angle. A number of intensity peaks located at different 2θ provide a ‘fingerprint’ for a crystalline solid such as Fe2O3. Each peak represents diffraction from a certain crystallographic plane. Matching an obtained peak spectrum with a standard spectrum enables us to identify the crystalline substances in a specimen. Spectrum matching is determined by the positions of the diffraction peak maxima and the relative peak intensities among diffraction peaks. For example Figure 7-2 shows comparing between a standard reference pattern [8] for Fe2O3 and result of an experiment [9]. To obtain adequate and data of sufficient quality for identifying a material, the following factors are important: Choice of 2θ range Choice of X-ray radiation Choice of step width for scanning To obtain a satisfactory diffraction spectrum, the following treatments of diffraction data treatment should be done: Smooth the spectrum curve and subtracting the spectrum background; Locate peak positions; and Strip Kα2 from the spectrum, particularly for peaks in the mid-value range of 2θ[2]. a b Figure 7-2. comparing between a standard reference pattern and result of an experiment a) standard refrence pattern[8], b) result of an experiment[9]. 8 Distortions of Diffraction Spectra 8.1 Preferential Orientation It is supposed to match both peak locations and relative peak intensities between the acquired spectrum and the standard if the sample is the same substance as the standard. However, it is not always possible to match relative intensities even when the examined specimen has the same crystalline structure as the standard. One reason for this discrepancy might be the existence of preferential crystal orientation in the sample. This often happens when we examine coarse powder or non-powder samples. Preferential orientation of crystals (grains in solid) may even make certain peaks invisible. Figure 8-1. Change of peak line width with crystal size[10]. Figure 8-2. X-ray diffraction of nano-SiC synthesized for TMS at 1573K andBragg reflex positions according to the β-SiC Phase[11]. 8.2 Crystallite Size Ideally, a Bragg diffraction peak is a line without width, as shown in Figure 7-2-a. In reality, diffraction from a crystal specimen produces a peak with a certain width, as shown in Figure 7-2b. The peak width can result from instrumental factors and the size effect of the crystals. Small crystals cause the peak to be widened due to incompletely destructive interference. The crystalline phases of the silicon carbide powders were identified by X-ray powder diffraction with a Siemens D5000 diffractometer using a CuKα source (Figure 8-2). The crystallite or grain size, dXRD, can be calculated from the XRD line broadening using Scherrer's formula: 𝑑 𝑋𝑅𝐷 = 𝐾. 𝜆 𝛽. 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝜃 Where K is a shape constant (here assumed as 1), A. is the wavelength of the X-rays (0.154 nm for Cu-Ka), β is the difference of the width (full width at half maxi-mum. b) of the (220) peak at 2θ= 59.9 of the ultrafine powders and of a standard microcrystalline β-SiC powder (bs Aldrich, 99.9%): β=b-bs 8.3 Residual Stress Any factor that changes the lattice parameters of crystalline specimens can also distort their X-ray diffraction spectra. For example, residual stress in solid specimens may shift the diffraction peak position in a spectrum. Residual stress generates strain in crystalline materials by stretching or compressing bonds between atoms. Thus, the spacing of crystallographic planes changes due to residual stress[2]. Figure 8-3 shows Peak Shift in an alloy 625 C-Ring Due to residual stress[12]. The strain 𝜀𝑧 can be measured experimental by measuring the peak position 2θ, and Bragg equation for a value of dn. If we know the unstrained inter-planar spacing d0 then[13]; 𝜀𝑧 = 𝑑𝑛 − 𝑑0 𝑑0 Figure 8-3. Peak Shift in an alloy 625 C-Ring Due to residual stress[12]. 9 Application 9.1 Phase Identiication Identification of crystalline substance and crystalline phases in a specimen is achieved by comparing the specimen diffraction spectrum with spectra of known crystalline substances. Xray diffraction data from a known substance are recorded as a powder diffraction file (PDF). Most PDFs are obtained with CuKα radiation (example Figure 9-1). Standard diffraction data have been published by the ICDD, and they are updated and expanded from time to time. When we need to identify the crystal structure of a specimen that cannot be prepared as powder, matches of peak positions and relative intensities might be less than perfect. In this case, other information about the specimen such as chemical composition should be used to make a judgment [2]. Figure 9-1. The Indexed PDF card NiMnO3 [7]. 9.2 Quantitative Measurement The intensity of the diffraction peaks of a particular crystalline phase in a phase mixture depends on the weight fraction of the particular phase in the mixture. Thus, we may obtain weight fraction information by measuring the intensities of peaks assigned to a particular phase.Generally, we may express the relationship as the following 𝐼𝑖 = 𝐾𝐶𝑖 𝜇𝑚 Where the peak intensity of phase i in a mixture is proportional to the phase weight fraction (Ci), and inversely proportional to the linear absorption coefficient of the mixture (μm). K is a constant related to the experimental conditions including wavelength, incident angle, and the incident intensity of the X-ray beam. 10 Wide-Angle X-Ray Diffraction and Scattering Wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD) or wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) is the technique that is commonly used to characterize crystalline structures of polymers and fibers. The technique uses monochromatic X-ray radiation to generate a transmission diffraction pattern of a specimen that does strongly absorb X-rays, such as an organic or inorganic specimen containing light elements. WAXD or scattering refers to X-ray diffraction with a diffraction angle 2θ >5◦, distinguishing it from the technique of small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) with 2θ <5◦[2].Nanoparticles are essential building blocks to make many new materials with tailored optical, magnetic, mechanical, and electrical properties. Examples include new magnetic recording media, sensors, and catalyst supports. Such particles are often anisotropic in shape and resemble disks, rods, or ellipsoids. Scientific interest in nanometre-sized particles focuses on their size-dependent physical properties that include specific surface area, quantum confinement, and super paramagnetism. Characterization of both shape and size of such particles is important in the development of these materials and as a means to control the quality of the synthesis. Wide-angle X-ray diffraction with conventional laboratory equipment can be used as a tool for this characterization[14]. 11 Refrences 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. Seibert, J.A., X-Ray Imaging Physics for Nuclear Medicine Technologists. Part 1: Basic Principles of X-Ray Production. Journal of Nuclear Medicine Technology, 2004. 32(3): p. 139-147. Leng, Y., Materials Characterization: Introduction to Microscopic and Spectroscopic Methods. 2013: Wiley. Cullity, B.D., Elements of X Ray Diffraction. 2011: BiblioBazaar. Barron, A., Physical Methods in Chemistry and Nano Science August 7, 2012: Connexions, Rice University. Bargar, J. Guide to XAFS Measurements at SSRL 07 DEC 2004; Available from: http://wwwssrl.slac.stanford.edu/mes/xafs/index.html. Schroeder, P. Factors that affect d's and I's. 2014; Available from: http://clay.uga.edu/courses/8550/XRD.html. Pecharsky, V.K. and P.Y. Zavalij, Fundamentals of Powder Diffraction and Structural Characterization of Materials. 2009: Springer US. Bernal, D., D.R. Dasgupta, and A.L. Mackay, The Oxides and Hydroxides of Iron and Their Structural Inter-Relationships. Clay Minerals, 1959. 4: p. 15. Augustyn, C.L., et al., One-Vessel synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles prepared in non-polar solvent. RSC Advances, 2014. 4(10): p. 5228-5235. Committee, A.S.M.I.H., ASM Handbook, Volume 06 - Welding, Brazing, and Soldering. ASM International. Winterer, M., Nanocrystalline Ceramics: Synthesis and Structure. 2002: Springer. Berman, R.M. and I. Cohen, Method for improve x-ray diffraction determinations of residual stress in nickel-base alloys. 1990, Google Patents. Fitzpatrick, E. and N.P. Laboratory, Determination of Residual Stresses by X-ray Diffraction. 2005: National Physical Laboratory. Qazi, S.J.S., et al., Use of wide-angle X-ray diffraction to measure shape and size of dispersed colloidal particles. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 2009. 338(1): p. 105-110.