- University of Portsmouth

advertisement

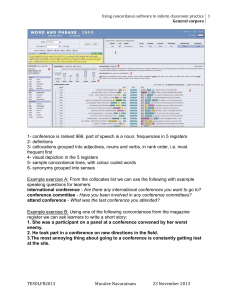

This is the author’s postprint. Copyright is now held by Edinburgh University press. Final version is available at http://www.euppublishing.com/doi/abs/10.3366/cor.2014.0049. A, an and the environments in Spoken Korean English Glenn Hadikin School of Languages and Area Studies University of Portsmouth Park Building King Henry 1 Street Portsmouth PO1 2DZ Glenn.hadikin@port.ac.uk This paper comprises an analysis of small corpora of spoken Korean English: a burgeoning New English that is rarely discussed in published articles. With a theoretical framework based on Hoey’s Theory of Lexical Priming (Hoey 2005) the lexical environment surrounding the items a, an and the in two Korean corpora (one comprising Korean English speakers in Liverpool, England and the other, speakers in Seoul, Korea) are compared with two British comparator corpora. The results show a balance of differences and similarities between the Korean corpora which may suggest that while Korean English is distinct from British varieties recent priming effects and the L1 are interacting in complex ways that give each corpus a unique identity. 1 Introduction The Republic of Korea, or South Korea, is a small country situated between China and Japan and has a population of just fewer than 50 million1. The people speak Korean, considered to 1 Population data taken from http://www.worldatlas.com/aatlas/populations/ctypopls.htm on 24/3/12 1 be either an isolated language or part of the Altaic group that includes Turkic and Japonic languages (Lee and Ramsey 2000), and, as Porter (2011) reports, ‘English mania’ has now become so widespread that people have even had surgery on their tongue in the hope that it will improve pronunciation. The search term “English in Korea” gets notably more hits on Google than the term “English in China” (1.6 million and 618 000 respectively2); English has been taught to all middle and high school students since 1945 and in all elementary schools since 1997 (Tollefson 2002) but until very recently it was rarely listed as a World English in reference books such as Crystal (2003:111). Crystal reproduces a ‘circle of World Englishes’ from McArthur (1987) that includes 51 regional varieties including Appalachian and Inuit English as well as Chinese and Japanese English but it does not mention the English used in South Korea whatsoever (in this paper the terms Korea and South Korea are both used to refer to the Korean republic). The large number of teaching positions being advertised online at the time of writing, however, is a reflection of the level of interest in English3 and the extent to which it is used in Korea in the 21st century is a reflection of Korea’s developing multiculturalism (Mehlsen 2011 provides a useful summary) where English is used more and more outside of the classroom albeit typically in groups where at least one speaker does not speak Korean. Korean English has more recently been discussed as part of a World Englishes model (see Kachru and Nelson 2006) and the variety will be discussed in this light throughout this paper i.e. although Korean speakers often refer to external norms it is a developing form of English in its own right and its unique features can be described and discussed without necessarily being seen as erroneous. This is in contrast to discussions of Konglish (a disparaging term used to describe a mixture of Korean and English). Korean Learner English, comprising the features described in Lee (2001), is a more positive construct that highlights certain cases where the L1 affects Korean people’s English, and is noted to still carry the implicit message that features of English unique to Korea or East Asia are problematic. Previous Korean English studies have tended to focus on pronunciation (see Yeni-Komshian, Flege and Liu 2000 for example) or ideological and pedagogical issues of teaching English such as Park’s (2009) study which claims three underlying ideologies in Korean English: necessitation is the 2 Google searches conducted on 24/3/12 3 See travelandteachrecruiting.com and teachkoreans.com as examples 2 idea that English is a necessary tool for success in a global economy, externalisation suggests that English is often still seen as the language of the other and can conflict with a Korean identity and, finally, a shared ideology of self-depreciation – that no matter what they do Koreans see themselves as poor at English (Park 2009). A study that explicitly argues that Korea now has a form of codified English that is taught in schools is Shim (1999). Shim highlights a variety of usages that are found in Korean English textbooks ranging from lexico-semantic differences (on life used as a synonym for alive e.g. gardens come on life again) to grammatical differences such as her claim that the simple present tense is not differentiated from the progressive form; as an example Shim reports that the following exchange would be acceptable in codified Korean English: Q What happens to the grass and trees when spring comes? A The grass is turning green and trees are budding with fresh leaves. (Shim 1999: 253) Shim (1999) discusses articles twice under a heading of morpho-syntactic differences (between Korean and American English): the first is her suggestion that students are taught that a noun phrase must be preceded with the definite article when the noun phrase contains a relative clause so he is the man who can help other people (Shim’s example) must be used rather than he is a man who can help other people. Shim’s second point regarding articles is that Korean English allows for more variation in terms of count/noncount nouns and gives the example although it is a hard work, I enjoy it as an acceptable structure. For the purposes of this paper I accept Shim’s claims of codification as evidence that Korean English has begun to separate from related varieties. Note, however, that this study is now over twelve years old and there has not, to my knowledge, been a corpus-driven study published that highlights Korean English as it is actually used in the 21st century. With this lack of corpus-driven studies in mind I collected and transcribed two corpora of Korean spoken English for my PhD. The motivation for creating two corpora was to allow me to explore similarities and differences between Korean English as spoken by volunteers in Korea itself with that of comparable Korean volunteers speaking English in the UK. The theoretical basis for this paper is Hoey’s Lexical Priming which postulates that: 3 As a word is acquired through encounters with it in speech and writing, it becomes cumulatively loaded with the contexts and co-texts in which it is encountered, and our knowledge of it includes the fact that it co-occurs with certain other words in certain kinds of context. (Hoey 2005:8) Lexical Priming repositions the related phenomena of collocation and colligation at the very heart of language so that even traditional grammar is seen as a secondary output. The following ten priming hypotheses are posited: 1. Every word is primed to occur with particular other words; these are its collocates. 2. Every word is primed to occur with particular semantic sets; these are its semantic associations. 3. Every word is primed to occur in association with particular pragmatic functions; these are its pragmatic associations. 4. Every word is primed to occur in (or avoid) certain grammatical positions, and to occur in (or avoid) certain grammatical functions; these are its colligations. 5. Co-hyponyms and synonyms differ with respect to their collocations, semantic associations and colligations. 6. When a word is polysemous, the collocations, semantic associations and colligations of one sense of the word differ from those of its other senses. 7. Every word is primed for use in one or more grammatical roles; these are its grammatical categories. 8. Every word is primed to participate in, or avoid, particular types of cohesive relation in a discourse; these are its textual collocations. 9. Every word is primed to occur in particular semantic relations in the discourse; these are its textual semantic associations. 10. Every word is primed to occur in, or avoid, certain positions within the discourse; these are its textual colligations. Reproduced from Hoey (2012) Hoey (2005) argues that cultures harmonise their primings in three key ways: formal education, shared literary and religious traditions and the mass media. If we are primed then by television, radio, adverts, our friends, teachers, neighbours and family members - indeed every single instance of language we are exposed to - it would be reasonable to expect 4 measurable differences in the language used by two communities in two different countries even when they share a first language and cultural background. This study was developed to test such a hypothesis as well as to explore the level of similarity between the corpora. The following research questions have guided the study: 1 What are the key similarities between the two Korean English corpora in terms of the lexical environment around the articles a, an and the? 2 What are the key differences between the Korean corpora and two British reference corpora in terms of the lexical environment around articles? 3 To what extent can Lexical Priming theory account for any observed variation? Hoey (2005) makes use of selected 2-grams and 3-grams (amongst others) in his own analysis. On the face of it an analysis of function words may seem surprising (not least when one notes Hoey’s claim that every word has pragmatic and semantic associations) but Hoey provides a convincing argument that in the winter has different semantic primings from in winter – in his corpus of news articles from The Guardian; the former tends to occur with material process verbs whereas the latter tends to occur with relational process verbs which highlights the potential priming effects of the. The focus on function words is also likely to minimise variation depending on the topics discussed during data collection. Note Hoey’s (2005) caution - shared by the author - that concordance lines cannot be taken as direct evidence that speakers are primed (psychologically) to associate certain words and strings with other words and strings; the concordance lines and corpus data are to be seen as an indication of strings that could reasonably be seen as being primed. In a similar vein I share Hoey’s rejection of lemmatisation for the purposes of this study simply because one cannot assume different forms of a lexical item will share primings; get a job for example will be treated independently from got a job unless the data provide a reason to discuss common primings. Hoey (2005) also suggests that a speaker’s L2 primings will be superimposed on their L1 primings; this is clearly a complex relationship that requires further research but it will be touched upon in this paper and partially explains the choice of articles as the focus of this paper. Articles were chosen partially because there is no article system in the Korean language (and thus less obvious L1 interference) and, perhaps more so, because many of my students and 5 respondents reported that it was the most challenging aspect of learning and using English. Lee (2001) only refers to articles by stating that the Korean language does not have them while Ko et al. (2012) highlight a number of problems surrounding article use in Korean English but is based on analysis of very specific tasks consisting of the volunteers responding to prompts such as draw circles around the books during written and picture-based tasks rather than speech. Chuang and Nesi (2006) use a corpus-driven method to study article use in Chinese Written English and show that up to 29.7% (including problems with the zero article) of the learners’ errors are article related. It also seems reasonable to suggest that articles would be subject to subconscious priming effects (rather than the more conscious effects of education) while speakers are focussing on the (more salient) content of their speech. I begin with a brief summary of the two Korean corpora and two British comparator corpora that were used. 2 Four corpora The two spoken Korean English corpora were collected in Liverpool and Seoul in 2008 and are named SK (for Seoul Koreans) and LK (for Liverpool Koreans). For each recording the Korean informant and myself were situated in a small room as I began by asking questions about their reasons for studying English, hobbies and career ambition (for example); I aimed to keep the conversations as informal as possible and was keen to find a subject that would ‘get them talking’ freely without focussing on form. Table 1 shows that SK and LK were well matched for age and years of learning English but that SK has a more notable female bias. Ideally the number of speakers and gender balance would be better matched but difficulties finding respondents who were willing to be recorded speaking English prevented this. (Recall Park’s (2009) suggestion that Korean speakers tend to feel that they are poor at English and thus may be hesitant to volunteer for such studies.) 6 SK LK Number of respondents 39 28 Average age 25 27 Gender 29f (78%) 16f (57%) 8m (22%) 4 12m (43%) 9.7 12.2 Average years learning English Table 1: Korean informants The respondents in Liverpool had spent an average of two years living in the UK. My own utterances were removed from the main Korean corpora and not used in subsequent frequency counts but all audio files and complete transcripts were kept for reference. The total number of word tokens in each of the four corpora used in this study is shown in Table 2. Liverpool Korean corpus (LK) 83 446 Seoul Korean corpus (SK) 112 621 Scouse corpus (SCO) 106 562 Demographic section of spoken BNC (BNC) 3 945 881 Table 2: Corpus sizes 4 Two respondents in Seoul chose not to complete the demographic data sheet 7 As I was directly involved in preparing the Korean corpora great care was taken to keep them as comparable as possible; the comparator corpora, however, were not prepared specifically for this study so certain differences must be noted and taken into account. A corpus of native Liverpool spoken English or ‘scouse’ (SCO) was developed by a colleague between 2001 and 2004 (Pace-Sigge 2010) so I used this as a comparator corpus because of its similar size and to allow me to account for any possible influence of the local primings on the Liverpool (LK) volunteers. Note, however, that the SCO has a total number of 51 speakers, a larger proportion of males at 54%, the volunteers are slightly older than the Korean speakers with an average age of 33 and there is also a large number of group discussions compared with the one-to-one arrangement used for the Korean corpora. Finally the much larger demographic spoken section of the British National Corpus (BNC) was used. This is a large reference corpus with data collected by 124 volunteers in 38 UK locations in the section used for this study (What is the BNC? 2012) but with notably older recordings collected in 1991 and 1992 one has to be cautious about any language structures that may be changing in this timescale; the difference between the one-to-one interview-like type data collection in SK and LK and the freer recording used in the SCO and the BNC (including groups) must also be noted. All analysis was carried out using WordSmith tools version five (Scott 2011); a simple orthographic transcription was used for all the data and small differences such as the transcription of filled pauses (er and um) between the Korean data and SCO were not judged as being problematic for the current study. 3 The a environment Table 3 shows the frequency of the article a in each of the four corpora alongside the most frequent R1 collocates. L1 items would be affected by the speakers’ primings but R1 items were only focussed on in this paper in order to explore the relationship between the article and the other components of a noun phrase that follow. Note that while many R1 items would traditionally be seen as specific components of a noun phrase, for the purposes of this study I would see this as simply as colligation (a, for example, appears to colligate with quantifiers 8 such as lot and little in the data shown in Table 3) and I wish to avoid further assumptions about structure unless it comes out of the data. The column labelled dispersion shows how many files the string occurs in and shows that the strings under observation are evenly spread through the files rather than being clustered in one or two (and, particularly for SK and LK, this would suggest only one or two speakers are using the form). Table 3: Frequency details for a and most frequent R1 collocates in four corpora 3.1 a lot versus a bit The most frequent 2-gram in the three smaller corpora is a lot which is discussed in some detail in Hadikin (2011a) and Hadikin (2011b) so is not repeated other than to mention two key points. The first is that a high frequency 5-gram there are a lot of seems to be driving the very high frequency of 170 occurrences of a lot (or 1509 per million) seen in SK; SK contains 14 occurrences of there are a lot of compared to just 17 in the BNC which is 35 9 times larger (p < 0.0001 with two-tailed Fisher’s exact test (FE)). The second is the possible influence of the speakers’ first language form 많은 (manun) which is often used without any variation and glossed as there are/is a lot of in translation dictionaries. The LK data seems more heavily influenced by the string quite a lot which more closely reflects the percentage values in the British corpora; eight percent of the usage of a lot in LK consists of the string quite a lot compared with four percent in SCO and six percent in the BNC (Table 4). p = 0.25 when LK is compared with the BNC for quite a lot versus OTHER a lot and so the difference is not statistically significant but p = 0.0009 (two-tailed FE) when SK is compared with the BNC – this is clearly below the oft-cited cut off point of 0.05 for statistical significance (see Gries 2009 for example). Table 4: Frequency detail for a lot and quite a lot in four corpora Rather than the string a lot, this highest frequency position is occupied by a bit in the BNC and an important factor affecting the frequency of this 2-gram is the use of the string a bit of (Concordance 1). From the concordance this structure appears to be used for a number of functions ranging from the expression of large amounts (quite a bit of work) to somewhat fixed expressions (a bit of a pain). 10 Concordance 1: Sample concordance of a bit of from BNC 11 The normalised frequency of a bit of in the BNC is 264pm compared with 197pm in SCO and 9pm and 48pm in SK and LK respectively; this suggests that the form may not be established in Korean English (two-tailed χ2 with Yates’ correction is 22.5 when a bit of is compared with OTHER of in SK and the BNC, df=1, p <0.0001). Four occurrences in LK suggest that the form may be developing with the presence of a bit of a passion, two closely related strings relating to studies from two speakers: I studied a bit of sociology and I studied a bit of infectious disease and what appears to be a reformulation as a speaker produces we had a bit of we had a few complaints which suggests the speaker was primed to refer to small amounts as a bit of but then became aware of the problematic string we had a bit of complaints and reformulated. 3.2 a little bit Returning to Table 3 it is interesting to note that the string a lot takes up 15% of all uses of a in both Korean corpora while the corresponding figure is 4% in both British corpora. The variation of the second most frequent 2-gram, a little, in both Korean corpora appears to be less striking with 8% of SK, 6% of LK and 2% of the British corpora but these numbers hide a surprising point. The 3-gram a little bit takes up 78% of all a little strings in SK, 79% in LK but just 31% and 32% in SCO and the BNC (see Table 5, p <0.0001 when a little bit is compared with a little OTHER for SK and the BNC, two-tailed FE). After the highest frequency of 70 occurrences of a little bit in SK the second most frequent a little * string is a little different but with just three occurrences there is a notable drop in frequency that is shared with LK. It seems reasonable to suggest that speakers of Korean English are primed to use the string a little bit and that this may partially explain the smaller frequencies of the string a bit seen in Table 3. The phrase a little bit appears as an adjective modifier in most cases with examples ranging from a little bit different and a little bit better to a little bit free and a little bit hard; this could reflect the L1 primings for the item 조금 (chokum). 12 Table 5: Frequency details for a little and high frequency R1 items in four corpora 3.3 get a job This final section, before moving on to the an environment, centres on the third most frequent a * 2-gram in SK: a job. It stands out amongst the other top four frequent 2-grams in that it is a psychologically complete unit that does not refer to an amount (cf. a lot, a little, a very, a few, a bit and a good). This should not come as a complete surprise considering that many of the informants were students and were likely to be practising English to improve their job prospects but, as is often the case, the lexical environment that this particular 2-gram carries with it tells a story about the primings of the informants that may mark Korean English as subtly different from other varieties. 13 Table 6: Frequency and percentage chart for the 3-gram get a job (based on Biber 2009) In this case it appears that the Korean English speakers are primed to use the string get a job and I will use a technique inspired by Biber (2009) to highlight the ways in which this string is used differently in the corpora. Table 6 shows three main data columns: the first showing data for the frequency of the string get a job compared with the total frequency of * a job strings, the second column compares get a job with all get * job strings and the final column compares get a job with all get a * data. As an example, the highlighted parts of Table 6 show that there are 14 occurrences of get a job out of a total 25 occurrences of all * a job strings in SK and, in the lower part of the chart, that this is equivalent to 56%. Recall that the dispersion column shows the number of files in which the string occurs so get a job, for example, occurs in seven different files in SK and this corresponds with seven different speakers. This 56% value for SK combined with a figure of 77% for LK shows a clear level of relative fixedness when compared with the equivalent figures in the British corpora: 14% in SCO and 13% in the BNC (p < 0.0001 when get a job is compared with OTHER a job in SK and the BNC, two-tailed FE). Concordance two shows the range of contexts in which the 2-gram a job occurs in the BNC (in a sample of data) while the Korean data consists largely of strings such as I want to get a job and any chance to get a job which could easily be influenced by the fact that the data were collected in a university setting and many informants were involved in looking for a job. The speakers would, in terms of traditional grammar, have had the option to say I want a job or any chance of a job in this context, however, so we are left 14 with a mixed picture. Korean speakers may be primed to use the string get a job more strongly than British speakers in a range of contexts but the data sets are not comparable enough for a strong claim at this point. A study based on a comparison between a corpus of Korean English and a purpose built, directly comparable corpus of spoken British English would be useful to further explore this area. Note, however, that while the same limitation might be expected to suggest primings for the string got a job a rather different picture emerges. In the Korean data the item got shows a much weaker attraction to a job when compared to get a job (just 16% of * a job strings are filled with the item got in SK compared with 8% in LK, 7% in SCO and 14% in the BNC. One’s attention is drawn more to the third element when conducting a got a job analysis with 22% of SK showing the item job in the got a * frame compared with just 8% of LK, and 1% in each of SCO and the BNC thus highlighting the need for caution when it comes to lemmatisation. Concordance 2: Sample concordance of a job in the BNC The fully fixed status of the article in the string get a job is clear from the two figures of 100% in Table 6: SK and LK show no variety at all. SCO and the BNC have figures of 67% and 61% respectively though it should be noted that there are only three occurrences of get * job in SCO; the 33% comes from a single use of get your job back. The variety in the BNC is interesting in that 24% of the get * job frame makes use of the article the and could reasonably have been expected to appear in the 24 lines of Korean data if speakers shared 15 similar primings (p = 0.004 when get a job is compared with all other get * job strings for SK and the BNC, two-tailed FE). The third column in Table 6 shows some of the greatest differences between the Korean corpora and the British corpora; the item job completes the get a * frame in just 3% of cases in the BNC, for example, compared with a figure more than 10 times larger - 37% - in SK (p < 0.0001, two-tailed FE). SCO BNC 1 few 1 bit 2 car 2 lot 2 grant 2 lot 2 bit 2 big 2 job Table 7: Items occupying R1 position following get a in British corpora The apparent British primings for the colligation a QUANTIFIER influence these data with get a few forming the most frequent get a * 3-gram in SCO and the items car, grant, lot, bit and big occurring at the same frequency of job with two occurrences each (see Table 7). The strings get a bit and get a lot are the most frequent get a * strings in the BNC but get a job is clearly the most frequent in both Korean corpora. The Korean corpora have no occurrences of the BNC’s most frequent get a * 3-gram get a bit though there are two occurrences in SCO (19pm) and 104 occurrences in the BNC (26pm). SCOs most frequent get a * 3-gram get a few is also completely absent from both Korean corpora (there are three occurrences in the similar sized SCO (28pm) and 40 occurrences in the BNC (10pm)). This suggests that get a QUANTIFIER strings are used rather differently in 16 Korean English but the potential combined primings for delexicalised verbs (see Chi, Wong and Wong 1994 for a study of learners in Hong Kong for example), articles and quantifiers give a complex picture that would be beyond the scope of this study. 4 The an environment The lexical environment surrounding the item an in the four corpora is clearly rather different than that of a as Table 8 shows. Table 8: Frequency details for an and most frequent R1 collocates in four corpora There are very few obvious similarities in the most frequent ten items that follow an (though note that the Korean data shown contains a number of single occurrences). The rather low normalised frequencies of an (222pm in SK and 467pm in LK) are quite striking however compared with the British corpora (1398pm in SCO and 1303 in the BNC); ratios of the 17 frequency of a to an are 45-1 in SK, 21-1 in LK, 11-1 in SCO and 15-1 in the BNC which clearly positions LK between SK and the comparator corpora and may suggest primings are shifting to a British level. LK stands out amongst the four corpora, however, in that the string an hour is not the most frequent an * 2-gram. It is possible that these speakers are primed to say thirty minutes rather than half an hour (the most frequent * an hour string in both SCO and the BNC); this would reflect my experience of teaching time phrases in Korea and, indeed, LK has the highest normalised frequency of the string thirty minutes at 48pm. SK has 18pm, the BNC has just 3pm and there are no occurrences at all in SCO. Clearly, a Korean preference for the thirty minutes form does not explain why SK differs from LK but note that SK only has 25 occurrences of an so is particularly susceptible to statistical variation and that the most influential * an hour 3-gram in SK is for an hour rather than half an hour; it is perhaps something of an illusion that SK is more closely aligned with the British corpora. Concordance 3: Complete concordance of an * student in LK The item hour is not only absent from the top of the an * frequency list in LK, it ranks sixth below international, English, exchange, interview and essay. These items suggest a possible priming based on the concept of international student activities which would be understandable considering the demographics of the informants. Such an explanation should not take away from the fact that this is a difference between SK and LK (potentially) based on recent primings (note, however, that the difference between an hour and other an * strings in SK and LK is not statistically significant with p=0.199, two-tailed FE). The an * student frame shown in Concordance 3 is, in fact, more frequent than the most frequent 2-gram an international in LK and lends support to this idea. 18 5 The the environment In this final analysis-based part of the paper I will be discussing areas of the the environment as it is shown in Table 9. The frequencies of the most frequent the * 2-grams are much lower than a * 2-grams, particularly in the Korean corpora, but it is notable that there is a clear division between the Korean data and the British data: the Korean corpora make greatest use of the string the first while the British corpora make greater use the string the other. For this reason as well the fact that both strings are available for the formation of longer noun phrases I will take these forms as my starting point. (Recall that I am cautious about simply assuming that structures such as noun phrases have an important role in corpus-driven studies but Korean learners are taught phrase structure from an early age so it is reasonable to think about the primings effects of such an education.) Table 9: Frequency details for the and most frequent R1 collocates in four corpora 19 5.1 the first time The first is the most frequent the * 2-gram in the Korean data with normalised frequencies of 611pm and 462pm in LK and SK respectively; by comparison the normalised frequencies for SCO and the BNC are 197pm and 270pm. The 3-gram the first time is the most frequent the first * 3-gram in each of the corpora so I selected this string to produce the frequency chart shown in Table 10. Table 10: Frequency and percentage chart for the 3-gram the first time (based on Biber 2009) Compared to the chart shown in Table 6, and other charts in Hadikin (2011a) and Hadikin (2011b) Table 10 is quite unusual because the Korean corpora show the most flexibility in the first slot while the British corpora appear somewhat fixed. 20 Concordance 4: Sample concordance of first time in SK Concordance 4 shows a sample concordance from SK where the following strings can be seen: 1 when I look back first time 2 when I met him first time 3 in Korea at first time This suggests that many of the speakers are weakly, if at all, primed to insert the item the before the 2-gram and may be primed to use the string first time in similar ways to the way a British speaker simply uses first or at first (p < 0.0001 when the first time is compared with other * first time strings in SK and the BNC, two-tailed FE). Indeed, LK has seven occurrences of at first time which highlights this potential example of mixed primings (there are three occurrences in SK and none in either SCO or the BNC). The second column of Table 10 returns to a more familiar pattern of the string in the Korean data appearing more fixed with 100% of the * time strings taking the form the first time in LK, 58% in SK but just 25% in both SCO and the BNC. It is a curious point that to a large extent (12/34 occurrences or 35% of all the * time occurrences) the variation comes from the use of the same time in SK which is completely absent in LK; there is a single occurrence of same time as a 2-gram. With 5/16 occurrences (31%) SCO actually has the only time as its 21 most frequent the * time phrase and the BNC has the first time as its most frequent (138/724 or 19%) followed by the same time (129/724 or 18%) and the next time (45/724 or 6%). The percentage of the first * that takes the form the first time shows that there is a certain amount of flexibility in all four corpora; LK shows the most fixedness but with just 45% of the concordance in the form the first time there is actually a large set of other strings such as the first thing, the first floor and the first one. It seems that the numbers are most notably affected by the high normalised frequencies of the first time in the Korean corpora – 178pm in SK and 276pm in LK compared to 38pm in SCO and 45pm in the BNC. This appears to be the result of a more general use that compares and overlaps with the meaning of at first in British English (p=0.55 when the first time is compared with other the first * strings in LK and SK but 0.0003 between SK and the BNC, two-tailed FE). 5.2 the other This most frequent the * 2-gram in both SCO and the BNC does not lend itself as readily to analysis by a frequency/percentage chart as it tends to form quite different longer strings depending on whether one is looking at the Korean corpora or the British. In both SK and LK it has a tendency to form and the other but in SCO one mostly finds the other side and in the BNC the most notable 3-gram is the other one. SK stands alone in its high relative use of and the other compared to the total number of * the other strings with 14/38 (37%) compared to 5/35 (14%) in LK, 2/48 (4%) in SCO and 202/2918 (7%) in the BNC (p = 0.035 when SK is compared with LK, two-tailed FE). 22 Concordance 5: Complete concordance of and the other in SK (above) and LK (below) Use of and the other shown in Concordance 5 shows that the string is being used mostly for comparisons or for the addition of a new point in the conversation in both Korean corpora. A colligation and the other thing BE is noteworthy with a presence in both corpora shown in Concordance 5 but is not present in SCO and only occurs six times in the near four million word section of the BNC (cf. four times in the much smaller SK) always in the same form and the other thing is; the Korean informants appear to be more strongly primed to use this string/colligation to add information without necessarily specifying that they were going to make two or more points earlier in the discourse as one may expect (p = 0.002 when and the other thing is compared with other and the other * strings in SK and the BNC, two-tailed FE). The most frequent * the other/the other * string in SCO is the other side which makes it appear somewhat different from both the Korean corpora and the BNC. 11/48 (23%) occurrences of the other form this 3-gram in SCO and are mostly used to refer to physical or geographic areas (the other side of the Liverbuilding, the other side of Wigan etc) though it is 23 important to note that four of the occurrences were produced by the researcher himself. There are no occurrences of this string in the Korean corpora which may suggest different primings; 279/2919 (10%) are the corresponding figures for the other side in the BNC and it appears to be used with a similar function of describing physical locations. The most frequent 3-gram in the BNC’s the other environment is the other one with 480/2919 (16%) of all the other * strings taking this form compared with 3/48 (6%) in SCO, 3/38 (8%) in SK and 1/35 (3%) in LK. The right side of the string the other in the Korean corpora appears to be more flexible than in the British corpora; recall that 23% of the other * in SCO takes the form the other side and 16% of the other * in the BNC takes the form the other one. The most frequent the other * in SK is the other thing with 4/38 (11%) of occurrences and the most frequent the other * 3-gram in LK is the other countries with 3/35 (9%) in this form. Despite this apparent R1 flexibility time expressions such as the other day, the other week and the other night are conspicuously absent from 38 lines of the other in SK but these forms make up 23% of the BNC’s the other * occurrences, 21% of SCO’s and 9% of LK’s occurrences (a single occurrence in SK would have represented approximately 3%); this suggests that the informants in SK are weakly primed or, possibly, not primed to use the other in time expressions but the LK informants may have begun a shift to British primings during their time in the UK (Concordance six illustrates the lack of time expressions in SK, p=0.105 when LK is compared with SK for time expressions but p < 0.0001 when SK is compared with the BNC). 24 Concordance 6: Sample concordance of the other in SK showing R1 flexibility but a lack of time expressions 25 6 Conclusion In this paper I have tried to show some of the variety as well as the consistency of the English spoken by Korean adults by discussing three lexical environments: the phraseology and lexis surrounding the items a, an and the in two small corpora of Korean English and, as comparator corpora, a small ‘scouse’ corpus and the spoken demographic section of the BNC. Some of the similarities between the Seoul Korean corpus (SK) and the Liverpool Korean corpus (LK) include the following: The percentage of a * that takes the form a lot is consistent at 15% and this is notably higher than the British corpora. The percentage of a little * that takes the form a little bit is very similar at 78% (SK) and 79% (LK); this is also much higher than the British corpora. The string get a job shows a comparable level of fixedness in the Korean corpora with 100% of get * job taking the form get a job, for example, compared with 67% and 61% in SCO and the BNC. The item an occurs with very low normalised frequency in the Korean corpora: 222pm and 467pm in SK and LK compared with 1398pm and 1303pm in the BNC. The string the other has a strong tendency to form the 3-gram and the other in the Korean corpora compared to SCO and the BNC which tend to form R1-based the other * strings. While differences between SK and LK include: LK has a greater frequency of quite a lot than SK despite being approximately 25% smaller. LK stands out amongst the four corpora because it does not have an hour as the highest frequency an * 2-gram LK has a higher frequency of at first time than SK 26 LK uses the other to form time expressions such as the other day and the other night but there are no occurrences in SK This kind of variation suggests that while priming effects may separate LK from SK in certain areas, other strings are being used with great consistency. Similarities such as the high frequency use of a lot, for example, are arguably influenced by a comparable L1 form and consistent translation across pedagogic materials - Korean learners may be using a lot with a comparable frequency to the Korean equivalent 많은 (manun); their primings are then reinforced by high exposure to a lot when reading Korean English texts - but then, as language researchers, we might ask how and why the speakers are primed to use this English form as part of longer utterances. The SK speakers appear primed to produce there are a lot of while LK speakers appear more likely to say quite a lot. This arguably reflects a recent change to a British priming as the LK speakers rely less on there are a lot of (possibly stored as a formulaic chunk for many speakers and an exact translation of its Korean equivalent) and begin to include a hedging term quite that they will have been exposed to in the UK. It is also interesting to note that a colligation appears to have crossed over from the L1: for each article under consideration in this paper the normalised frequencies are lower in the Korean data compared to the British data. The article a occurs in SK at a normalised rate of 10 176 pm but 19 621 pm in the BNC, for example, and this pattern is consistent across the data for an and the suggesting that noun phrases are weakly primed for colligation with articles in Korean English. In at least one case British-like primings appear to have come together to create a uniquely Korean result: the primings for at first and first time appear quite unexceptional but then combine to give a high frequency of at first time with its own function of referring to the first time something is done or experienced. Lexical Priming is arguably unique in that its focus on the primings of each word (which is actually shorthand for the primings of the language user’s or users’ use of that word) allows for a detailed consideration of how and why a string appears to be changing form. I hope that this paper has highlighted some of the areas of spoken language which might be expected to show priming effects whereas until now any suggestions would have been merely theoretical (Hoey 2005 was largely based on written texts). The issues discussed here may also suggest which areas of spoken English are the first to change when individuals move 27 into a new geographical area and which parts of one’s idiolect are relatively fixed or slower to change – this could have exciting implications for both pedagogy and language evolution. Many of these changes of language forms could, of course, be discussed without reference to Lexical Priming but the alternative model would need to account for communities and individual speakers on both a psychological and sociological level changing their collocational behaviour in a short space of time – linguistic models such as those proposed in Sinclair (1991) and Wray (2002) are suitable but are also generally compatible with Lexical Priming as discussed in Hadikin (2011a) and Hadikin (2011b). Wray (2002), however, argues that learners tend to break down chunks into their parts based on meaning thus leaving a fuzzy picture when it comes to function words; it is not clear how the details of Wray’s model could explain how LK speakers have manipulated the strings at first and first time to create a new form, for example. The work also raises research questions such as ‘how and why do individuals vary in their use of a lot?’, for example, and pedagogic questions such as how alternatives could be taught or, indeed, if it is actually beneficial to try to reproduce the primings of native speakers. The need for very carefully chosen/carefully prepared comparator corpora is a further issue raised because the differences between interview-type data in the Korean corpora and the wider contexts recorded in the comparator corpora will interfere with and exaggerate any ‘true’ differences between the language varieties. There are, however, very few papers published about Korean spoken English so I hope this one can add to the developing picture of corpus-based language variation and act as a starting point for further research work as well as providing Korean learners, language users and teachers with, what some may see as points to notice (in the sense of Schmidt 1990) such as an overall tendency to drop articles while, to others, these are simply differences between two equally valid World Englishes and in many cases the speaker’s meaning would be unhindered. 28 References Biber, D. 2009. A corpus-driven approach to formulaic language in English: multi-word patterns in speech and writing. Presentation given at Corpus Linguistics 2009 on 23rd July 2009. Chi, A.M., Wong, K.P. and Wong, M.C. 1994. ‘Collocational problems amongst ESL learners: A corpus-based study’ in L. Flowerdew and A.K.K. Tong, Entering text. Hong Kong: Language Centre, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, and Department of English, Guangzhou Institute of Foreign Languages, pp. 157-165. Chuang, F. and Nesi, H. 2006. ‘An analysis of formal errors in a corpus of L2 English produced by Chinese students’, Corpora 1(2): 251-271. Crystal, D. 2003. The Cambridge Encyclopaedia of the English Language (2nd Edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gries, S. 2009. Quantitative Corpus Linguistics with R. London: Routledge. Hadikin, G. S. 2011a. Corpus, Concordance, Koreans: a corpus-driven study of an emerging New English. Manuscript submitted for publication. Hadikin, G. S. 2011b. Corpus, Concordance, Koreans: a comparison of the spoken English of two Korean communities. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Liverpool. Hoey, M. 2005. Lexical Priming: a New Theory of Words and Language. London: Routledge. Hoey, M. 2012. Priming hypotheses. Retrieved from http://lexicalpriming.org/priminghypotheses/. Ionin, T., Baek, S,. Kim, E., Ko, H. and Wexler, K. 2012. ‘That’s not so different from the: definite and demonstrative descriptions in second language acquisition’, Second Language Research, 28, 69-101. Kachru, B. and Nelson, C. 2006. World Englishes in Asian contexts. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. Lee, I. and Ramsey, R. 2000. The Korean Language. Albany, NY: SUNY press. Lee, J. 2001. ‘Korean speakers’ in Swan, M. and Smith, B. (eds.) Learner English: a teacher’s guide to interference and other problems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. McArthur, A. 1987. The English Languages? English Today 11, pp 9-13. Mehlsen, C. 2011. The Rise of Multiculturalism in Korea. Retrieved from http://www.dpu.dk/fileadmin/www.dpu.dk/ialeimagazine/multiculturaleducation/IALEI_ Magazine_18-20.pdf. 29 Pace-Sigge, M. T. L. 2010. Evidence of lexical priming in spoken Liverpool English. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Liverpool. Park, J. S. 2009. The Local Construction of a Global Language: Ideologies of English in South Korea. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Porter, C. 2011. ‘Review of ‘The Local Construction of a Global Language: Ideologies of English in South Korea’’, TESL-EJ 14 (4). Schmidt, R. 1990. The role of consciousness in second language learning. Applied Linguistics 11, pp 17-46. Scott, M. 2011. Wordsmith tools. Retrieved from http://www.lexically.net/wordsmith/index.html. Shim, R. J. 1999. Codified Korean English. World Englishes 18 (2), pp. 247-259. Sinclair, J.McH. 1991. Corpus, Concordance, Collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Tollefson, J. 2002. Language Policies in Education: Critical Issues. Routledge: London. Wray, A. 2002. Formulaic Language and the Lexicon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Yemi-Komshian, G., Flege, J. and Liu, S. 2000. ‘Pronunication Proficiency in the First and Second Languages of Korean-English Bilinguals’, Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 3 (2) pp. 131-49. What is the BNC? 2012. Retrieved from http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk/corpus/index.xml?ID=intro. 30