university of florida thesis or dissertation formatting template

advertisement

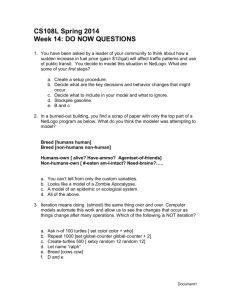

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 Winter diets of immature green turtles (Chelonia mydas) on a northern feeding ground: integrating stomach contents and stable isotope analyses Natalie C. Williams1,2*, Karen A. Bjorndal2,3, Margaret M. Lamont2,4, Raymond R. Carthy1,2,4 1 Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, University of Florida, Gainesville FL 32611, USA 2 Archie Carr Center for Sea Turtle Research University of Florida, Gainesville FL 32611, USA 3 4 Department of Biology, University of Florida, Gainesville FL 32611, USA Florida Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, U.S. Geological Survey, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA Running head: immature green turtle diets * Email: natalie.williams@ufl.edu Phone: 352-214-5842 This draft manuscript is distributed solely for purposes of scientific peer review. Its content is deliberative and predecisional, so it must not be disclosed or released by reviewers. Because the manuscript has not yet been approved for publication by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), it does not represent any official USGS finding or policy. 1 48 49 Abstract 50 The foraging ecology and diet of the green turtle, Chelonia mydas, remain understudied, 51 particularly in peripheral areas of its distribution. We assessed the diet of an aggregation of 52 juvenile green turtles at the northern edge of its range during winter months using two 53 approaches. Stomach content analyses provide a single time sample, and stable isotope analyses 54 integrate diet over a several-month period. We evaluated diet consistency by comparing the 55 results of these two approaches. We examined stomach contents from 43 green turtles that died 56 during cold stunning events in St. Joseph Bay, Florida, in 2008 and 2011. Stomach contents were 57 evaluated for volume, dry mass, percent frequency of occurrence, and index of relative 58 importance of individual diet items. Juvenile green turtles were omnivorous, feeding primarily 59 on seagrass and tunicates. Diet characterizations from stomach contents differed from those 60 based on stable isotope analyses, indicating the turtles are not feeding consistently during winter 61 months. Evaluation of diets during warm months is needed. 62 63 Keywords: Green turtle; Chelonia mydas; cold stun; St. Joseph Bay, Florida; carbon and 64 nitrogen stable isotopes 65 66 Introduction 67 The life history of green turtles (Chelonia mydas) involves a series of ontogenetic habitat and 68 resource shifts (Bolten, 2003). After completing an initial oceanic life stage, small juvenile green 69 turtles (20 to 35 cm curved carapace length) in the western Atlantic become residents of neritic 70 habitats, where they feed primarily on seagrasses and/or macroalgae, but may also consume 71 animal matter (Bjorndal, 1997; Mortimer, 1981). Variation in feeding patterns is thought to be 2 72 dependent on prey abundance and availability (Guebert-Bartholo et al., 2011) but may also be 73 affected by feeding selectivity (Bjorndal, 1985; Fuentes et al., 2006; López-Mendilaharsu et al., 74 2008). Variation in feeding patterns has been observed in subtropical systems (Guebert-Bartholo 75 et al., 2011; Nagaoka et al., 2012) where resource availability is relatively stable. In temperate 76 systems, resource availability is more variable; changes in seasonal biomass of vegetation and 77 animal prey may lead to greater variation and plasticity in feeding patterns. For these reasons, it 78 is critical to understand how tropical/subtropical species at the latitudinal extremes of their range 79 cope with environmental variation. 80 Studies on the diet of West Atlantic green turtles have been primarily conducted in the core 81 areas of their range using stomach content analysis. Mortimer (1981) examined the stomach 82 contents of 243 adult and subadult turtles in Caribbean Nicaragua. The main diet items, in 83 decreasing order of importance, comprised the seagrass Thalassia testudinum, three other species 84 of seagrass, 40 different algae species, benthic substrate, and animal matter. Turtles were found 85 to modify their diet opportunistically, based on the composition of available prey sources. For 86 example, during migrations to breeding grounds, where turtles travel near shore, they consume 87 more red algae and lignified terrestrial plant debris (Mortimer, 1981). Studies in several foraging 88 grounds along the coast of Brazil have reported varied diets between locations, with some diets 89 dominated by algae and others by animal matter. For example, in northern Brazil, Ferreira (1968) 90 documented that juvenile and adult (31–120 cm curved carapace length) green turtle diet is 91 composed of approximately 88% marine algae and less than 10% animal matter in an area where 92 seagrass is not abundant. The following types of animal matter were found: ascidians, molluscs, 93 sponges, bryozoans, crustaceans, and echinoderms. In a lagoon complex in southeastern Brazil, 3 94 green turtles consumed an omnivorous diet composed of four diet categories: terrestrial plants, 95 algae, invertebrates, and seagrass (Nagaoka et al., 2012). 96 Gilbert (2005) found that green turtles foraged selectively on Rhodophyta and Chlorophyta 97 on Ambersand Reef, Indian River County, Florida. In contrast, Mendonça (1983) found 98 immature turtles grazed exclusively on seagrasses and avoided the abundant algae species in 99 Mosquito Lagoon, Florida. Juvenile green turtles off the coast of Long Island, New York, feed 100 primarily on the seagrass Zostera sp. and marine algae (Burke et al. 1993). New York waters 101 provide a seasonal foraging ground for several sea turtle species from June through November 102 (Burke et al., 1993). Burke’s research represents one of the few available studies that examine 103 green turtle diet at the edge of their range. Few reports are available on green turtle diet in the 104 Gulf of Mexico. During a three year study in South Padre Island, Texas, Coyne (1994) reported 105 immature green turtles feeding selectively on algae and seagrass. Similarly, in St. Joseph Bay, 106 Florida, which lies on the north coast of the Gulf of Mexico, Foley et al. (2007) found that the 107 primary diet constituent of stranded green turtles from the 2000/2001 cold stunning event was T. 108 testudinum. Small quantities of tunicates (Styela sp.; Molgula sp.) were found in stomach 109 contents from green turtles in the 2000/2001 cold stunning event in St. Joseph Bay (J.M. 110 Lessmann, unpubl. report, 2002). 111 In habitats with low winter temperatures, juveniles in neritic habitats can either migrate to 112 warmer waters or overwinter in the neritic habitat. In temperate climates, adult turtles migrate 113 long distances to overwinter in warmer waters (Meylan, 1995). However, juvenile turtles 114 foraging in shallow bays with restricted entrances may face rapid decreases in water temperature 115 and be unable to escape (Mendonca and Ehrhart, 1982). St. Joseph Bay, Florida, provides the 116 opportunity to study foraging behavior of green turtles on the northern edge of the Gulf of 4 117 Mexico. Despite cool winter temperatures (4 to 35°C), green turtles remain in St. Joseph Bay 118 throughout the year, often remaining in the area for several years (McMichael 2005). The green 119 turtles in St. Joseph Bay are susceptible to cold stunning events, with 401 turtles stranding in 120 December 2000/January 2001 (Foley et al., 2007) and 1,670 turtles stranding in 2010 (Avens et 121 al., 2012). Foley et al. (2007) reported a diet dominated by seagrass from turtles killed by the 122 2000/2001 cold stunning event. However, seagrasses are known to experience decreases in 123 abundance during the winter in St Joseph Bay (Leonard and McClintock, 1999). Diets of green 124 turtles in temperate foraging grounds, especially during winter foliage reductions, are poorly 125 studied. 126 We investigate the diet of green turtles during winter in St. Joseph Bay using two 127 approaches. First, we analyzed stomach contents from 43 green turtles that died during cold 128 stunning events in St. Joseph Bay, Gulf County, Florida in 2008 (n=12) and 2011 (n=31). 129 Stomach contents give a direct measure of diet, but only for a short window of time. Second, we 130 used analyses of C and N stable isotopes of epidermis samples from 39 green turtles in 2011 to 131 evaluate consistency of diet over a longer temporal scale because stable isotope values of 132 epidermis represent an integration of diet over several months. Fig. 1 presents a conceptual 133 model comparing the isotope values of individuals in a population with inconsistent and 134 consistent feeding patterns. If individuals in a population have not fed consistently, their stable 135 isotope values will not be associated with the stable isotope value of the major diet item from the 136 stomach contents (Fig. 1a). If individuals in a population have maintained a relatively consistent 137 diet over the previous months, their epidermis stable isotope values should be higher than the 138 major diet item from the stomach contents, the distance representing the discrimination value 139 (Fig. 1b). Evaluating feeding consistency using both stomach content and stable isotope analyses 5 140 allows us to investigate alternative foraging strategies that may have been missed with previous 141 methods (Vander Zanden et al. in press). Examination of individual resource use patterns 142 through time may show significant intrapopulation differences and have important ecological 143 and conservation consequences (Vander Zanden et al. 2010). 144 145 Materials and methods 146 Study Area 147 St. Joseph Bay, Florida (29.76º N, 85.35º W), in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico, covers 148 an area just less than 30,000 hectares. St. Joseph Bay (SJB) is approximately 21 km in length, 149 with a maximum width of 8 km. The maximum depth is 13.3 m in the northern end, with a 150 minimum depth of 1.0 m in the southern end (McMichael, 2005). The site has a tidal range of 151 approximately 0.47 m, a very low current flow and highly organic sediments. The salinity in the 152 bay is similar to adjacent areas in the Gulf of Mexico (Stewart and Gorsline, 1962) and averages 153 35.0 ppt (Preserves, 2008). Water temperatures range from 4 to 35°C (McMichael, 2005). Wind 154 direction is usually north in the winter and south in the summer. The bay is productive due to its 155 salt marsh and seagrass habitats; seagrass beds are a prominent feature in the southern end and 156 cover approximately one-sixth of the bay. The abundance and distribution of seagrasses and 157 macroalgae in SJB are not fully known, and future research is needed to determine seasonal 158 dynamics, biomass, and productivity of these communities (Preserves, 2008). The local, 159 dominant seagrass species are Thalassia testudinum, Halodule wrightii and Syringodium 160 filiforme. Green turtles in St. Joseph Bay are susceptible to cold stunning events when water 161 temperatures decline to less than 10°C (Morreale et al., 1992; Schwartz, 1978; Witherington and 162 Ehrhart, 1989). These events are not uncommon along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts during 163 autumn and winter months (Avens et al., 2012), particularly in shallow waters with restricted exit 6 164 points (Foley et al., 2007). In exceptionally cold years (i.e. 2010 event), temperatures may 165 remain below 10°C for as long as two weeks (Avens et al., 2012; Foley et al., 2007) resulting in 166 high levels of cold stunning. Green turtles are present year-round, and at least some individuals 167 are resident for several years in St. Joseph Bay despite the potential for cold temperatures 168 (McMichael, 2005). 169 Sample Collection 170 In January 2008 and 2011, volunteers collected green turtles that stranded dead during cold 171 stunning events in St. Joseph Bay, Florida. Curved carapace length (CCL; cm) was measured 172 using a tape measure (Bolten, 1999). Body mass (kg) was measured using a hanging spring scale. 173 Stomach contents were removed from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and frozen pending analyses. 174 Epidermis tissue from the dorsal surface of the neck was collected using a 6-mm biopsy punch 175 and preserved in dry NaCl until analysis. For stable isotope analysis, epidermis samples were 176 rinsed with distilled water to remove the NaCl and the outermost epidermis was separated from 177 the dermis tissue using a scalpel blade. 178 Known prey items identified from stomach contents were opportunistically collected from 179 SJB in fall 2011 for stable isotope analysis. This collection period was chosen to best represent 180 the season in which diet item isotope values would be incorporated and represented in epidermis 181 tissue from the stranded turtles. The following known prey items were sampled: seagrasses (T. 182 testudinum, H. wrightii, and S. filiforme), macroalgae (Gracilaria sp. and Enteromorpha sp.), 183 and tunicates (Botrylloides sp.). The sample size was two for each species. Samples were put in a 184 cool box for transport, rinsed with distilled water, and then frozen at -20C. For all plant items, a 185 razor blade was used to remove epibionts from blades and stems prior to drying. A subset of 186 samples (seagrasses, macroalgae, tunicates) were treated with 1N HCl using the drop-by-drop 7 187 method of Jacob et al. (2005), and, upon seeing no release of CO2, it was concluded that 188 acidification was not necessary for the samples. 189 Frozen stomach contents were thawed and separated to species or the lowest identifiable 190 taxon, using a dissecting scope when necessary. Each diet item was quantified using percent 191 frequency of occurrence, volume, mass, and index of relative importance (IRI). Percent volume 192 was evaluated by water displacement using graduated cylinders; diet items less than 0.2 ml were 193 considered “trace”. Diet items were dried at 60°C for 24 hours and then weighed to calculate 194 mass. IRI was modified from Hyslop (1980) by Bjorndal et al. (1997) for application to 195 herbivores. Each diet category was calculated by the following equation: IRI 100(FiVi ) n (F V ) i i 196 i1 197 198 where F is percent frequency of occurrence, V is percent volume, and n is the number of diet categories. Each of these measures (volume and frequency) in isolation can yield misleading 199 interpretations (Bjorndal et al., 1997; Hyslop, 1980). For example, a diet item with a 100% 200 frequency of occurrence may only be present in each stomach in trace amounts. The IRI provides 201 a better interpretation for ranking the relative importance of diet categories because both 202 frequency and volume are included (Bjorndal et al., 1997). 203 Of the total individual samples (n=49) for 2011, only individual total sample volumes 204 greater than 9.0 ml were included as representative samples of turtle diet (n=31). We compared 205 results from all samples with those from samples >9.0 ml to test for an effect of volume on 206 estimates of diet composition. Small sample volumes occurred only in 2011. 8 207 Stable isotope analyses 208 For stable isotope analysis, approximately 0.5 to 0.6 mg of each epidermis sample and 1.0 209 to 15.0 mg of each prey sample was weighed and sealed in a tin capsule. Samples were analyzed 210 for δ13C and δ15N by combustion in a ECS 4010 elemental analyzer (Costech) interfaced via a 211 ConFlo III to a DeltaPlus XL isotope ratio mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific) in the 212 Department of Geological Sciences at the University of Florida, Gainesville. Sample stable 213 isotope ratios relative to the isotope standard are expressed in the conventional delta (δ) notation: δX = [(Rsample/Rstandard) – 1] × 1000 214 215 where δX is the relative abundance of 13C or 15N in the sample expressed in parts per thousand 216 (‰) and Rsample and Rstandard are the corresponding ratios of heavy to light isotopes (13C/12C and 217 15 218 N/14N) in the sample and international standard, respectively. The standard used for 13C was Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite and atmospheric N2 for 15N. All 219 analytical runs included samples of standard materials that were inserted at regular intervals to 220 calibrate the system. The reference material USGS40 (L-glutamic acid) was used to normalize all 221 results. The standard deviation of the reference material was 0.04‰ for δ13C and 0.08‰ for δ15N 222 values (n=10). Repeated measurements of a laboratory reference material, loggerhead (Caretta 223 caretta) scute, was used to examine consistency in a homogeneous sample with similar isotopic 224 composition to the epidermis samples. The standard deviation of the loggerhead scute was 225 0.06‰ for δ13C values and 0.10‰ for δ15N values (n=4). 226 To evaluate feeding consistency, we assigned each turtle for which we had >9.0 ml 227 stomach samples and isotope values (n=19) to one of three categories based on their stomach 228 contents: >50% seagrasses, >50% macroalgae and >50% tunicates. We then plotted the stable 229 isotope values of these turtles and the prey species. We compared the resulting graph (Fig. 2) 230 with the conceptual model to determine whether turtles were feeding consistently. We did not 9 231 adjust stable isotope values of turtle skin for diet-tissue discrimination. Such an adjustment is not 232 needed for comparison with the conceptual model (Fig. 1), and discrimination values are not 233 known for green turtles on these diets. 234 Statistical analyses 235 To test for annual differences in percent volume of diet items between 2008 and 2011, 236 ANOVA was used to compare between years and diet constituents. For 2011 samples, ANOVA 237 was used to compare between all samples (large+small) and only large samples and diet 238 constituents. A Tukey HSD multiple comparison test for unequal sample size was used when 239 significant differences were detected from the ANOVA. Volume percentages of diet items were 240 arcsine square root transformed to improve normality and homogeneity of variance. All data 241 were analyzed using program JMP version 9.0.2 (JMP®, 1989- 2010). 242 Results 243 In total, 43 stomach samples were analyzed from 2008 (n=12) and 2011 (n=31; volumes > 244 9.0ml). In 2008, CCL of turtles ranged from 23.6 to 35.9 cm (n=12; mean±SD=30.4±4.34). In 245 2011, CCL of turtles ranged from 22.5 to 72.7 cm (n=31; mean±SD=35.9±9.87) and body mass 246 ranged from 1.2 to 40.8 kg (n=31; mean±SD=6.73±6.93). Thirteen diet categories were 247 identified (Table 1): seagrass (n=3), algae (n=2), tunicate (n=2), and other materials (n=6). The 248 proportion of the tunicate Botrylloides sp. in the diet of green turtles differed significantly (P= 249 0.0037) between 2008 and 2011. Therefore, data from the two years were analyzed separately. In 250 the 2008 samples (n=12), three species were considered major diet items (>5% volume in at least 251 one sample; (Garnett et al., 1985), listed in order of importance: T. testudinum blades, 252 Botrylloides sp., and Pyrosoma sp. (Table 1). In the 2011 samples (n=31), six items were 253 considered major diet constituents, listed in order of importance: T. testudinum blades, Pyrosoma 254 sp., Botrylloides sp., Gracilaria sp., S. filiforme, and Enteromorpha sp. There was no significant 10 255 difference (seagrass P=0.2650; algae P=0.3637; tunicate P=0.6164; other materials P=0.4519) in 256 diet composition based on percent volume between all samples (large+small) and only large 257 samples in 2011 (Table 1), but the number of turtles with 100% volume of one diet species 258 declined from five to one. 259 In 2011, epidermis samples from 19 turtles were analyzed for stable isotope analyses. 260 Stable isotope values in epidermis tissue ranged from -15.6 to -8.1‰ for δ13C (mean±SD: - 261 12.9±2.0; Fig. 2). Epidermis δ15N values ranged from 7.4 to 11.6‰ (mean±SD: 9.1±1.2; Fig. 2). 262 Body size had a significant positive relationship with δ13C (R2 = 0.66, df = 38, p = < 0.001), but 263 no relationship with δ15N (p = 0.054). 264 Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope values were determined for six prey species: T. 265 testudinum, S. filiforme, H. wrightii, Gracilaria sp., Enteromorpha sp. and Botrylloides sp. (Fig. 266 2; Table 2). These prey species were considered primary diet constituents of green turtles based 267 on stomach contents. We were unable to apply mixing models to this study due to the inability to 268 locate Pyrosoma sp. during searches in fall 2011 and winter 2012 (see discussion). Individuals in 269 the population exhibited inconsistency in diet during the months before stomach samples were 270 collected (Fig. 2). The stable isotope value of the epidermis tissue was not associated with the 271 stable isotope value of the major diet item from the stomach contents. 272 Discussion 273 In the winters of 2008 and 2011, the diet of juvenile green turtles in St. Joseph Bay was 274 considered to be predominantly omnivorous. These results are similar to other studies conducted 275 in northwest Africa; Shark Bay, Australia; and San Diego Bay, California (Burkholder et al., 276 2011; Cardona et al., 2009; Lemons et al., 2011). Seagrass (T. testudinum) and tunicates 277 (Pyrosoma sp. and Botrylloides sp.) presented high IRI values in both years of this study. 11 278 The high degree of invertebrate consumption in this study highlights the importance of 279 quantifying the availability of animal prey and their nutritional contribution to green turtles. 280 Previous research (Davenport and Balazs, 1991) examined the nutritional content of Pyrosoma 281 atlanticum in leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) diets and found Pyrosoma bodies to be 282 composed of 27% protein, 3% lipid, and 70% carbohydrate. These tunicates may be targeted for 283 their ‘valuable’ stomachs, which contain digestible organic material, while the tunica may pass 284 through the gut relatively undigested (Davenport and Balazs, 1991). The digestibility of tunicates 285 such as Salpa and Pyrosoma spp. is not well known. It is possible that although tunicates provide 286 a high concentration of protein (Dubischar et al., 2012), the protein may be bound in compounds 287 not available to the turtle. Studies are needed that measure the digestibility and nutrient 288 availability of the many animal species ingested by green turtles to better understand their role as 289 a dietary component. 290 Stomach content analysis suggests a degree of among-individual variation, but isotope data 291 indicate no consistency within individuals over a few months. The wide distribution of13C 292 values results from turtles feeding on mixtures of seagrasses, algae and tunicates. Although we 293 were not able to collect samples of Pyrosoma sp., we believe they would have low 13C values 294 because they are pelagic organisms blown in from deeper waters of the Gulf of Mexico. 295 Stable isotope results indicate low consistency, which may be attributed to inconsistent 296 availability of seagrass and tunicates. Seasonal variation in seagrass biomass, algae biomass and 297 tunicate occurrence may lead to alternative feeding strategies. Although seagrass species are 298 present in SJB year round, there is a significant dieback of T. testudinum, H. wrightii, and S. 299 filiforme in shallow areas of the bay during winter. Previous investigations have found seagrass 300 production in SJB to be highly seasonal, with shoot biomass and density peaking during the 12 301 summer months (Iverson and Bittaker, 1986). Additionally, it appears that red algae coverage 302 increases in the fall months, then decreases during winter (pers. obs.). Pyrosoma are pelagic 303 species, known to form extensive, dense colonies that occur in irregular swarms (Andersen and 304 Sardou, 1994) throughout temperate waters. We believe green turtles in SJB fed on Pyrosoma 305 when they were carried into SJB by currents. Mass benthic deposition events of pyrosomids have 306 been recorded off the African coast (Lebrato and Jones, 2009). Previous studies have found 307 tunicates to be patchily distributed in the Gulf of Mexico (Graham, 2001). The other tunicate 308 species found in this study (Botrylloides sp.) is a benthic tunicate that grows on blades of T. 309 testudinum. These tunicates appear when water temperatures decrease (Sheri Johnson, pers. 310 comm.; pers. obs.). Green turtle digestive efficiency decreases with a decrease in water 311 temperature (Bjorndal, 1980), so during winter green turtles may select animal diet items which 312 are of higher digestibility. 313 This study also indicates that setting a minimum stomach sample size for gut content 314 analyses should be considered, especially with gastric lavage where samples tend to be small 315 (Nagaoka et al. 2012). Of the stomach samples in 2011 (n=49), three individuals had stomach 316 contents composed of 100% seagrass, two were 100% tunicates, and the remaining samples were 317 mixed diets of seagrass, tunicates and macroalgae. Although there were no significant 318 differences between all samples and only large samples in 2011, the number of turtles with 100% 319 seagrass or tunicates was greatly reduced from five samples to one sample after excluding small 320 sample volumes (<9.0 ml). Small, homogenous sample volumes may represent one feeding event 321 and give an unrealistic picture of diet. 322 323 In the present study, green turtles revealed flexible foraging strategies in the northern fringe of their year-round range. Prior to the 2008 and 2011 SJB cold stunning events, green 13 324 turtles in SJB were feeding as omnivores; however, prior to the cold stunning event in SJB in 325 2001, green turtles exhibited a herbivorous diet (Foley et al., 2007). Questions of feeding 326 consistency should be further examined by measuring seasonal and annual variation in prey 327 availability and selection. Future studies should address the relationship between diet selection, 328 digestive efficiency, and the nutritional value of animal matter in green turtle diets. 329 Understanding the temporal and geographic variation in sea turtle foraging ecology in peripheral 330 habitats, where they may be more susceptible to environmental changes, is necessary for 331 implementing effective, long-term conservation and management plans. 332 14 333 334 Acknowledgements We would like to express sincere thanks and appreciation to Dr. Jane Brockmann for her 335 creative assistance, support, and advice throughout the research and writing process. We thank L. 336 Avens, B. Stacy, A. Bolten, P. Eliazar, M. Frick, M. Lopez-Castro, M. Pajuelo, J. Pfaller, L. 337 Soares, H. Vander Zanden, and P. Zarate for project and creative assistance. J. Curtis of the 338 Stable Isotope Lab at the University of Florida assisted with stable isotope analyses. We thank S. 339 Farris, M. Pajuelo, and B. Stephens for the collection of stomach contents. We also thank the 340 many volunteers who assisted during the cold stunning events. The Sea Turtle Grants Program 341 (funded from proceeds from the sale of the Florida sea turtle license plate), Knight Vision 342 Foundation, and Jennings Scholarship funded this research. All project work was performed 343 under MTP # 094 and MTP # 016. Samples were collected and processed in compliance with 344 the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Florida. Any use of trade, 345 product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the 346 U.S. Government. 347 15 348 Literature cited 349 Andersen, V., Sardou, J., 1994. Pyrosoma atlanticum (Tunicata, Thaliacea) - Diel migration and 350 vertical distribution as a function of colony size. Journal of Plankton Research 16, 337- 351 349. 352 Avens, L., Goshe, L.R., Harms, C., Anderson, E., Goodman, A., Cluse, W., Godfrey, M., Braun- 353 McNeill, J., Stacy, B., Bailey, R., Lamont, M.M., 2012. Population characteristics, age 354 structure, and growth dynamics of neritic juvenile green turtles (Chelonia mydas) in the 355 northeastern Gulf of Mexico. Marine Ecology Progress Series 458, 213-229. 356 357 Bjorndal, K.A., 1980. Nutrition and grazing behavior of the green turtle, Chelonia mydas. Marine Biology 56, 147-154. 358 Bjorndal, K.A., 1985. Nutritional ecology of sea turtles. Copeia 1985, 736-751. 359 Bjorndal, K.A., 1997. Foraging ecology and nutrition of sea turtles, in: Lutz, P.L., Musick, J.A. 360 361 (Eds.), The biology of sea turtles. CRC Press, London, pp. 199-231. Bjorndal, K.A., Bolten, A.B., Lagueux, C.J., Jackson, D.R., 1997. Dietary overlap in three 362 sympatric congeneric freshwater turtles (Pseudemys) in Florida. Chelonian Conservation 363 and Biology 2, 430-433. 364 Bolten, A.B., 1999. Techniques for Measuring Sea Turtles, in: Eckert, K.L., Bjorndal, K.A., 365 Abreu-Grobois, F.A., Donnelly, M. (Eds.), Research and Management Techniques for the 366 Conservation of Sea Turtles. IUCN/SSC Marine Turtle Specialist Group Publication No. 367 4, pp. 110-114. 368 Bolten, A.B., 2003. Variation in sea turtle life history patterns: neritic vs. oceanic developmental 369 stages, in: Lutz, P., Musick, J., Wyneken, J. (Eds.), The biology of sea turtles, volume II. 370 CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, pp. 243-257. 16 371 372 Burke, V.J., Standora, E.A., Morreale, S.J., 1993. Diet of juvenile Kemp's ridley and loggerhead sea turtles from Long Island, New York. Copeia 1993, 1176-1180. 373 Burkholder, D.A., Heithaus, M.R., Thomson, J.A., Fourqurean, J.W., 2011. Diversity in trophic 374 interactions of green sea turtles Chelonia mydas on a relatively pristine coastal foraging 375 ground. Marine Ecology Progress Series 439, 277-293. 376 Cardona, L., Aguilar, A., Pazos, L., 2009. Delayed ontogenic dietary shift and high levels of 377 omnivory in green turtles (Chelonia mydas) from the NW coast of Africa. Marine 378 Biology 156, 1487-1495. 379 380 Coyne, M.S., 1994. Feeding ecology of subadult green sea turtles in south Texas waters. Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas. 381 Davenport, J., Balazs, G., 1991. 'Fiery bodies'- are pyrosomas an important component of the 382 diet of leatherback turtles? British Herpetological Society Bulletin 37, 33-38. 383 Dubischar, C.D., Pakhomov, E.A., von Harbou, L., Hunt, B.P.V., Bathmann, U.V., 2012. Salps 384 in the Lazarev Sea, Southern Ocean: II. Biochemical composition and potential prey 385 value. Marine Biology 159, 15-24. 386 Ferreira, M.M., 1968. On the feeding habits of the green turtle Chelonia mydas along the coast of 387 the state of Ceara. Arquivos da Estacao de Biologia Marinha da Universidade do Ceara 8, 388 83-86. 389 Foley, A.M., Singel, K.E., Dutton, P.H., Summers, T.M., Redlow, A.E., Lessman, J., 2007. 390 Characteristics of a green turtle (Chelonia mydas) assemblage in northwestern Florida 391 determined during a hypothermic stunning event. Gulf of Mexico Science 25, 131-143. 392 Fuentes, M.M.P.B., Lawler, I.R., Gyuris, E., 2006. Dietary preferences of juvenile green turtles 393 (Chelonia mydas) on a tropical reef flat. Wildlife Research 33, 671-678. 17 394 395 Garnett, S., Price, I., Scott, F., 1985. The diet of the green turtle, Chelonia mydas (L.), in Torres Strait. Wildlife Research 12, 103-112. 396 Graham, W.M., 2001. Numerical increases and distributional shifts of Chrysaora quinquecirrha 397 (Desor) and Aurelia aurita (Linne) (Cnidaria : Scyphozoa) in the northern Gulf of 398 Mexico. Hydrobiologia 451, 97-111. 399 Guebert-Bartholo, F.M., Barletta, M., Costa, M.F., Monteiro-Filho, E.L.A., 2011. Using gut 400 contents to assess foraging patterns of juvenile green turtles Chelonia mydas in the 401 Paranaguá Estuary, Brazil. Endangered Species Research 13, 131-143. 402 403 404 405 406 407 Hyslop, E.J., 1980. Stomach contents analysis—a review of methods and their application. Journal of Fish Biology 17, 411-429. Iverson, R.L., Bittaker, H.F., 1986. Seagrass distribution and abundance in Eastern Gulf of Mexico coastal waters. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 22, 577-602. Jacob, U., Mintenbeck, K., Brey, T., Knust, R., Beyer, K., 2005. Stable isotope food web studies: a case for standardized sample treatment. Marine Ecology Progress Series 287, 251-253. 408 JMP®, 1989- 2010. 9.0.2 ed. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC. 409 Lebrato, M., Jones, D.O.B., 2009. Mass deposition event of Pyrosoma atlanticum carcasses off 410 Ivory Coast (West Africa). Limnology and Oceanography 54, 1197-1209. 411 Lemons, G., Lewison, R., Komoroske, L., Gaos, A., Lai, C.-T., Dutton, P., Eguchi, T., LeRoux, 412 R., Seminoff, J.A., 2011. Trophic ecology of green sea turtles in a highly urbanized bay: 413 Insights from stable isotopes and mixing models. Journal of Experimental Marine 414 Biology and Ecology 405, 25-32. 18 415 Leonard, C.L., McClintock, J.B., 1999. The population dynamics of the brittlestar Ophioderma 416 brevispinum in near- and farshore seagrass habitats of Port Saint Joseph Bay, Florida. 417 Gulf of Mexico Science 17, 87-94. 418 López-Mendilaharsu, M., Gardner, S.C., Riosmena-Rodriguez, R., Seminoff, J.A., 2008. Diet 419 selection by immature green turtles (Chelonia mydas) at Bahía Magdalena foraging 420 ground in the Pacific Coast of the Baja California Peninsula, México. Journal of the 421 Marine Biological Association of the UK 88, 641-647. 422 McMichael, E., 2005. Ecology of juvenile green turtles, Chelonia mydas, at a temperate foraging 423 area in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico. University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, p. 95. 424 Mendonca, M.T., Ehrhart, L.M., 1982. Activity, population size and structure of immature 425 Chelonia mydas and Caretta caretta in Mosquito Lagoon, Florida. Copeia 1982, 161- 426 167. 427 Meylan, A.B., 1995. Sea turtle migration: Evidence from tag returns, in: Bjorndal, K.A. (Ed.), 428 Biology and conservation of sea turtles. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC, 429 pp. 91-100. 430 431 432 433 434 Morreale, S.J., Meylan, A.B., Sadove, S.S., Standora, E.A., 1992. Annual occurrence and winter mortality of marine turtles in New York waters. Journal of Herpetology 26, 301-308. Mortimer, J.A., 1981. The feeding ecology of the west Caribbean green turtle (Chelonia mydas) in Nicaragua. Biotropica 13, 49-58. Nagaoka, S.M., Martins, A.S., Santos, R.G., Tognella, M.M.P., Oliveira Filho, E.C., Seminoff, 435 J.A., 2012. Diet of juvenile green turtles (Chelonia mydas) associating with artisanal 436 fishing traps in a subtropical estuary in Brazil. Marine Biology 159, 573-581. 19 437 438 439 Preserves, C.P.A., 2008. The St. Joseph Bay Aquatic Preserve Management Plan 2008-2018. Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Apalachicola, FL. Schwartz, F.J., 1978. Behavioral and tolerance responses to cold water temperatures by three 440 species of sea turtles (Reptilia, Cheloniidae) in North Carolina. Florida Marine Research 441 Publications 33, 16-18. 442 Seminoff, J.A., Jones, T.T., Eguchi, T., Jones, D.R., Dutton, P.H., 2006. Stable isotope 443 discrimination (13C and 15N) between soft tissues of the green sea turtle Chelonia mydas 444 and its diet. Marine Ecology Progress Series 308, 271-278. 445 446 447 Stewart, R.A., Gorsline, D.S., 1962. Recent sedimentary history of St. Joseph Bay, Florida. Sedimentology 1, 256-286. Vander Zanden, H.B., K.A. Bjorndal, K.J. Reich, and A.B. Bolten. 2010. Individual specialists in 448 a generalist population: results from a long-term stable isotope series. Biology Letters 449 6:711-714. 450 Vander Zanden, H.B., K.A. Bjorndal, and A.B. Bolten. In press. Temporal consistency and 451 individual specialization in resource use by green turtles in successive life stages. 452 Oecologia. 453 454 Witherington, B.E., Ehrhart, L.M., 1989. Hypothermic stunning and mortality of marine turtles in the Indian River Lagoon system, Florida. Copeia 1989, 696-703. 455 456 457 20 458 459 460 Figure legends 461 representing (a) inconsistent resource use through time and (b) consistent resource use through 462 time. Closed symbols represent prey items; open symbols represent individual turtles. See text 463 for discussion of model Fig. 1 Conceptual model of patterns of isotope values for carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) 464 465 Fig. 2 Chelonia mydas. Plot of stable isotope ratios of nitrogen and carbon from epidermis 466 samples and major prey items of juvenile green turtles. Closed symbols represent prey items; 467 open symbols represent individual turtles categorized by their primary diet item. Prey items are 468 shown as mean (standard deviation) 21 Table 1 Chelonia mydas. Diet composition of juvenile green turtles in St. Joseph Bay, Florida Prey item % Volume (ml) mean (SD) % Dry Mass (g) mean (SD) IRI %F 2008 2011 2011 ALL 2008 2011 2011 ALL 2008 2011 2011 ALL 2008 2011 2011 ALL n=12 n=31 n=49 n=12 n=31 n=49 n=12 n=31 n =49 n=12 n =31 n=49 T. t. blades 22.8 (11.9) 12.2 (10.7) 7.8 (9.8) 2.30 (1.28) 1.14 (1.02) 0.7 (0.94) 74.40 70.14 70.33 100 100 93.88 T. t. rhizome 0.4 (1.2) 0.1 (0.5) 0.1 (0.4) 0.03 (0.09) 0.02 (0.06) 0.01 (0.05) 0.21 0.13 0.11 16.67 16.13 12.24 H. wrightii 0.1 (0.4) 0.0 0.1 (0.3) 0.01 (0.03) 0.01 (0.01) 0 (0.02) 0.03 0.02 0.05 8.33 12.9 10.20 S. filiforme 0.0 1.8 (9.0) 1.2 (6.9) 0.00 0.08 (0.37) 0.05 (0.28) 0.00 0.65 0.66 0.00 6.45 6.12 Gracilaria sp. 0.0 0.6 (3.1) 0.6 (2.5) 0.00 0.03 (0.12) 0.02 (0.10) 0.01 0.22 0.66 0.00 6.45 12.25 Enteromorpha 0.0 0.9 (3.3) 0.5 (2.6) 0.00 0.01 (0.07) 0.01 (0.05) 0.00 0.49 0.30 0.00 9.68 6.12 Pyrosoma sp. 3.5 (2.7) 5.1 (4.9) 3.2 (4.3) 0.23 (0.39) 0.19 (0.21) 0.13 (0.19) 11.40 26.70 26.70 100 90.32 83.67 Botrylloides sp. 5.7 (7.0) 0.6 (1.1) 0.3 (0.9) 0.27 (0.35) 0.04 (0.07) 0.02 (0.05) 14.00 1.66 1.20 75 45.16 32.65 feather 0.0 tr tr tr tr tr 0.00 tr tr 0.00 tr tr UM 0.0 tr tr 0.00 tr tr 0.00 tr tr 0.00 tr tr plastic 0.0 tr tr 0.00 tr tr 0.00 tr tr 0.00 3.23 2.04 shell 0.0 tr tr tr tr tr 0.00 tr tr 0.00 tr tr UPM 0.0 tr tr 0.00 tr tr 0.00 tr tr 0.00 tr tr Seagrasses Macroalgae sp. Tunicates Other materials Percent volume, percent dry mass, index of relative importance (IRI), and frequency of occurrence (% F) for green turtles from cold stunning events in St. Joseph Bay, Florida, in January 2008 and 2011. “ALL” refers to both small and large volumes of stomach contents from 2011; 2011 includes only large volumes ( > 9.0 ml). “tr” refers to trace. Values are presented as mean (SD). UM: unidentified material; UPM: unidentified plant material; T.t.: Thalassia testudinum. 22 Table 2 Chelonia mydas. Mean stable isotope values of prey items and green turtle epidermis. Prey values are presented as mean (range) and epidermis values as mean (standard deviation) Prey item N d13C (‰) d15N (‰) Seagrasses H. wrightii 2 -11.4 (-11.38 to -11.40) 1.4 (1.22 to 1.53) S. filiforme 2 -6.9 (-6.88 to -6.97) 4.1 (4.01 to 4.16) T. testudinum 2 -6.8 (-6.75 to -6.86) 5.6 (5.56 to 5.57) Macroalgae Gracilaria sp. 2 -13.0 (-12.9 to 13.14) 6.6 (6.05 to 6.76) Enteromorpha sp. 2 -12.8 (-12.72 to -12.78) 5.5 (5.51 to 5.56) Tunicates Botrylloides sp. 2 -16.1 (-16.11 to -16.20) 5.1 (5.04 to 5.22) Green turtles 19 -12.9 (2.0) 9.1 (1.2) 23 Macroalgae (a) Seagrasses Tunicates 15 N (‰) 13 C (‰) (b) 15 N (‰) 13 C (‰) 24 14 Tunicates Macroalgae Seagrasses > 50 % tunicates > 50 % macroalgae > 50 % seagrasses 12 15N (‰) 10 8 6 4 2 0 -18 -16 -14 -12 -10 13C (‰) 25 -8 -6 -4