Final Version Thesis

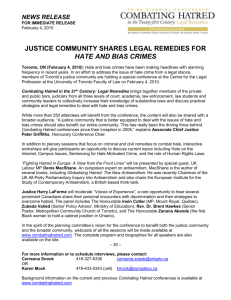

advertisement