The Weedy Facts

advertisement

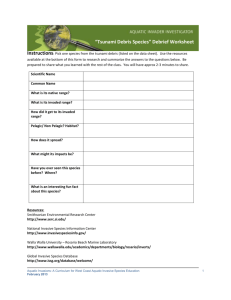

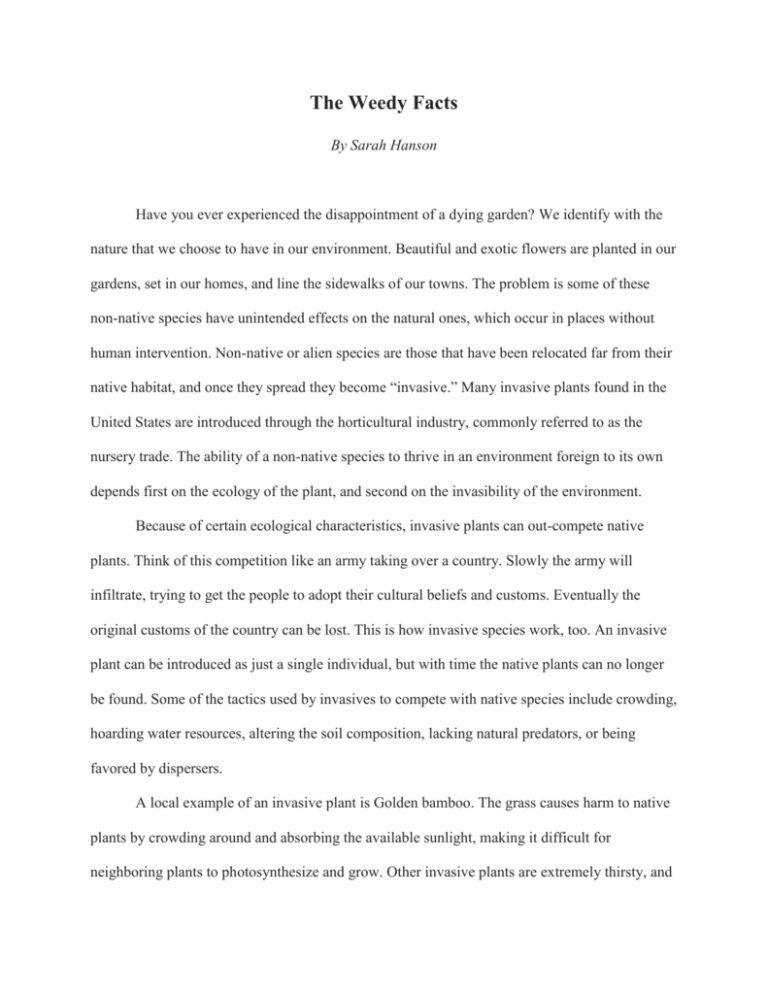

The Weedy Facts By Sarah Hanson Have you ever experienced the disappointment of a dying garden? We identify with the nature that we choose to have in our environment. Beautiful and exotic flowers are planted in our gardens, set in our homes, and line the sidewalks of our towns. The problem is some of these non-native species have unintended effects on the natural ones, which occur in places without human intervention. Non-native or alien species are those that have been relocated far from their native habitat, and once they spread they become “invasive.” Many invasive plants found in the United States are introduced through the horticultural industry, commonly referred to as the nursery trade. The ability of a non-native species to thrive in an environment foreign to its own depends first on the ecology of the plant, and second on the invasibility of the environment. Because of certain ecological characteristics, invasive plants can out-compete native plants. Think of this competition like an army taking over a country. Slowly the army will infiltrate, trying to get the people to adopt their cultural beliefs and customs. Eventually the original customs of the country can be lost. This is how invasive species work, too. An invasive plant can be introduced as just a single individual, but with time the native plants can no longer be found. Some of the tactics used by invasives to compete with native species include crowding, hoarding water resources, altering the soil composition, lacking natural predators, or being favored by dispersers. A local example of an invasive plant is Golden bamboo. The grass causes harm to native plants by crowding around and absorbing the available sunlight, making it difficult for neighboring plants to photosynthesize and grow. Other invasive plants are extremely thirsty, and Hanson 2 manage to drink most of the water. A great example of this type of invasive is the eucalyptus tree found throughout South Africa. Phyllostachys aurea (Golden bamboo) Eucalyptus grandis (Flooded gum) In the late nineteenth century, the trees were planted by the thousands to be used by the booming gold mining industry as walls to their mines. Two centuries after their introduction, an initiative was launched by the Working for Water foundation to have the trees removed: not only did they deplete all of the ground water, but they were also allelopathic, which means that the trees were able to inject a chemical into the soil that caused native plants to become ill. Natural regulatory controls, such as herbivores or pests, that would keep the growth of these invasive species in check in a native setting, are often absent in the introduced environment, so plants can spread at an extremely fast pace in comparison to their natural environment. Unfortunately, while pests and insects commonly avoid feeding on non-native plants, birds and mammals often do consume their fruit. Fleshy fruited invasive plants have the highest potential to spread and outcompete native ones because in addition to wind and water, they have animals to spread their seeds. If an animal or pollinator favors the invasive flower or fruit, a native plant becomes ignored. When the animals change their diet, from native to invasive, often the native species is eradicated altogether. Hanson 3 But what makes an environment so unfit for native species and so welcoming for invasive species? Simply put, some environments are more invasible than others. Generally, environments that lack human activities such as roadways are not heavily overturned or harvested and are least at risk for biological invasions. The most invasible environments are those that have an altered state of physical landform, vegetation, and hydrology, creating bare soil, erosion, or sedimentation. Once land is disturbed, soil, sunlight, water, and other nutrients become readily available to the invasive that can enjoys freedom from competition with native species and can take root rather quickly. Another factor that makes an environment invasible is a gap. Often the species that are most successful to filling these open niches are those that are non-native, as native plants are less successful in exploiting the open areas. Like grilled stickies and vanilla ice cream, sometimes an invasive’s ecology and the foreign environment are extremely compatible. In South Africa, for example, there is a small Nature Reserve called Dwesa-Cwebe. The coastal reserve is extremely diverse in plant and animal species, but can be considered an extremely disturbed place, because located within its boundaries is a hotel. To better suit the guests’ needs in the early nineteenth century, a garden was planted near the shore and was planted with bananas, avocado, and guava fruit. Today, the garden is overgrown with grass and no longer produces bananas or avocado, but the guava remains abundant. The guava’s success in comparison to the banana and avocado trees can be attributed to the production of viable seeds as well as its tolerance to various environmental conditions. The guava is now listed in the Global Invasive Species Database as a fierce invader in regions of Hawaii and the Galapagos Islands, in addition to southern Africa. The small baseball-sized fruits have an extremely seedy center, as seen in Figure 1. Hanson 4 Figure 1: Psidium guajava (Common guava) It takes only three years for them to mature from a seedling to a fruit-producing adult. The shrub is widely tolerant of drought, sea spray, and can grow in nearly any soil type. Monkeys, birds, cattle, and humans can be seen munching on the fruit, and the seeds have been excreted nearly everywhere. Roadways are particularly important in the discussion of invasive species like the guava for several reasons. First, tire treads are great at carrying and depositing seeds. Second, roadways must be laid on top of the earth’s surface, causing sediment to be removed and regularly tossed around. Third, birds and small mammals like the vervet monkey, which are abundant in DwesaCwebe, prefer to hangout along forest edges. The presence of a roadway divides a forest into parts and causes animals to come to the outskirts. Finally, roadways aid in the establishment of invasive plants because of the power lines that often trace their course. Power lines are a preferred perching location for birds, and as a result thousands of guava seeds have been excreted by birds directly above the overturned soil causing the shrub to spread like wildfire along the forest edges. Like citrus fruits, the guava shrubs require sunlight to grow and will not be found growing in forest interiors. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the guava shrub along the roadways in the Dwesa-Cwebe Nature Reserve. Hanson 5 Hotel Historic Garden Guava Figure 2: Visualization of invasive guava distribution at the intersection of two roadways in the Dwesa-Cwebe Nature Reserve. Credit: Sarah L. Hanson, Department of Geography, The Pennsylvania State University. Google Earth. You can notice that the guava is most abundant near the hotel and the intersection of two roadways, and becomes less prevalent as distance increases from the site of introduction, the historic garden. Not much is understood about the affects the shrub has on native species, and no action is being taken by conservationists against the shrub to date. Like many weeds, when the shrub is cut several grow back in its place, making it extremely difficult to control. One thing is for sure though: the shrub is spreading as fast as water runs rapid, and will inevitably cause the decline of natural plant species. Hanson 6 Environments are constantly changing as new species are introduced and others are removed. Plants and animals are continually adapting to avoid being outcompeted, but many times invasive species have the upper hand and can affect the ecology of an area before actions are made to prevent the change. So the next time you are at the local nursery, you should make informed decisions about the types of plants you are choosing for your garden, and recognize that your desire to shape your environment can have a broader impact. Hanson 7 Special Thanks to: Dr. Erica Smithwick, Director of Landscape Ecology at Penn State (LEAPS) Ms. Del Bright, Giles-in-Residence Writer About the Author Sarah Hanson is a senior majoring in Geography pursuing two minors in Geographic Information Science (GIS) and the Science, Society, and Environment of Africa. Sarah studied in South Africa on a faculty-led program called Parks and People in 2011, and was able to return the following year to Dr. Erica Smithwick with her research. In June of 2012, Sarah was able to assist Dr. Blair Hedges in surveying the remaining biodiversity of Haiti’s reptiles and amphibians and she currently works with Dr. Hedges on the molecular timescale and evolutionary history of life database known as TimeTree.org. After graduation, Sarah plans to earn an advanced degree in geography, forestry, or photo journalism. Hanson 8 Works Cited Bargeron, Chuck. “Golden Bamboo.” Photo. Ipmimages.org 17 Nov. 2003. 15 Feb. 2013. < http://www.ipmimages.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=1237039>. “Fazenda em Agudos.” Photo. Flickr.com 04 May 2010. 15 Feb. 2013. < http://www.flickr.com/photos/psicodrops/4609098972/in/photostream/>. Henderson, Scott. "Ecology of Psidium Guajava." Global Invasive Species Database. 10 Aug. 2010. Web. 17 Jan. 2013. <http://www.issg.org/database/species/ecology.asp?si=211>. “Mighty Guava.” Photo. Super Human Foods.org 16 June 2012. 10 Oct. 2012. <http://superhumanfoods.org>.