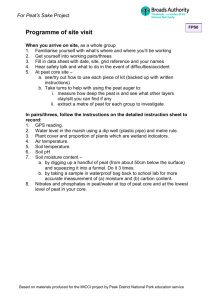

The Carbon and Water Guidelines

advertisement