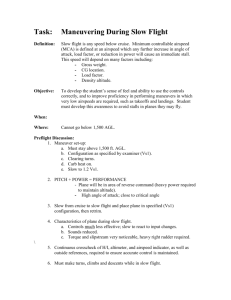

XI-A-Slow-Flight - Leading Edge Flying Club

advertisement

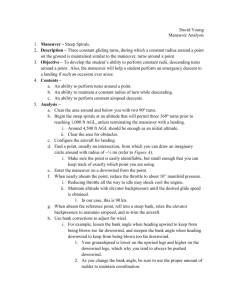

David Young Maneuver Analysis Maneuver – Slow Flight. Description – Maneuvering the aircraft in the region of reverse command. Objective – To develop the student’s sense of feel while flying at slow airspeeds. Contents – a. The ability to perform level turns in an aircraft. b. The ability to perform climbs and descents. c. The ability to maintain a constant heading. d. The ability to maintain altitude. e. A basic understanding of how to interpret the airspeed indicator, attitude indicator, VSI, altimeter, and directional gyro. f. An understanding of drag and its effects on the handling of the aircraft. g. An understanding of the importance of “pitch for airspeed, power for altitude.” h. The ability to maneuver the aircraft in a specified configuration. 5. Analysis – a. Refer to Figure A (attached). i. As airspeed decreases from cruise to the max ratio of lift to drag, the amount of thrust required decreases. ii. As airspeed further decreases from the L/Dmax, the amount of thrust required to maintain altitude increases, and this is known as the region of reverse command. 1. This means that more, not less, power is required to maintain altitude at slower airspeeds. b. Perform two clearing turns (two 90º turns) to clear the area around you. c. To enter slow flight, retard the throttle to a lower setting. Lower the landing gear when below Vle to help slow the aircraft down. i. Initially reduce the throttle to about 1,600 RPM. d. When below Vfe, begin extending flaps until all flaps are extended (or whatever is specified by the POH or examiner) while continually maintaining altitude. i. This will require more and more elevator backpressure to compensate for the reduction in airspeed, which results in a decrease in lift. e. As the aircraft slows down to Vso, increase power to about 2,000 RPM to keep the aircraft at what is called Vmca or minimum controllable airspeed. i. This is the minimum airspeed at which the aircraft can be positively controlled. It usually occurs as the stall horn comes on, but before the aircraft stalls. ii. ALWAYS KEEP YOUR HAND ON THE THROTTLE. f. Re-trim the aircraft to maintain altitude. g. It is extremely important to pitch for airspeed, and use power to control altitude. 1. 2. 3. 4. Young 2, XI-A h. i. j. k. l. m. n. o. i. If pitch is used to control altitude, then, if the aircraft begins to descend and the pilot pitches up, the aircraft will stall. If power is used instead, the aircraft will keep flying. 1. A stall is simply when there is not enough lift to keep the aircraft flying. Use smooth, although larger, control movements to maintain straight and level flight. i. Larger inputs are needed because, as the airflow over the control surfaces decreases, the control surfaces become less effective. If the aircraft begins to bank towards one side or another, “step on the high wing,” or press the rudder pedal on the side of the high wing. Do NOT solely use ailerons to maintain wings level. i. This, along with keeping the ball centered, should keep the plane from entering a spin if a stall is inadvertently encountered. When turning, the pitch attitude and power must be increased in order to maintain airspeed and altitude. i. The bank angle should remain very shallow because the vertical component of lift needs to be as great as possible, and when angle of bank increases, the vertical component of lift decreases. If asked to perform a climb, add power to begin the climb and simultaneously increase the pitch attitude to maintain airspeed. i. Note that the vertical speed will probably be lower than a normal climb. If asked to perform a descent, reduce power to begin the descent and simultaneously decrease the pitch attitude to maintain airspeed. To recover, add full power and immediately take off one notch of flaps once the airspeed is above Vs1. i. Note that the pitch attitude must be reduced to maintain altitude with the increase in power and, eventually, airspeed. 1. Therefore, relieve some of the elevator backpressure. ii. Note that considerable right rudder will be needed to counteract the left turning tendencies of the aircraft when full power is applied. iii. Note that the use of lots of nose-up trim to maintain altitude during slow flight will cause the plane to want to climb when power is added. Immediately put in some nose-down trim, and once recovered, re-trim the aircraft. Eventually take off the rest of the flaps, raise the landing gear, accelerate to cruise speed, then adjust the throttle for cruise flight. Re-trim the aircraft. Young 3, XI-A p. If a stall is inadvertently encountered, pitch down while simultaneously applying full power. Use some right rudder to stay coordinated, and take off one notch of flaps. i. Begin to pitch up smoothly to begin climbing again, but be VERY careful not to enter a secondary stall by pitching up too much. ii. When the VSI indicates a positive rate, take the second notch of flaps off, and finally, take the last notch off when at Vy. 6. Visual Cues – a. Use the engine cowling and the horizon to determine the level flight pitch attitude. b. As airspeed decreases, the horizon will move further and further down the cowling. c. During the recovery, the horizon will move further and further up the cowling. d. The wings should remain level, and, therefore, the horizon should cut straight through the cowling unless asked to perform a turn. 7. Instrument Cues – a. Use the attitude indicator to determine level flight. b. The directional gyro will tell you if you have strayed off course. c. The altimeter should remain motionless the entire time unless performing a climb or descent while in slow flight. d. The ball will swing to the right side of the inclinometer during the recovery from slow flight. e. If the altimeter indicates a climb, reduce the throttle to descend. Then bump in a little extra power to maintain altitude. f. If the altimeter indicates a descent, increase the throttle to climb. Then take out a little power to maintain altitude. 8. PTS Standards – a. Private Pilot – i. Exhibits knowledge of the elements related to maneuvering during slow flight. ii. Selects an entry altitude that will allow the task to be completed no lower than 1,500 feet (460 meters) AGL. iii. Establishes and maintains an airspeed at which any further increase in angle of attack, increase in load factor, or reduction in power, would result in an immediate stall. iv. Accomplishes coordinated straight-and-level flight, turns, climbs, and descents with landing gear and flap configurations specified by the examiner. v. Divides attention between airplane control and orientation. vi. Maintains the specified altitude, ±100 feet (30 meters); specified heading, ±10°; airspeed, +10/−0 knots; and specified angle of bank, ±10°. b. Commercial Pilot – Young 4, XI-A i. Exhibits knowledge of the elements related to maneuvering during slow flight. ii. Selects an entry altitude that will allow the task to be completed no lower than 1,500 feet (460 meters) AGL. iii. Establishes and maintains an airspeed at which any further increase in angle of attack, increase in load factor, or reduction in power, would result in an immediate stall. iv. Accomplishes coordinated straight-and-level flight, turns, climbs, and descents with landing gear and flap configurations specified by the examiner. v. Divides attention between airplane control and orientation. vi. Maintains the specified altitude, ±50 feet (15 meters); specified heading, ±10°; airspeed +5/−0 knots, and specified angle of bank, ±5°. 9. Common Errors – a. Failure to establish proper gear and flap configuration. b. Improper entry technique. c. Failure to establish and maintain airspeed and altitude. d. Uncoordinated flight. e. Unintentional stalls. f. Removing the hand from the throttle. 10. References – a. AFH, Ch. 5 b. Gleim’s Flight Instructor Flight Maneuvers, Part II, Unit XI c. FAA-S-8081-12B d. FAA-S-8081-14A Young 5, XI-A Figure A