Bailyn - CLAS Users

advertisement

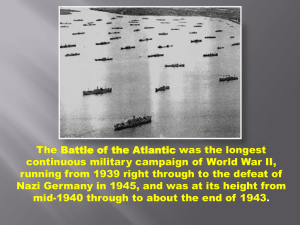

Delvaux 1 of 4 Bernard Bailyn and Atlantic History Matthew Delvaux 23 January 2012 Bernard Bailyn (born 1922) completed undergraduate studies at Williams College and graduate studies at Harvard University. He submitted his dissertation in 1953 and continued teaching at Harvard. He received full professorship there in 1961 and has continued as professor emeritus since 1993. He remains as the director of the International Seminar on the History of the Atlantic World, 1500-1825. During his long and prolific career, Bailyn has exerted profound influence on early American and Atlantic historiography. His work has focused on settlement, commerce, society and politics in seventeenth and eighteenth century America. Among his many accomplishments, Bailyn has received two Pulitzer prizes and served as president of the American Historical Association (1981).1 According to Peter A. Coclanis, “he is, along with Edmund S. Morgan and Jack P. Greene, part of ‘the gang of three’ that has led, inspired, and, through intellectual force, institutional authority, and bevies of talented academic progeny dominated early American history over the past half century.”2 Coclanis’s identification of Bailyn, Morgan and Greene as the foundational scholars of Atlantic history should not suggest that these scholars worked in concert toward a common intellectual goal. Indeed, two of Bailyn’s most important monographs, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (1967) and The Origins of American Politics (1968), provoked harsh criticism from Greene, resulting in a dispute published in The American Historical Review.3 Bailyn’s influence on and place in Atlantic history should rather be explored through his 1996 article “The Idea of Atlantic History.”4 He republished this article substantively unchanged in 2005 along with a companion article “On the Contours of Atlantic History” in Atlantic History: Concept and Contours.5 In both publications, he argues that Atlantic history did not develop (1) in imitation of Fernand Braudel, (2) simply as an expansion of “imperial” history, nor (3) from works in the fields of exploration and “About Bernard Bailyn” [online], International Seminar on the History of the Atlantic World,1500-1825 (Harvard: site created 16 January 1998; last revised 24 February 2011), accessed 20 January 2012; available from http://www.fas.harvard.edu/~atlantic/index.htm. 2 Peter A. Coclanis, “Drang Nach Osten: Bernard Bailyn, the World-Island, and the Idea of Atlantic History,” Journal of World History 13, No. 1 (Spring, 2002): 170. 3 Jack Greene, “Political Mimesis: A Consideration of the Historical and Cultural Roots of Legislative Behavior in the British Colonies in the Eighteenth Century,” AHA 75, no. 2 (Dec. 1969): 337-360. Bernard Bailyn, “A Comment,” AHA 75, no. 2: 361-363. Greene, “Reply,” AHA 75, no. 2: 364-367. 4 Bailyn, “The Idea of Atlantic History,” Itineraria 20 (1996): 19-44. 5 Bailyn, Atlantic History: Concept and Contours (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005). 1 Delvaux 2 of 4 discovery.6 Instead, Bailyn argues that Atlantic history developed at least in part “because the public context of our lives has expanded since World War II,” although he traces this expansion back to the first expression of an “Atlantic Community” given by Walter Lippmann in 1917. 7 Nevertheless, Bailyn’s version of the Atlantic remains deeply rooted in Braudel’s 1949 publication of The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. Bailyn was highly critical of this work, which was published in the midst of his doctoral studies. While still a student, he published a scathing review in the Summer 1951 edition of The Journal of Economic History.8 In this article, he summarizes the three rhythmic cycles of time which Braudel uses to organize his work: The first aspect of this “world” is geographic: “man in his relations with the environment that surrounds him” (p. xiii). Here the significant movement is almost imperceptible and is complicated by the ceaselessly revolving inner cycles of seasons and years. Its “time” is that of geography (p. xiv). The second aspect is that usually dealt with by social and economic historians: the histories “of the groups, of the structures, of the collective destinies, in a word, of the group movements” (des movements d'ensemble) (p. 308). Here the motion is “slowly rhythmed” (lentement rhythmée), and the time may be called “social.” … The third element is that usually dealt with by the traditional historians: the “short, quick, nervous oscillations” of men of action.9 This approach strikes Bailyn as “original and illuminating” where these three aspects are allowed to mingle, but Braudel interrupts such analysis by compartmentalizing each aspect to its own subdivision within the text: “What is painfully lacking in this huge, rambling book is the integration of its parts that could result from the posing of proper historical questions. In place of this, one finds an attempt to tell all, to investigate every cranny of the Mediterranean periphery, and to call in the witness of the allied social sciences.”10 It is important to dwell upon this article because Bailyn—just as he is beginning to establish himself as a scholar—thus uses Braudel as a foil for examining the purpose and process of history. Bailyn concludes, “if it is to fulfill its function of making man's past intelligible, history must remain the empirical study of the process of human affairs.”11 And therefore in practice, Bailyn suggests, “A proper formulation would have started with a broad and important movement in the affairs of men living in this time and area, and on the hooks of this movement Bailyn, “Idea”: 20-21. Ibid.: 41, 21. 8 Bailyn, “Braudel’s Geohistory—A Reconsideration,” The Journal of Economic History 11, no. 3, part 1 (Summer, 1951): 277-282. 9 Ibid.: 278-279. 10 Ibid.: 279, 281. 11 Ibid.: 282. 6 7 Delvaux 3 of 4 elements from every aspect and level of this ‘world’ would have been drawn together to form a satisfactory and hence complex and subtle answer.”12 This emphasis on formulaic historical problems and synthetic integration of time and area has shaped Bailyn’s career. His first monograph, a revision of his dissertation, appeared in 1955: The New England Merchants in the Seventeenth Century. His subsequent publications likewise focus on “early American history, the American Revolution, and the Anglo-American world in the pre-industrial era.”13 His research does not follow in the unifying spatial footsteps of Braudel but instead uses the Atlantic as a dynamic tool. Fellow Atlantic historian Alison Games describes Bailyn as “rejecting the region as a ‘static historical unit’ and emphasizing instead the mobility of the region, not only its shifting cast of characters but also its networks and relations of power.”14 However she notes with dissatisfaction that the problems Bailyn addresses in Atlantic History: Concepts and Contours focus his attention on Europe and the American mainland. As a result, he falls short of describing the horizons Atlantic history as she conceives them, claiming Bailyn’s text “looks like colonial histories writ large.”15 In an ironic twist, Bailyn is now faulted near the end of his career for failing to achieve that which he faulted in others at the start of his career. As Bailyn criticized Braudel’s attempt “to investigate every cranny of the Mediterranean periphery,”16 Games conversely criticizes Bailyn’s “reluctance to assimilate Africa and Africans as full participants in all aspects of the Atlantic.” 17 Likewise, Coclanis views Bailyn as too provincial, although his criticism lands upon Atlantic history as a whole: By fixing our historical gaze so firmly toward the West, the approach may, anachronistically, give too much weight to the Atlantic Rim, separate Northwest Europe too sharply both from other parts of Europe and from Eurasia as a whole, accord too much primacy to America in explaining Europe's transoceanic trade patterns, and, economically speaking, misrepresent through overstatement the place of Europe in the order of things.18 Although it is tempting to identify Bailyn as a foundational Atlantic scholar, such criticisms serve to remind us that his Atlantic history is but an Atlantic history, and his works are better critiqued by the questions they ask rather than the regions they question. Ibid.: 281. “About Bernard Bailyn” [online]. 14 Alison Games, Review: Atlantic History: Concept and Contours by Bernard Bailyn, American Historical Review 111, No. 2 (April 2006): 434. 15 Ibid. 16 Bailyn, “Braudel”: 281. 17 Games: 435. 18 Coclanis: 176. 12 13 Delvaux 4 of 4 Selected Works Books: The New England Merchants in the Seventeenth Century (1955) Massachusetts Shipping, 1697-1714 (with Lotte Bailyn 1959) Education in the Forming of American Society (1960) editor Pamphlets of the American Revolution (1965) ed. The Apologia of Robert Keayne (1965) The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (1967) (received Pulitzer and Bancroft Prizes in 1968) The Origins of American Politics (1968) co-editor The Intellectual Migration, Europe and America, 1930-1960 (1969) co-ed. Law in American History (1972) The Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson (1974) (received National Book Award in History in 1975) The Great Republic (with Robert Dallek, David Davis and David Donald 1977) co-ed. The Press and the American Revolution (1980) The Peopling of British North America: An Introduction (1986) Voyagers to the West (1986) (received Pulitzer Prize) Faces of Revolution (1990) co-ed. Strangers within the Realm: Cultural Margins of the First British Empire (1991) ed. Debate on the Constitution (1993) On the Teaching and Writing of History (1994) To Begin the World Anew (2003) Atlantic History: Concept and Contours (2005) co-ed. Soundings in Atlantic History: Latent Structures and Intellectual Currents, 1500-1830 (2009) Articles: “The Apologia of Robert Keayne,” The William and Mary Quarterly (Oct. 1950) “Braudel's Geohistory—A Reconsideration,” The Journal of Economic History (Summer 1951) “Communications and Trade: The Atlantic in the 17th Century,” Economic History (Autumn 1953) “England's Cultural Provinces: Scotland & America” (with John Clive), William & Mary (Apr. 1954) “Political Experience and Enlightenment Ideas in Eighteenth-Century America,” AHA (Jan. 1962) “Butterfield's Adams: Notes for a Sketch,” William & Mary (Apr. 1962) “A Comment,” AHA (Dec. 1969) “The Index and Commentaries of Harbottle Dorr,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society (1973) “1776 A Year of Challenge—A World Transformed,” Journal of Law and Economics (Oct. 1976) “1776: The British Dimension,” Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London (Jan., 1977) “Morison: An Appreciation,” Massachusetts Historical Society (1977) “The American Academy & American Society,” Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences (Dec. 1980) “The Challenge of Modern Historiography,” AHA (Feb. 1982) “Reflections on the Founding of Williams College” (with six others), Massachusetts Historical Society (1993) “Jefferson and the Ambiguities of Freedom,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society (Dec. 1993) “In Celebration: The 220th Anniversary of the Academy” (with four others), Arts & Sciences (Autumn 2000) “Considering the Slave Trade: History and Memory,”William & Mary (Jan. 2001) “Franklin L. Ford 26 December 1920 · 31 August 2003,” (with four others), Mass. Historical Society (Dec. 2008)