I-News_LosingGround-National_Mainbar

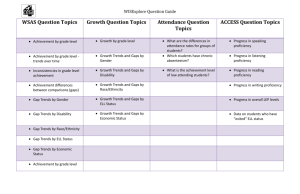

advertisement

NATIONAL GAPS By BURT HUBBARD I-News Network By some of the most important measures of social progress, black and Latino residents of the United States have lost ground as compared to the nation’s white residents in the decades since the civil rights movement. Some gains made by the nation’s two largest minority groups during the 1960s and 1970s have eroded with time, an analysis of six decades of demographic data from the U. S. Census Bureau found. In other categories, the gaps between whites and minorities have steadily widened since 1960. The analysis, undertaken by I-News, the public service journalism arm of Rocky Mountain PBS, focused on family income, poverty rates, high school and college graduation and home ownership. Apart from the Census data, health and justice records examined also revealed stark inequities. According to most experts, racial and ethnic inequality will pose a significant future handicap for a nation in which minorities are the fastest rising population. “I was actually shocked,” said Eric Nelson, a Colorado NAACP official, after examining the I-News analysis. “You would think we as a nation would have overcome a lot of things since then. It’s like, ‘Wow! We’re spinning our wheels going in reverse.’ ” Latino and black families nationally earn only about 60 percent of white family incomes today, the analysis found. Latino adults graduate from college at less than half of the rate of white adults with black adults lagging almost as much. Both groups are generally twice as likely to live in poverty. Less than half of minority households own their own homes compared to almost three-fourths of white households. “The idea that has been propagated by proponents of civil rights and kind of accepted by the white majority was, ‘We did it. There were a lot of problems. Martin Luther King made a speech and we enacted some laws and it’s OK now,’ ” said Gary Orfield, co-director of the Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Law. “That’s just not true. We didn’t do it.” There are important caveats, of course, including the rise of professional classes among both blacks and Latinos and striking examples of individual wealth and achievement. Minorities have made gains in a number of categories, as well, but in most have not kept pace with their white counterparts. By the broad gauge of the census measures, recent decades have not been kind to aspirations of equality by the nation’s Latino and black residents. Almost 50 years after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his generation defining “I have a dream” speech, income and education gaps remain stubbornly high. The Census partitions the country into four broad regions – Northeast, South, Midwest and West – with nine sub-regions, and the I-News analysis shows the ethnic and racial inequities fluctuating by region during the past decades. Most recently, some of the largest widening of the gaps has emerged in the Midwest, while minority gains, especially among African Americans, are most evident in the South. I-News reviewed six decades worth of census data from 1960 to 2010, nationally and among all 50 states. Among the findings: Gains made by black households nationally between 1960 and 1980 in narrowing the gaps in median family income and home ownership have been erased and are wider now than then. During the same period, black adults have fallen further behind in college degrees, as compared to whites. Blacks have gained ground in the percentage of those with high school degrees and have cut the gap with whites in poverty levels. Still, the difference in the percent of black and white residents living in poverty remains high – 16 percentage points. Latinos, whose population has surged in the U.S. with immigration, have fallen further and further behind their white counterparts in most economic and educational areas. The gaps have steadily grown wider between 1960 and 2010 for median family income and college graduation rates. Gaps in homeownership and high school degrees are higher today then they were 50 years ago. Only the gaps in poverty rates have narrowed since the 1960s and 1970s. Among more positive trends, 82 percent of black adults had graduated from high school in 2010, compared to 20 percent in 1960. Latinos have also improved high school graduation rates through the decades, but still lag badly in 2010 at 62 percent, compared to 91 percent for white adults. Poverty, income and education gaps in the U.S. parallel other important disparities outlined in one critical measure of health after another. Blacks, for example, experience significantly higher rates of infant mortality, and both blacks and Hispanics experience higher death rates from diseases such as diabetes. “Those disparities are real,” said Amitabh Chandra, director of health policy research at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. “Anybody who says, ‘Well, these disparities don’t exist,’ is living in denial.” There may be no more telling statistic about racial and ethnic health disparities that the rate of infant mortality – the death of a baby in the first year of life. It is a number often cited to separate developed nations from developing ones, and it is studied extensively because it is seen by many experts as a key measure of overall health. The infant mortality rate in the U.S. has been on a steady decline since 1958. Even so, black babies die at a rate much higher than white babies, 11 deaths for every 1,000 births compared to 5 deaths for every 1,000 births, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “I find that deeply concerning,” said Dr. Amal Trivedi, a practicing physician and faculty member at Brown University in Providence, R.I. “You know the rates have improved for both groups, but they’re still sharply unequal, deeply unequal, and we can do better as a society.” The widening of the gaps as measured by census data began in the 1980s and 1990s, well before the last recession, which disproportionately impacted minorities’ wealth and incomes. The stakes in not reducing the gaps are high, analysts and researchers say, as the U.S. moves closer to becoming a majority-minority nation. Whiles whites remained a majority of 63.4 percent in 2011, the census reported that as of July 1 that year 50.4 percent of all residents younger than one year of age were minorities. Two of the nation’s most populous states, California and Texas, are majority-minority, as are New Mexico and Hawaii. I-News explored the social phenomena behind the numbers with community activists and politicians, researchers from liberal and conservative think tanks, educators, church leaders and people in the street. The reasons given for the gaps were myriad and complex. They are rooted in history and intergenerational in nature. Among those cited: Civil rights era policies that provided a boost to minorities in the 1960s and ‘70s, such as affirmative action, have been diminished or dismantled. “For all intents and purposes, affirmative action has been wiped out,” said former Denver Mayor Wellington Webb. “There is no longer a desire to assure that minorities are being placed in jobs.” Affirmative action programs, first envisioned by President John F. Kennedy in 1961 and strengthened and expanded by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1965, have been narrowed or eliminated by U.S. Supreme Court decisions and, in individual states, by legislative action or by voters. Good paying, blue collar manufacturing jobs – once a major path to the middle class – have disappeared by the millions. A study by the Center for Economic Research found that fewer than 1 in 10 black workers nationally had a manufacturing job in 2007, down from 1 in 4 in 1979. Support for K-12 education has diminished in many states. The cost of attending college has skyrocketed. The percentage of single-parent families and the number of births to single mothers has soared among black households, exacerbating the gaps, and immigration and teen-age births in the Latino population have also led to widening disparities, experts said. The rise of the single-parent family has created ongoing economic disparity and impacts general prosperity, said Alan Berube, senior fellow and research director for the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program. “In part, it’s about how many adults you have and the income generating power these different households have,” he said. The disproportionate incarceration of minority males contributes to a range of social problems, including the single parent family, said Denver Mayor Michael Hancock and others. The family structure has “disintegrated in a sense,” Hancock said. “That challenge is real.” Nationally, one of every 33 black men and one of every 83 Latino men were behind bars in 2010, according to an analysis of Bureau of Justice reports, compared to one in 150 white men. Former Colorado U.S. Sen. Hank Brown, and others, said the creation of welfare and other government subsidies led to lasting inequities. “What we’ve done in America is design a system that rewards people for not working and locks them into poverty,” Brown said. “It’s a tragedy of the first order.” The I-News analysis found regional differences in how the gaps have changed during the decades. Many Southern states have gone from having the largest economic and education gaps between white and black residents in 1970 to some of the smallest in 2010. Nineteen states have narrowed the gaps between median family incomes between 1970 and 2010. Nine of those states are in the South. Blacks have narrowed the poverty gap in 11 of the 12 Southern states, as defined by the Census Bureau. Four of the 10 states that have narrowed home ownership rates between whites and black are in the South. Three southern states – Tennessee, Kentucky and West Virginia – are among the five states with the lowest gaps for black and white adults with college degrees. UCLA’s Orfield said most civil rights laws were actively aimed at the South during the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. “We changed the South,” Orfield said. “The South was an apartheid system. We really did break it up quite dramatically from the middle of the 1960s to the early 1970s. It was huge, huge social change that very few Americans understand.” Simultaneously, the South went through a period of rapid economic growth that elevated everyone’s status. During those same decades, the gaps in many of the Midwest states went in the opposite direction – from some of the narrowest in the U.S. to some of the widest, the I-News analysis found. The income gaps between white and black families in 10 Midwest states have generally steadily widened since 1960 or 1970 to their highest levels in 2010. For seven of the 10 states, the income gap narrowed during the Civil Rights era, but has been widening ever since. By 2010, four Midwest states – Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin and Nebraska – had four of the five largest income gaps in the U.S. between white and black families. Former Denver Mayor Webb said that partly reflects the severe downturn in manufacturing jobs in many Midwest states and their metro areas. UCLA’s Orfield said the demographics of many Midwest states have changed dramatically since 1970. “Minnesota was a great leader in civil rights, in part, because it had a very small problem,” said Orfield who grew up in the Minneapolis area. “It’s now very different and Minneapolis public schools are now overwhelmingly non-white.” Latino gains have been more elusive across the U.S. in education and income. The Census Bureau had self-acknowledged problems with identifying Latinos in 1970 in some regions, and those problems make many state comparisons unreliable before 1980. However, since 1980, the income gaps have steadily widened in all but five states and the gaps in college degrees have grown larger in all but one state. Latino homeownership rates narrowed in only 10 of the 50 states between 1980 and 2010. “Essentially you are looking at a somewhat different population today than you were in 1980,” said Berube. “Much of that growth is among Mexican immigrants, many of whom come to the United States to work in low-skill jobs.” Orfield said many Latinos missed out on the gains by blacks during the civil rights era because they did not become a political force in the U.S. nationally until the 1980s. By that time, the nation had begun to pull back on affirmative action and other policies, he said. “Latinos were left on their own,” Orfield said. “The lack of having any sort of civil rights policy is beginning to really devastate those communities economically and socially.” Given the ever changing arc of national politics during the decades covered by the analysis, the disparities aren’t “any kind of big surprise,” Orfield said. “It is quite clear there was an intentionality both about the narrowing of the gap and the growing of the gap.” -