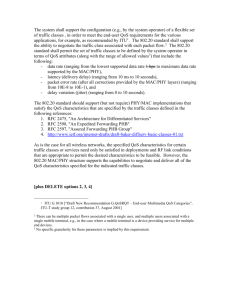

New ECC Report Style

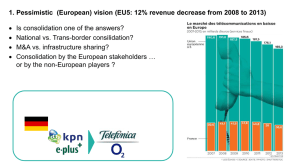

advertisement