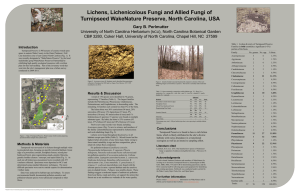

TurnipseedManagementPlan.2010.03.05

advertisement