Glue ear and grommets

Middle ear infections (acute otitis media) in children are common. They often begin in the first year, and most children have had one before the age of five.

The main symptom is ear pain, with a bulging eardrum. The treatment is pain relief and usually a course of an antibiotic. It is important that the whole course is completed, even though the pain has subsided.

Some children get many infections in a year, which is distressing for the child and disruptive for the family. It can take weeks for the infection to completely clear.

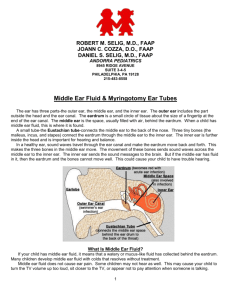

However, children’s Eustachian tubes are not fully mature and this may be delayed, leading to changes in the middle ear which can result in the persistence of fluid or thicker ‘glue’ – then called otitis media with effusion (OME) or ‘glue ear’.

Fluid or glue in both ears can result in hearing loss as long as it persists.

Hearing loss can go unnoticed for months or years, but is often detected on a screening test at day care or school. When OME with hearing loss, persists in both ears, after three months the child has significant disability in regards to hearing at school, and it may account for naughty or frustrated behaviour. At this point, ventilation tubes (grommets) are usually recommended.

The operation of inserting tubes or grommets is done under a brief general anaesthetic, usually in a day surgery centre. Some children also require the removal of the adenoids.

The fluid or glue is suctioned out of the middle ear through a small incision in the eardrum. The tubes are a small device inserted into the incision. Quite simply, they take over the function of the Eustachian tube, and the ventilation from the tubes makes the middle ear dry.

The most commo nly used tubes are a ‘collar button’ shape, with an inner diameter of about 1mm. The tube is usually placed at the front of the eardrum, and it slowly moves around to the back when it becomes a crust and then leaves the drum, which heals behind it. This takes about a year. About 70% of children requiring tubes have a normal middle ear afterwards. In 30%, a further set is required, and in about

15%, three or more times. This does not mean the first tubes were ineffective, but that the child has been slower to outgrow the problem.

There are common misconceptions about ventilation tubes.

It was initially feared that swimming would allow water and infection to enter the middle ear through the tubes, but trials have shown that most children can swim in a clean pool and seawater without a problem. Therefore the earplugs and bathing caps for swimming that were a routine for so long are not required. However, soapy bathwater can pass through the tubes. So putting the head under the bathwater in inadvisable. For hairwashing, use the child’s fingers to bloc the ears – it’s as effective as ear plugs.

By Jeremy Hornibrook, ear, nose and throat specialist at Christchurch Hospital and in private practice at

St George’s Hospital and Southern Cross Hospital, Christchurch.

This article is a short version of “Otitis media and Ventilation Tubes” published in New Zealand Practice

Nurse, August 1995.