Full Text (Final Version , 248kb)

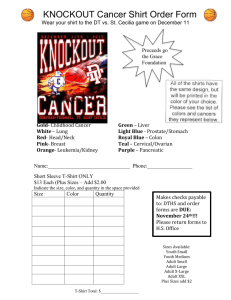

advertisement