facts 2

advertisement

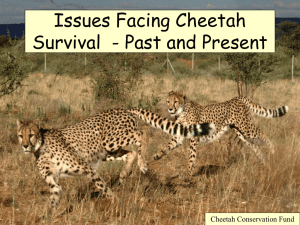

Family: Felidae Genus: Acinonyx Species: Jubatus Description Height: 30+ inches at shoulder Weight: 69-140 lbs. Body length: 4 feet Tail length: 28.5 inches The world's fastest land mammal, the cheetah, is the most unique and specialized member of the cat family and can reach speeds of 70 mph. Unlike other cats, the cheetah has a leaner body, longer legs, and has been referred to as the "greyhound" of the cats. It is not an aggressive animal, using flight versus fight. With its weak jaws and small teeth--the price it paid for speed, it cannot fight larger predators to protect its kills or young. The cheetah is often mistaken for a leopard. Its distinguishing marks are the long teardrop-shaped lines on each side of the nose from the corner of its eyes to its mouth. The cheetah's coat is tan, or buff colored, with black spots measuring from 78 to 1.85 inches across. There are no spots on its white belly, and the tail has spots that merge to form four to six dark rings at the end. The tail usually ends in a bushy white tuft. Male cheetahs are slightly larger than females and have a slightly bigger head, but it is difficult to tell males and females apart by appearance alone. The fur of newborn cubs is dark and the spots are blended together and barely visible. During the first few weeks of life, a thick yellowish-gray coat, called a mantle, grows along the cub's back. The dark color helps the cub to blend into the shadows, and the mantle is thought to have several purposes, including acting as a thermostatic umbrella against rain and the sun, and as a camouflage imitating the dry dead grass. The mantle is also thought to be a mimicry defense, causing the cub to resemble a ratel, or honey badger, which is a very vicious small predator that is left alone by most other predators. The mantle begins to disappear at about three months old, but the last traces of it, in the form of a small mane, are still present at over two years of age. The cheetah is aerodynamically built for speed and can accelerate from zero to 40 mph in three strides and to full speed of 70 mph in seconds. As the cheetah runs, only one foot at a time touches the ground. There are two points, in its 20 to 25 foot (7-8 metres) stride when no feet touch the ground, as they are fully extended and then totally doubled up. Nearing full speed, the cheetah is running at about 3 strides per second. The cheetah's respiratory rate climbs from 60 to 150 breaths per minute during a highspeed chase and can run only 400 to 600 yards before it is exhausted; at this time it is extremely vulnerable to other predators, which may not only steal its prey, but attack it as well. The cheetah is specialized for speed through many adaptations: It is endowed with a powerful heart, oversized liver, and large, strong arteries. It has a small head, flat face, reduced muzzle length allowing the large eyes to be positioned for maximum binocular vision, enlarged nostrils, and extensive air-filled sinuses. Its body is narrow, lightweight with long, slender feet and legs, and specialized muscles, which act simultaneously for high acceleration, allowing greater swing to the limbs. Its hip and shoulder girdles swivel on a flexible spine that curves up and down, as the limbs are alternately bunched up and then extended when running, giving greater reach to the legs. The cheetah's long and muscular tail acts as a stabilizer or rudder for balance to counteract its body weight, preventing it from rolling over and spinning out in quick, fast turns during a high-speed chase. The cheetah is the only cat with short, blunt semi-retractable claws that help grip the ground like cleats for traction when running. Their paws are less rounded than the other cats, and their pads are hard, similar to tire treads, to help them in fast, sharp turns. Distribution It has been estimated that in 1900, more than 100,000 cheetahs were found in at least 44 countries throughout Africa and Asia. Today the species is extinct from +20 countries and about 10,000 animals remain, found mostly in small-pocketed populations in 23 to 26 countries in Africa and -100 in Iran. The cheetah is classified as an endangered species, and listed in Appendix I (which includes species that are most threatened) of the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Prior to the 20th century, cheetahs were widely distributed throughout Africa and Asia, and were originally found in all suitable habitats from the Cape of Good Hope to the Mediterranean, throughout the Arabian Peninsula and the Middle East, from Israel to India, and through the southern provinces of the former Soviet Union. Today, the Asian cheetah is nearly extinct, due to a decline of available habitat and prey. The species was declared extinct in India in 1952, and the last reported cheetah was seen in Israel in 1956. Today, the only confirmed reports of the Asian cheetah comes from Iran, where less than 100 occur in small isolated populations. Free-ranging cheetahs still inhabit a broad section of Africa, including areas of North Africa, the Sahel, East Africa, and southern Africa. Viable populations may be found in less than half of the countries where cheetahs still exist. These declining populations mean that those cheetah which do survive, come from a smaller, less diverse gene pool. Populations continue to decline from loss of habitat, decline of prey species, and conflict with livestock farming. Throughout Africa, cheetahs are not doing well in protected wildlife reserves due to increased competition from other larger predators, such as lion and hyenas, and most protected areas are unable to maintain viable cheetah populations. Therefore, a large percentage of the remaining cheetah populations are outside of protected reserves, placing them in greater conflict with humans. There are now only two remaining population strongholds: Namibia/Botswana in southern Africa, and Kenya/Tanzania in East Africa. The cheetah's greatest hope for survival lies in the relatively pristine countryside of Namibia, which is home to the world's largest remaining population of cheetah. However, even in Namibia, the cheetah's numbers drastically declined by half in the 80s, leaving an estimated population of less than 2,500 animals. At the beginning of the 1990s, when CCF began its work with the farming community, a gradual change has occurred within Namibia, and over the last couple of years the population has stabilized or slightly increased. CCF's research has shown that farmers have more tolerance for cheetahs and are killing less, and those that are being killed are linked to livestock losses, or that they are calling CCF to help them. Habits The cheetah is generally considered to be an animal of open country and grass lands. This impression is probably due to the ease of sighting the cheetah in the shorter grass. However, cheetahs use a wider variety of habitats, and are found often in dense vegetation and even mountainous terrain. Since cheetahs rely on sight for hunting, they are diurnal: more active in the day than night. In warm weather, they move around mostly during the early morning and late in the afternoon when the temperatures are cooler. Cheetahs prey on a variety of species from rabbits to small antelope, and the young of larger antelope. Their hunting technique is to stalk as close as possible to the prey, burst into full speed, tripping the prey with a front paw and, as the prey falls, biting it by the throat in a strangulation hold. Cheetahs are more social in their behaviors than once thought. They will live singly or in small groups. Female cheetahs are sexually mature at 20 to 24 months. The mating period lasts from one day up to a week. The female's gestation period is 90 to 95 days, after which she will give birth to a litter of up to 6 cubs. She will find a quiet, hidden spot in the tall grass, under a low tree, in thick underbrush, or in a clump of rock. Cheetah cubs weigh between 9 to 15 ounces when born. Although cheetah cubs are blind and completely helpless at birth, they develop rapidly. At 4 to 10 days of age, their eyes open, and they begin to crawl around the nest area; at 3 weeks their teeth break through their gums. Due to the possibilities of predation from a variety of predators, the female moves her cubs from den to den every few days. For the first 6 weeks, the female has to leave the cubs alone most of the time, in order to hunt. Also, she may have to travel fairly long distances in search of food. During this time, cub mortality is as high as 90 percent in the wild, due to predation. The cubs begin to follow their mother at 6 weeks old, and begin to eat meat from her kills. From this time onward, mother and cubs remain inseparable until weaning age. The cubs grow rapidly and are half of their adult size at 6 months old; at 8 months old, they have lost the last of their deciduous teeth. About this time, the cubs begin to make clumsy attempts at stalking and catching. Much of the learning process takes the form of play behavior. The cubs stalk, chase and wrestle with each other and even chase prey that they know they cannot catch, or prey that is too large. The cubs learn to hunt many different species, including guinea fowl, francolins, springhares, and small antelope. They still are not very adept hunters at the time they separate from their mothers. The female leaves her cubs when they are between 16 to 18 months old to rebreed, starting the cycle over again. The cubs stay together for several more months, usually until the female cubs reach sexual maturity. At this time, the male cubs are chased away by dominant breeding males. Male cubs stay together for the rest of their lives, forming a coalition. Male coalition is beneficial in helping to acquire and hold territories against rival male cheetahs. Males become reproductively active between 2 and 3 years of age. Cheetahs & Humans The cheetah's long association with humans dates back to the Sumerians, about 3,000 BC, where a leashed cheetah, with a hood on its head, is depicted on an official seal. In early Lower Egypt, it was known as the MAFDET cat-goddess and was revered as a symbol of royalty. Tame cheetahs were kept as close companions to pharaohs, as a symbolic protection to the throne. Many statues and paintings of cheetahs have been found in royal tombs, and it was believed that the cheetah would quickly carry away the pharaoh's spirit to the after life. By the 18th and 19th centuries, paintings indicated that the cheetah rivaled dogs in popularity as hunting companions. The best records of cheetahs having been kept by royalty, from Europe to China, are from the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries. Hunting with cheetahs was not to obtain food, which royalty did not need, but for the challenge of sport. This sport is known as coursing. Adult wild cheetahs were caught, as they already had well developed hunting skills and were tamed and trained within a few weeks. The cheetahs were equipped with a hood, so they could not see the game they were to hunt, and were taken near the prey either on a leash, a cart, or the back of a horse, sitting on a pillow behind the rider. The hood was then removed and the cheetah dashed after the prey, catching it, after which the trainer would reward it with a piece of meat, and then take the cheetah back to the stable where it was kept. Many emperors kept hundreds of cheetahs, at any given time, in their stables. With this great number of cheetahs in captivity, it was recorded only once, by Emperor Jahangir, the son Akbar the Great, an Indian Mogul in the 16th century, that a litter of cubs was born. During his 49-year reign, Akbar the Great had over 9,000 cheetahs, in total, which were called Khasa or the "Imperial Cheetahs," and he kept detailed records on them. All of the cheetahs kept as "hunting leopards" were taken from the wild. Because of this continuous drain on the world populations, the numbers of cheetahs declined throughout Asia. In the early 1900's, India and Iran began to import cheetahs from Africa for hunting purposes. Other Survival Challenges Molecular genetic studies on free-ranging and captive cheetahs have shown that the species lacks genetic variation, probably due to past inbreeding, as long as ten thousand years ago. The consequences of such genetic uniformity have led to reproductive abnormalities, high infant mortality, and greater susceptibility to disease, causing the species to be less adaptable and more vulnerable to ecological and environmental changes. Unfortunately, captive breeding efforts have not proven to be meaningful to the cheetah's hope for survival. The similar experiences of the world's zoos have reaffirmed the traditional difficulties of breeding cheetahs in captivity. Despite the capturing, rearing, and public display of cheetahs for thousands of years, the next reproductive success, after Akbar the Great son's recorded birth of one litter in the 16th century, occurred only in 1956 at the Philadelphia Zoo. Unlike the other 'big cats', which breed readily in captivity, the captive population of cheetahs is not self-sustaining and, thus, is maintained through the import of wild-caught animals, a practice which goes against the goals of today's' zoological institutions. Although reproduction has occurred at many facilities in the world, only a very small percentage of cheetahs have ever reproduced and cub mortality is high. In the absence of further importations of wild-caught animals, the size of the captive population can be expected to decline, a trend, which coupled with the continuing decline of the wild population, leaves the species extremely vulnerable. Conservation Efforts We founded the Cheetah Conservation Fund (CCF) in 1990 to directly confront the above issues and to implement techniques for cheetah conservation in their natural habitat. The CCF is the only fully established, on-site, international conservation effort for the wild cheetah. A permanent base for this long-term effort was established in 1991 in Namibia, Africa-- home to the largest remaining, viable, population of cheetah. CCF's primary mission is to focus on conservatory and management strategies outside of protected parks and reserves. It conducts research, disseminates information, and implements conservation management techniques that will lead to the long-term survival of freeranging cheetah. The project is directed by Laurie Marker. The over-all objective of CCF is to secure the survival of free-ranging cheetahs in suitable African habitats. The CCF's long-term program focuses on cheetah research and conservation education; as well as livestock and wildlife management, education, and training. In Namibia, programs are being developed that can be adapted for use in other cheetah range countries. The goal is to develop workable strategies for promoting sustainable cheetah populations, a goal which, in the end, is largely dependant on the willingness and the capacity of individuals and local communities where the cheetahs live. As a part of the long-term program, conservation efforts are being developed through the knowledge gained from the collection of base-line data including: the distribution and movements of cheetahs through the Namibian farmlands; the problems leading to the continued elimination of the cheetah; the assessment of the over-all health of the free-ranging cheetah population; the development of livestock farm management practices to reduce conflict with cheetahs the development of livestock/wildlife management and education to sustain a balanced ecosystem that supports wildlife, and cheetah; and the adaptation of successful programs to other countries where cheetah still exist or might be reintroduced. The knowledge gained from this program will reveal the necessary information to employ strategies for the long-term survival of the species throughout its range and contribute to maintenance of captive cheetahs, which are 99% from Namibian stock.