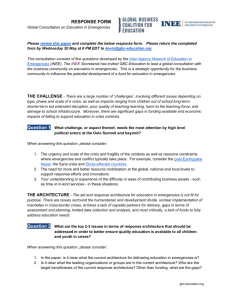

Day One - s3.amazonaws.com

advertisement