past, present and future - The University of Sheffield

advertisement

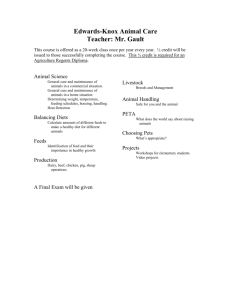

Humans, livestock and their landscape: past, present and future Jessop West Exhibition Centre, 5th May 2015 Organised by: Umberto Albarella & Angelos Hadjikoumis LIST OF ABSTRACTS (IN DELIVERY ORDER) Hector Orengo (Dept. of Archaeology, University of Sheffield): The pastoral landscapes of northeastern Spain: long-term multidisciplinary approaches and current research perspectives The study of pastoral landscapes is currently characterised by multidisciplinary approaches, which include archaeological survey and excavation, geoarchaeology, palaeoenvironmental analyses and GIS. Pastoralism has been recognised as one of the earliest and most important causes of human-related environmental change. Most importantly, these pastoral-related environmental impacts are determined by specific socio-cultural settings and historical dynamics. Through the study of landscapes, therefore, important insights can be gained on human-animal relationships. This papers aims at providing an overview of current research on pastoral landscapes in north-eastern Spain. It will focus on the long-term socio-cultural dynamics that generated specific human-animal relationships and how these can be investigated using landscape-based multidisciplinary approaches. Bob McKay & John Miller (School of English, University of Sheffield): Literary pigs Part I: ‘Many’s the Rum-tempered Pig I’ve Knowed’: Thomas Hardy’s Porcine Plots (Miller) Thomas Hardy’s third novel A Pair of Blue Eyes (1873) contains an extended scene of reminiscences in which the ‘pig-killer’ Robert Lickpan expands on his reflection that ‘Many's the rum-tempered pig I've knowed’. Among the curious beasts of his professional acquaintance, Lickpan numbers an easily tricked ‘deaf and dumb pig’ and another, ‘never a hopeful pig’, who eventually ‘went out of his mind’. Lickpan’s folksy anecdotes encapsulate a key tension in Hardy’s oeuvre. Animals are a vital resource in the rural economies so intimately associated with Hardy. At the same time, they are individuated, sentient, wilful and, frequently, resourceful. This short paper examines the occasions on which Hardy’s pigs drive his plots as characters in their own right, rather than appearing merely as part of the agricultural backdrop. Part II: ‘Once In A While Something Slips’ (McKay) This short literary history of the porcine post-war develops the theme of pigs wresting control of human plots. In ‘Death of a Pig’ (1948), his essay-memoir of rural Maine, E.B. White documents how a pig that he is raising for slaughter unexpectedly dies a death all of his own; this compels White to imagine anew not just what he calls ‘the tragedy enacted on most farms with perfect fidelity to the original script’ but the life-story-defining event of mortality itself. In Roald Dahl’s macabre story ‘Pig’ (1960), we discover the speed with which pretensions to moral goodness can be distracted by desire as the central character receives a sharp lesson in human rapaciousness on a slaughterhouse tour. In Patricia Highsmith’s ‘In the Dead of Truffle Season’, from her wickedly satirical Animal Lover’s Book of Beastly Murder (1975), a French truffling boar savours his just rewards shortly after his greedy owner gets his just desserts. These porcine stories of life and death give a derisory snort to the self-absorption, pretension, naivety, ignorance, wilfulness, and self-interest that are properly human. Paul Halstead (Dept. of Archaeology, University of Sheffield): Livestock and landscapes in the high Pindos Mountains of NW Greece: past, present and future The Pindos of NW Greece, like other high mountains of the Mediterranean basin, is well known as the summer home of transhumant or nomadic pastoral groups (in this case, the Vlachs and Sarakatsani), that overwintered their goats, horses and especially sheep in adjacent or distant lowlands. The Pindos, again like other Mediterranean mountains, was until recently also occupied year-round by numerous communities of mixed crop-livestock farmers. Which of these contrasting montane lifeways is more ancient is the subject of debate, not least because Mediterranean historians and archaeologists have tended to focus on the more familiar and accessible lowlands of the region. Pindos pastoralists and mixed farmers alike created distinctive cultural landscapes that, in large measure, reflect the contrasting demands and effects of largescale seasonal and small-scale year-round animal husbandry. Both forms of cultural landscape are now rapidly being obscured by progressive reafforestation. This presentation will illustrate some of the traces of these past cultural landscapes that can still be found within the new forests, will consider their significance for improving understanding of the history of these contrasting montane lifeways, and will optimistically suggest some tentative implications for the future development of the high Pindos. Sally Rodgers & Sarah Wild (Heeley City Farm, Sheffield): Rare, Heritage and Native Breeds at Heeley City Farm Heeley City Farm is a charity which seeks to engage all members of the community with farming and its various aspects, whilst educating about the ethical and environmental issues involved. Raising rare breeds fits in with our philosophy as they often have less of a footprint than their more commercial counterparts and we are also helping to preserve Britain’s native breeds. Through trial and error we have discovered which breeds work well for us and developed a market to make producing their meat worthwhile as well as finding some innovative ways to promote the breeds and make a little extra money for the farm. Angelos Hadjikoumis (Dept. of Archaeology, University of Sheffield) The Iberian pig is one of few traditional European breeds that have remained unaffected by the introgression of Asian pig breeds. This altered the genetic and consequently phenotypic, behavioural and reproductive characteristics of most modern European breeds. Despite a common overall morphology and behaviour, the Iberian is a diverse breed consisted of several ‘lineages’ with minor differences. In this presentation, the breed’s morphological and behavioural characteristics are presented in the context of free- or semi-free-range systems in southwest Iberia. Only when viewed in the environment in which it has been ‘moulded’ and is still managed in, the Iberian pig is appreciated in its uniqueness. The dehesa, in which the Iberian pig is managed, is a unique agrosilvopastoral system (i.e. crop cultivation + woodland management + animal husbandry) geared to enhance the productivity and sustainability of pig husbandry. Beyond the presentation of the Iberian pig, the environment in which it is managed and the animal husbandry practices related to it, this presentation stresses the importance of preserving the genetic, behavioural and cultural heritage that endures in such traditional animal husbandry systems. Jo Booth (Whirlow Hall Farm, Sheffield): Whirlow Hall Farm Trust – a classroom in the countryside The presentation will: detail our current educational work linking children and young people with animals, farming and the environment; outline the site’s 2000 year farming history; and consider opportunities for future development in recreating our Iron Age farm. We will also include examples of the impact we achieve in raising awareness of where food comes from, alongside development of vocational, personal and social skills. Umberto Albarella (Dept. of Archaeology, University of Sheffield): Born to be free: pastoralism in the Sardinian upland Often perceived as a classic biogeography ‘laboratory’ in the middle of the Mediterranean, Sardinia has also been characterised for most of its history by a peculiar form of pastoralism. Low densities of human population, accompanied by a strong sense of insularity, have contributed to the creation of a natural and cultural landscape that is unique. Pastoralism has been the main form of subsistence - in frequent competition and occasional cooperation with farming - in particular in central Sardinia. In this area people have traditionally lived in very close contact with livestock – sheep, goats, cattle and pigs. Communal lands, high mobility, free-range keeping of animals, and the development of sturdy and undemanding, but also lowly productive, animal breeds are typical characteristics of husbandry strategies in central Sardinia. This lifestyle has, however, been under threat for centuries and today is on the verge of vanishing. I will argue that that the potential disappearance of the traditional forms of herding in Sardinia will represent a loss of a precious cultural heritage as well as a threat to both the welfare of the animals and their environments. Alasdair Cochrane (Dept. Politics, University of Sheffield): Born in Chains? The Ethics of Animal Domestication How should we conceive of the domestication of animals from an ethical perspective? Was the process, some 10,000 years ago, in which humans separated, tamed and bred certain animals for specific traits a great leap forward for humanity that we should celebrate, or the terrible first step in a long catalogue of domination and oppression? And how should we deal with the results of that process here in the current world? Very little attention has been paid to these questions in animal ethics – or indeed in other disciplines. Nonetheless, this talk identifies and critically evaluates four positions that can be found in the literature. First is the claim that domestication was and is wrongful because it turns natural entities into man-made ‘artefacts’. Second, is the competing idea that the process of animal domestication was benign because it resulted in important mutual benefits. Third is the abolitionist claim that domestication is wrongful and must be eradicated because it necessarily turns animals into ‘slaves’. And finally is the more recent claim that domesticated animals should not be eradicated, but are instead owed certain special obligations as a result of their dependency. The talk finds all of these positions to be problematic. It argues that we have no duty to eradicate domestication or the captivity of domesticated animals per se, but that we do have a duty to eradicate the suffering and deaths which contemporary forms of domestication entail.