Electronic Supplementary Material Intralocus sexual conflict over

advertisement

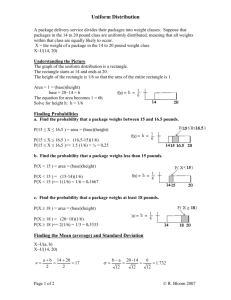

Electronic Supplementary Material Intralocus sexual conflict over height Table S1. Descriptive statistics (mean ± s.d.) of the respondents and siblings from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (only sibling pairs where the age difference was less than ten years were included). Respondent Male Female (N=1,665) (N=1,857) Height (cm) 179.2 ± 6.5 164.2 ± 6.1 Birth year 1938.8 ± 0.5 1938.9 ± 0.4 Number of 2.5 ± 1.5 2.8 ± 1.7 children Selected Sibling Male Female (N=1,669) (N=1,853) 179.0 ± 6.3 164.0 ± 6.1 1939.6 ± 5.2 1939.7 ± 5.2 2.5 ± 1.6 2.7 ± 1.7 Table S2. Pearson correlation coefficients describing the association between sibling heights. (all p < .0001) Pearson r .475 .406 .449 Heritability (h2)a 0.950 0.812 0.898 Brothers (N=808) Sisters (N=996) Opposite-sex siblings (N=1,718) a To obtain h2, the correlation coefficient r between heights of full siblings is multiplied by 2. This calculation, however, includes the effect of the shared environment and thus overestimates h2. These correlation coefficients are reasonably close to what is expected on the basis of the h2 range reported for height in Western populations [11, see main text]. Table S3. Poisson regression parameter estimates (± s.e.) and p-values (based on Z-value) for the effect of height, height2, birth year (centered) and birth year2 on reproductive success for the male (N = 1,669) and female (N = 1,853) siblings of the main respondents. Male siblings Female siblings Parameter estimate (± s.e.) p-value Parameter estimate (± s.e.) Intercept -18.48 (± 8.94) .039 2.25 (± 0.38) Birth year -0.030 (± 0.003) <.001 -0.039 (± 0.003) a Birth -1.32*10-3 (± 5.25*10-4) year2 Height 0.22 (± 0.10) .028 -7.63*10-3 (± 2.33*10-3) b Height 2 -6.20*10-4 (± 2.80*10-4) .027 a Squared term of birth year not significant for males (p =.604) b Squared term of height not significant for females (p = .563) p-value .013 <.001 .012 .001 Figure S1. The effect of the (a) male and (b) female height (in bins of 2.5 cm) on the number of children ever born for the selected siblings of the main respondents (see main text). For men, bins below 165 cm and above 192.5 cm, and for women bins below 150 cm and above 177.5 cm were collapsed. A significant curvilinear effect was found for men (with the optimum at a height of 177 cm) and a negative effect for women (Table S3). Table S4. Mixed model Poisson parameter estimates (± s.e.) and p-values (based on Z-value) for the effect of the average height (standardized) and height2 of the sibling pair, sex of the individual and their interactions on the number of children (N = 7,044). A random intercept was included for sibling pair. Intercept Sex (ref. cat=male) Pair height Pair height 2 Sex * Pair height Sex * Pair height2 Parameter estimates (± s.e.) 0.93 (± 0.014) 0.054 (± 0.019) -0.025 (± 0.014) -0.035 (± 0.011) -0.035 (± 0.018) 0.046 (± 0.015) Random effect Sibling pair Parameter estimates (± s.d.) 0.025 (± 0.16) p-value <.001 .004 .066 .002 .052 .003 Figure S2. The effect of the average height of the sibling pair (average over heights standardised per sex) on (a) the number of children (mean ± s.e.) through the brother (closed circle and solid line) and the sister (open circle and dashed line; predictions based on estimates Table S4) and (b) the difference in reproductive success (pooled s.e. from (a)) between sisters and brothers (minus the overall average difference in number of children between the sexes – see text). Height was divided in bins of 0.5. Bins ≤-2 and ≥2 were pooled. Table S5. Mixed model Poisson parameter estimates (± s.e.) and p-values (based on Z-value) for the effect of the average height (standardized) and height2 of the sibling pair, sex of the individual and their interactions on the number of children in opposite-sexa sibling pairs (N = 3,346). A random intercept was included for sibling pair. Intercept Sex (ref. cat=male) Pair height Pair height 2 Sex * Pair height Sex * Pair height2 Parameter estimates (± s.e.) 0.95 (± 0.019) 0.023 (± 0.026) -0.029 (± 0.019) -0.048 (± 0.016) -0.021 (± 0.025) 0.061 (± 0.021) p-value <.001 .37 .13 .003 .41 .004 Random effect Parameter estimates (± s.d.) Sibling pair 0.024 (± 0.15) a Estimates were very similar when including same-sex sibling pairs (see main text, Table 1, and Table S4). No significant three-way interaction was found between sex and type of sibling pair (same-sex versus opposite sex) and the average height of the sibling pair (p = .41) nor the squared average height (p = .31). Thus, the effect of height was not specific to opposite-sex sibling pairs, nor could they be attributed to the inclusion of same-sex sibling pairs. Table S6. Mixed model Poisson parameter estimates (± s.e.) and p-values (based on Z-value) for the effect of the height (standardized) and height2 of both individuals from the sibling pair, sex of the individual and their interactions on the number of children (N = 7,044). A random intercept was included for sibling pair. Intercept Sex (ref. cat=male) Height Height 2 Sex * Height Sex * Height2 Parameter estimates (± s.e.) 0.94 (± 0.014) 0.045 (± 0.018) -0.019 (± 0.012) -0.037 (± 0.008) -0.035 (± 0.016) 0.043 (± 0.011) Random effect Sibling pair Parameter estimates (± s.d.) 0.024 (± 0.16) p-value <.001 .014 .105 <.001 .023 <.001 Table S7. Mixed model Poisson parameter estimates (± s.e.) and p-values (based on Z-value) for the effect of an individual’s height (standardized) and height2, sibling sex, and their interactions on the number of children by the siblinga, while controlling for the sex of the individual (N = 7,044). Because we had data available from 3,522 pairs of siblings, a random intercept was included for sibling pair (see main text). Intercept Sex (ref. cat=male) Sibling sex (ref. cat=male) Height Height 2 Sex sibling * Height Sex sibling * Height2 Parameter estimates (± s.e.) 0.82 (± 0.039) 0.021 (± 0.015) 0.064 (± 0.018) -0.0067 (± 0.025) -0.012 (± 0.017) -0.012 (± 0.015) 0.024 (± 0.010) p-value <.001 .160 <.001 .791 .019 .454 .017 Random effect Parameter estimates (± s.d.) Sibling pair 0.025 (± 0.16) a Rather than analysing the effect of height on reproductive success within sibling pairs, a different approach to examine intralocus sexual conflict over height would be to examine what the effect of an individual’s height is on the reproductive success of the sibling of that individual. This approach is more similar to that of [7, see main text], who showed that physically and hormonally masculine men and women rated their brothers as more attractive than their sisters. In line with this study, we predict that the height of an individual predicts the reproductive success of a sister differently than the reproductive success of a brother. Thus, a significant effect of an interaction between an individual’s height and the sex of the sibling on the reproductive of that sibling is expected. Acknowledgements This research used data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS) of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Since 1991, the WLS has been supported principally by the National Institute on Aging (AG-9775 and AG-21079), with additional support from the Vilas Estate Trust, the National Science Foundation, the Spencer Foundation and the Graduate School of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. A public-use file of data from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study is available from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1180 Observatory Drive, Madison, Wisconsin 53706 and at http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/wlsresearch/data/. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors.